FIRST IN A SERIES Rising college prices and student debt loads, coupled with the challenges of finding meaningful employment when students graduate into weak economies, have helped reignite a long-simmering debate about the role of higher education in our communities, our society, and our economy. Further complicating public discussion and understanding of the issues at the heart of this debate are the changing demands on the nation’s workforce, rising global competition, calls to increase the share of Americans who have a college degree, and uncertain funding for colleges and universities. Put most simply, questions are increasingly being raised as to whether the higher education system in the United States provides good value.

Recognizing these challenges to the sector, the NACUBO Board of Directors included in the association’s current strategic plan an initiative to develop and disseminate key messages on the value of higher education. Two board committees then guided the development of NACUBO’s communications messages and strategies for describing the value of a higher education. After identifying those values to individuals and society—as well as the benefits that colleges and universities bring to their communities—the board adopted several recommendations for association action.

This series, on the value of higher education, launches NACUBO’s efforts to offer perspective, messages, and data to our members. In this issue, noted researcher and author Sandy Baum offers a detailed, thoughtful, and nuanced analysis focusing on the value to students of attending college. Her frank assessment of the widespread benefits of a college education, as well as areas where the value is less clear, concisely describes the fuel that drives today’s public debate.

Forensic Scientist

College degrees significantly improve earnings and career prospects for the vast majority of students.

Next month, Business Officer will feature another article in this series, highlighting individual students whose personal stories illustrate a critical and overarching message; namely, that a college education provides a lifetime of value. In the fall, another article will explore the value that colleges and universities provide to their respective communities and economies, illustrating that our campuses serve their surrounding areas in countless ways while helping them thrive.

Beyond the articles that will comprise this series, NACUBO will distribute additional materials for your use, as you engage with colleagues across campus to remind our numerous stakeholders of the value of higher education to our students, our communities, and our society.

For people deeply engaged in the higher education enterprise, many of whom have dedicated their lives to increasing the educational opportunities available to a broad range of students, it may be difficult to accept the current level of doubt about the value of college that permeates many discussions across the country. After all, as college and university educators and administrators, we are aware of several significant facts:

- College graduates earn significantly more than high school graduates.

- Many rewarding occupations require a two-year or a four-year degree.

- A variety of factors—including health, longevity, satisfaction with work, and civic engagement—are correlated with levels of educational attainment.

So, do we really need to defend the value of a college education? Yes, in fact, we do. The reality is that as tuition prices have risen in an economy where few people see their earnings rising faster than the prices of goods and services, and as student debt has captured the imagination of the press and the public, many people are questioning whether going to college is “worth it.” It’s a fair question.

The simple truth is that the vast majority of people will be better off if they go to college than if they don’t; but that answer is no longer sufficient. Being able to provide the evidence about the average payoff of a college education remains central. It’s also important to understand the variation in the postsecondary paths available to students in this country and the range of outcomes that students experience. The students who make headlines for working in Starbucks after they graduate from college or for accumulating $70,000 or more in debt to pay for their undergraduate education are quite rare. But, they are real, and evidence about the high return on a college degree is more credible if it accounts for these outliers.

Most people who work on college campuses see up close the opportunities available to students, the ways students grow and learn while they are in school, and the life-changing nature of many college experiences. The public focus on earnings in the first few years after college misses much of the value of higher education for students over a lifetime. Continuing to emphasize the other benefits to the public and policymakers is critical, but that doesn’t make the financial returns unimportant. And, because the latter are easiest to measure (although not so easy as some ratings systems would suggest), it is useful to have the information at hand.

Some advocates for increased public support for higher education object to focusing on earnings, not so much out of concern for downplaying the other benefits students get from education but because they prefer to focus on the benefits to society of a more educated population, rather than on the benefits to individuals. It is true that we are all better off when more people have quality higher education experiences. Collectively, we have a more productive labor force producing more wealth, we spend less on income support programs designed to fight poverty, and we have a more engaged and informed citizenry. But, the reality is that these public benefits do not diminish the considerable advantages accruing to the individuals who participate and succeed in higher education. It is precisely because there are such large personal benefits that it is so important for people from all backgrounds to have access to college, regardless of their ability to pay.

Journalist

Many rewarding occupations require a two-year or a four-year degree.

The Earnings Payoff

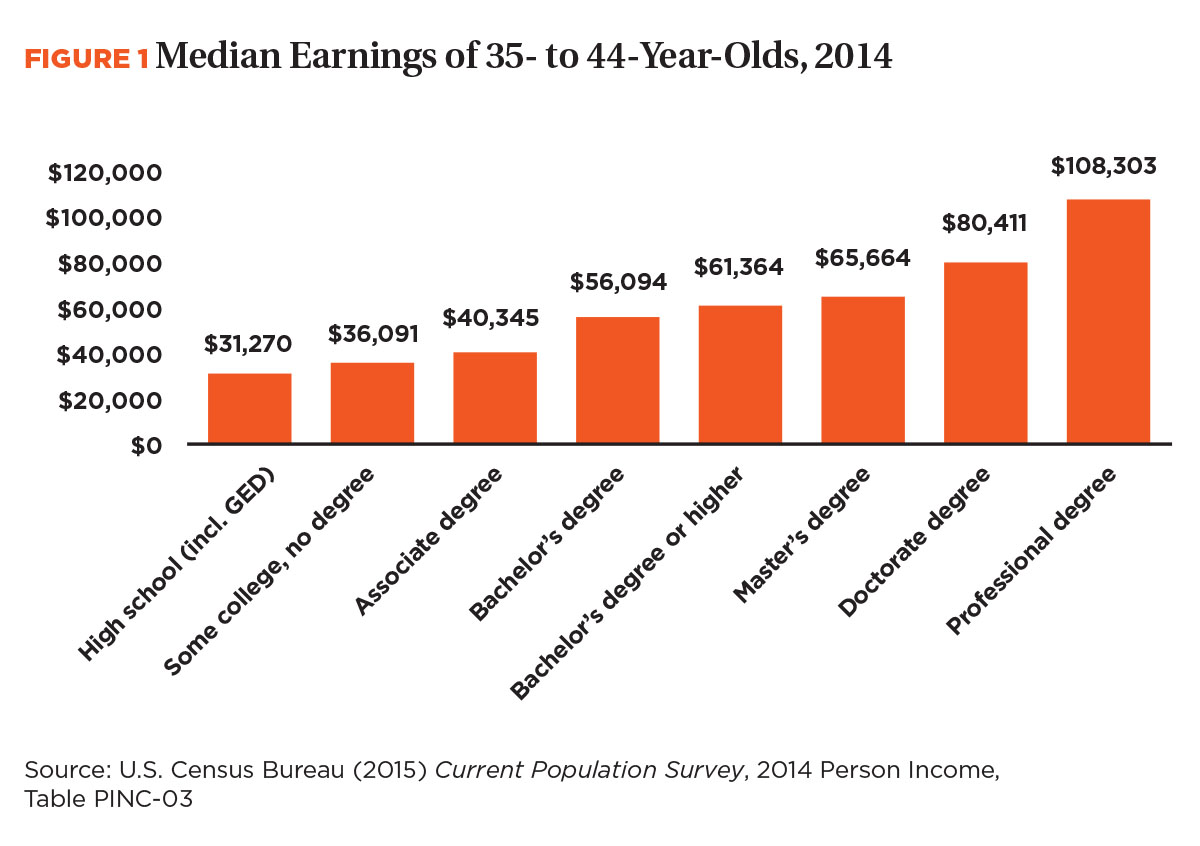

The typical financial gains from earning a college degree are quite large. According to data from the U.S. Census Bureau (see Figure 1), in 2014, when median earnings for high school graduates ages 35 to 44 were $31,270, associate degree holders earned 29 percent more, and the median for individuals whose highest degree was a bachelor’s degree was $56,094—an increment of 79 percent. If you include those who went on to earn advanced degrees—including the 13 percent of that group who have professional degrees and median earnings of $108,303—that raises the median for four-year college graduates to $61,364.

Earnings data can be sliced in many ways. For instance, focusing only on full-time, full-year workers raises the earnings level for each group and narrows the gap between high school and college graduates a bit. It excludes more people without college degrees because those with more education are more likely to work, and when they work, to work full time. Choosing a younger age group narrows the gap because the earnings of more educated workers rise more rapidly as they progress in their careers. But, the basic story remains the same. The earnings differentials by education level are very large for all age groups, for both genders, and for all racial and ethnic groups.

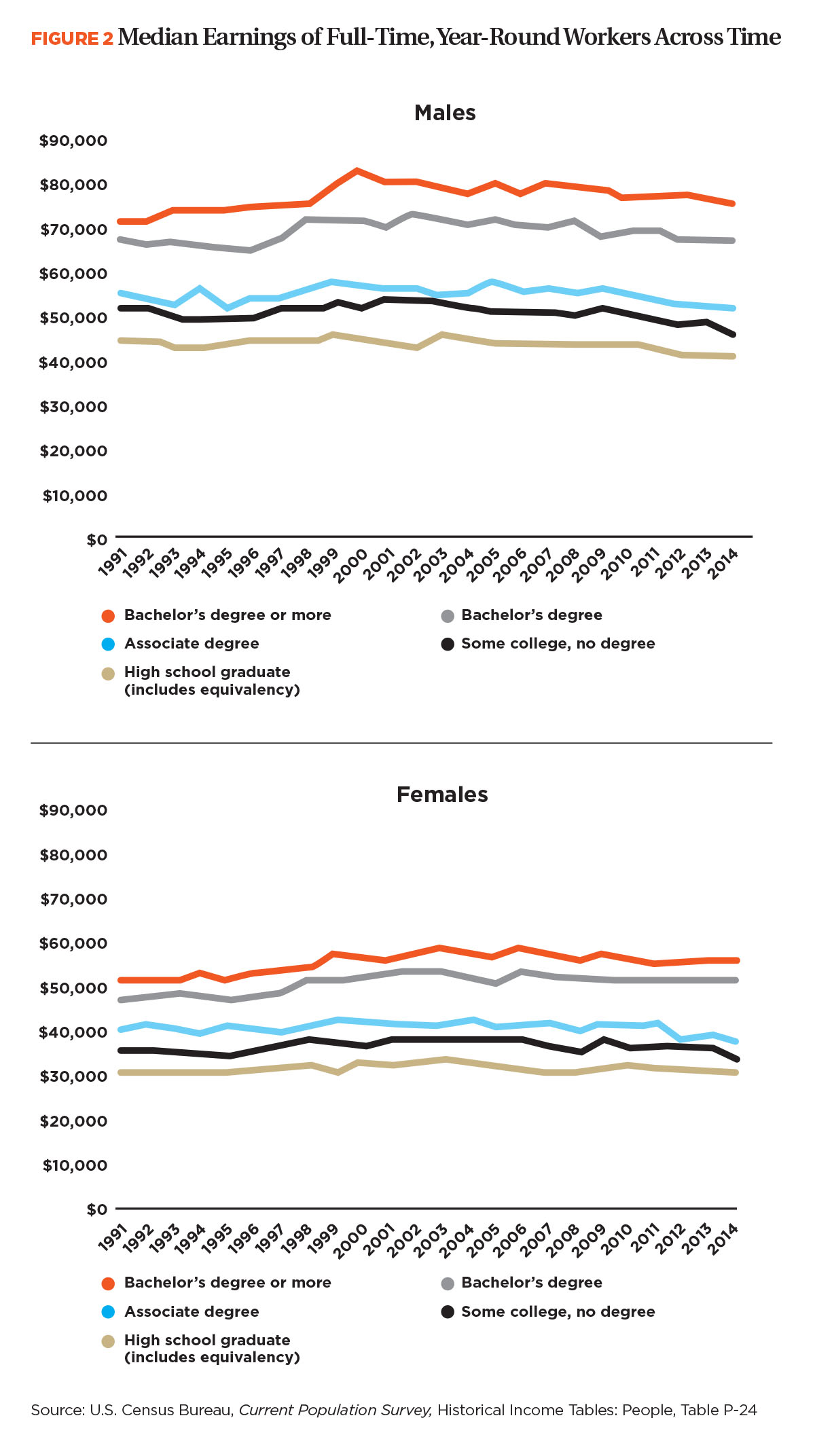

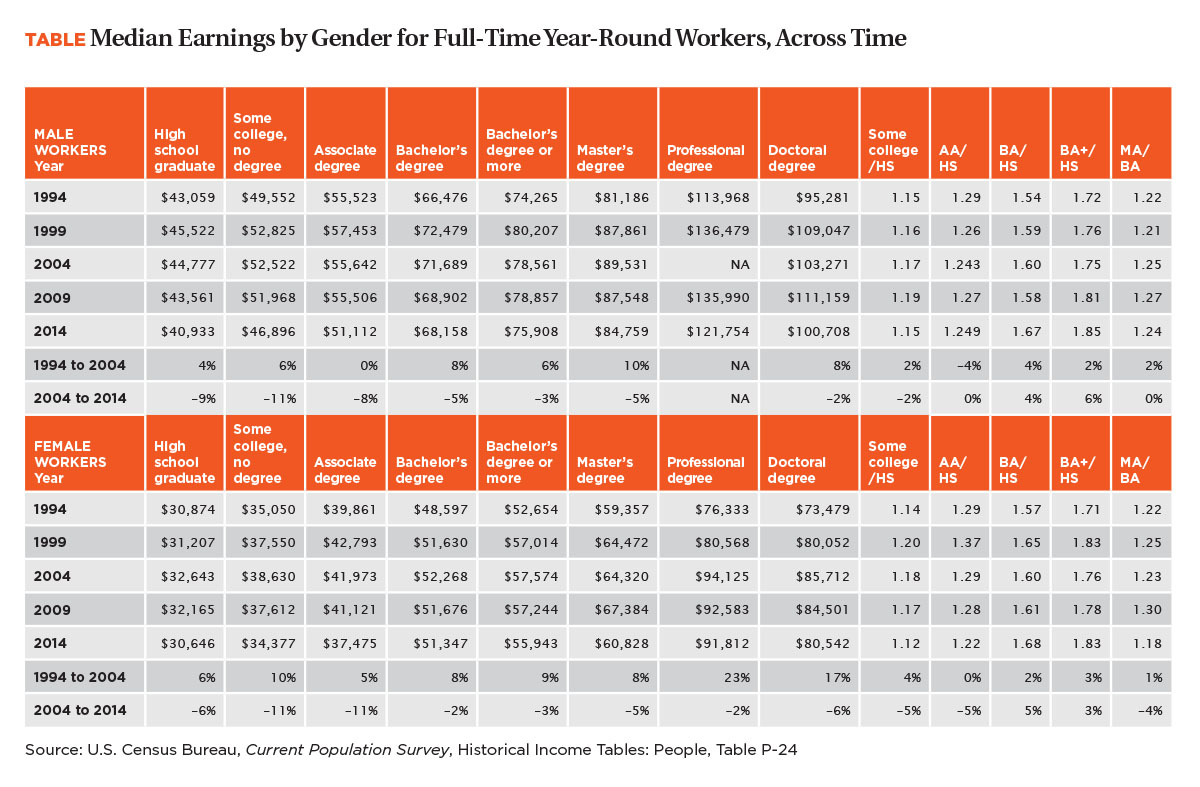

What about the argument that the earnings of college graduates have been stagnant or even declining? Median earnings of full-time workers, adjusted for inflation, fell for both men and women at all levels of education between 2004 and 2014, including a 5 percent decline for men and a 2 percent decline for women whose highest degree was a bachelor’s degree (see Figure 2). With rising college prices over this decade, it is certainly true that it became more difficult to pay for college out of future earnings.

Yet, this is not the same thing as a decline in the payoff from a college education. The earnings gap between high school graduates and those with bachelor’s degrees rose from 60 percent for both genders in 2004 to 67 percent for men and 68 percent for women in 2014. This occurred because the earnings of high school graduates declined much more over the decade than the earnings of four-year college graduates.

The story is not the same for all groups of college graduates. On average, men ages 25 and older with associate degrees earn 25 percent more than high school graduates, and the earnings premium for women is 22 percent. But the premium for men was the same in 2014 as in 2004, and the premium for women declined.

Earnings in Context

The fact that the median earnings of individuals with bachelor’s degrees are almost 70 percent higher than the median earnings of high school graduates does not mean that every person who goes to college will see this earnings bump. For one thing, these figures do not prove that college is the cause for the entire earnings differential. Those who go to college and earn four-year degrees are not randomly selected. They may well have some characteristics that would cause them to earn more than the average high school graduate, even if they did not continue their education after high school.

Musician

Maximizing future earnings is not the central goal of higher education.

Cause and effect. While it is difficult to sort this out precisely, careful statistical studies suggest that, in fact, college does cause most of the difference in earnings. (Two such studies include “The Causal Effect of Education on Earnings” in the Handbook of Labor Economics (North Holland, 2010); and “Consequences for the Labor Market,” in The Price We Pay: The Economic and Social Consequences of Inadequate Education (Brookings Institution Press, 2007). How much of this effect is the result of real improvements in knowledge and skills and how much is attributable to the signal provided by the credential is unclear. However, from the perspective of an individual deciding whether to pursue a degree, that distinction is not so critical.

Variation in incomes. Another issue is the considerable variation in the earnings of people with similar levels of education. Where one goes to college and the quality of one’s degree do seem to matter. Moreover, different occupations are rewarded differently in the labor market. Among full-time, year-round workers with a bachelor’s degree or higher, median earnings for those in legal professions are 55 percent higher than the average, and earnings for engineers are 39 percent higher than the average. In contrast, those in education earn 22 percent less and those in arts and entertainment have median earnings 14 percent below the average (U.S. Census Bureau, American Community Survey 2012). The variation in earnings means that it is not difficult to find a four-year college graduate who earns less than a high school graduate.

Again, according to U.S. Census Bureau statistics (Current Population Survey 2014), among full-time, full-year workers ages 35 to 44 who have a bachelor’s degree or higher, about 18 percent earn less than the median for high school graduates in that age range. Among associate degree holders, 36 percent earn less than the high school median. About 17 percent of high school graduates and 28 percent of adults between the ages of 35 and 44 whose highest degree is an associate degree earn more than the median for individuals whose highest degree is a bachelor’s degree. The key point is that while the distributions of earnings overlap quite a bit, overall, average earnings increase with level of educational attainment, and most four-year college graduates earn more than most associate degree holders, who earn more than most high school graduates.

Fine Artist

Even if there were no uncertainty about the future [and earnings], the role of education in developing personal, intellectual, and social skills is vital.

Debt debates. While reporters find stories about high school graduates who do unusually well—and about college graduates who struggle mightily— much more interesting than the reverse scenario, the overall differences are quite clear. Similarly, stories about students who borrow typical amounts for their undergraduate education, go to a four-year college, and graduate with a bachelor’s degree after four or five years rarely make headlines. According to the National Center for Education Statistics (2011–12 National Postsecondary Student Aid Study 2012), only 9 percent of 2011–12 bachelor’s degree recipients borrowed more than $100,000, and 9 percent graduated with more than $50,000 in debt. Only16 percent of associate degree recipients borrowed more than $20,000. These high levels of debt are far from typical.

The students who borrow more than the average for their degree attainment tend to be older students, those who attend for-profit institutions, and those who take a long time to earn their degrees (Trends in Student Aid 2014, The College Board). A disproportionate number of the borrowers struggling with student debt borrowed small amounts but left school without any sort of credential. In other words, the popular image of the underemployed bachelor’s degree recipient burdened down by debt is not representative, though some individuals do end up in this situation. Rather than pretending that the outcomes of college are always positive for everyone, it makes much more sense to focus on the very high returns, but put the less favorable outcomes into context and work to make them even less common than they now are.

The Recession Road Bump

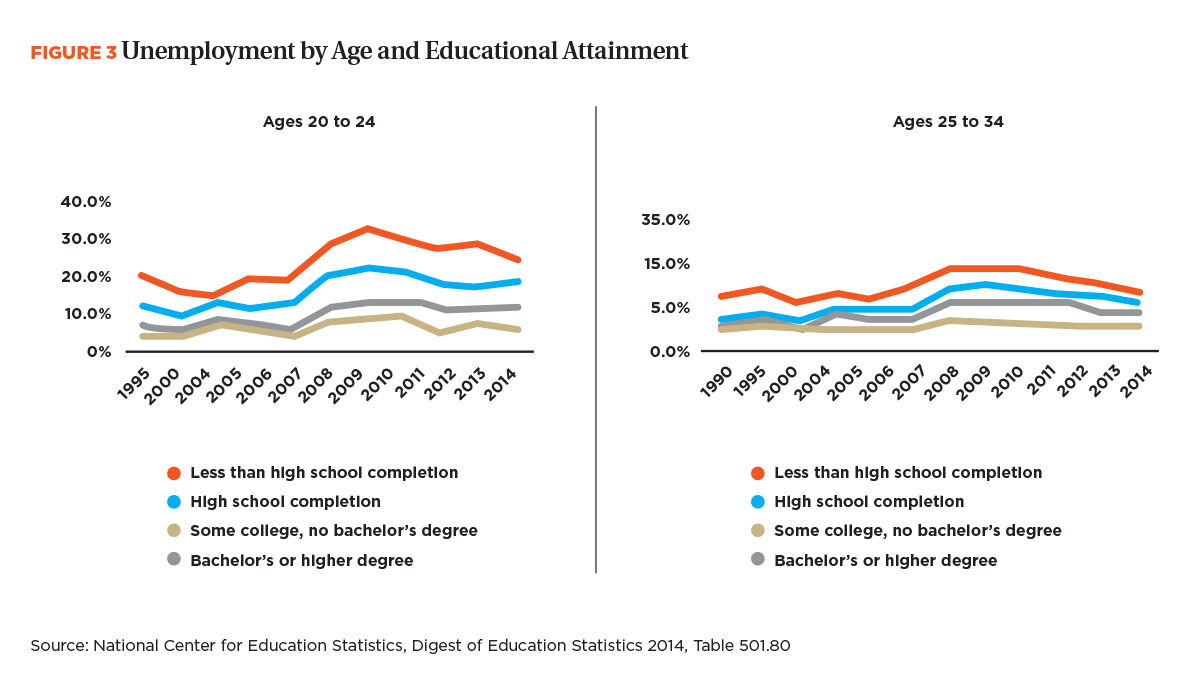

It is no accident that concerns about the value of a college education became more prevalent during the Great Recession and its aftermath. As noted above, earnings suffered across the board. The value of homes and stock portfolios plummeted. There were certainly more unemployed recent college graduates during these years. The unemployment rate for 20- to 24-year-olds with a bachelor’s degree or higher rose from 4.5 percent in 2008 to 8.7 percent in 2011 before falling back to 6.7 percent in 2014 (see Figure 3). The unemployment rate is always highest for younger people. The unemployment rate for 25- to 34-year-olds in this educational attainment group rose from 2.2 percent in 2008 to 4.3 percent in 2011, and dropped to 3.7 percent in 2014.

Judging the value of a college degree also requires comparing college graduates to others, not simply observing their plight in the depths of a recession in isolation. For instance, for high school graduates ages 20 to 24, the unemployment rate was alarmingly high during the recession, rising from 13 percent in 2008 to 21.6 percent in 2011 and dropping only slightly to 18.9 percent in 2014. And, for 25- to 34-year-olds with only a high school education, unemployment rose from 8.5 percent in 2008 to 14.3 percent in 2011 before settling at 10.5 percent in 2014.

What Students Need to Know

College degrees significantly improve earnings and career prospects for the vast majority of students. Yet, simply telling students to go to college because of the high payoff is not sufficient. Making prudent decisions depends on understanding the wide ranges of institutions and programs available and of the prospects for success associated with these different options. The Obama administration has put considerable effort into increasing the amount of information available to prospective students. After abandoning an effort to devise a ratings scheme for colleges and universities, the administration launched its College Scorecard site. Much of the information—which includes prices, financial aid, student debt, graduation rates, and other information about student body and programs offered—was already available on the Department of Education’s College Navigator site.

The new scorecard site adds data on the earnings of students 10 years after they first enrolled. Providing this information is controversial. Aside from questions about how potential earnings should play into students’ decisions about college, the data are far from perfect. A key issue is that information is only available for students who received federal financial aid. There are also questions about how useful averages are to individual students. For instance, if a student is planning to study engineering at a liberal arts college, should he or she worry that the average earnings are lower with a degree from there than from a college where engineering is the most popular major? Should the gender gap in earnings discourage a woman from her first choice of attending a single-sex institution?

Heart, Mind, and Wallet

A fundamental question is how to think about the role of future earnings in determining decisions about where and what to study. Maximizing future earnings is not the central goal of higher education. Even if there were no uncertainty about the future, the role of education in developing personal, intellectual, and social skills is vital and should be a motivating factor for students. As a society, it is clearly counterproductive to discourage talented students from entering education and other public service fields. Likewise, suggesting that everyone should study engineering because of the high wages in that area could lead to many failed college experiences among students with very different interests and strengths.

Veterinarian

Completing education and building on it in the labor market is a starting point for a secure and satisfying life.

On the other hand, ignoring the financial outcomes of postsecondary education is also irresponsible. Maximizing income may be an unfortunate goal, but finding a career that will be both satisfying and ensure financial security is vital for most people. The financial payoff to a college education matters a lot. Steering students away from institutions with very low graduation rates and with little employment success for graduates is an important component of increasing educational opportunities.

Unfortunately, how to steer students in positive directions is not as straightforward as creating a website full of data on institutional outcomes. First, the students most in need of guidance are probably those least likely to be surfing the Web in search of information. Many disadvantaged students whose parents have little or no college experience often lack access to adequate high school counselors. They typically go to under-resourced schools or have already been out of high school for a number of years. They may not even know what questions to ask. For most students, the college nearest to home with the lowest price tag—or the college with the most prominent ad in the subway—seems like the best option.

Clearly communicating the value of a college education to these students is critical, but they need to know more. They need personalized advice about the differences among community colleges, for-profit institutions, and four-year colleges and universities. They need to know what kinds of jobs are available to certificate holders, to those with associate degrees in general studies, and to those with more career-focused, two-year degrees. And, they need to know which paths are more likely to lead to bachelor’s degrees if that is their goal.

The Cost Conversation

Chief business officers and other campus administrators not directly involved in the admissions process may think more about motivating current students than guiding initial enrollment decisions. Getting through college is a challenge for many students. While we certainly hope they are motivated by their intellectual engagement and their desire for personal growth, we should not hesitate to clarify the financial implications of completing a degree—or of dropping out without one.

As detailed here, earnings are highly correlated with educational attainment. The gap between the earnings of individuals with some college but no degree and the earnings of high school graduates has not grown over time, as has the premium for four-year college graduates. In 2014, this gap was 12 percent for women and 15 percent for men, although this group includes those who have earned short-term certificates who bring up the average (see Table).

Furthermore, noncompleters represent a large fraction of borrowers who struggle to repay their student debt, as documented in the study “A Crisis in Student Loans? How Changes in the Characteristics of Borrowers and in the Institutions They Attended Contributed to Rising Loan Defaults” (Brookings Papers on Economic Activity, Fall 2015). Despite the development of income-driven student loan repayment plans, which ensure that borrowers will not have to make monthly payments higher than a reasonable percentage of their incomes, borrowing money and paying for years for an education that does not pay off is a very real burden. Completing that education and building on it in the labor market is the starting point for a secure and satisfying life.

By necessity, college and university financial officers focus on the prices charged—both sticker prices and prices net of institutional grant aid. They should also focus on what students get for their investment and on why it is wise for them to work hard and make considerable sacrifices to take advantage of the opportunities offered. This means understanding the financial and nonfinancial returns to a college education. It means focusing on the high average returns without ignoring the variation in outcomes. And, it means providing the information and guidance students need to make sound decisions about their education and their future. No easy task, but an essential one.

SANDY BAUM is a senior fellow at the Urban Institute, Washington, D.C.