If you’ve ever had a list of movable assets that didn’t fully resemble the equipment actually on hand, you’ll understand the situation at the University of Notre Dame, Notre Dame, Ind., some seven years ago.

At the time, the controller’s office relied on department personnel to conduct their own inventory but didn’t have the resources to follow up and ensure accuracy. This had implications whenever internal audit performed a departmental audit or a federal agency performed a desk audit. Although we never had major issues arise, the process seemed more challenging than it needed to be. For example, it often took a lot of time for department personnel to confirm pieces of equipment because the asset descriptions—usually taken straight from the purchase orders—didn’t make sense; they were either too technical or too vague. In addition, when preparing for the audits, the departments often had difficulty finding equipment that had been relocated, or they would discover some assets that had never been tagged or simply had been disposed of.

With a growing research presence on campus, we anticipated the addition of new equipment as well as increased collaboration among researchers—which could mean even more equipment relocations. All these factors contributed to the need to take better control over the equipment inventory. Above all, we wanted to make the process more manageable—for researchers and professors, department personnel, and accounting staff alike.

Technology to the Rescue

Anecdotally, in talking with colleagues at other institutions, we found that homegrown inventory processes tended to be the norm—and we were unable to identify one that we considered at best-practice level. Both our leadership and our IT department encouraged us to look at outside vendors instead of trying to create internal software to interface with our Banner accounting software.

Our research led us to issue an RFP for radio frequency identification technology. RFID uses low-power radio waves to communicate between a reader—a network-connected device with an antenna—and a tag containing an integrated circuit and small aerial. Each tag is programmed with an identification number that is linked to external software, which contains the assets records and is interfaced with our accounting software. The asset records are also accessible on the reader for use when performing our inventory.

RFID tags are probably best known as the identification “chips” that veterinarians implant in dogs and cats. Other popular uses are in library books for electronic checkout and on car windshields to facilitate electronic toll collection. Typically, inventory tags are encased in paper or plastic and have a peel-and-stick backing. The lowest cost tags are called “passive,” because they have no power source of their own. Passive tags must be in fairly close proximity to the reader so that it can activate them. “Active” tags, on the other hand, are powered by internal batteries and can be read at greater distances (usually up to 100 feet). Active tags are typically used on more expensive items or those that are difficult to access. In addition, special tags are usually needed for assets that contain a lot of metal, which can interfere with the tag’s internal antenna.

The big advantage of RFID is that one reading device can read numerous tags at once just by being close to the tagged items—and the tags don’t have to be visible. In contrast, a bar-code inventory system requires direct access to every tag and can scan only one item at a time.

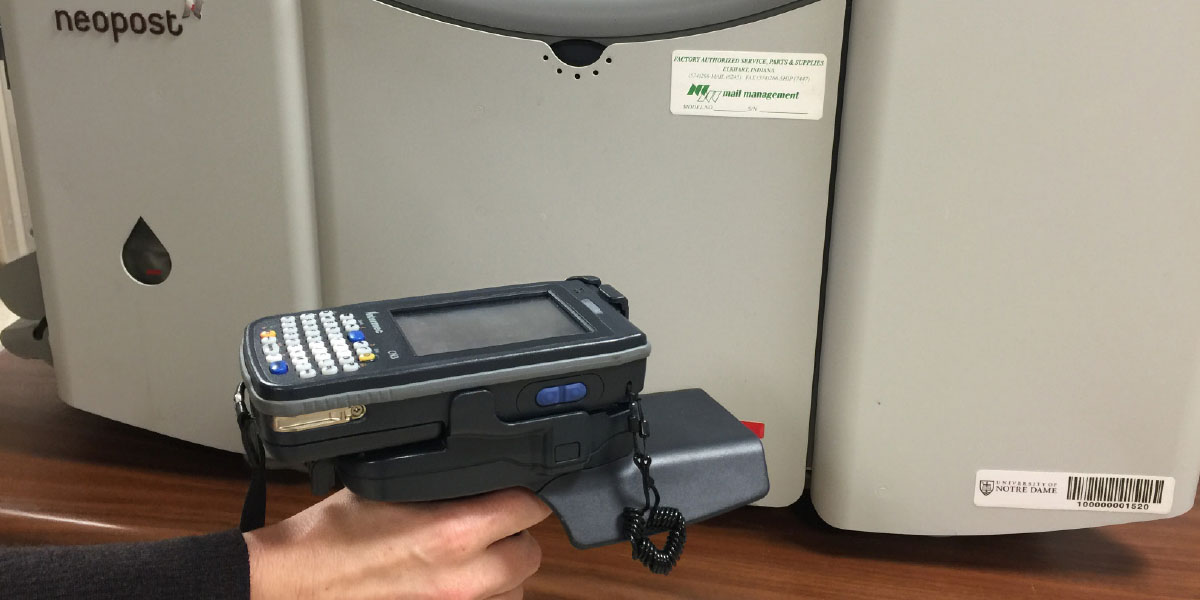

Conducting an inventory with the RFID reader—in our case, a handheld device that looks somewhat like a radar gun—required the following:

- We download to the reader all the expected assets in a particular location.

- After we activate the reader and survey the location for a few minutes, the reader will confirm what we expected to find, as well as identify any exceptions—such as an item that is listed but missing or one that is present but assigned to a different location.

- Within minutes we can do the reconciliation on site; the reader transmits the confirmed or corrected information back to our software system via Wi-Fi, automatically updating our records.

If this sounds like an efficient way to inventory assets, it is. On the road to that result, however, we encountered several delays and detours that required us to do some rethinking and put our project management skills to the test.

Coming Clean

Early in 2011, Notre Dame selected a vendor to supply the RFID hardware, tags, and hosted software and moved into a 10-month pre-implementation phase. During this time, we completed our last “facilitated” inventory with department personnel and worked with the RFID vendor to customize the software for our use and synchronize it with Banner. We also had to reorganize and update the information on each asset in preparation for re-tagging.

Historically, the primary way we had tracked equipment in our accounting system was by its funding source. This made sense when we had to distribute inventory lists to equipment “owners” to perform the inventory. But we quickly discovered the shortfalls of this approach when performing the inventory ourselves. For example, equipment funded by a particular dean’s office might actually be used in a laboratory across campus. With the move to an RFID system, we decided that the more data elements per piece of equipment, the better. So we added several new fields in our accounting software, including the department responsible for safeguarding the asset, the inventory contact (or asset custodian), and building and room numbers.

This inventory cleanup proved time-consuming. We had to scour our records to:

- Find out who initially used each asset.

- Determine if the person was still at the university.

- Confirm the asset’s current location.

- Rewrite the asset description for easier identification.

Along the way, we also discovered that many departments had disposed of older assets, but did not notify us.

January 2012 marked the start of an 18-month implementation phase. Our goal was to apply an RFID tag to every asset by July 1, 2013, so that we could start the new fiscal year with an accurate inventory. In FY12 alone, we registered nearly 900 disposals of assets that had been fully depreciated. To assist with the implementation, we also hired additional staff members, who were detail-oriented, personable, and organized—the traits needed for establishing and building ongoing relationships with department personnel in charge of inventory.

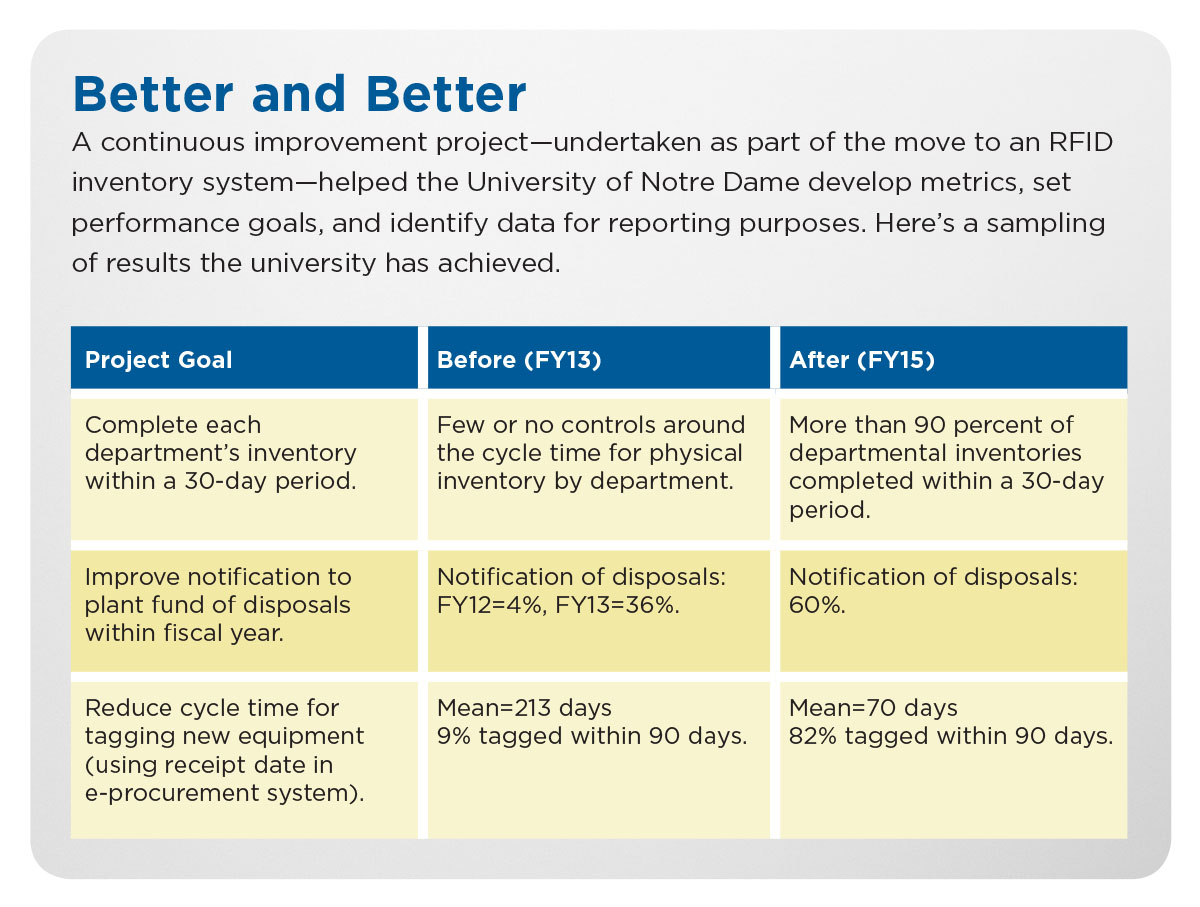

First to be tagged were the pieces of equipment funded by federal grants, followed by assets in other areas. A few months into the implementation phase, we initiated a Six Sigma green belt project related to the RFID system. At this point, we realized that we had taken a backward approach to improving inventory control: We had identified RFID as the solution without spending much time understanding what the problem really was. We had focused more on the end result rather than thinking through what was causing the problems in the first place.

With the assistance of Notre Dame’s continuous improvement department, we looked at the data on hand, reviewed the processes in place, and applied the voice of the customer to inventory control in general. An internal survey conducted as part of the green belt project helped identify root causes and provided valuable baseline data. The survey revealed, for instance, that few respondents were familiar with the proper disposal notification process. Many did not know where to find the disposal forms or even whom to contact with any questions about inventory.

The continuous improvement initiative also led to a modification of our e-procurement process. The system already alerted the controller’s office whenever a department purchased a piece of equipment above a certain dollar threshold or under a capital account code, but personal follow-up was still necessary. Now, the e-procurement system gathers more data about new assets at the time of purchase. If, for example, a purchase order contains multiple items, the purchaser is asked to identify any line items that work dependently as one system, so that they can be capitalized together in the inventory system. The purchaser is also asked to provide an understandable item description and the name of the person—not necessarily the same as the purchaser—to contact about applying the inventory tag.

Centralized and Continual

Notre Dame’s inventory control system has changed dramatically in the last few years, and not just because of the introduction of RFID technology. In fact, the biggest change is that we’ve centralized the inventory process and established closer relationships with departments.

We used to send the inventory identification tags to department personnel to affix, but many of those tags never made it onto equipment. Now, members of the controller’s office plant fund team affix the tags, usually within 90 days of the equipment’s arrival on campus (leaving time to ensure full payment is made). In the past, department personnel had the responsibility of double checking physical inventory against the inventory record provided by the controller’s office. Now, a member of the plant fund team visits each department and uses the RFID reader to verify an item’s existence and location. We’ve found that one team member can inventory about 75 items per hour using the RFID scanner.

The team’s visits to departments occur almost year-round, contributing to a perpetual inventory approach. After first surveying the 15 departments with the most pieces of equipment, to determine their preferences, we developed an inventory calendar that ensures every department is inventoried at least once every two years. The aerospace engineering department, for example, selected October, while the biology department went with May. With about 5,000 pieces of equipment in Notre Dame’s inventory, the schedule is a manageable amount of work, spread across three full-time staff and one student employee. Performing inventory requires a reasonable amount of work to integrate the process with the team’s other accounting duties, which represent 50 percent of our time. Typically, we don’t schedule inventories for July and August, when we’re busy with fiscal-year end.

Here are some lessons learned from Notre Dame’s implementation of RFID.

Ground your expectations in reality. Initially, we had visions of simply walking down a hallway with the RFID reader in hand and not having to involve departments in the physical inventory process. The signals emitted by most tags, however, aren’t strong enough to be picked up through walls. In most cases, the reader has to be within five to 10 feet of an item to register its information. In addition, we often need the department’s help to reconcile inventory results, locate equipment that has been moved, or identify pieces of equipment that have been combined to form a single system.

Another reality: You’ll need a workaround in your system for any items too small, too fragile, or simply inaccessible for tagging at all. Other items—particularly food service items and landscape equipment that tends to be power-washed—will require frequent re-tagging.

Don’t over-engineer the process. With the switch to RFID, we decided to use technology for all steps of the inventory process, including disposal notifications. We developed an interactive electronic form to flow automatically from one person in the approval process to the next. After implementing the form, however, disposal notifications continued to lag. As a consequence, most disposals were still being identified during the physical inventory process.

Far more important to us than the notification method used was learning that an asset no longer existed. So we took a step back from the all-electronic approach to give people the option of filing a simplified disposal notification form online or via hard copy. With this change in approach, disposal notifications increased markedly (see “Better and Better” sidebar on page 33) and time spent on processing forms has decreased.

Build solid campus relationships. Each member of the plant fund team has assigned departments for inventory purposes, giving each department a designated contact for inventory questions and disposal notifications. Applying inventory tags to new equipment provides staff with additional opportunities for interaction outside of the biennial inventory cycle. We’ve also forged strong working relationships with Notre Dame’s research accounting group and office of research, to ensure lab managers and professors understand the inventory system.

The departments with the most activity and largest number of assets receive additional communications. Each April, for example, we send an inventory list to those departments and ask about recent disposals to put on the books before year-end.

Strengthening campus relationships has been an added benefit of reinventing our inventory system. Our original goal wasn’t to save money; primarily, we wanted to have greater control and more information on our assets, and reduce risk. Introducing process improvements as well as RFID technology delivered all three.

SHERI CHEEK is plant fund program manager and JASON LITTLE is associate controller, accounting and financial services, University of Notre Dame, Notre Dame, Ind.