Isaac Newton coined the phrase “What goes up must come down.” But, in the tuition-discounting world, when tuition goes up, the related discount rate tracks right along with it. The hope is that the combination, designed to show the institution’s quality while making it more affordable, won’t send net tuition revenue plummeting.

Isaac Newton coined the phrase “What goes up must come down.” But, in the tuition-discounting world, when tuition goes up, the related discount rate tracks right along with it. The hope is that the combination, designed to show the institution’s quality while making it more affordable, won’t send net tuition revenue plummeting.

For the past couple of decades, private, independent institutions have explored differing combinations of the factors intended to attract additional students while increasing net tuition revenue, or at least keeping it stable.

NACUBO’s 2013 Tuition Discounting Study (TDS)—which reports discount data for the 2012–13 academic year as of fall 2013 and makes preliminary estimates for the 2013–14 academic year—indicates that the goal of finding the right pricing formula continues to elude many institution leaders.

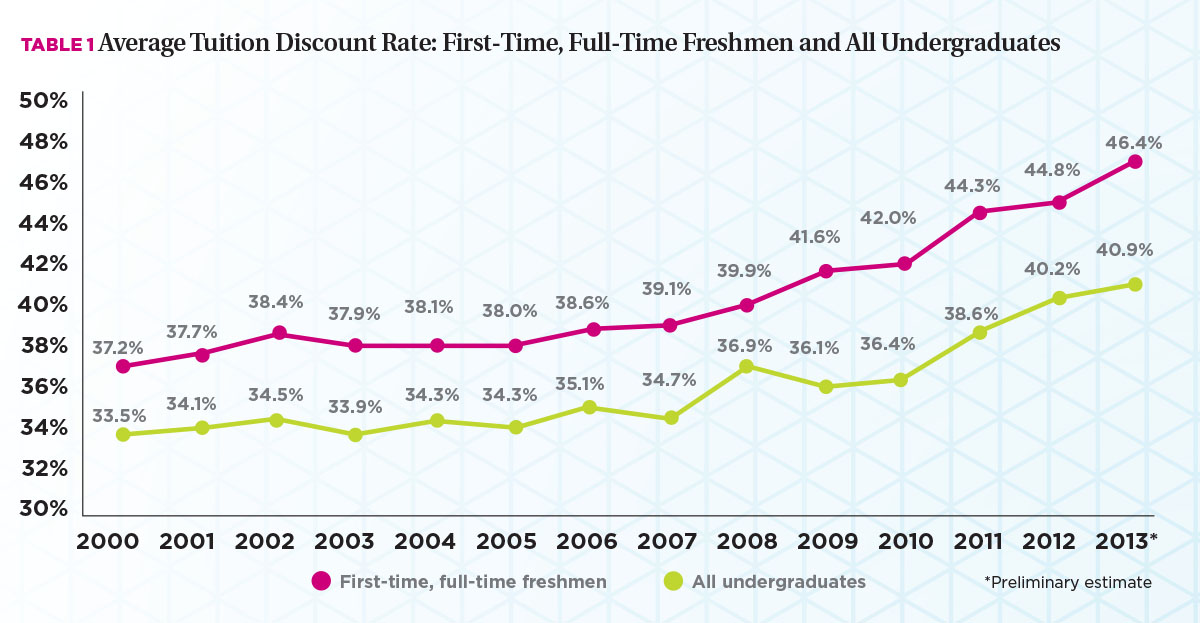

According to Natalie Pullaro Davis, NACUBO’s manager of research and policy analysis, “In academic year 2013–14, institutions gave back 46.4 percent [that year’s average tuition discount] of their freshmen revenue to students in the form of scholarships and grants, up from 44.8 percent the year before.” (For details, see Table 1.)

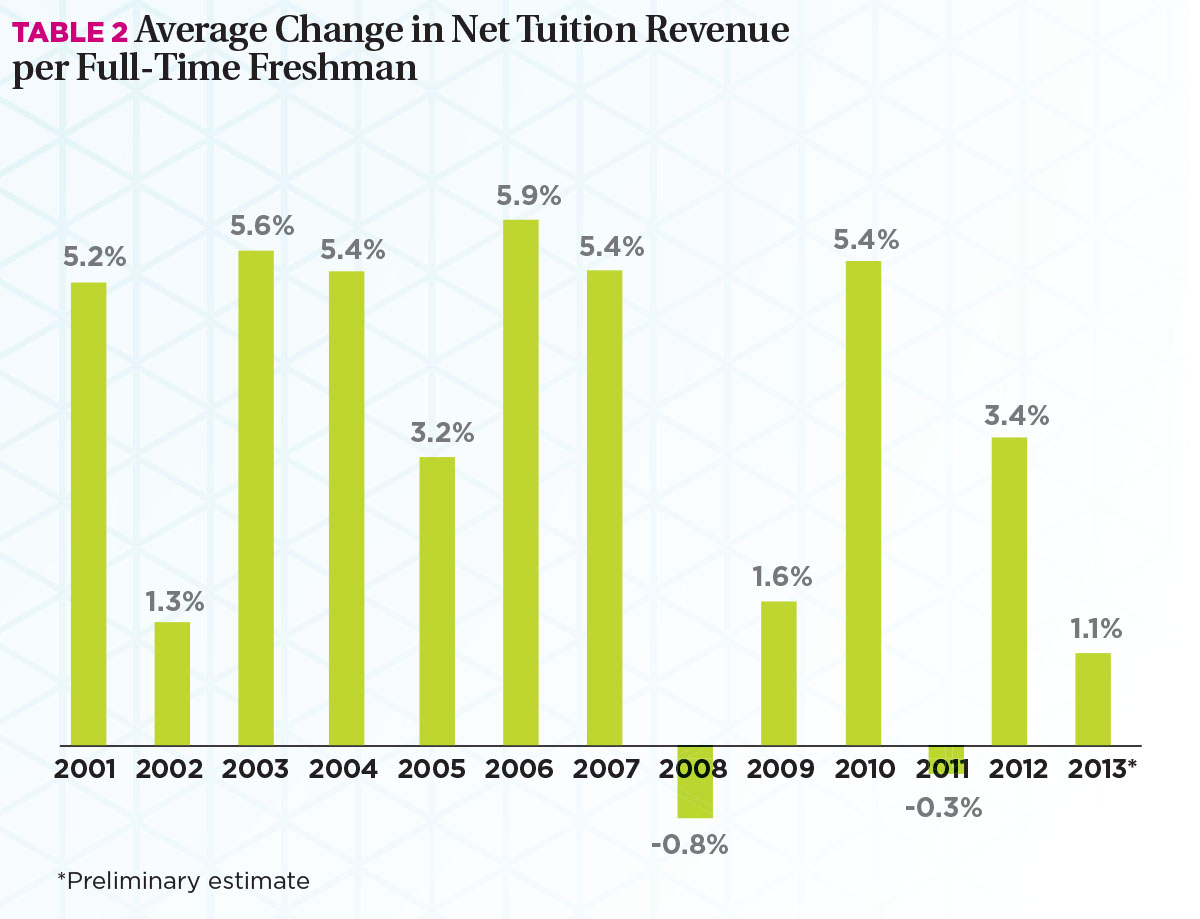

Further, says Davis, author of the 2013 Tuition Discount Study, “Private institutions continue to hit headwinds when trying to grow net tuition revenues. The average change in net tuition revenue per student for 2013–14 is projected to be only 1.1 percent.” This compares to an average percentage change of 3.4 percent in 2012–13 (see Table 2). “Institutions are being very cautious about raising tuition and fee prices any further than necessary,” she says. “Generally speaking, students’ ability to pay is an increasingly important factor.

“For some institutions,” says Davis, “softening demand has motivated decision makers to explore a new approach to pricing—to try something new and drop out of the so-called ‘arms race.’ This year’s study identified several institutions that actually decided to lower tuition. Although the idea of a price cut isn’t novel, if it achieves an institution’s goals, it could be a worthwhile move.”

Pricing Resets

Take, for example, Concordia University in St. Paul, Minnesota, which last fall dropped its tuition by $10,000—from $29,700 to $19,700—and its corresponding discount percentage from the mid-40s to the low 20s. The result: The number of incoming freshmen jumped from the 180s to the 250s, and next year’s class is keeping up that pace and a similar discount rate, says Eric LaMott, senior vice president and chief operating officer.

“Students have been coming from all over the place,” he says. “We had students transfer from other private schools to our institution, saying they always wanted to go to our style of institution but felt it was cost-prohibitive based on the tuition amount. The tuition-reset model for us has worked out very effectively.”

LaMott believes the days of superinflated tuition levels, with artificial discounts ranging from 40 to 60 percent, may be coming to an end, because families no longer define the quality of the university experience by the annual sticker price. “Many consumers have moved away from that perspective toward a more transparent tuition expectation,” he declares. “They are looking for a quality academic program that will get their son or daughter what he or she wants to achieve.”

Another institution, Ashland University, Ashland, Ohio, recently announced a tuition price reduction of more than $11,000. Next year’s undergraduates will pay just over $18,000, down from $29,000-plus. Scott Van Loo, vice president for enrollment management and marketing, projects that next year’s freshman discount rate will average 35 to 36 percent, down from around 58 percent this past year.

“We pulled together a price-point committee to look at the future of the institution and started to forecast models seven to eight years ahead. When we looked at the trajectory, we ran into some alarming scenarios,” Van Loo recalls. “We saw that in seven years the total cost to attend this institution would be well over $50,000; and our discount rate would mostly likely be up around 70 percent, if we continued on the same trend line. When you reach that point, you have a real financial challenge as far as your model and sustainability in moving forward.”

In the region where Ashland is recruiting, “It’s apparent a price war is taking place,” Van Loo insists. “We have so many institutions and a declining availability of high school students to recruit. When all other variables are considered, such as the distinguishable qualities of each institution, once students decide on their final two or three institutions, they are heavily weighing price.”

Van Loo readily admits that Ashland’s new lower-priced tuition model isn’t a one-size-fits-all strategy. “As an institution that implemented a price reset, we’ve been asked about it throughout the course of the year,” he says. “I don’t necessarily believe that our decision is the decision that every institution should reach. It’s important to understand who you are serving, what you are trying to accomplish, and who you are trying to attract as students—and then find the best model in terms of pricing for them.”

What Gives?

These two institutions—and others—are responding to changing demographics, intense competition from both private and public institutions in their regions, and laser-like scrutiny by students and families on out-of-pocket costs, notes Davis.

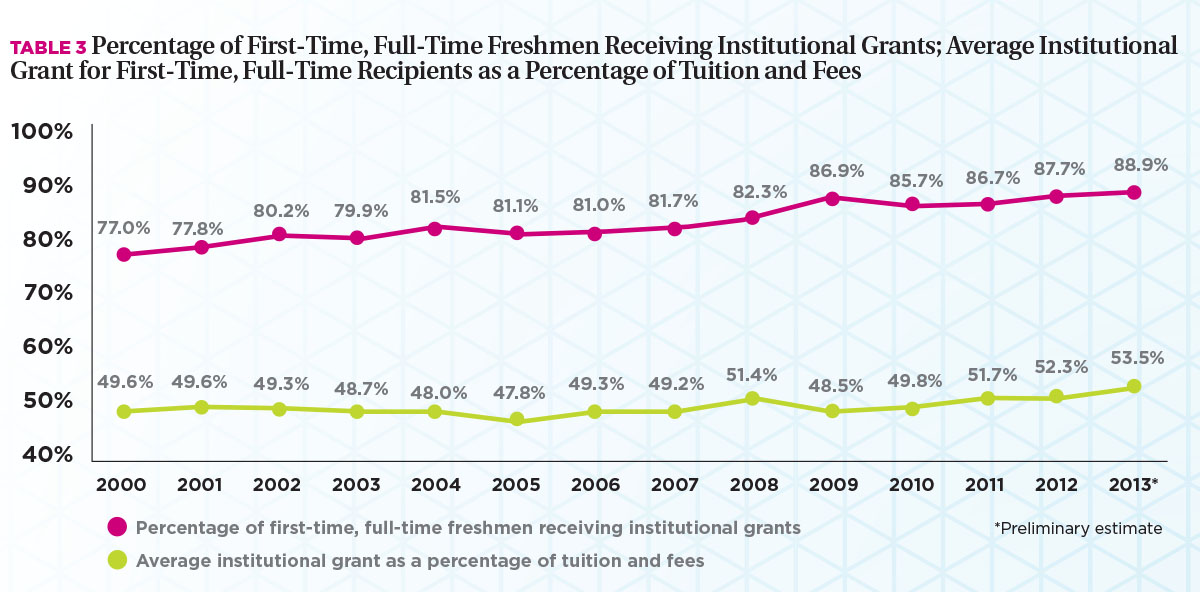

The fact that ever more numbers of students are receiving institutional aid is also telling (see Table 3). “This year’s study shows that the share of freshman students receiving an institutional grant continues to grow,” says Davis. “The percentage of freshman grant recipients is nearly 89 percent, up from 80 percent a decade earlier. The average freshman grant now covers 53.5 percent of the price of tuition and fees.”

Kathy Kurz, vice president, Scannell & Kurz, a RuffaloCODY com-pany in Pittsford, New York, agrees that families are looking for value as they comparison shop among private and public institutions in their quest for a college education.

“We’ve already seen, as early as 2010, trends showing that more and more families are interested in sending their children to community colleges for the first couple of years, even if the intention is to go on to complete a four-year degree,” Kurz says. “There’s concern about borrowing and return on the investment.”

The TDS analysis further supports this trend. For the second year, the study asked CBOs at institutions that have been gaining and losing freshmen enrollment over the past three years what they thought were reasons attributing to the loss or gain. Of CBOs at institutions that lost freshmen enrollment, 57.4 percent thought that price sensitivity of students and families was to blame. Half also thought increased competition from both public and other private institutions played a role. Conversely, 36.7 percent of CBOs at institutions with growing enrollment attribute this growth to increased financial aid.

To Each His Own

Obviously, every institution has its unique characteristics with regard to competitive advantage, location, reputation, and the like. “When we consider strategy, we cannot take a cookie-cutter approach,” says Kurz. “It’s so critical for institutions to understand the price sensitivity of their markets and respond to that information. Unless you base your policy on data, it’s easy to slip into a situation where you’re trying to outbid the institution next door. Pay attention to your real competitors, so you understand how your institution stacks up in terms of sticker price, tuition discount, and prestige.”

Suppose, she says, one of your institution’s goals is to increase its quality profile or its geographic diversity; you may find that certain subpopulations are more expen-sive from a financial aid standpoint than others. “The goals of the schools themselves can influence how much a class costs in terms of financial aid and discount rates.”

Unless you have the resources on your campus to conduct sophisticated analyses, both Kurz and LaMott recommend looking for an experienced external partner. LaMott points out that when Concordia reset its tuition, “We spent almost six years analyzing options and discussions before settling on this execution and strategy. We worked with competent partners to help evaluate this so we would have third-party validation to our structuring and modeling. That’s really important. All schools can benefit from an external set of eyes.”

When determining its discount rate, Bellarmine University, Louisville, Kentucky, a private Catholic university with more than 2,500 undergraduates students, uses a mathematical model, created by Maguire Associates, to consider its options. The model, a technique Bellarmine has employed for the past 12 years, considers 10 to 15 variables relating to each student, such as geographic area and ZIP code, SAT or ACT score, high school grade point average, gender, the location where the student lists Bellarmine on the FASFA form—and other schools to which he or she has applied.

“The Maguire model spits out an award based on the past history of the students who have accepted and come to Bellarmine,” says Robert Zimlich, vice president for administration and finance. “We have to compete with a very inexpensive public market here in Kentucky. Our largest cross-applications are with the University of Louisville and the University of Kentucky, which have tuition rates of less than $10,000 a year.” (For details on Bellarmine’s pricing strategy, see sidebar, “New Strategies Reap Rewards.”)

Decisions and Trade-offs

When working with higher education clients to determine a tuition strategy, Kurz finds herself repeating a single mantra: “Study the data.” That’s because what produces splendid results at one institution may cause chaos and calamity at another. For example, she says, it’s important to know some very basic data points, such as the yield rates for specific subpopulations, how much tuition is currently being discounted for those populations, and how much yield can be affected by changes in discount.

“We would encourage all institutions to study their own data,” says Kurz. For example, look at how the students you have offered admission and aid to in the past responded to those offers, so you understand better how they might respond to a somewhat different discount rate.”

After coming to terms with the analytics, Kurz recommends that at least three key people—the chief financial officer, chief enrollment officer, and chief academic officer—each have a say in the institution’s discount rate, so each understands the trade-offs involved in raising or lowering the rate by a notch or two.

“You might be able to bring down the discount rate, but it could mean a class or cohort that is not as strong academically, or it might mean a class that is geographically or ethnically less diverse,” she says. “It might mean a smaller class. In some cases, lowering the discount rate can increase net revenue, which is often the assumption the chief financial officer makes. But, this is where data become important; in some cases, if the market is very price elastic, lowering the discount rate could lower net revenue, because you lose so many students.

“Understanding that dynamic and those trade-offs involves lots of different people on the campus,” she continues. “It can’t be one person’s or one unit’s decision.”

Van Loo suggests that institutions with formidable discounts might want to forecast tuition levels for the next 10 or 15 years to determine what looms ahead. “At some point, you run into the price elasticity challenge where the cost will exceed the perceived value,” he says. “We in higher education can’t become so expensive and our discounting model so hard for families to understand that we become less and less attractive to the general society.”

MARGO VANOVER PORTER, Locust Grove, Virginia, covers higher education business issues for Business Officer.