Every employee search can be embraced as an opportunity to hire a potential leader, as even technical or largely transactional positions require keeping future needs in sight. By identifying talent early, grooming that potential with special assignments, providing mentoring and leadership development, and then promoting employees when they are ready, employers will build employee loyalty and engagement, as well as improve institutional resiliency and capacity for succession.

Because recruiting and hiring are among the most impactful processes an organization can engage in, efforts to attract the best possible candidates should receive more than cursory attention. Most standard search processes remain largely focused on filling current needs rather than identifying the potential of an applicant to transform a given role. Contributing to this challenge are the limitations of the traditional position description, which typically predefines a role, thereby restricting the pool of potential talent.

Beware of Restrictive Descriptions

Transforming your organization’s hiring process begins with rethinking how you describe your employment opportunities. The position description is standard fare for every hire, and these job overviews can accomplish many good things, such as clarifying responsibilities, defining reporting structures, addressing compliance concerns, mitigating employment law liabilities, and creating the framework for candidate selection.

Internally, position descriptions are often the starting place for conceptualizing a role. That said, too often these descriptions are exceedingly linear in nature and fail to account for an individual’s specific soft skills and motivations beyond prescribed requirements.

Ideally, position descriptions should not anchor or limit the search but instead leave enough latitude to seize any opportunity to hire talent, no matter where it presents itself. A simple starting point is to replace required qualifications with preferred qualifications, where practical to do so. This step helps you keep from overlooking those individuals who do not possess the typical experience you seek, but still have the skills and abilities needed to complete required tasks and grow both into and beyond the position.

You can start this process of revamping employment descriptions by questioning assumptions about a given position and its often arbitrary requirements. For example, why does a position require five years of relevant experience instead of two or three years, or even none? Experience requirements inherently limit your pool of “qualified” candidates, excluding those candidates who haven’t yet had an opportunity to demonstrate their potential in current or previous roles.

Likewise, could relevant experience include nontraditional sources—for instance, experience with military intelligence instead of white-collar criminology for a forensics job? Is a degree in a specific field really required, or could a credential in cognitive science be as valuable as a computer science degree for a business intelligence job? Try to avoid typecasting, and instead identify underlying needs. Every position will have specific requirements, but deliberately expanding your thinking about the multiple ways a candidate can acquire the knowledge, skills, and abilities needed to be successful will broaden your candidate pool and may turn up promising talent.

Consider the description for a marketing position that establishes education requirements based on demonstrated mastery rather than the traditional go-to degree and a “years of experience” requirement. Instead of calling for “a bachelor’s degree in marketing and five years of related experience,” the job description could suggest “a bachelor’s degree or demonstrated mastery in leading successful marketing campaigns.”

Clearly, each position vacancy in your organization requires careful application of this idea. If, for instance, a CPA is required, you may not have ample latitude to accept someone without that specific training and certification. However, other professional certifications—such as a certified management accountant or a certified government financial manager—may serve the same need, and accepting more than one option may invite a broader pool of candidates to apply. The bottom line is that a position description should not be a predefined picture of who you’re looking for. Instead, it should be broad enough to allow multiple archetypes to emerge.

Identify Ideal Attributes

Listing desirable attributes in a job description can free potential candidates to apply based on their personality strengths. For instance, indicating that you are looking for “a person who is calm under pressure and can rise to the occasion when needed, but who can share the spotlight with others” signals to applicants that you know the complexity of the role requires more than simply checking the appropriate boxes of prior experience.

Loosening the constraints of a position description has the added benefit of diversifying your candidate pool. As noted by a study in The Confidence Code: The Science and Art of Self-Assurance—What Women Should Know (HarperBusiness, 2014) by Katty Kay and Claire Shipman, many women tend to apply for jobs only when they meet 100 percent of required qualifications. Broadening the way job descriptions are phrased can help prevent potential candidates from selecting themselves out of the process from the start.

While a position description of some sort may be necessary, it should not weed out potentially great hires in exchange for a candidate who fits the prescribed billing perfectly. Even “perfect” candidates need training once hired, often multiple times—first to cover their initial job duties and later if the needs of their roles change. Someone with strong soft skills who can adapt well may even surpass someone who initially looks better on paper, especially if the position changes down the road.

Hiring is always a balance between finding someone to meet today’s needs and the long-term potential of the candidate and position. Each situation and supervisor will have a different tolerance for which need is greater. Our advice is to openly question this need before you post the position, since this will inevitably shape what you post and the candidates you attract.

Look Beyond Current Needs

To secure the best people for the long term, leaders must actively be on the lookout for talent to fill current and future needs. One good example comes from a recent hire at our own school—the University of Arizona, Tucson. The vacancy was for a process-oriented position involving personnel transactions. The search process narrowed the applicant pool to two qualified candidates. When interviewed, one candidate stood out because of her experience with systems and processes; the second candidate stood out because of her big-picture insight. A typical search would have resulted in giving the first candidate the position and wishing the second candidate well.

Instead, leadership identified an opportunity to hire an HR strategist—a position that had not yet been posted but was being conceptualized. This became a serendipitous opportunity to hire two superstars and was a win-win for both the candidates and for the organization. This positive outcome was a direct result of the facts that leadership was on the lookout for talent and the position description was broad enough to capture multiple types of people in the search net.

Rethink Your Process

Even the most reflective, inclusive, and open-minded of us suffer from biases and unconscious prejudgments, potentially obscuring a treasure that’s right in front of us. Too often, these biases can creep into the position description as well. Instead of starting with an announcement that describes your need to meet a set of activities and accomplishments, consider writing a potential description first. Developing a potential description is, in fact, a visioning exercise that can help you avoid jumping to a hiring solution before engaging in broad thinking about your actual needs.

For instance, consider these questions to help you identify what you’re looking for:

- What are the necessary psychometric skills for this role (e.g., inquisitive, resourceful, emotionally intelligent, team-oriented, analytical, independent)?

- Who will this person interact with, and what is necessary for the individual’s interpersonal success?

- Where could a successful employee in this position naturally progress to within the organization?

- What is the value this person offers the organization, and who will be his or her natural allies?

- Are there challenges that will require certain abilities from the candidate (i.e., strategic thinking), or does the position require tactical thinking only?

- Who is the archetypal “perfect person” for this position and why?

- What did this archetype look and act like before becoming a superstar?

- What kinds of mentorship and coaching might be necessary to support the finalist’s progress?

When writing a potential job description, it may be helpful to pull in colleagues outside of the open position’s direct field because they lack the biases that come from knowing the typical job qualifications. It also helps to partner with others who are able to look past routine tasks and instead focus on the underlying skills, knowledge, and abilities required to succeed in the job. As part of this visioning process, consider what questions or short problem-solving exercises you could ask a candidate to engage in as part of the interview, and determine how you might identify a candidate’s abilities without relying on his or her prior experience.

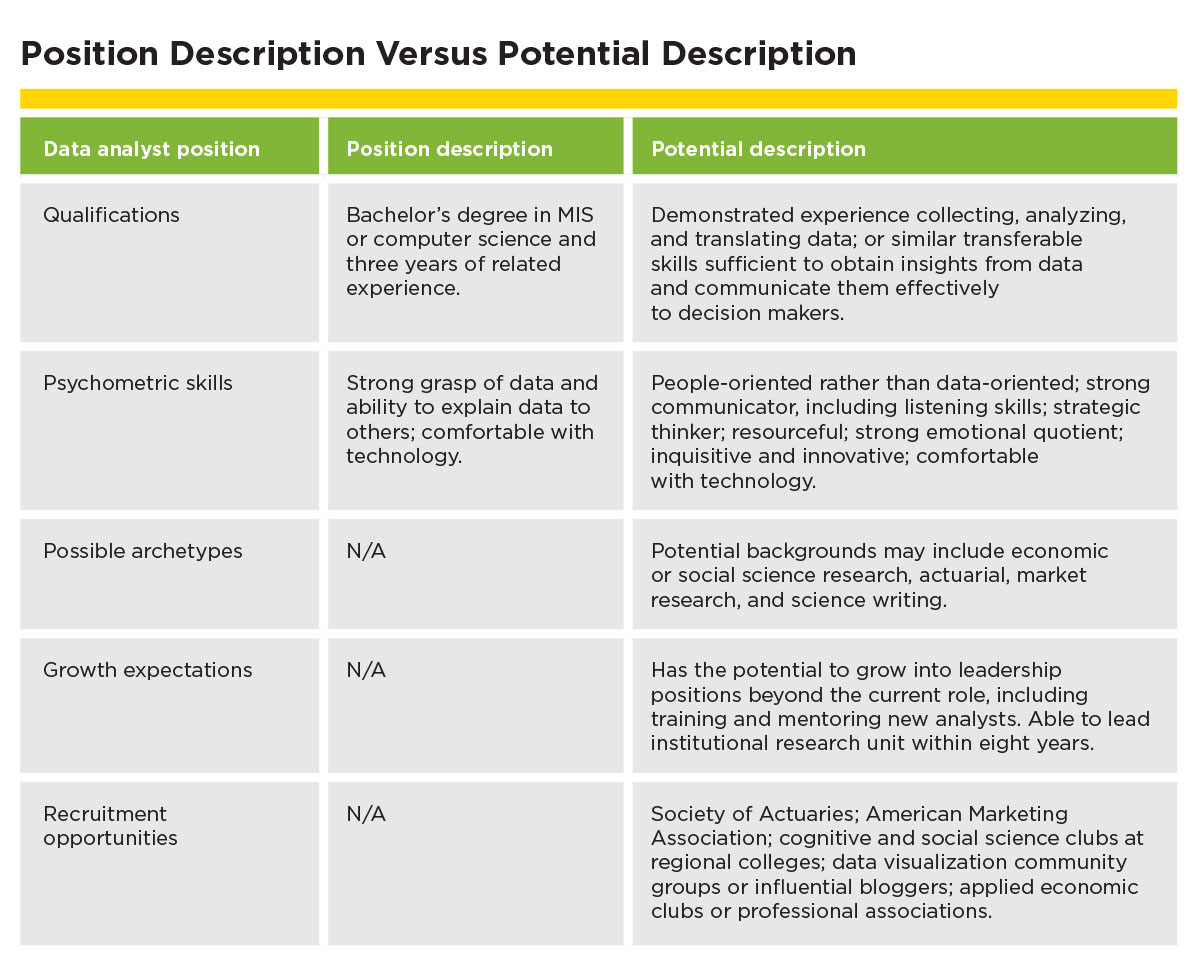

A recent hire for the University of Arizona’s business intelligence team illustrates the success that can come from consulting with colleagues on a potential job description. At the start of the process, the go-to thinking was to hire someone with an IT or information systems management background. As a result of an office discussion about the skills needed, team members realized they wanted a translator between technology and human use of data in decision making—someone who could communicate data with visualizations, who understood business processes, and who could support behavioral change (see sidebar, “Position Description Versus Potential Description”).

Through this reenvisioning process, the small pool of usual IT suspects expanded to include social and cognitive science researchers, which helped the university understand what talent really looked like for this position. Once you have a potential description, you can let it animate the position description. In the end, the university changed the IT position description based on its “potential” discussion and ended up hiring a cognitive scientist who has transformed the way data is used in the division; in fact, this individual was recently promoted to manager of the analytics team. By analyzing your needs upfront, you can reframe the entire process and may unearth potential candidates you had unconsciously excluded from your initial list.

Leave Room to Grow

Ultimately, it’s up to every hiring manager to determine what mix of skills and abilities are teachable, versus which traits are difficult or impossible to impart. That said, a prescriptive approach to the hiring process restricts rather than enables the success of any new hire. If you allow your organization to get trapped by a narrowly defined position description—and the limited thinking that accompanies it—you will likely be rewarded with a slim pool of potential candidates who may not live up to your hiring expectations or possess the skills and capacity to excel in the job and transform the role.

Regardless of the position vacancy, taking your hiring effectiveness to new heights will require first stepping back to see the forest before zooming forward to see the trees. The moment you start small, you’ve excluded candidates and limited your own field of vision. Ideally, a position description should be a sketch, not a finished painting. The final masterpiece is hiring someone who has the potential to fill in the open spaces, to grow beyond the current role, and to enrich the mission of your organization.

JEFFREY RATJE is associate vice president, finance, administration, and operations and treasurer, Arizona Experiment Station, division of agriculture, life, and veterinary sciences and cooperative extension (ALVSCE), University of Arizona, Tucson.

HEATHER ROBERTS-WRENN is former assistant director, organizational effectiveness, ALVSCE division business services, University of Arizona, Tucson.