A decade ago, the University of New England (UNE), with campuses in Biddeford and Portland, Maine, had an unclear institutional identity and no cash reserves. Its three colleges enrolled fewer than 4,000 students, and its CIC Composite Financial Index was 1.4.

But today, the university is recognized for the quality education it offers and its strong return on investment. UNE’s six colleges enroll more than 12,000 students, and its CIC Composite Financial Index is 5.9. In this article, we share how we worked together to help the university achieve transformational change.

A New Vision

In September 2006, members of UNE’s campuses in Biddeford and Portland gathered to swear in the university’s fifth president, Danielle N. Ripich. At the time, such gatherings were rare. After the merger of Portland’s Westbrook College with the University of New England in 1996 to create the new University of New England, the Portland and Biddeford campuses continued to operate more or less independently of one another. The faculties of the two campuses (a third, in Morocco, to be added later) worked in silos, following separate handbooks, and rarely finding opportunity to interact with their colleagues just 20 miles away. There was no universitywide graduation ceremony and no cohesive UNE mission or shared sense of purpose.

The new president strongly encouraged the campus community to embark on a journey that would take UNE far from its moorings as a small, tuition-driven institution, unable to break through the 4,000-student mark, and forced to tap into its line of credit two summers in a row just to make payroll.

The president was intent on building a thriving, modern university, complete with competitive advantages that created real value for students. She envisioned making UNE a hub of innovation, not just in Maine, or in the Northeast, or even in the U.S., but globally.

We knew that this would not be easy to accomplish. It would require tremendous change and thoughtful growth—not just institutionally, but on an individual level for employees courageous enough to take stock of all the negative trends facing small, private, tuition-driven universities at the time, and to resolve to defy and overcome them.

Moody’s and other industry experts were predicting a prolonged period of consolidation and retraction in higher education, especially for private institutions in the saturated Northeast, and particularly for those located in aging states such as Maine. The doomsayers weren’t wrong. The trends they identified did become the new realities for many schools, thanks in part to the additional stresses created by the Great Recession. But for UNE, the next 10 years were a period when the institution:

- Experienced exponential enrollment growth.

- Launched three new colleges, one of them fully online.

- Opened an international campus in Tangier, Morocco.

- Undertook the construction of more than a dozen new buildings.

- Attained an unprecedented degree of financial health.

In order to make these achievements, staff had to adapt to new ways of doing business, and learn to live with the sort of ambiguity more characteristic of a Silicon Valley startup than a higher education institution. Making this change was harder for those who had chosen to spend their lives in a system where layers of committee work and bureaucratic red tape usually lie between the entrenched work habits and new methodologies. But, staff was able to slowly embrace change when they saw senior administrators lead by example.

The CBO, too, played an integral role in helping the new president create a growth-minded culture, by stepping outside the industry to develop data points beyond those traditional metrics used in higher education, and looking well below the surface of the university’s operations to uncover valuable new information on which to base decisions. For example, UNE:

- Engaged a research firm to undertake a market study, researching workforce needs and patterns. This firm had never worked in higher education before.

- Commissioned an economic impact study that provided data to:

- Confirm the economic contribution UNE was making to the state of Maine, which subsequently helped with fundraising from foundations.

- Demonstrate a $250 million contribution to the state in 2007, which would make a $1 billion economic impact by 2016.

Realizing the challenges of connecting the dots for trustees, faculty, and other university stakeholders amid the fast-moving, dynamic environment that the president was cultivating, the CBO learned to present data in new ways, such as preparing infographics that made complex metrics more readily accessible. If the president supplied the vision or the “why,” the CBO helped to figure out the “how.” Together, our centralized approach to management kept UNE nimble and quick to adapt as it built or renovated more than a million square feet of space on three campuses, and created new programs that solidified its new mission as a university committed to “innovation for a healthier planet.”

As the president recognized from the start, the market potential for this Maine-based school had to be targeted. The greatest areas of potential growth were in the health professions, graduate programs, global education, online programs, and competency-based education. We worked together to build a financial program that translated these potential areas into a reality, and, subsequently, made UNE a leader in each area.

Building a Better Future

In addition to inheriting a fragmented campus community and a tenuous balance sheet, the president took the helm of an institution that had made very few capital investments in the previous decades. The university also lagged significantly behind industry standards in terms of its information technology. After undergoing 15 audit findings in recent years, UNE was exceeding its financial aid budget each year. What’s more, its tuition was rising at an unsustainable rate, and the lack of student housing suggested that it ran the risk of becoming a commuter college.

Getting the administrative systems under control—quickly—was an early goal of the new president. Doing so would help establish credibility with UNE’s board of trustees. Toward this end, the CBO played a leading role in quickly overhauling and creating systems that were effective, so that the president and board could focus on implementing the strategic vision. One of the administrative changes the president made was to dismantle the university’s enrollment management system, while disentangling the offices of admissions, financial aid, and registration. This new structure allowed admissions to report directly to the president, financial aid to the CBO, and registration to the provost. As a result, admissions’ priority of meeting its enrollment targets no longer superseded financial aid’s budget limitations. Financial aid remained in line with its budget and had no audit findings, and admissions focused on other ways to attract qualified students.

The president also saw an opportunity to make UNE a comprehensive health sciences university. She recognized that the region and its population would only have more health-care needs in the years to come. And yet, the region had no college of pharmacy or dental medicine, and offered limited educational opportunities for men and women interested in fields such as physician assistant, physical therapy, occupational therapy, nurse anesthetist, and nursing. UNE already had a College of Osteopathic Medicine on the Biddeford campus and a handful of successful health professions programs on the Portland campus. Now, the opportunity existed—at once—to fill a market niche, unify the two campuses behind a central health education mission, and build the university’s brand as a leader in the health sciences.

The task of translating this vision into reality was complicated by UNE’s maxed-out credit line, limited borrowing capacity, and credit rating that ranked below junk-bond status. The only way forward was to create programs that generated sustainable revenue streams. As president and CBO, we adopted a mantra of “no market, no margin, no mission,” recognizing that without financial stability it wouldn’t matter what UNE’s mission was.

Creating an Integrated Budgeting Model

It was clear to us that establishing a strong financial base was essential to building a modern university. With this in mind, we developed a new budgeting model that incorporated aspects of three different budget models—incremental, revenue center management, and strategic initiative—all with strong central administration oversight.

- Incremental. The UNE model is incremental in the sense that the budget is rolled over year-to-year to cover certain basic expenses, such as the costs of salary and benefit increases.

- Revenue center management. It follows a revenue center management model in the sense that UNE’s six colleges receive a portion of the increase in enrollment in their respective programs or lose funding when their enrollment declines.

- Strategic initiative funding model. But it is primarily a strategic initiative funding model that has allowed UNE to grow rapidly and remain flexible as the institution has invested in itself. The strategic initiative approach was the driver for the transformational investments that moved the university from a non-ratable institution to one with an implied rating range of A3 over the course of a tough decade in higher education.

The University of New England’s highly integrated and centralized approach has incentivized strategic growth and allowed the institution to capitalize on unforeseen opportunities. The careful market analyses and the shock and sensitivity analyses that the CBO developed assured the president and the board that each new initiative would not only cover its own expenses, but contribute to UNE’s central costs as well.

Pinpointing Growth Areas

At her very first meeting with the board, the president requested approval to build a college of pharmacy. She laid out a plan that explained how the new college would assist UNE in growing out of its tight financial situation.

Next, the president worked with the trustees and senior leadership to lay out a more comprehensive statement of where she intended to take UNE. Together, they drafted Vision 2017, a 10-year strategic plan that aimed to transform UNE into a thriving, modern health sciences university.

Then, as attention shifted from articulating UNE’s vision into making it the university’s deliberate new reality, the president and CBO worked together to create metrics and teach faculty and administrators to understand and value them. Together, we continuously reinforced the message that institutional will, focused goals, and fiscal discipline would enable UNE’s transformation.

Riveted on Revenue

In 2006, there was no college of pharmacy or dental medicine in northern New England, making it the largest geographic area in the U.S. without these colleges. Most thought that these expensive institutions were not sustainable, but UNE was committed to taking them on and making them successful.

The UNE College of Dental Medicine was initially approved by the Commission on Dental Accreditation to enroll 42 students per year. Before the university had even finished constructing its state-of-the-art Oral Health Center on UNE’s Portland campus, it realized that the flood of applications for its inaugural class suggested the need for a larger school. Ultimately, the fledgling college petitioned the commission to expand to 64 students per class. Upon notification that the request had been granted, one of the accreditors commented, “Congratulations, before opening your doors you’ve grown 40 percent. You’re the fastest growing dental college in the country.”

Likewise, when UNE launched the nation’s first fully online Master of Social Work, it anticipated 350 enrollees in the first year. After five months, the university had accepted 700 students and had a waiting list of 650 more. This program’s partnership with an evolving online company taught UNE how to succeed in this market. Later, when UNE was ready to run the online operations on its own, it launched the fully online College of Graduate and Professional Studies to house its existing online programs from its various colleges and create new programs within UNE’s areas of expertise. By the end of the 2016–17 academic year, the university’s online College of Graduate and Professional Studies will be its largest college, thanks in part to its 94.7 percent retention rate.

The success of these initiatives allowed UNE to build cash reserves to pay for those much-needed capital improvements that had been neglected prior to the president’s arrival.

The Investment Model

The creation of the UNE College of Pharmacy was followed by the development of plans for the UNE College of Dental Medicine. At the same time, UNE continued to launch cutting-edge online programs, began developing its first competency-based degree program—with help from an EDUCAUSE grant funded by the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation—and began rapidly expanding its global offerings, including plans to build a revolutionary science-based study-abroad campus in Tangier, Morocco.

The president and CBO ultimately developed a startup model for each of these new initiatives that involved wise internal investment and forgiveness of central cost for each innovation’s first six years. This period was determined to be enough time to iron out the wrinkles in new programs and make them successful. It also allowed time and room to fail—a little bit—while also limiting the time available to tweak the new programs when necessary.

The journey from startup to success was sometimes rough, but the nimble centralized management approach helped ensure that each new initiative returned revenue to the university before the six years were up. To stay nimble, UNE managed these new ventures via a steering committee that included the president, provost, chief business officer, and members of the senior administration. The group met monthly, reviewed projects, and made adjustments as needed. Every person in the room had the opportunity to offer their often-competing opinions before important decisions were reached. Still, the external environment—the Great Recession and sluggish recovery that followed it—challenged every initiative.

Economic Headwinds

The university’s resolve was tested early in the new president’s tenure. Less than two years after Ripich took the UNE helm, the subprime mortgage crisis set global economies reeling. As economic experts counseled “austerity,” “belt-tightening,” and other measures aimed at riding out the storm, the president could have put her plans on hold and hunkered down for the long, slow recovery that seemed sure to follow—that was what nearly every other institution was doing. Or, the president could steer UNE into the headwinds.

At the time, the university had just begun exploring an expansion plan to build a 300-bed residence hall in Biddeford that involved opening a new section of campus and navigating a slew of logistical hurdles, such as constructing a pedestrian tunnel under a busy road to allow students to transition from their bedrooms to their classrooms.

What’s more, the plan involved borrowing nearly $30 million at a time when lending had all but dried up. The president chose to invest in UNE, believing that the faculty and staff had the professional expertise necessary to provide a better return on investment than the volatile markets would deliver. The university would build the dorm, and it would fill it with new students.

Making a Comeback

The CBO worked with a credit partner to raise the money through a bond issue, and because of tough negotiating by UNE Vice President of Operations Bill Bola, the university was able to secure an advantageous deal. Because so many contractors were scrambling for work at that time, their bids came in well below pre-recession estimates. After managing to complete the project under budget, the university put the $3.5 million surplus toward the construction of a blue synthetic turf field near the new residence hall. In the years to follow, the field became a signature part of the Biddeford campus and its presence, along with that of the residence hall, helped UNE make the case to the Harold Alfond Foundation for a $10 million grant—the largest in the university’s history—to help build a state-of-the-art athletics facility between the new Sokokis Hall and the Big Blue Turf field.

That same year, UNE created a salary raise pool of 6.5 percent that moved faculty compensation ahead, when other institutions were freezing increases. Out of these bold decisions—to build when others were putting capital plans on hold and invest in human capital when others were not—flowed a cascade of new opportunities, accelerating UNE’s growth into the flourishing, modern university it has become.

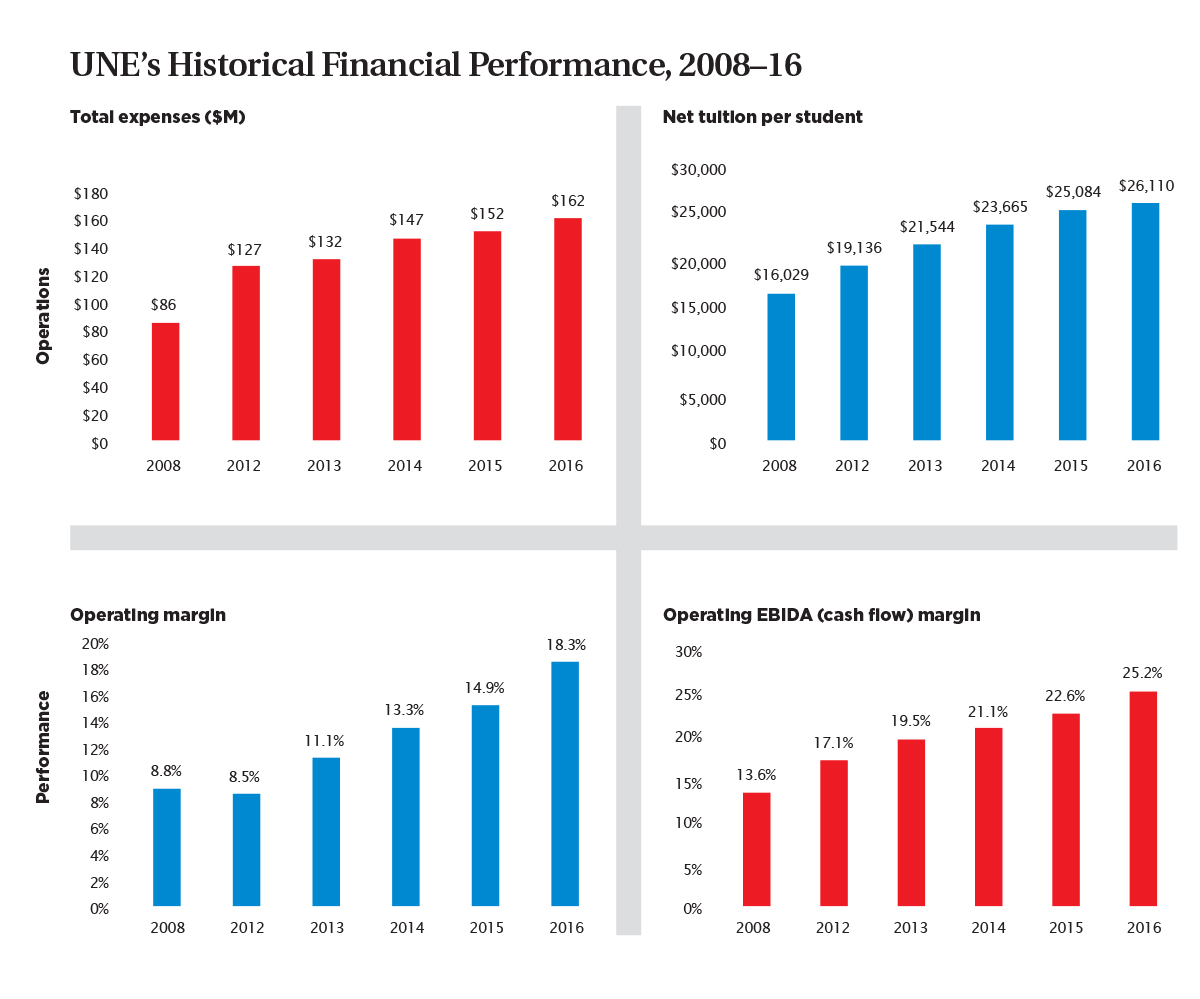

As it has expanded in so many ways, while simultaneously improving its academic profile, UNE has dramatically improved its financial and credit positions through the execution of key strategic priorities and fiscal discipline. The university’s current credit strengths include:

- A solid market position in high-growth educational programs.

- Diversified sources of tuition revenues.

- Historically strong and stable cash flow generation.

- A solid wealth position as reflected by significant improvements in cash and investments (see table, UNE’s Historical Financial Performance, 2008–16).

Where Do We Go From Here?

Operating with a strategic mindset is not sufficient in itself to produce the type of transformational change UNE has experienced. To create a strategic environment, a leader must pass that mindset on to others. From the start, President Ripich understood that her success hinged on her ability to guide existing staff in becoming future-focused, to think about long-term value creation, and to be courageous enough to dream of innovations such as the online college, the study-abroad campus in Tangier, the centers of excellence that focus on UNE’s areas of research, and the competency-based education program.

Not everyone could readily adapt to living with the disruptive changes within the university. Some administrators and faculty left UNE for the slower pace and predictability of other institutions. Those who stayed were encouraged to step outside their industry for professional development, and to think more boldly than educators are sometimes allowed to do. UNE became a hub of innovation, and, as a result, some staff members were recruited by other colleges and universities to bring their strategic vision to other institutions in need of renewal. Some left to become deans, provosts, and even presidents, of other schools.

Despite all these changes in senior leadership, UNE has maintained its momentum. It has continued to grow swiftly and according to plan. Innovation is now part of UNE’s institutional DNA, so that when staff turnover does occur, another strategic thinker is waiting in the wings, ready to fill the void.

Although the president will step down on June 30, 2017, she will leave behind an integrated budget model approach that should sustain future growth, as well as a CBO and other senior leaders who have been trained to think in the same strategic, futuristic way that she did during her tenure.

DANIELLE N. RIPICH is president, University of New England, and NICOLE TRUFANT is vice president, finance and administration.