Liberal arts colleges today face game-changing challenges, such as a declining number of students, acute financial situations, intensifying competition, and pressure to keep academic offerings updated. Add to that the recent recession, which stressed flaws in nearly every institution’s business model. This near-fatal combination of factors forced colleges to wrestle with the essential strategic questions that for decades have pitted academic and social commitments against financial realities—and do so while operating under significant stress.

The severity of these collective problems led me to focus my dissertation (“The Endless Good Argument”) on investigating how small colleges make effective strategic choices that ultimately affect their institution’s current and future performance. The “endless good argument” is the necessary, ongoing discussion among all stakeholders that is critical to effective decision making.

While the president, senior staff, and boards of vulnerable small, private liberal arts colleges were all under pressure, sometimes uncoordinated in their actions, and ill-informed about critical details, certain schools succeeded despite all the pressure. The dissertation research set out to answer a series of questions about how institutions dealt with the enormous challenges, particularly declining enrollments, intensifying competition, and academic relevance during the financial upheaval of the recession.

My research identified four conclusions about life in the fragile world of small private institutions:

- Strategic planning has to be more than a plan.

- Board governance is crucial.

- The institution needs the right leader for the right time.

- Action is important, but execution will define you.

While my research chronicled and measured the effectiveness and outcomes of strategic choices made by leaders at three liberal arts colleges during the recession, this article will focus on only Sewanee: The University of the South, Sewanee, Tennessee.

Sewanee is prospering, while other liberal arts colleges and universities are flagging, because of the effectiveness of strategic choices made by the university’s leadership. The combination of an engaged board and suitable and strong institutional leadership committed to adhering to and acting on a viable strategic plan appears to have made the difference.

I’ll also draw some comparisons to Oglethorpe University, Atlanta, another small, private college that demonstrates similar strategic choices—and where I currently serve as the chief business officer.

Historic College, Futuristic Vision

In 1857, clergy and lay delegates from Episcopal dioceses throughout the South founded the University of the South. Located in Sewanee, Tennessee, the campus was slated for the western section of the Cumberland Plateau between Nashville and Chattanooga, encompassing nearly 10,000 acres donated by a local landowner and the Sewanee Mining Co. With construction scheduled to begin in 1860, the Civil War delayed the university’s opening until 1868, when nine students and four faculty members were in attendance.

Women were first admitted as full-time students in 1969; the university would grow to a peak of 1,500 students, evenly divided between men and women. Today, the campus encompasses 13,000 acres and includes the College of Arts and Sciences and the School of Theology.

Sewanee’s governance structure is dictated by its ownership and ongoing relationship with the Episcopal Church, 28 dioceses of which share ownership of the university and govern through a two-tiered system.

- The umbrella governing body is a board of trustees (150 members), most of whom are elected from these dioceses.

- The second tier is a board of regents (20 members), which acts as the executive board of trustees.

The chief executive officer for the institution is the vice chancellor and president. The chancellor is elected from among the bishops of the owner dioceses and serves as chair of the board of trustees and, along with the vice chancellor, is a member of the board of regents, ex officio.

Leadership legacy. In 2000, Joel Cunningham was named the 15th vice chancellor and president of the University of the South. During Cunningham’s tenure, he focused on extending the university’s reach and recognition. He went at this in several ways:

- Campus renovations would take precedence. All Saints’ Chapel, Gailor Hall, and St. Luke’s Hall were substantially renovated. New construction included Humphreys Hall (the first new residence hall in more than 30 years); Spencer Hall (a new science building); the Nabit Art Building; an addition to Snowden Hall (the forestry and geology building); and an architecturally striking new dining hall located in the middle of campus. The Snowden Hall project was a direct outgrowth of Sewanee’s strategic plan objective to be a national leader in environmental studies and sustainability.

- The university launched a capital campaign called “The Sewanee Call.” This campaign, which concluded in June 2008, raised $205 million, exceeding its $185 million goal. During Cunningham’s tenure, the campaign funded a little more than $60 million of the $76 million in Sewanee’s plant renovations and expansions.

- Cunningham supported various efforts to extend the reach and recognition of the university. “It was not so much to differentiate as to strengthen,” Cunningham said. He noted that Sewanee has a “central core of students that it attracts, so we wanted to build the recognition more widely.” This would be done through program extensions, such as the sustainability initiatives and facilities updates in what Cunningham referred to as a “weaving together or a quilting together of initiatives” that supported the key points of a strategic master plan.

To that end, plans called for Sewanee to grow its student base by becoming a more national, selective, and racially diverse university. At the time, 4.5 percent of the 1,400 undergraduates were black, 2 percent were Hispanic, and 2 percent were Asian Americans.

In addition, in 2005, in an effort to expand the brand, the university name was changed to Sewanee: The University of the South, with a decided emphasis on “Sewanee.” In an attempt to remove any stigma attached to the university, a number of physical symbols of the South were removed. The flags from southern states disappeared from the chapel. The ceremonial baton dedicated to a Confederate general who helped found the Ku Klux Klan was replaced. The effort to rid the school of its southern stigma had mixed results in increasing the diversity of the student population. In the fall of 2011, the student body population was 86 percent white, 3.9 percent black (a loss of .6 percent), 3.6 percent Hispanic (a gain of 1.6 percent) and 2 percent Asian (no gain or loss).

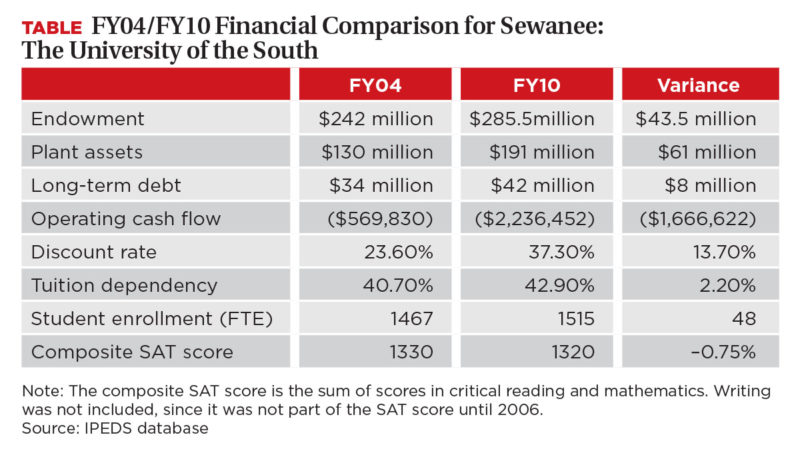

- Cunningham took a conservative approach to the management of the school’s finances. From 2004 until 2010, when Cunningham retired, this approach increased the financial stability of the university, which can be evidenced in the growth of endowment (increase of $43.5 million) and the addition of $61 million in plant assets (see table).

The institution, however, also began to see erosion in key indicators important to the admissions process. At the close of Cunningham’s tenure, the conversion rate of admitted to enrolled students dropped from 30 percent to 23 percent, 6 percent lower than that of its peers. Net tuition growth had declined steadily from 11 percent in 2004 to .65 percent in 2010, due primarily to an increase in the discount rate from 23.6 percent in 2004 to 37 percent in 2010.

The recession stressed Sewanee to a lesser degree than most universities because of the way the institution managed risk. Cunningham referred to risk as “an edge” to be approached with measured caution. When talking about how much risk an institution should take on, Cunningham commented that one of the hardest decisions a president has to make is in understanding “where that edge is and how close you are to it.” Fiscally sound policies based on accurately gauging risk enabled Sewanee to face difficult challenges during the recession and still “move the needle a little.” Cunningham referred to this as luck; in hindsight, it was a sound strategy.

A Bolder Plan

In 2010, the board of trustees elected John M. McCardell Jr. as the university’s 16th president and vice chancellor. McCardell had served as president of Middlebury College, Middlebury, Vermont, for six years prior to his arrival at Sewanee. Immediately, McCardell recognized two primary problems: Net tuition revenue growth had stalled, and, beyond the Southeast, few people knew about Sewanee.

Repercussions from the recession were inhibiting the school’s ability to grow net tuition revenue. The high tuition–high discount business model had worked at Sewanee for years. From the beginning of 2008 to the end of 2009, the percentage discount rate jumped from the mid-30s to the mid-40s. Due to a more cost-conscious consumer, revenue from rate hikes was being offset by increases in scholarships, and more scholarship aid was needed to attract the same number of students. The paradigm had shifted for Sewanee, and the value proposition that had worked for years needed to be changed.

McCardell also believed the university to be a “too well-kept secret.” He felt the school “needed to be better exposed” and was “better than it and many other people thought it was”—and he said so in his first public addresses. He envisioned a Sewanee that was national versus regional, and he would build programs and make changes to the university based on this vision.

While the name of the university was expanded in 2005 from “The University of the South” to “Sewanee: The University of the South,” McCardell believed it was still limiting. He said, “One of the first things I would need to confront was the name, the University of the South, and the Confederate history, which was still part of the place.”

On his first day in office, on July 1, 2010, McCardell asked in his invocation, “What does it mean to be the University of the South, and what South are we the university of?” At a number of later events, both public and private, he would substantiate his statement that “We once were but no longer are the University of the 1860 South, or the University of the 1920 South. They made us who we are, but we’re no longer that.”

Facing certain declining enrollment trends, stalled growth in net tuition revenue, the lack of diversity in the student body, and the lack of brand awareness beyond the region, McCardell proposed a bold new strategy—a significant reduction in tuition.

In February 2011, the university’s board of regents approved a 10 percent reduction in tuition and fees at the college. The price reduction would apply to tuition, fees, and room and board for the 2011–12 academic year; it represented a $4,600 overall reduction per student, per year. Sewanee projected that the drop in tuition would help it compete with other private colleges as well as with the public universities that were siphoning off a growing share of the students that Sewanee accepted.

The university’s leadership expected that a substantial portion of the financial impact from this decrease would be absorbed in reduced scholarships to its students. For FY12, the cost in net tuition from this cut was approximately $1.5 million, which was less than expected.

In December 2012, the school made yet another major announcement: It would guarantee flat tuition and room and board rates for four years for the college class entering the university the following fall. Overall, during the period studied, the university experienced tremendous growth in its endowment and plant assets, without adding much debt. The tuition reduction, however, took its toll on operating cash flow in 2011.

Oglethorpe’s Strategic Comeback

While the tactical choices differed, the story of Oglethorpe University is not unlike that of Sewanee, except in severity. Oglethorpe was financially hemorrhaging in 2005, and as a result placed on an accreditation warning by SACS (Southern Association of Colleges and Schools) in 2008.

Facing what would be a $4 million revenue shortfall, in 2005 the board of trustees voted to sell land to cover a significant operating budget deficit. The proceeds from the sale were quickly absorbed by ongoing operations. Trustees acted swiftly to hire a new president, one suited to tackle the financial challenges and move the university forward academically.

When I joined the staff as chief financial officer, SACS was placing the school on its second year of warning. None of us in the president’s cabinet anticipated the severity of the recession’s repercussions in combination with the SACS warnings. The dual dynamics forced us to look down instead of forward. Over the next three years, we significantly reduced expenses and aggressively worked to diversify our revenue streams.

While these were extreme circumstances, Oglethorpe is not unlike a host of other small liberal arts colleges that are underendowed and must struggle on an annual basis to balance their budgets. Fortunately, the sanction by SACS spurred all the stakeholders at Oglethorpe to focus on a remedy. Today, the budget is balanced, depreciation is covered, the endowment totals more than $20 million (from a low of $13.5 million in June 2009), and the current capital campaign has surpassed $40 million—including the largest individual and foundation gifts in the school’s history. The drivers that moved Sewanee forward—an engaged board, the right leadership, and commitment to act in accordance with a set of rules and a plan—had held true for Oglethorpe.

In the fall of 2013, we opened the Turner Lynch Campus Center on campus. The $15.2 million, 49,000-square-foot center, fully funded by donations, is serving to engage students, faculty, and the community. Our residential population has increased 50 percent over the past five years, and a new residential project is under way. The financial model—a joint partnership with a national developer—will not incur debt and will substantially increase our endowment.

Our 2020 strategic plan commits resources to upgrading our campus and our curriculum, while adhering to financially conservative, yet market-ready, policies.

Telling Conclusions

Taking all these actions and results into consideration, it’s clear that the prevailing business model at many schools was severely battered during the recession. My original study set out to shed light on the efforts that made the most positive differences, using four research questions:

- What strategies were used to manage the effects of the recession?

- What impact did leadership make?

- Were the outcomes different? If so, was this as a result of the strategy, or the implementation, or both?

- What lessons can be learned from the study that will provide guidance for leaders of other institutions?

Relating these questions to the Sewanee experience led then to the conclusions noted earlier.

Strategic planning has to be more than the plan. As was the case with most other institutions, Sewanee’s leaders understood that in a highly competitive market, they could not stand still—particularly when the recession intensified the situation. A transition in leadership at Sewanee two years into the recession shifted the university to a bold pricing plan from a fairly conservative strategy that had started to fail. Leaders had a clear understanding of their financial challenges and strengths, enabling them to act.

Sewanee had a strategic plan in place at the time of the recession. Yet, it did not initially react to or make changes to that plan. To be fair, the full impact of the recession did not become apparent all at once, but unfolded in stages—first the impact on endowments, followed by cutbacks in state funding, then tightened lending that made it hard for parents and students to borrow. When unemployment began to skyrocket, the university saw parental need increasing, and began to offer more unfunded scholarships in order to retain students. By the time the full fallout became evident, institutions were in reactive mode rather than in planning mode.

For Sewanee and many other colleges and universities, existing strategic plans did not take into account the possible impact of a recession. Hence, institution leaders began to take advantage of unexpected opportunities where they could find them. While these on-the-fly strategies were sometimes effective, their success or failure came not from the ideas themselves but from the execution and discipline applied to each situation.

As part of the Sewanee governance culture, McCardell convened a committee of faculty and staff to assess a number of different “what if?” scenarios, based on empirical data that looked at who the university’s customers were and what they needed. The group also took into account an analysis of the competition, taking related data, projecting the worst-case financial situation, and deciding whether or not the university could absorb the impact. This analysis was then presented to the executive committee of the board and was scrubbed again, until everyone felt as if every rock had been turned over and they were all comfortable with their strategic choice.

In the end, that worst case never materialized, but the institution was prepared for it. McCardell showed strategic discipline by recognizing that the university had priced itself out of the market, and he had the discipline to act upon that fact.

Board governance is crucial. Leadership has a profound influence over the mission, strategies, structure, and culture of an institution. Liberal arts institutions face enormous challenges and are often underendowed and underresourced. Any combination of poor leadership, unwise strategies, or badly executed plans can bury them quickly.

Ultimately, the leadership at most institutions resides with the board that hires the president to handle the day-to-day operations of running the institution and act on the board’s behalf. This one act—and its subsequent impact on the institution—makes board governance a crucial factor.

The institution needs the right leader for the right time. Board members and search committees are charged with trying to match the skills of a future president to the needs of the institution at a given point in time. And, while virtually all new presidents bring particular skills and experiences to the job, the ultimate success of that president has more to do with his or her timing at the institution than with any abstract set of skills or experiences. So, for Sewanee, the board transitioned from the financially conservative Cunningham to the more aggressive McCardell.

In this case, McCardell’s bold pricing strategy was built on Cunningham’s strong recession-proof balance sheet—a solid example of the right person for the right time, and proof that leadership really does matter.

Action is important, but execution will define you. When the recession hit, the carryover of well-disciplined management was clearly one of the main factors in determining the different outcomes achieved by various institutions. Cunningham claimed that it was just “dumb luck” that his conservative fiscal approach to running a university had positioned Sewanee to take on the recession with minimal impact. But, was it really about luck—or good management? He built more than $70 million in plant assets during his tenure at Sewanee while taking on only $8 million in additional debt—and increased net tuition by $6 million. He took action, in a very disciplined and collegial way.

McCardell has built upon this legacy, and since 2011, Sewanee has seen a 5 percent increase in enrollment, with 1,586 students. While the objective to diversify the student population has not materialized, the net tuition grew by $2.08 million or 6 percent, primarily due to a 6.5 percent drop in discount rate. Cash flow from operations swung dramatically from a loss to a $9.4 million gain.

From a risk perspective, a key difference in the two leaders is in their approach to debt. Cunningham relied heavily on fundraising, while McCardell has so far used debt to complete $21.9 million in campus enhancements. Different times require different leaders and different financial tools.

MICHAEL HORAN is vice president of business and finance, Oglethorpe University, Atlanta.