While we have all repeatedly heard and tried to act upon Jim Collins’ admonition in Good to Great (HarperBusiness, 2001) to “get the right people on the bus” and make sure they are “in the right seats,” we must also deal with the reality that hiring qualified, talented employees is an imperfect process. In fact, in my experience, hiring the right talent is among the most challenging tasks for higher education administrators.

In recent years, higher education has been in a state of flux due to enrollment and demographic trends, declining state support, and long-term financial uncertainty. To complicate matters, recent studies by NACUBO and TIAA-CREF indicate that many of the 40 to 60 percent of higher education business officers indicating that they planned to retire over the next four to five years have already begun that exodus.

With high levels of turnover comes a loss of institutional memory, making it imperative that we recruit effectively. New hires will have to hit the ground running and deal with immediate issues and needs.

Understanding and utilizing best practices for searching and filling professional positions will greatly increase the likelihood of success in that effort. While most higher education institutions use a search process, the results can vary widely depending upon the level of conformity to best practices. This article will provide an overview of the Indiana University Southeast, New Albany, search process, which has yielded effective results and successful outcomes for the institution during a time of leadership transition and reorganization.

The Foundation: Established Procedures

Institutional policies and procedures are the foundation of any best-practice recruitment program. IU Southeast publishes the Academic-Professional Recruitment & Search Guide (www.ius.edu/diversity/files/best-practices.pdf), which is an excellent resource for search committee chairs and members. The guide includes search process flow charts and sections that provide guidance on each step of the recruitment and search process.

IU Southeast’s office of equity and diversity maintains the guide, trains search committees, and reviews all full-time applicant materials. This office also provides approval at three critical steps to ensure compliance with state, federal, and institutional requirements. Specifically, the office provides approval to advertise, interview, and extend offers.

An Eight-Step Sequence

We have found that adhering to the following process is a proven method for recruiting and identifying the best candidates to fill open positions in our various departments on campus.

Position review and approval. When a job opening becomes available or a new position is created, prior to advertising the opportunity, the unit hiring manager reviews the position description to ensure that it is accurate and up-to-date. This is an important step in the search process, as position descriptions are likely to become outdated over time, because of changes in technology, processes, and systems—and especially with the growth of shared services over the past five years.

This is also a good opportunity to consider alternatives to filling the position and potential reorganizational initiatives. A justification write-up (see the sidebar, “Indiana University Southeast Position Justification Form”) asks: (1) What alternatives have been considered to maintain existing service levels? and (2) Can the responsibilities be reassigned or restructured? Reorganizational decisions could occur prior to a recruitment packet being prepared (the form is supposed to facilitate that thought process), or after the packet is sent to the budget committee.

After the position description review, our human resources (HR) office will check the position classification and salary. The position is then “packaged” and routed to the campus budget committee, which meets every two weeks to discuss budgetary matters, including review and approval of requests to fill open positions. The budget committee comprises the chancellor and the respective vice chancellors for academic affairs, administrative affairs, advancement, and enrollment management/student affairs. The position packet includes a routing cover sheet, the position description, a justification write-up, and an organizational chart for the school or department. Cabinet review and approval of requests to fill vacant positions was highlighted by our accrediting body in 2010 as a best practice.

Advertising the position. Once the campus cabinet approves the position to be filled, the unit hiring manager will collaborate with HR to determine the best venues for advertising and promoting the position. To use a fishing analogy, the goal is to drop the line in the body of water that will yield the most qualified and diverse pool of applicants. Recruiting prospective applicants who are not actively looking for a new position is just as important as attracting applicants who are actively working the job market.

At IU Southeast, we have had the greatest success by posting open positions on professional and higher education websites with the greatest reach, such as those of HigherEdJobs.com, UniversityJobs.com, LinkedIn.com, and the Chronicle of Higher Education (https://careers.chronicle.com). Professional association-specific sites, such as NACUBO, NACAS, NASPA, APPA, AFP, CASE, and ACUI, extend the reach to targeted groups. A recent professional hire told us that he was not actively looking for a job change but saw the posting on a professional networking website and made the decision to apply for the position. He quickly emerged as a finalist and was eventually selected for the position.

Assembling the search committee. The goal of the search committee is to screen applicants and recommend candidates who are deemed to be acceptable for hiring, based upon their credentials, performance in the interview process, and feedback obtained from the campus community. Our recruitment and search guide states that “the membership of a search committee should reflect the diversity of the campus.” The committee should also include members who have an understanding of the duties and responsibilities of the position being filled. One member is appointed as the “affirmative action monitor,” who ensures that the search process and the committee’s actions are equitable; bias-free; and consistent with applicable employment policies, laws, and regulations.

The nature and level of the position being filled determines the size of the search committee. For example, a search committee for a senior leadership position might have eight members to achieve an appropriate level of representation. A search committee for a non-director professional position may require only three members to conduct an effective search. Our search guide requires at least three members, including the committee chair. The goal is for the size of the committee to be sufficient to provide diverse representation, thoughts, and perspectives without becoming too large for scheduling and discussion purposes.

It is important to note that representation can also be achieved through the on-campus interview schedule. Remember that the goal of the search committee is to screen applicants and recommend viable candidates. If it appears that the search committee is getting too large, consider giving a constituent or stakeholder dedicated time during the on-campus interview rather than a seat on the search committee.

Initial screening. Our campus HR office will pre-screen applicants to ensure that they meet minimum qualifications, and will then refer qualified applicants to the committee for further consideration. It is then the job of each committee member to review each applicant’s materials and identify preferred candidates for phone interviews.

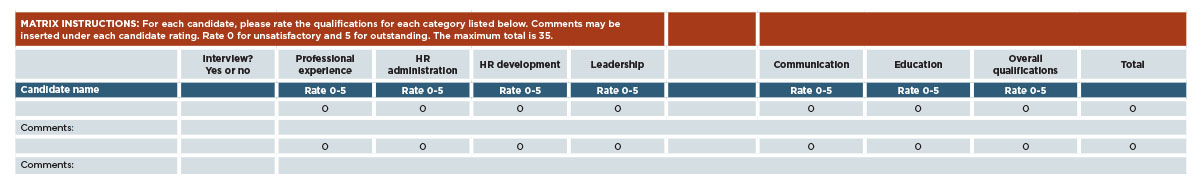

To facilitate this task, we provide each search committee member with an evaluation matrix that rates each applicant on a scale of 0 (weak) to 5 (strong) in seven categories. Six of the categories are position-specific (relying heavily on the position description), and the seventh category is “overall demonstration of qualifications.” The total rating for each candidate is intended to be used only to prioritize the applicants for group discussion purposes. (See sidebar, “IU Southeast Director of Human Resources Candidate Matrix.”)

We ask committee members to rate each applicant consistently, then identify the top preferences for applicants to be invited for phone interviews. We also ask committee members to keep their ratings confidential. Rarely do two committee members arrive at the same rating for the same applicant, and we do not want the discussion to stray to a debate of numerical ratings. The evaluation matrix is a tool that provides structure to a subjective process, assisting the committee in identifying top applicants for phone interviews.

After committee members have reviewed the materials for all referred applicants, the search committee reconvenes and the group discusses each applicant in the same order in which he or she appeared in our online application system (to avoid any type of perceived intentional ordering of the applicants). This usually takes two to three passes. The first pass is “consider further, or not” and usually eliminates well over half of the applicants. This is generally due to the high number of individuals who use a “shotgun” approach in the job search process, rather than targeting positions for which they are well suited. Subsequent passes will lead the search committee to a smaller group of candidates for phone interviews. The general rule of thumb is to identify six to 10 candidates for phone interviews for a given position.

Phone interviews. Telephone conversations are a highly efficient, highly effective means of identifying candidates for on-campus interviews. Application materials only provide a two-dimensional view of the applicant. The phone interview provides the third dimension. It is very tempting to bypass the phone interview process and attempt to identify candidates for on-campus interviews for purposes of expediency.

Bypassing the phone interview step may result in bringing candidates to campus that would not have been chosen after a weak phone interview. A mistake of this magnitude will add time to the search process and result in unnecessary travel reimbursements. Phone interviews are an essential component of a best-practice search and screen process.

We schedule phone interviews for 30 minutes each, which is an appropriate amount of time for 10 questions. During our introduction to the interview, we tell candidates that we would like to ask 10 questions over the next 30 minutes, which leaves approximately three minutes to answer each question.

This does not leave time for candidate questions. We explain that we will provide ample time for candidates to ask questions during the on-campus interview should the committee extend an invitation to meet face-to-face. This framework provides an opportunity for candidates to demonstrate that they heard our instructions and can manage their time accordingly. Reminding a candidate 10 minutes into the interview that there are still nine questions remaining may become a determining factor for candidates who are “on the bubble.”

The first question is the same for all searches. It is a simple question that is intended to determine the amount of time the applicant has spent researching the campus and preparing for the phone interview: “What have you learned about our institution in preparing for this interview?” We have seen candidates rise and fall on this introductory question. For example, an excellent response would include information learned from the institution’s website, press releases, or strategic plan. Candidates who have gathered an appropriate amount of intelligence about our campus immediately differentiate themselves from other applicants.

The remaining nine questions for the phone interview gauge the applicant’s suitability and preparedness for an on-campus interview. The questions are intended to highlight each applicant’s (1) professional knowledge, experience, and accomplishments; (2) vision for the position or function; and (3) leadership style.

It is important to solicit interview questions from the search committee. Questions that are not selected for the phone interview are placed in a question bank for the on-campus interview. (See Figure 1 for a list of possible questions.)

On-campus interviews. After screeners have completed all phone interviews, the search committee will discuss each candidate’s performance during the phone interview and will agree upon the candidates that will be invited for on-campus interviews. Bringing three to four candidates for on-campus interviews is a good rule of thumb.

The goal of the on-campus interview is to get the candidates in front of as many stakeholders and constituents as possible. A typical on-campus interview schedule for a director or senior administrator is illustrated in Figure 2.

The open session is intentionally scheduled in the afternoon, after most of the interview sessions have occurred. We like to see how the candidate performs in a setting that is typical of the workday, observing whether or not the candidate has the stamina to make it through the entire day.

For the open session, we ask candidates to deliver a 10- or 15-minute presentation that summarizes their vision for the department or division that they will lead. The open session provides another critical step in the process by providing an opportunity to see how the candidate communicates, presents, listens, and interacts with a small cross section of the campus community. Does the candidate attempt to use humor? Is the humor appropriate for the audience? Does the candidate make a statement or provide a visual that connects with the audience or vice versa?

Feedback forms. One of the most important components of a best-practice search process is the use of feedback forms. We use a very simple format that asks participants for feedback in four areas: candidate strengths, candidate weaknesses, overall comments, and the level of endorsement indicated by checking the respective box for “recommend,” “recommend with reservation,” or “do not recommend.”

Throughout every step of the interview process, we remind participants of the importance of the feedback forms, which allow every voice to be heard. An engaged campus community will be very discerning when it comes to evaluating interview performance and identifying candidate strengths and weaknesses. The key to engagement is maintaining open and continuous communication throughout the search process.

Timing is also an important factor. For example, an open session will be better attended by faculty when the campus is in session rather than before or after the semester starts or ends.

We will usually give our campus community one week after the date of the last on-campus interview to submit feedback forms for all candidates. Many participants will wait and submit their forms altogether, desiring to see all candidates before indicating a level of endorsement for a particular applicant. As long as we eventually obtain all the forms, we will take them individually or as a group.

After all feedback forms are submitted, the search committee chair will review the forms, summarize the overall impressions from the campus community, and provide this information to the search committee for deliberation.

Search committee recommendation. The chair shares copies of the feedback forms with all committee members, along with summary reports and tabulations. At this point in the process, the search committee has the benefit of phone and on-campus interview observations and feedback from a broad range of constituents and stakeholders. It is now the search committee’s job to recommend finalists for consideration. At a minimum, we want to see a summary of strengths and weaknesses of each candidate and the level of endorsement (recommend, recommend with reservation, or do not recommend) made by committee members.

Search committee chairs must ensure that each member has an opportunity to share his or her impressions of each candidate and that discussions remain open and balanced. After a lengthy investment of time in the process, it is natural for committee members to feel strongly about a candidate they favor or disfavor. Each committee member will have a different view of the candidates, and participatory, respectful discussion is critical to achieving group consensus.

It is important for search committee chairs to listen to the discussion, manage “floor time,” and encourage consensus through validating questions such as: “I am hearing a ‘recommend’ for candidates A and B and a ‘recommend with reservation’ for candidate C. Are we all in agreement so far?”

Search committees may be tempted to select the candidate. Once again, the goal of the search committee is to screen applicants and recommend viable candidates at the completion of a robust process. The hiring manager will make the final selection based upon strategic goals, recommendations from the search committee, and feedback from our campus community.

Upfront Investment Pays

An effective search process requires ample budgetary support. The most common search expenses include advertising, professional association posting fees, and candidate travel expenses (lodging, meals, and transportation). The cost of a search for a professional position can range anywhere from $5,000 on the low end to $10,000 or more, depending upon the position level.

While this may seem high, especially when budgets are tight, it is an investment in the organization’s future. An appropriately funded search will increase the likelihood of success. In addition, the annual operating budget should include sufficient funding for multiple searches.

Keep in mind, too, that making a bad hire can cost thousands of dollars, in addition to the nonfinancial damage that may result. According to a 2015 survey by global staffing firm Robert Half, the biggest cost of a bad hire may, in fact, go way beyond financial considerations. The majority of the 2,100 chief financial officers surveyed were most concerned about degraded staff morale (39 percent) and a drop in productivity (34 percent). Commenting on the survey, Greg Scileppi, president of international staffing operations at Robert Half, said: “A bad hiring decision can often cause a negative ripple effect through the organization. Hiring a bad fit or someone who lacks the skills needed to perform well has the potential to leave good employees with the burden of damage control, whether it be extra work or redoing work that wasn’t completed correctly the first time. The added pressure on top performers could put employers at risk of losing them, too.”

Hiring professional employees is an imperfect, subjective process. By following a structured process that is applied consistently to all applicants, search committees will greatly increase the likelihood of getting “the right people on the bus” and “in the right seats” to achieve the institution’s vision and strategy.

DANA C. WAVLE is vice chancellor for administration and finance, Indiana University Southeast, New Albany. DARLENE P. YOUNG, director of staff equity and diversity, and RAYMOND A. KLEIN, director of human resources, Indiana University Southeast, contributed to this article.