Members of the NACUBO Sustainability Advisory Panel (SAP) knew anecdotally that many business officers devoted a chunk of their time to making campus operations more environmentally friendly. Yet it wasn’t until results of the panel’s recent survey came in that they had a good grasp on the variety and reach of sustainability activities taking place on campuses today.

“The compelling motivation for the survey was to determine where the panel should be focusing its efforts,” explains Fred Rogers, vice president and treasurer of Carleton College in Northfield, Minnesota, and chair of the Sustainability Advisory Panel. “We wanted to know what business officers are already doing in this area on their campuses and what they would find helpful for advancing those projects and programs.”

Similar Goals, Varied Approaches

Responses to the survey—and the many comments accompanying it—show that the components of campus sustainability programs are as diverse as institutions themselves. Some respondents, for example, have adopted comprehensive plans that incorporate LEED (Leadership in Energy and Environmental Design) principles into new construction and renovation projects, set aggressive goals for reducing energy usage, or expand use of alternative energy sources. Some emphasize the integration of sustainability into the curriculum or widespread community involvement. Others devote significant efforts to large-scale recycling or composting programs. And many institutions undertake projects in all these areas and more.

“People talked about many different sustainability initiatives on their campuses. There was a fair amount of breadth reported, particularly in the open-ended responses,” notes Sheri Tonn, vice president of finance and operations at Pacific Lutheran University in Tacoma, Washington, and a SAP member.

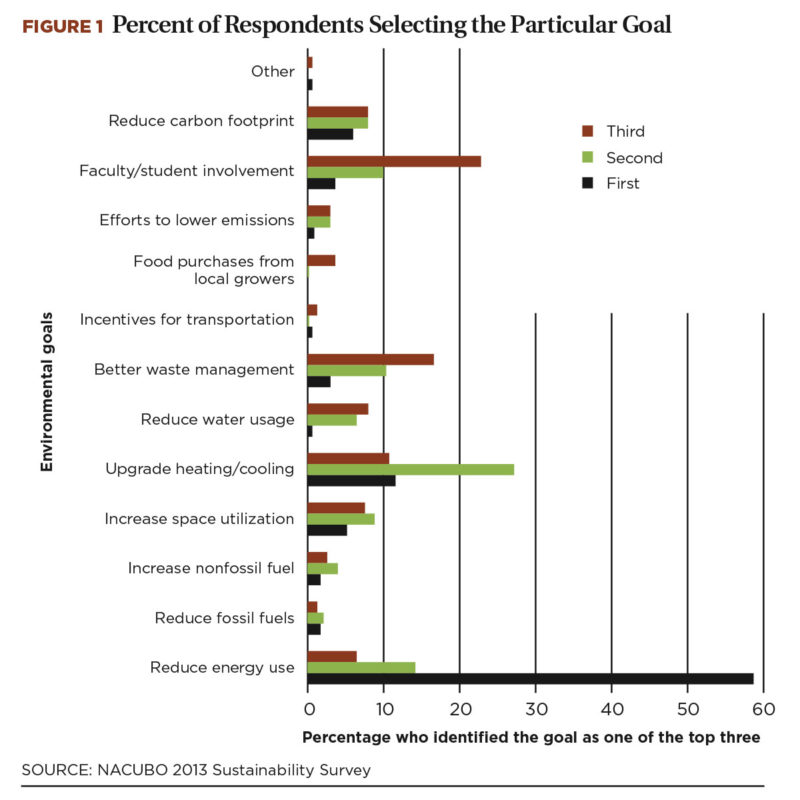

That said, an overwhelming majority of respondents gave similar answers to several questions. When asked to rank their top three goals (see Figure 1), for example, all constituent groups selected the same priority: reducing energy use. This goal proved especially critical to research institutions and those in rural areas. The second and third priorities were upgrading heating and cooling systems, and faculty/student involvement.

“Not surprisingly, most schools are focused on the basics: improving the efficiency of their heating and cooling plants, and lowering operating costs, while continuing to provide comfort and convenience for the campus,” says Rogers. “That’s the meat and potatoes of what we do as business officers. The two top goals show that we all realize we can do better and get smarter about operating and maintaining the whole campus.”

Lower the energy bill. His own institution recently installed new metering equipment and is upgrading its digital building control systems. Also, in several of its largest buildings, Carleton has switched to a lighting control system that automatically reduces light levels in unoccupied rooms and library stacks.

Energy management efforts for the Kentucky Community and Technical College System (KCTCS) date to 2004, when the group of 16 colleges and more than 70 locations first ventured into performance contracting as a means to achieve energy efficiency. As an inaugural participant in the U.S. Department of Energy’s Better Buildings Challenge, KCTCS has committed to achieving a 20 percent reduction in its energy consumption by 2020.

Even better, “We’re already well ahead of our estimated cumulative guaranteed annual savings targets from our energy-saving performance contracts, saving about $7 million a year,” reports Billie Hardin, sustainability project manager for KCTCS. She estimates that KCTCS will register systemwide savings totaling $28.1 million annually and reduce total energy consumption by 17 percent, along with a 26 percent reduction of water and sewer consumption.

“We’re looking at our energy management program as a means to manage and offset our carbon footprint,” Hardin adds. “Kentucky has relatively low utility rates compared to other states, but we know we’ll be hit with increases as fossil fuels go offline and coal power plants close. We want to be well situated when those things happen.”

Overall, slightly more than one in five respondents (22 percent) mentions reducing the institution’s carbon footprint as a main sustainability goal. Far fewer make it a priority to increase use of nonfossil fuels (9 percent), lower emissions (7 percent), and reduce use of fossil fuels (6 percent). Rogers suspects those goals would rapidly move higher up the list should state or federal legislators seriously consider enacting a carbon tax.

Focus on nonfossil fuels. Perhaps anticipating that scenario, Carleton has been operating a commercial-grade wind turbine for more than a year; a second one recently came online. “Between the two, we’re generating more than half of our electrical power from wind and selling some to the grid,” Rogers reports.

Although Carleton and Pacific Lutheran University (PLU) have similar-size enrollments, their disparate geographic locations dictate different approaches to the same goal—a reality behind many of the survey’s findings. As an example, says Tonn, “We don’t have enough wind for a turbine on our campus, but geothermal heat pumps are an excellent match for our temperate climate, where we may need heating one day and cooling the next day.”

PLU, which aims to reach carbon neutrality by 2020, has also ventured into solar power; about a year ago, the university retrofitted its facilities building with a rooftop array of panels. Grants from an education foundation and a local utility covered much of the costs. “The state of Washington has an incentive program that pays us 54 cents a kilowatt hour for every kilowatt hour we generate with solar,” Tonn notes. “We pay only about 5.5 cents, or about one tenth of the kilowatt hour charge, for the electricity we buy. The incentives aren’t a long-term program, but they sweetened the whole deal.”

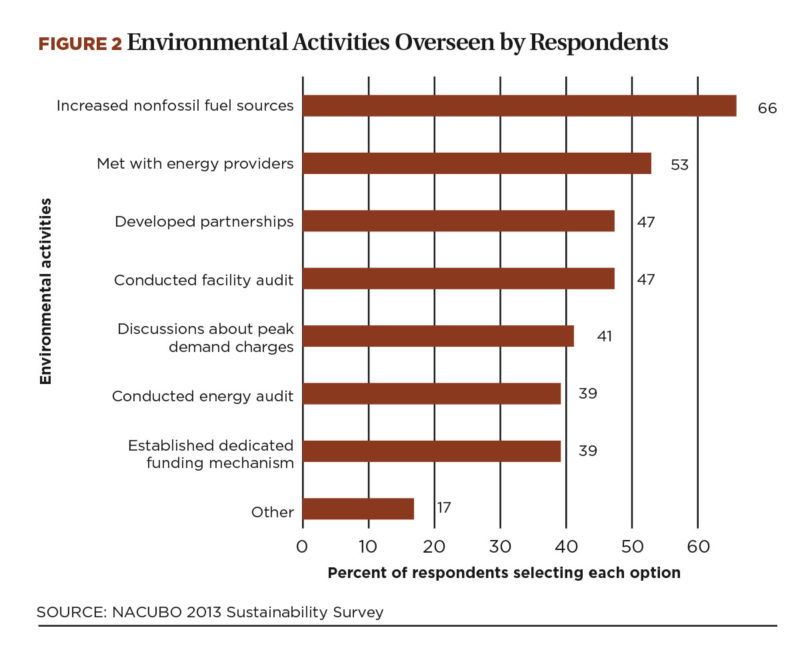

Given the potential financial incentives, it makes sense to Tonn that two out of three survey respondents (66 percent) say they have personally overseen their institution’s exploration of increasing use of nonfossil fuel sources. That activity topped the list of CBOs’ personal involvement with sustainability on campus (see Figure 2), followed by meeting with energy providers (53 percent of respondents had done so within the previous six months).

Developing partnerships and conducting a facility audit were both reported by 47 percent of CBOs, followed closely by holding discussions with utility companies about peak-demand charges (41 percent), with the goal of lowering overall costs. (Most utility costs are based on annual consumption as well as the peak demand of the campus; while lowering either component can reduce costs, lowering both achieves significant savings.)

Approximately two out of five respondents (39 percent) have overseen an energy audit, with the same percentage having established a “green projects” revolving fund or other dedicated funding mechanism to support the institution’s sustainability activities.

Supporting Sustainability Expenses

By far, funds for campus sustainability efforts come from the general operating budget: Nearly nine out of 10 respondents (88 percent) rely on the operating budget to fund activities, a finding that holds steady across all constituencies.

“That consistent reliance on the operating budget shows that everyone views sustainability and energy initiatives as being no different from the other things funded by the operating budget,” says Sheri Tonn. “In other words, sustainability is likely a multiyear commitment on the part of the university, one that will be addressed incrementally.”

- Beyond the operating budget. As a funding source, grants, rebates, or savings from current or previous sustainability efforts come in a distant second (reported by 46 percent of respondents). Overall, nearly two out of five (38 percent) rely on the use of bonds, debt financing, or commercial paper to fund their sustainability efforts, although for research universities that figure is approximately two out of three (65 percent). Research institutions are also far more likely than overall respondents to finance initiatives through student or user fees (35 percent versus 12 percent overall). About one fourth of all respondents (23 percent) have reduced deferred maintenance facilities by funding sustainability projects, and only 6 percent of all respondents report using endowment funds.

One in 10 tap “other” sources of revenue. Based on the write-in responses, these sources may be as traditional as private contributions and targeted gifts from donors, and as creative as selling for scrap some assets no longer used on campus.

- Resourceful combination and coordination. To finance a major project begun in 2011, the Boston Architectural College (BAC) drew on multiple sources. The two-pronged sustainability initiative includes demonstration projects to drill eight geothermal wells and construct a “green alley” between several buildings to direct roof water runoff into the ground rather than into the stormwater system. “The costs of implementation were partially covered by direct grants from the U.S. Department of Energy, the Massachusetts Department of Environmental Protection, and the City of Boston, all of which totaled approximately $2 million,” says Kathleen Rood, BAC’s vice president for finance and administration. In addition to cost sharing, a portion of which came from the college’s online sustainable design programs, another $700,000 in operating funds provided the balance of the funding.

The geothermal wells, drilled to a depth of 1,500 feet, will eventually heat and cool BAC buildings, eliminating the use of natural gas on campus. As for the green alley, it is simply mimicking nature, notes Art Byers, associate vice president of facilities. “By removing impermeable paving and replacing it with permeable materials, we are allowing rain water and snow melt to penetrate to the groundwater layer,” says Byers. “Initial data indicate a 100 percent reduction in impact on the stormwater system, for storms up to 2.5 inches.” The college hopes to reduce sewage overflows into the local Charles River, as well as water treatment costs, and recharge the water table that maintains the wood pilings that support Boston’s Back Bay area buildings.

Results Recap

Like Boston Architectural College, KCTCS depends on partnering with other entities to advance its sustainability goals. Many institutions have followed the same path, as evidenced by the 61 percent of CBOs who report their institution has, over the past five years, developed new partnerships or collaborative efforts related to sustainability.

“To achieve true sustainability, you have to build a community—and to build a community, you need to collaborate and build partnerships,” emphasizes Billie Hardin. KCTCS, for example, participated in the Mentor Connect Partnership Program sponsored by the American Association of Community Colleges’ Sustainability Education and Economic Development (SEED) Center. “Through the program, we sponsored two trainings: one, in collaboration with Automotive Research and Design LLC, certified automotive faculty in hybrid car technology; and another, in collaboration with two North Carolina colleges (Wake Forest and Davidson), focused on integrating sustainability into the curriculum,” says Hardin.

The program enhanced sustainability-related program development and resulted in an associate degree and diploma in energy management, five new certificate programs (including green building technology and sustainable energy), and the expansion of the system’s agricultural program to include a sustainability track.

Other survey respondents also report a wide range of partnerships and collaborations, with cities, government agencies, consortia, vendors, utilities, corporations, and community groups. Just as diverse are the reasons for collaboration, such as decreasing the campus waste stream, increasing recycling efforts and sales of recycled products, providing alternative transportation, supporting local farmers, and—mentioned most often—reducing energy consumption.

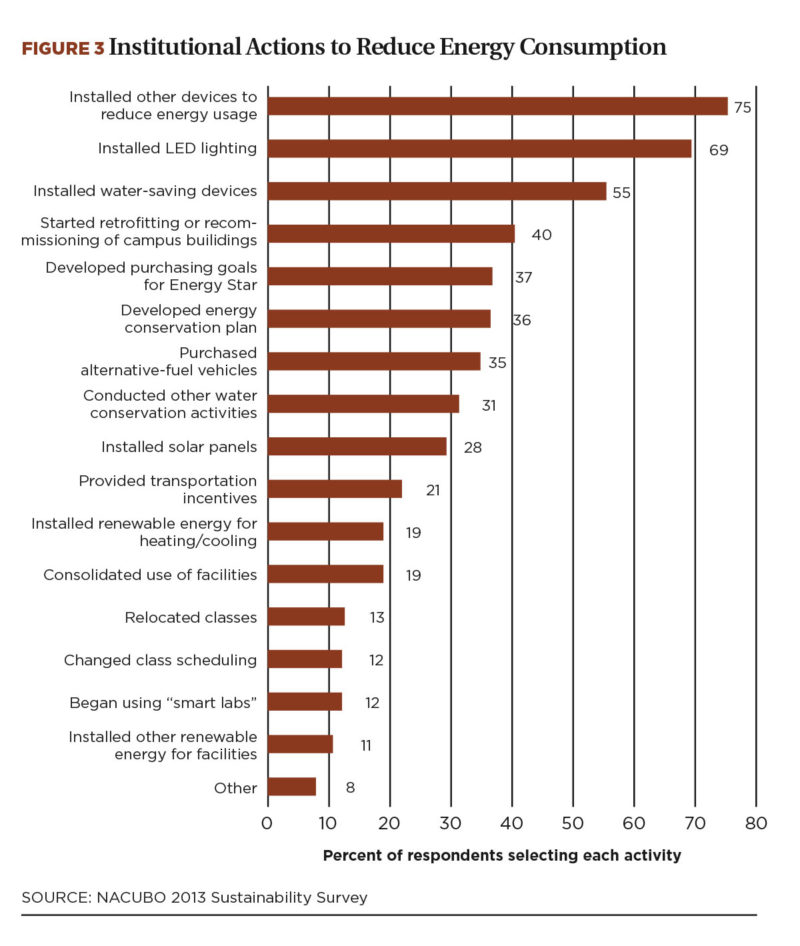

Whether solo or in partnership, within the past three years, three of four respondents (75 percent) report having installed various devices to reduce energy consumption on their campuses (see Figure 3). Running a close second is the installation of LED (light-emitting diode) lighting (reported by 69 percent), followed by the installation of water-saving devices (55 percent). Compared to the overall sample, respondents from rural, large, and research institutions, as well as those from community colleges, are far more likely to have engaged in retrofitting or recommissioning campus buildings, with 68 percent of research institutions and 57 percent of community colleges, respectively, favoring such activities.

Here are additional highlights:

- Time commitment. The majority of CBOs responding to the survey (54 percent) believe they spend an adequate amount of time on sustainability, although 46 percent would prefer to increase that time. In general, CBOs devote less time to student engagement related to sustainability and more of their time to addressing energy efficiency and space management issues.

- Incentives. About three out of five (60 percent) say their institution has taken advantage of state or local tax breaks, utility credits, or other incentives related to sustainability or environmental protection. Of those, 76 percent believe the incentives had a positive effect.

- Increased knowledge. When asked to select three topics on which they’d like more information, respondents mirrored their institutions’ top goals, to some extent. The No. 1 request (50 percent) was to learn more about reducing campus energy use; followed by 38 percent wanting information about funding options for energy, infrastructure, and sustainability improvements; and 31 percent desiring more information on faculty/student involvement.

Other options rose to the top of the want-to-know list, including space utilization; respondents wanted to know about such activities as consolidating, compacting, or demolishing classrooms, labs, or other facilities. (For a related article on the sustainability aspects of space utilization, see “Spatial Concepts”.)

Learn From Other Leaders

While some of the survey findings may not seem cutting edge, Rogers hopes CBOs will share their successes with colleagues at other institutions where sustainability initiatives may be just gaining traction. “Because the sustainability field is moving so rapidly, people may feel that an interesting innovation from 5 or 10 years ago has been adopted everywhere—but that’s not necessarily the case,” says Rogers.

“Take water conservation and better waste management, for example,” he continues. “Those aren’t as sexy as, say, putting in charging stations for electric cars, but they’re fundamental to improving how a campus operates. There’s still a lot of work to be done in the main areas.”

SANDRA R. SABO, Mendota Heights, Minnesota, covers higher education business issues for Business Officer.