![]()

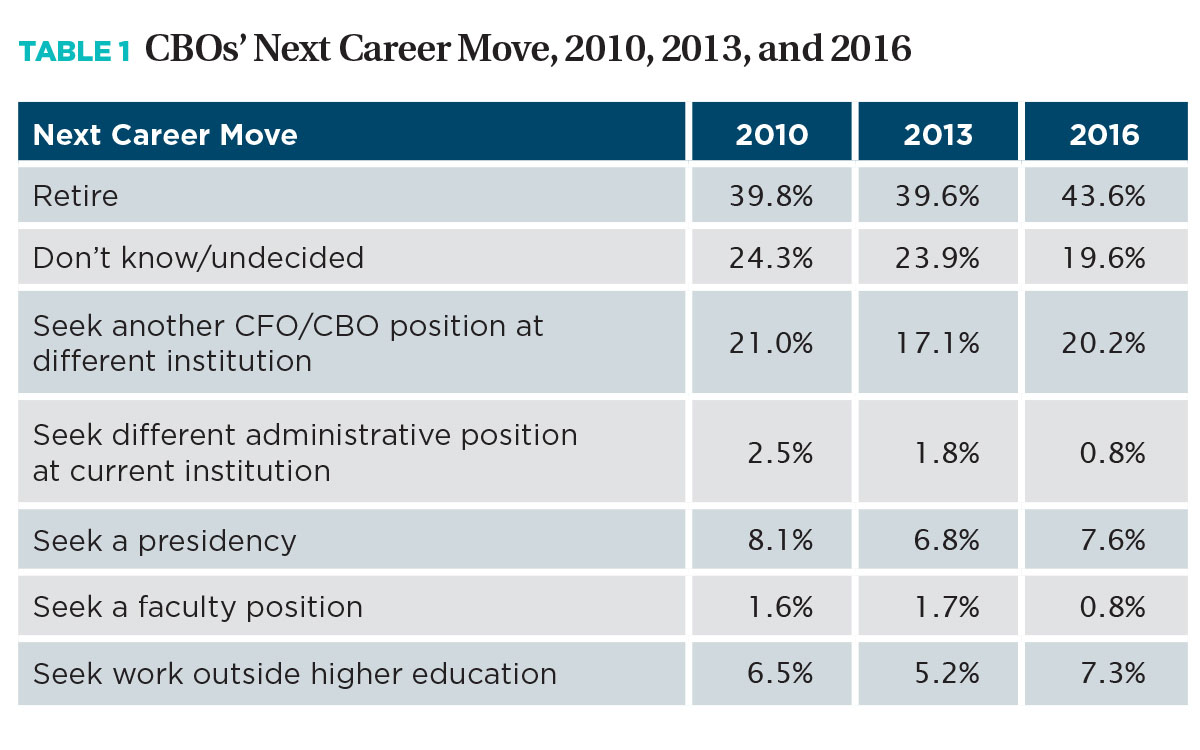

Even more prevalent than in NACUBO’s previous national survey of CBOs in 2013, the 2016 National Profile of Higher Education Chief Business Officers finds a high percentage of CBOs (nearly 44 percent) indicating that their next professional step is retirement. In 2013, that number was 40 percent. Yet, 37 percent of CBOs report that no succession plan is in place for their soon-to-be-open positions. Further, 49 percent believe that there is only an informal succession plan in place at their institutions.

What does this trend mean for the future of higher education institutions? Is the next generation of CBOs waiting in the wings to take the place of retiring CBOs? In her June 2014 white paper Leadership, Diversity, and Succession Planning in Higher Education, C. Ellen Washington, leadership scholar in residence at NC State University, Raleigh, noted that “despite the growing need and interest in succession planning, many institutions are still ill-prepared to handle changes in leadership that may be short-term or long-term placements.”

Interestingly, 20 percent of CBOs indicated that their next expected career move was seeking another CFO/CBO position at a different institution (see Table 1). Very few (only 7.6 percent) plan to seek presidency at a higher education institution in the future. Most cite lack of interest in the work or not having a terminal degree as their reasons.

Profiling the CBO as Change Master

I wanted to learn how the position of CBO is changing,” says Corey S. Bradford, senior vice president of business affairs at Prairie View A&M University, Prairie View, Texas. Bradford served on NACUBO’s CBO Profile Committee and participated in developing the questions and methodology for this year’s survey.

“In my opinion, the position has taken on more of a COO role,” Bradford suggests. “CBOs are more engaged in research, risk management, and other strategic management activities. Duties that presidents used to assume now belong to the CBOs.”

Yet, very few (7.6 percent) plan to seek a presidency in the future. “Many cited lack of a doctorate degree as a barrier to pursuing that role,” Bradford notes, which isn’t the case for him. Bradford earned his Ph.D. in higher education administration from Southern Illinois University Carbondale. “I would be interested in pursuing a presidency in higher education. It’s a goal of mine, and if you’re already working in business affairs and want to pursue a broader leadership role, you’ve got to pursue some type of terminal degree.”

Bradford wasn’t surprised by survey results indicating that many institutions don’t have formal succession plans in place for the chief business officer role. “We have to look at an institution’s hiring pattern,” he says. “Do they [managers] typically hire from outside the institution? Getting some new blood and ideas is often the approach when bringing on a new CBO. If they just want to keep the current operations going as is, they might take the internal route.”

In Bradford’s case, the CBO at his former institution is still there. “If I felt like I was ready for the CBO role, I had to pursue it at another institution,” he notes. However, Prairie View A&M is taking a proactive approach to succession planning with the recent launch of Leadership PVAMU, a professional development program designed specifically to prepare high-performing staff to take on leadership positions in the future. Bradford says of the new initiative, “It is a succession planning tool. We are investing in people so that we can keep good talent at Prairie View.”

Given these trends and lack of formal succession planning, the career path for those desiring future CBO positions seems somewhat uncertain. In a series of interviews with Business Officer magazine, higher education business office professionals at various stages in their careers offered their perspectives on how these trends have shaped their views of the current and future workplace environments at their institutions.

New, and Thinking Ahead

Even as they gain their footing at their institutions, new chief business officers have a unique perspective on succession planning. Often they are not internal hires and may have come from fields outside higher education. For example, now in his third year as vice president of administration and finance at the College of Central Florida, F. Joseph Mazur III didn’t expect to pursue a career in higher education. “I thought that I would be working for a CPA firm or a corporation,” Mazur says.

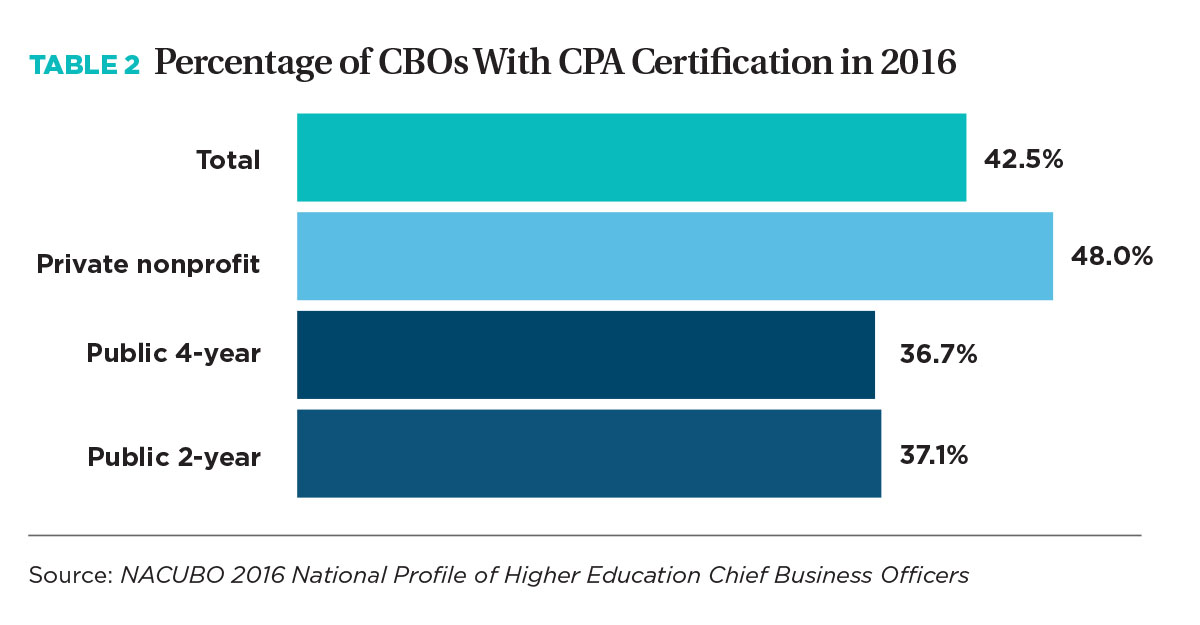

“After my initial hire, I thought this might be a viable career path of working toward a bigger cause of helping the community,” Mazur continues. “I went back to public accounting for a year, but I had more job satisfaction working in higher ed.” Before coming to Central Florida, Mazur most recently served as dean of finance at Indian River State College, Fort Pierce, Fla. He began his tenure there in 2006 and further refined his career goals. “My former boss and I had a great relationship,” Mazur notes. “We discussed succession planning. CBO was ultimately the role that I envisioned myself in, but I knew that I needed to build my resume and experience.” With that in mind, Mazur obtained a master’s degree and the CPA designation, which he says enabled him to bring this additional skill set to Indian River and allowed him to be seen as a trusted adviser. The survey indicates that a small percentage of CBOs have CPA certifications (see Table 2).

When Mazur left Indian River after eight years, he was well prepared to fill the CBO role at Central Florida and felt that the institution and its leadership were a good fit for his next career move. “The previous CBO retired and left the institution in good shape,” he says. “During the interview, the president—who had only been there a year—communicated his principles of management and leadership style, which stressed accountability and transparency. I asked him how he saw my role fitting into the college’s mission, and I felt that we had the same vision for my role and the institution as a whole.”

Dave Duryea, vice president for finance and management at SUNY Cortland, also feels supported in his approach to the CBO role. A retired U.S. Navy rear admiral, Duryea came to the institution just a year ago when he replaced a longtime employee who had passed away. According to Duryea, his predecessor had intended to retire from the position.

“From my perspective, the strength that I brought to an institution where there hasn’t been a lot of turnover in senior leadership was the outside perspective of someone not from a higher ed background who could ask why we’re doing things a certain way,” Duryea explains. “This doesn’t always go over well, but my president is very supportive of my asking those questions.

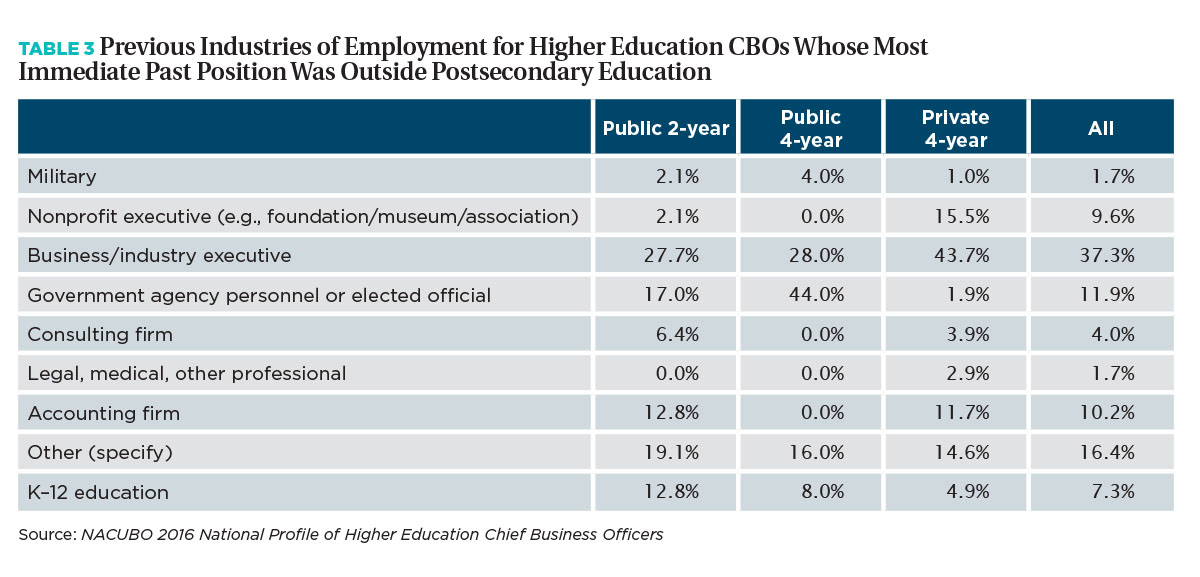

“I was a career military officer, and it was time to do something else,” he continues. “The mission of the military was never about the individual but the nation, and I was looking to join another organization with a greater good mission.” To accomplish this goal, Duryea reached out to a network of family and friends, who were retired or active university presidents, as well as other retired military members in senior leadership positions in higher education. NACUBO’s survey findings reveal that while a small percentage of CBO hires come from a military background, the largest number coming from outside of postsecondary education hail from business and industry fields (see Table 3).

Lessons in Longevity and Leadership

Most chief business officers can’t imagine spending 50 years at the same institution, but Warren Madden wouldn’t have had it any other way. He retired this year after working at Iowa State University, Ames, since 1966, serving as chief business officer since 1984.

“I’ve had the chance to move to other institutions a number of times, but I elected to stay at Iowa State,” Madden says. “I don’t have any regrets about staying this length of time. This institution was the best fit for me professionally and personally. All the presidents I’ve worked with have been amenable to my participating in professional development activities. That’s been part of what kept me going all these years—the opportunity to contribute to the profession on a national level. I’ve been able to balance my campus commitments with external activities, and you have to have an administrator who allows for that.”

Madden is past president of the Central Association of College and University Business Officers. He chaired the business affairs council of the National Association of State Universities and Land-Grant Colleges, and served on the board of directors for the Council of Governmental Relations. In 1993, he received NACUBO’s Distinguished Business Officer Award.

As a manager, he recognized that these kinds of opportunities were also important to his staff, whether they remained at Iowa State or moved on to positions at other institutions. “My type of career path is not going to happen that much in the future,” Madden acknowledges. “For most of the people working for me, I’ve had a role in hiring and promoting. One of the lessons you learn early on is that there are lots of ways to get something done. You have to realize that others may have a slightly different approach than you do, and accept that. I try to hire people who are better at what they do than I am.”

Through years of adapting to the management styles of five different Iowa State presidents, Madden also learned to adapt his own management style to best meet the needs of the current workforce. “People generally say that they like my style of being engaging and accessible and not looking over everyone’s shoulder,” he explains. “However, it’s different today than it was when I first started. I have had to adjust my management style.

“For instance, younger professionals that I hire today want to spend their weekends attending their kids’ sports events,” he continues. “Part of my job is providing an environment where they can do that, one that accommodates spending that time with family. People still have to do their jobs, but as managers in higher education, we have to recognize that one size doesn’t fit all anymore.”

In addition to being a proponent of a flexible work environment, Madden believes it’s his responsibility to develop people for the profession. “I take pride in people who have worked here and moved on to other roles at other institutions. I don’t discourage people from evaluating opportunities at other institutions,” he says. “I hope that’s a chance for them to grow and advance either at Iowa State or another institution. Staff members have gone on to be CBOs at other institutions.”

In summing up his career, Madden says, “For me, this has been a great experience. I don’t look back and regret staying here so long.” He and his wife, who is a former food science and human nutrition professor and career services director, plan to remain in Ames and continue volunteering at the university and in the community.

Of his future career path, Duryea says, “I don’t have a Ph.D., so I won’t ever be a provost or dean. I haven’t ruled the potential for a presidency in or out. Currently, I am learning as much about my current position and higher education in general as possible, but for the long term, who knows?”

While Duryea and Mazur are both new to their positions and were external hires, they see value in building talent internally and have started planning for the future of their respective business offices. “Succession planning is discussed at the college in general terms,” Mazur says. “I would say that my management team and I are self-directing this process in our area.”

Mazur has already had five staff retire during this tenure and expects more to come in the near future. “Several people on my team are in the advanced stages of their careers,” he says. “Fortunately, they are proactive and thinking about their departments beyond themselves.” Of those positions left vacant by retirements, one was filled internally while the rest were replaced through external hires.

In terms of his own role, Mazur and the president have not specifically talked about succession planning as they “both plan to be there for a while.” Still, thoughts about who might replace him will likely influence Mazur’s future hiring decisions: “When hiring an assistant vice president for financial operations, for example, I am looking for someone who has advanced credentials and progressively responsible management experience.”

Duryea’s approach is similar. “When hiring, I look for people who are not only going to work hard, but have initiative and are willing to tackle problems,” he says. “Also, I have an obligation as a supervisor to provide the training so that anyone who works for me can compete for the next position they desire. I don’t pick my successor, but I can provide staff with the opportunity to gain the skills, expertise, and education to go on to the next position if they so choose. From what I’ve seen, the university is good about providing opportunities for people who want them.”

Succession Startup

Even though CBOs can’t handpick their successors, opportunities for professional development and advancement are key to the future of the profession, asserts Mary Lou Merkt, vice president of finance and administration at Furman University, Greenville, S.C. “Succession planning is all about leadership training. We need a detailed plan to get everyone at Furman with potential up the ladder if they choose to go that route,” says Merkt, who has held her position for 13 years and is also the past president of the Southern Association of College and University Business Officers and the chair-elect for 2017–18 of the NACUBO board of directors.

Merkt, who serves on NACUBO’s succession planning committee, also notes, “The CBO profile survey has sparked an interest in succession planning throughout our profession for not only the CBO, but for other positions as well.” She acknowledges that it’s been difficult for a lot of CBOs, herself included, to “get their arms around putting a succession plan together.” Thus, it didn’t surprise her that so few institutions have formal plans in place. “It’s driven by our own perceptions and definitions of what succession planning is,” Merkt explains. “We have to get CBOs past the idea that they have to have an organizational chart that’s completely filled out.”

Instead, Merkt believes the emphasis should be on helping staff develop professionally. “At Furman, with each performance review cycle, we discuss leadership opportunities for each of my direct reports,” she says. “These might be opportunities for teaching, attending training, or broadening their job responsibilities. It’s important for me to ask them, ‘What is it that you can do to help yourself get to the next level?’”

Learn More about the NACUBO 2016 CBO National Profile

The 2016 National Profile of Higher Education Chief Business Officers is based on survey responses received from 713 chief business and financial officers at U.S. higher education institutions. The survey examines the CBOs’ personal characteristics and educational attainment levels; career paths they took to get to their current positions; areas of responsibility and skill sets needed to perform their jobs; levels of job satisfaction and areas of job frustration; and future career goals. This year’s study also includes new information on CBOs’ salary levels and succession planning activities. The 2016 CBO National Profile project is generously supported by TIAA.

The final report (NC9001) is freely available on NACUBO’s website in the Research section. To learn more about the findings of the report, listen to the NACUBO In Brief podcast episode, which can be found on the NACUBO website on the “NACUBO Podcasts” page.

As a manager, Merkt also sees value in getting another colleague’s perspective on potential leadership opportunities for her staff as well as potential skills gaps that may exist in finance and administration. This summer, she and the vice president for student life will sit down together and give each other feedback about their respective departments. “Select one colleague with whom you intersect a lot and whose judgment you trust,” Merkt suggests. “Then document those meetings with notes about where there may be opportunities for developing staff as well as challenges in terms of gaps in training or skills.”

Merkt’s best advice for CBOs to get started with succession planning is for them to take advantage of annual performance reviews. “It’s evaluation season at most institutions,” she points out. “If your evaluation tool doesn’t already have a section about leadership development, add it, have the conversation, and identify two to three leadership opportunities for each person.” Everyone on her staff has been given opportunities to make presentations at professional conferences. One of her direct reports chaired a staff advisory committee, while another started as assistant director of facilities and advanced to director, eventually taking on even more responsibility across campus. Adds Merkt: “I can’t think of a better retention tool than people knowing that you’re interested in them and their growth.”

Focusing on the Future

Knowing that she has opportunities for growth has influenced Kim Salisbury’s decision to remain at the University of Idaho (UI), Moscow, for almost five years. “There are lots of benefits to being here,” she says. “One of them is that they encourage us to be involved in professional development.” Salisbury joined the university’s business office as an accountant and was promoted to academic budget officer earlier this year.

During her tenure at the university, she obtained her certified management accountant designation and also attended NACUBO’s Future Business Officer Program in 2014. “I look for professional development programs that will benefit me in the future,” Salisbury says. “For instance, I will be attending a conference on academic program costing that will be helpful in my current role.

“In the FBO program, we talked a lot about mentoring,” she continues. “I keep in contact with one of the presenters I met there. One of my goals for attending conferences is to create a network that I can rely on now and in the future.” Salisbury acknowledges that she’s really in the beginning stages of preparing for the CBO role, but she plans to keep in contact with others on the same career path, while continuing to show her current institution that she’s willing to take steps toward that career goal.

How did Salisbury become interested in the CBO role? A graduate of UI, she initially came back to the university as an accounting instructor and then returned to work in the business office five years later, after having her son. By working in the general accounting office, Salisbury had lots of interaction with the CBO. “I knew the CBO and liked working with him,” she says. “I also liked the content of his job, which involves strategic planning and decision making. Just working in accounting wouldn’t give me that experience. The business office is a good anchor point within the institution.”

While Salisbury wasn’t aware of a formal succession planning process at UI overall, or specifically for the business office, she believes there are definitely opportunities for her there. “If I had my sights set on one particular position, that might be difficult,” she admits. “There’s a lot of movement in higher ed. If you’re really interested in the CBO role, you have to be prepared to move around.”

Hiring for Resources

Staci Sleigh-Layman, executive director of human resources at Central Washington University, Ellensburg, Wash., knows all too well that staff sometimes leave to pursue opportunities at other institutions. CWU’s chief business officer left earlier this year, and the university appointed an interim chief financial officer and vice president for business and financial affairs. From Sleigh-Layman’s perspective, filling these positions presents an opportunity to think about succession planning.

“Part of HR’s role in hiring new staff isn’t just filling current gaps,” she says, “but identifying people who will qualify for the next position after the one for which they are being hired.” She encourages hiring managers to evaluate job candidates’ overall skills and aptitudes rather than only their ability to perform specific tasks. Sleigh-Layman concedes that CWU doesn’t “have an institutional culture that has always thought about succession planning, but we’re working on it.”

“You can invest proactively or spend even more when you have to fill a position.”

—Staci Sleigh-Layman, Central Washington University

At CWU since 1984, and in HR since 2009, Sleigh-Layman doesn’t recall ever getting a promotion without going through a national search. “I’ve been promoted at CWU via two national searches. I take great pride in that. There’s credibility that comes from competing for positions,” she says. “CWU’s job is to prepare internal candidates to compete nationally for positions.” She believes that the preparation is a shared responsibility. “It’s important for the university, over an employee’s tenure, to provide opportunities for growth and development. But it’s also up to the individual to do career planning, ferret out experiences that can be useful, and take advantage of available opportunities.

“You don’t get extra points for just being at CWU,” she continues. “You get points for having the experience and having done the work.” To that end, Sleigh-Layman believes higher education institutions have the responsibility to invest in the profession by making professional development readily available to staff. “It’s up to the organization to ensure that opportunities are made available to those individuals who want to do more and work toward professional goals,” she says. “We have to invest in people, knowing that at any given time they might leave.

“We owe something to the profession,” she emphasizes. “We’re not just planning for our own succession; we’re planning for someone else’s as well. If we can’t provide that growth opportunity, another institution might be able to.” Given CWU’s location just two hours east of Seattle in a city with a population of about 19,000 (9,000 of whom are students), Sleigh-Layman recognizes that the institution, which has 1,500 permanent full-time employees, doesn’t have the same flexibility in filling positions that an urban center might have.

She also knows that the idea of spending time and money to develop staff is a “tough sell” to some supervisors, who view this as a drain on resources. “It’s going to cost you one way or another,” Sleigh-Layman stresses. “You can invest proactively or spend even more when you have to fill a position.” To encourage broader thinking about professional development, CWU’s human resources division launched an online succession planning guide (www.cwu.edu/hr/succession-planning) six months ago with the theme, “Prepare the right people for the right jobs at the right time.” So far, HR has used the guide to consult with two high-level supervisors—impacting approximately 50 employees. According to Sleigh-Layman, “those two report back that, while there isn’t always buy-in from everyone, people are starting to think about their work lives differently.”

Admittedly, this is a small step, but it’s a start. “Our goal is to plant the seeds that get people excited about their prospects and looking for professional development opportunities,” Sleigh-Layman says. “We have to educate employees and their supervisors so that they can make their relationships fruitful for the institution.” If those relationships blossom, hopefully institutions will have a clearer idea of who’s next in line for leadership roles in the business office.

APRYL MOTLEY, Columbia, Md., covers higher education business issues for Business Officer.