Two principal challenges facing four-year private, nonprofit colleges and universities today appear essentially antithetical, placing institutions in a precarious situation. On the one hand, institutions face a charge from students and their families, as well as policymakers, to keep higher education affordable. On the other hand, these institutions find themselves in financially arduous times, with some facing concerns about tepid market conditions, waning enrollment, and the difficulties of fundraising, and witnessing a small number of peer institutions making decisions to close or merge with other institutions. The practice of tuition discounting is at the crossroads of these issues.

Findings from the 2017 NACUBO Tuition Discounting Study (TDS) shine a spotlight on the efforts of college and university business officers to meet these seemingly competing objectives. As the study highlights, campus leaders face myriad challenges related to these fundamental goals as tuition discount rates, on average, continue to rise for four-year independent colleges and universities.

Rising Rates

With tuition discounting, colleges and universities provide institutional grant aid to students to offset, or “discount,” the published tuition and fee price. Various discounting strategies are used to attract or retain students who are unable or unwilling to pay the full tuition and fee “sticker price.” Although tuition discounting is used at both public and private colleges and universities, the TDS has historically focused on four-year private, nonprofit institutions, because they typically award larger amounts of institutional aid.

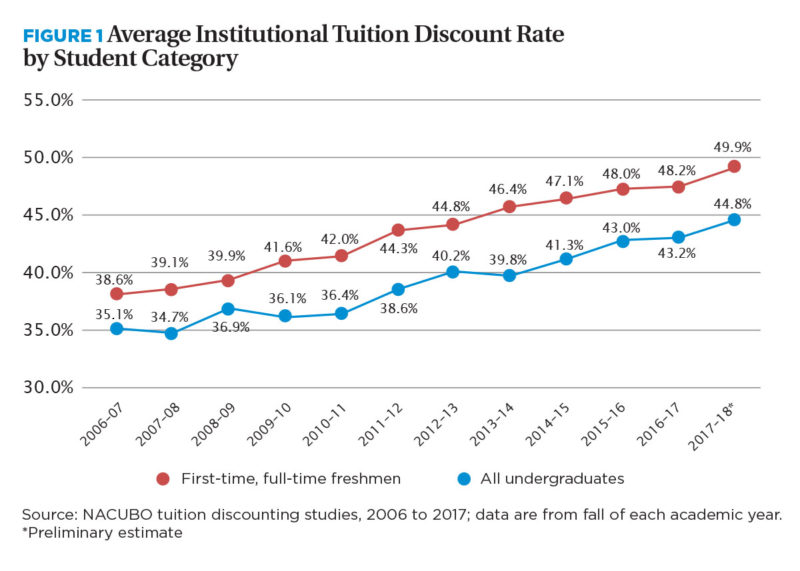

Institutional tuition discount rates—the proportion of tuition and fee revenue used to support undergraduate institutional grant expenditures—at independent institutions have steadily risen over the last decade. As Figure 1 shows, from 2006–07 to 2016–17, the average institutional tuition discount rate for first-time, full-time freshmen increased from 38.6 percent to a record high of 48.2 percent, and is estimated to reach 49.9 percent in 2017–18. Among all undergraduates, the average institutional discount rate is estimated to be 44.8 percent in 2017–18. This means that on average for every dollar they collected from all undergraduates in tuition and fees, private nonprofit colleges awarded $0.45 to institutional grant aid recipients.

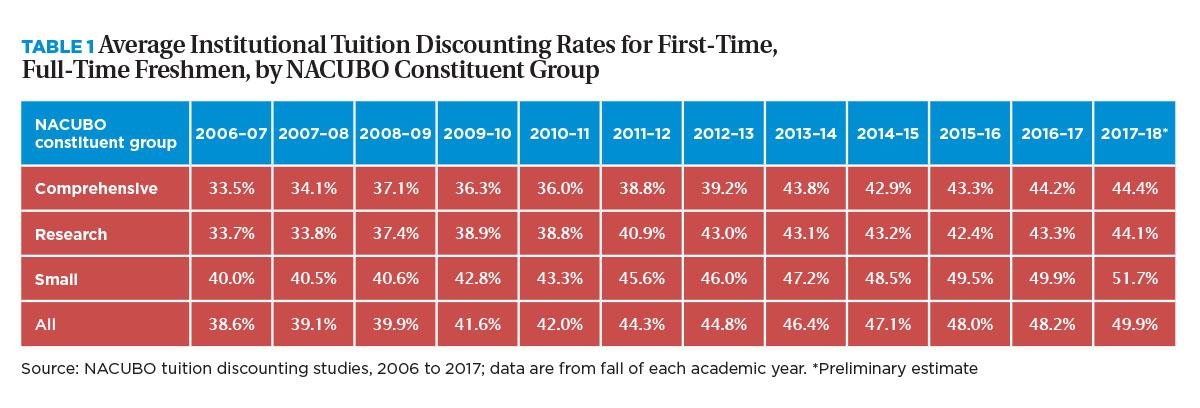

There is variation in institutional tuition discount rates by institution type. Small institutions’ freshmen tuition discount rates reached a record average of 49.9 percent in 2016–17 and are estimated to climb to nearly 52 percent in 2017–18 (see Table 1). In contrast, institutional freshmen discount rates at research universities and comprehensive/doctoral institutions, on average, are estimated to be 44.1 percent and 44.4 percent in 2017–18, respectively.

Supporting Student Access

These differences highlight the importance of understanding institutional contexts when looking to the tough balancing act campus leaders must accomplish when focusing on priorities for their students and their campuses alike.

Tuition discount rates at independent colleges and universities continue to rise because institutions are providing grant aid to more students, and the grant awards students receive cover a larger share of the published tuition and fee price.

The TDS includes two ways to measure the impact of tuition discounting on student recipients. First, the study considers the average percentage of undergraduates who are awarded institutional grants and scholarships; second, the TDS calculates the “student discount rate,” or the average grant amount as a share of the average tuition and fees sticker price.

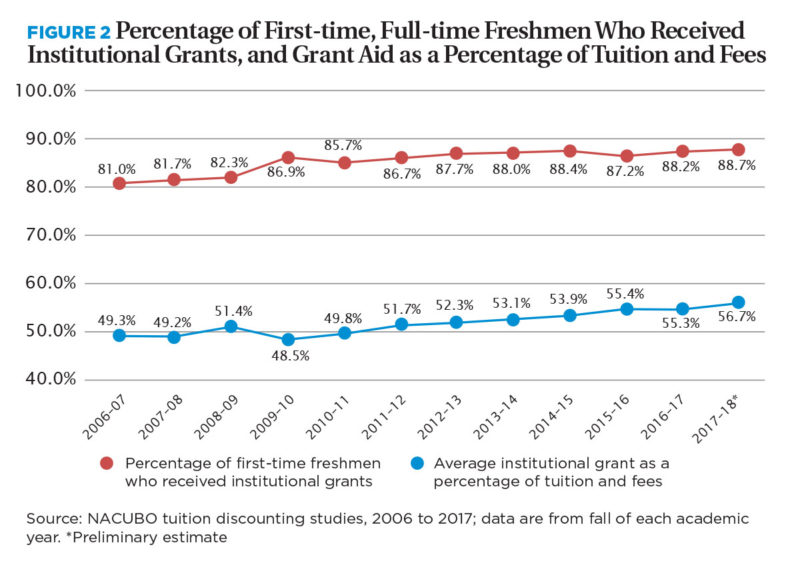

Over the past decade, a higher share of first-time, full-time freshmen attending independent colleges and universities have received institutional grant aid, and this aid has covered a larger share of their tuition and fees (see Figure 2). In 2017–18, nearly 89 percent of first-time, full-time freshmen were awarded institutional aid, compared with 81 percent in 2006–07. And on average, the share of the average published tuition and fee price covered by the average award rose from about 49 percent to nearly 57 percent.

Lebanon Valley College, Annville, Pa., is one institution that has seen a dramatic increase in its institutional aid awards. The college awarded more than $39 million in institutional aid to undergraduates in 2017–18, according to Shawn P. Curtin, vice president of finance and administration. “Increases in institutional aid have been some of the largest investments Lebanon Valley College has made over the past several years,” he points out. “We have worked hard to ensure we remain affordable and that students can progress and graduate on time with a high-quality education and the ability to secure a good paying job, or be well prepared to enter graduate or professional school.”

Carleton College, Northfield, Minn., provided approximately $41.8 million in institutional grants and scholarships to undergraduates in 2017–18, and has also seen recent increases in institutional financial aid expenditures. “Our grant aid has increased by an average of 5.7 percent annually over the past five years,” says Fred Rogers, vice president and treasurer.

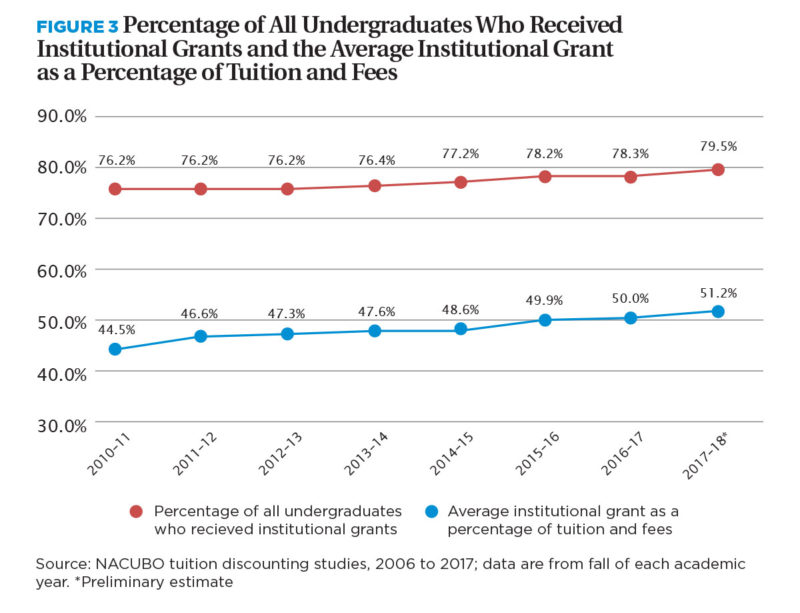

In addition to measuring discount rates for first-time, full-time freshmen, the TDS considers measures for all undergraduates, which include upperclassmen as well as part-time, transfer, and specially enrolled undergraduates. These data indicate that trends for all undergraduates are similar to those for first-time, full-time freshmen. As Figure 3 shows, in 2017–18, the TDS estimates that nearly 80 percent of all undergraduates were awarded institutional aid and that, on average, this aid covered more than 51 percent of the listed tuition and fee price.

With more students being awarded institutional aid that covers more than half of the listed tuition and fee price, the priority that institutions place on access to higher education, as well as the role of tuition discounting in enrollment management practices, are evident.

Since Lebanon Valley College’s introduction of a new institutional aid program in 2016, Curtin explains, “We are making progress with goals outlined in our strategic plan,” which include, “goals for increasing our recruitment geography, the percentage of international students, and an increase in racial/ethnic diversity.”

In addition, Rogers explains the important role of institutional practices when considering access and affordability at Carleton College. “We increased our budget for campus visits as well as increased targeted scholarships for income-specific populations, which we believe have helped Carleton maintain enrollment and socioeconomic diversity.”

Merit- Versus Need-based Aid

Although many acknowledge that financial aid plays a role in providing access to a postsecondary education, some critics express concerns that the goals of student access and retention are being thwarted by institutions’ focus on prestige, as seen by the portions of aid awarded based on students’ academic merit and other “non-need” criteria, rather than exclusively demonstrated financial need.

However, Kathleen Dawley, managing director of client success for EAB, Richmond, Va., and a former member of the board of trustees at Regis College, Weston, Mass., says, “There is a distribution design in [merit aid] policies that has to do with providing more funding as the ability to pay decreases … so low-income students in general are being well-funded, particularly the lowest income groups.”

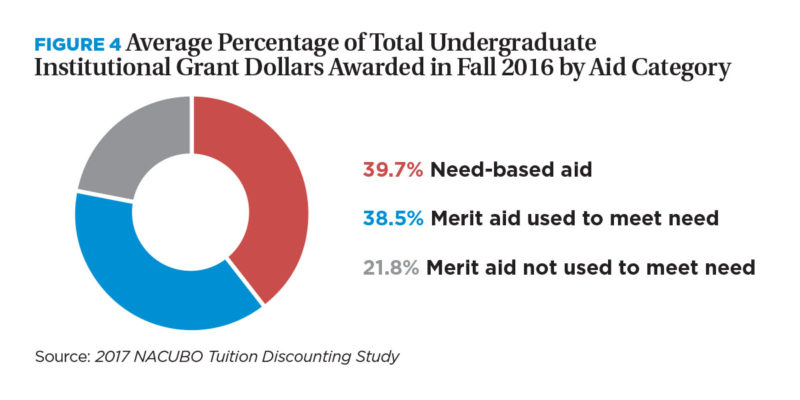

Data from the most recent TDS illustrate Dawley’s point. The TDS collects data on the proportion of institutional scholarships and grants awarded based on need- and merit-based criteria. In 2016–17, about 39.7 percent of institutional aid was awarded based exclusively on students’ demonstrated financial need (see Figure 4). Approximately 38.5 percent was awarded on the basis of merit or other “non-need” criteria, but was received by students who had some level of financial need. This means that, on average, 78.2 percent of total institutional grant aid awarded at private nonprofit colleges and universities in 2016–17 was used to meet students’ financial need (which includes need-based aid combined with merit aid used to meet need).

Balancing use of merit- and need-based criteria to best serve students is highlighted by various institutional policies, which likely vary by campus and can evolve over time. Curtin explains that in Lebanon Valley College’s new institutional aid program, one goal is to “ensure we remain affordable for the students we recruit.” He adds that the program, “continues to be merit-based, but takes into account many more factors when evaluating student high school achievements,” and the program “continues to offer need-based aid for students who demonstrate financial need.”

EAB’s Dawley also notes that some campuses have been experimenting with how to use merit aid to address another issue that is important to both students and campus administrators: retention. “There are a few institutions that are beginning to look at awarding merit aid to continuing students, particularly those who did not receive merit aid when coming into the institution but who are doing well.” She explains, “It’s rewarding good academic progress and meeting some financial need.”

Consideration of Tuition Revenue

Although increasing tuition discount rates can benefit students and help colleges and universities in realizing their access and affordability goals, discounting tuition and fees for students may have implications for institutions’ net tuition revenue. According to data from the National Center for Education Statistics, four-year private, nonprofit colleges and universities rely on student tuition and fees for about a third of their total revenues. Thus, changes in per-student net tuition and fee revenue—calculated as per-student gross tuition and fee dollars minus institutional grant aid—is an important measure for understanding the effects of discounting on college and university finances.

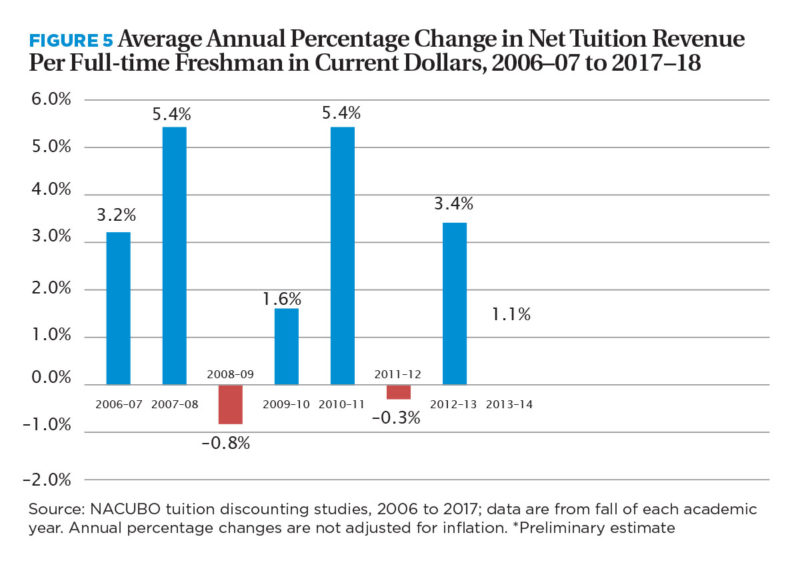

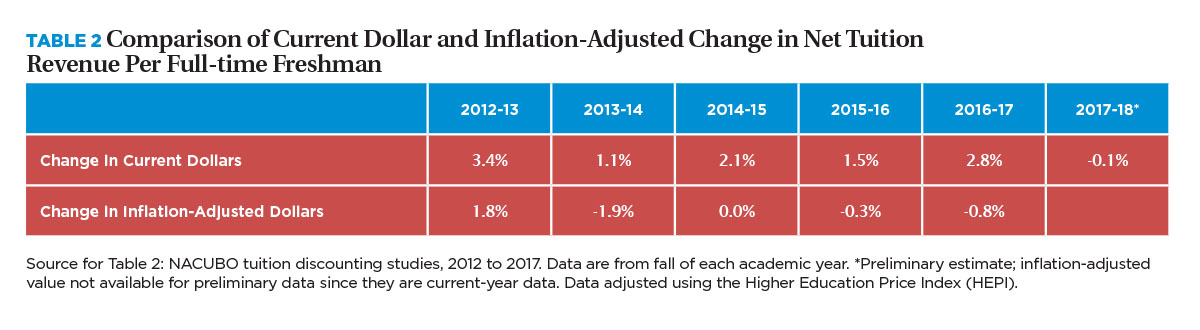

From 2006–07 to 2012–13, annual changes in net tuition revenue per first-time, full-time freshmen were quite volatile—ranging from 5.4 percent in 2007–08 to –0.3 percent in 2011–12 (see Figure 5). However, Table 2 illustrates that, in more recent years, the annual changes in net tuition revenue per freshman have been relatively low, and, when adjusted for inflation, have been essentially flat or negative.

Considering these trends, Dawley provides some context. “Before the Great Recession in 2008, there was a run-up of institutional cost increase. It wasn’t unusual to see 6, 8, even, in some cases, 10 percent increases annually. Since the recession, annual tuition increases have been very modest, hovering around 3 percent, or less in some cases. This means that the revenue coming from tuition is flatter or declining for two reasons: control of the discount and these relatively modest increases in tuition and fee prices.”

These trends beg the question: What strategies will colleges and universities use going forward, as they balance the expectations and needs of students with the realities of waning net tuition revenue growth?

Putting It All Together

The financial challenges many institutions are facing may lead to shifts in their spending strategies, Dawley explains. “Until the recession, there was a run-up over the last couple of decades to build more, provide more—to enhance athletic facilities and fitness centers, to build more residence halls and new student centers. And it was all warranted by the competitive environment. Now we see less investment of that nature going on or anticipated in the foreseeable future.” In short, Dawley explains, this is a campus shift from a focus on the “nice to haves” to recognition of the “must haves.”

A number of campuses have tried new strategies to increase net revenue while controlling institutional grant expenses. At Carleton College, “We are facing increasing pressure and are not sure if we can sustain the growth in our financial aid budget indefinitely,” Rogers says. To address this concern, he explains, “We have a major goal for raising financial aid endowments.” Further, his institution has gained footing with new academic programs to support revenue. As a result, “Carlton’s net tuition revenue has grown an average of 2.9 percent annually over the past five years. This includes a significant increase in Off-Campus Studies revenue from newly acquired programs, which experienced a 7.3 percent increase over the same period.”

Describing his institution’s process for viewing sustainability in a holistic manner—considering both undergraduate and graduate tuition revenue—Curtin says, “Lebanon Valley College has increased significantly the amount of institutional grant aid provided to students over the past several years. Through our modeling, we knew that our net tuition revenue would remain flat, if not decline slightly in the short term. We expect this trend to stabilize in the next couple years, as students progress into graduate and professional years of several new accelerated masters and professional doctorate programs added as part of our strategic plan.”

Throughout all these initiatives, students remain the priority on campuses. Curtin acknowledges, “Lebanon Valley College has taken proactive and aggressive steps to broaden the revenue base and manage costs, while continuing to fulfill our mission and provide meaningful outcomes for our students.”

LINDSAY K. WAYT is assistant director, research and policy analysis, NACUBO.