Let’s say you win the lottery today and, excited about your unexpected good fortune, resign your position tomorrow. What’s the likelihood your institution will have one or two current employees that you’ve seasoned to be ready and able to step into your hard-to-fill shoes?

Pretty low, suggests Patrick Sanaghan, president of The Sanaghan Group, an organizational consulting firm based in Doylestown, Pa. “I’ve been on a lot of board retreats where the leaders talk about the issue,” he says, “but it’s rare to find a campus with a formal succession planning model, complete with an org chart and list of people.

“Succession planning is the rigorous, disciplined process of making sure your internal pipeline has the talent you need to be successful in the future,” Sanaghan continues. “But unlike the corporate sector, which builds 80 percent of its talent from within, higher education tends to bring in people from outside the institution.”

All those executive searches, however, consume valuable resources. “Recruiting has a high cost, when you’re paying 20 to 30 percent of someone’s salary and taking up people’s time to evaluate candidates,” says Chester “Chet” Warzynski, senior advisor, strategic financial initiatives, at Carnegie Mellon University, Pittsburgh, and a consultant to numerous universities (see sidebar, “Starting Gate for Systematic Talent Strategy” for an example of Warzynski’s consulting projects). “When you have a pipeline, you don’t have to do as many searches.”

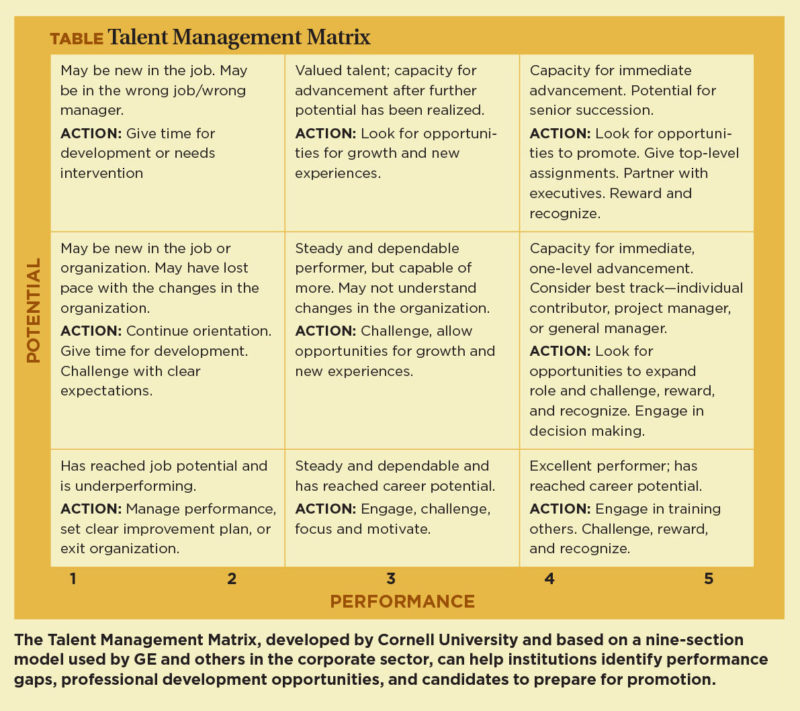

In fact, when Warzynski was director of organizational development at Cornell University, Ithaca, N.Y., six years ago, he estimated the university could save about $2 million on searches annually by instituting succession planning. In addition to saving money, says Warzynski, developing a professional bench of diverse internal talent, based on predetermined ingredients, ensures business continuity by providing backup support and provides incentives for individual employees to grow through professional development opportunities.

“To increase staff productivity while decreasing costs, you have to challenge, develop, and empower people—and succession planning does all of those things,” Warzynski believes.

Spice Up Staff Skills

From personal experience, Melissa Trotta knows what can happen on a campus with limited talent development initiatives. Now associate dean for executive education and strategic initiatives at the Johns Hopkins University School of Advanced International Studies, Washington, D.C., Trotta often saw high-potential co-workers at other institutions walk out the door when they did not see viable career paths internally.

“In many instances, I witnessed talented individuals leaving for positions at other colleges and universities, for opportunities in the corporate sector, or, in some cases, without subsequent positions identified prior to their departure,” she says. “The academic, social, and personal development of students are core functions of a university. By extension, it is ironic that so little personal and professional development of administrative employees takes place on most campuses.”

Trotta herself left one administrative position after seven years because of minimal institutional support and no clear opportunities to advance. She notes, “While I engaged in extensive networking around campus as a means of identifying a more senior role in another part of the university, no such positions emerged, despite more than a year’s effort on my part.”

Stories like Trotta’s can have happier endings both for individuals and the institutions that employ them. To retain your own talent—especially the people specifically recruited for their ability to perform at a high level—lay the foundation for solid succession planning and staff seasoning with these steps.

Engage in workforce planning. Narrowly defined, succession planning focuses on identifying and preparing current employees to eventually move into a handful of key, mission-critical leadership positions, such as CFO and CIO. Both Warzynski and Sanaghan recommend a more comprehensive approach, one that aims to develop leaders at all levels.

“You can create a pipeline to develop talent for key positions while also offering opportunities for growth to other interested employees. A career planning program linked to succession can be a way of covering the entire organization,” says Warzynski.

For Mark Coldren, associate vice president of human resources at Ithaca College, Ithaca, N.Y., succession planning starts with identifying key leadership competencies, no matter what the position. Although Ithaca does not yet have a succession plan, it is moving in that direction by first building solid staffing plans for the future. “Be pragmatic about your core competencies, being careful that they don’t turn into an exhaustive list,” Coldren advises. Characteristics might include such attributes as strategic thinking, ability to manage, business knowledge, and valuing diversity.

Next, he says, “You look at the individual positions. For the chief business officer, for example, what other financial or strategic competencies would you add?” In 2013, Ithaca followed the competency exercise with a workforce plan—looking at the talents and skills within the entire organization as it currently exists and considering what positions and competencies will be needed in the next few years to fulfill the institution’s strategic objectives.

“Ideally, every time you have an opening, you take a step back and look at your plan before immediately posting the same position,” Coldren notes. “Maybe your three- to five-year analysis of talent and needs will point to not filling that same position but absorbing the work somewhere else and creating a new position. And maybe you can promote someone into that new position, for a totally different opportunity.”

“Every hire we make has to be strategic, rather than taking someone just to fill the slot,” concurs Mary Lou Merkt, vice president of finance and administration at Furman University in Greenville, S.C. (see sidebar, “Grooming Possible Successors”).

Identify and assess potential leaders. Merkt encourages her group’s managers to think carefully about every position and how they would fill it should a sudden vacancy occur. Who, for example, acts in a leadership role even if not currently in a position of responsibility?

“When you have that discussion as a group, it’s pretty easy to see right away that you might have great leadership possibilities in IT, for example, but not in finance—or vice versa,” she says. Based on existing attributes, assessments of current and potential skills, and other performance indicators, you can identify ways each employee can maximize his or her potential within your institution.

According to Sanaghan, those who bubble to the top as future leaders—known in the corporate sector as “high potentials”—usually represent the top 5 percent of employees. They require specialized attention, including a plan for developing their readiness skills to move up, through, or across the organization as needed.

When you select the people with the highest potential to succeed campus leaders in the future, Sanaghan offers two points of caution. First, he says, make sure you don’t fall into the trap of “comfortable cloning”—choosing people who are just like you in terms of race, gender, personality, areas of strength, and so forth.

“Also, remember the ‘stylistic invisibles’—the quiet, thoughtful, and maybe introverted people who have the competencies to do a job well but are often overlooked in favor of more charismatic, articulate extroverts. Those quiet and shy people need to be developed, too,” says Sanaghan.

If you don’t currently have anyone on your staff to train or mentor into readiness for a future position, have a plan in place for external hiring. “You have to be prepared to start a search quickly, which means keeping the position description up-to-date, knowing which search firms you’d consider using, and knowing when and where you’ll advertise,” says Merkt. In a succession plan, she advocates including a list of outsourcing solutions, such as firms specializing in interim placements.

Provide a rich menu of development opportunities—and the rationale behind them. As executive director for university organizational and professional development at Virginia Tech, Blacksburg, Va., Lori Baker-Lloyd oversees the university’s Executive Development Institute (EDI) and Management Academy. The former identifies and grooms high-potential senior leaders for the university, while the latter focuses on developing future leaders (middle to upper-middle managers).

For both annual leadership programs, vice presidents and deans make the nominations; Baker-Lloyd’s unit works with a senior management committee to select the participants; and the president’s office provides the funds. The nominating unit, however, is expected to provide funding and support for additional development opportunities.

Since EDI’s introduction in 2008, 121 employees have completed the seven-month program. Of those out of the program more than a year, almost 40 percent have been promoted or taken on expanded responsibilities; only 11 percent have left the university, primarily for personal rather than professional reasons. Baker-Lloyd keeps EDI alumni active and visible by (1) circulating their names when senior leaders form task forces, and (2) asking them to mentor Management Academy participants.

To manage expectations, Baker-Lloyd emphasizes the importance of open communication with EDI participants. “We are very clear about Virginia Tech wanting to develop bench strength, so that we have people trained and ready when opportunities become available,” she says. “We are beginning to emphasize that, by completing the program, they become well-equipped to be viable candidates for future positions—but that there are no guarantees.”

Having researched internal leadership programs within higher education for her dissertation, Melissa Trotta underscores the need for such communication. When interviewing alumni of leadership programs, for example, she discovered some had no idea why they had been nominated to participate. Others thought the program was remedial and meant to address a performance shortcoming rather than expand learning opportunities.

Chet Warzynski encourages colleges and universities to expand beyond formal leadership programs, perhaps borrowing ideas from the corporate sector. Large companies, for example, typically offer job rotation, job shadowing, mentoring, and on-the-job stretch assignments, in addition to classroom training, experiential learning programs, and executive centers that assess and develop potential.

Keep your plans and programs fresh. “Succession plans and competency models need to be live documents, not something you never edit or revise,” believes Baker-Lloyd. That’s why Virginia Tech plans to revisit the competency model it created six years ago and use it as a foundation for its Executive Development Institute curriculum.

“The whole world has changed in that time, providing new challenges for higher education,” she continues. “In addition, we have a new president, which means different expectations and priorities—those related to strategy and leadership. So we might consider adding a few new competencies such as global awareness or agility.”

Warzynski notes that the workforce within higher education currently includes four generations, with more than 20 percent of employees at most institutions now eligible for retirement. Given those demographics, Warzynski suggests adapting your succession plan to welcome not only diversity but also to recognize and respond to the different leadership and learning styles of multiple generations.

Some names on the succession planning list may need to change as well, as newer and younger employees take advantage of development opportunities to increase their visibility and make their mark on the organization.

Review the list at least annually, recommends Baker-Lloyd, looking at which people took on what challenges, how they fared, and the implications. “If people aren’t performing like they were before, is it because they didn’t receive the support they needed? Are they moving in a different career direction?” she asks. “Those things are worth examining, to prevent your high potentials from walking out the door.”

She also would like to introduce “stay interviews” at Virginia Tech, as one means for managers to communicate the plans they have in mind for those exhibiting high leadership potential. Baker-Lloyd saw the benefits at her previous organization, which required its senior leadership team to regularly conduct stay interviews with the people the group identified as key talent, with the hope of averting exit interviews in the future.

Rather than simply telling an employee, “You’re on a succession planning list,” and walking away, the leader remains responsible for managing and developing that talent. “The senior leadership team uses the stay interviews to identify upcoming professional development opportunities, review previous opportunities, discuss what the group has in mind for stretch assignments, and converse about the person’s value to the organization,” Baker-Lloyd says.

Identify Ideal Ingredients

In some institutions, the president’s office maintains a written—and confidential—list of people considered the prime internal candidates for key leadership positions. While such a list isn’t a required component of succession planning, the demonstrated commitment from top leadership certainly is.

Without the ongoing support of senior leadership—appointing potential leaders to special project teams, sharing their expertise with up-and-coming employees, and talking about careers on campus—succession planning will have little chance of taking root. Plus, administrative funding is often needed to undertake formalized development activities and programs.

Because succession planning overlaps with leadership development, career planning, and performance management, you’ll also need HR support to help integrate those various elements. Using a talent management database or module, for example, HR personnel can easily track an individual’s competencies, skills, assessment results, and growth experiences and link that information to a personal development plan.

“Ideally, the HR person should look at all performance reviews and identify those with the highest ratings. Then the HR person and the manager need to have some conversations about how to get that high-performing employee ready to take the next step,” says Mark Coldren.

Finally, supervisors and managers must frequently initiate career-oriented discussions with their employees. “According to the Center for Creative Leadership, the No. 1 way to develop people is through what they’re doing right now—which means you must have good supervision,” says Sangahan. “For example, are your VPs reviewing goals for staff every week? Providing feedback? Asking questions? Offering strategy and support? The point is not micromanagement but to better direct talented and dedicated people through supervision.”

With many baby boomers positioned to retire within the next five to 10 years, such conversations are crucial for shaping the next generation of leaders. Less-experienced leaders will need the time to develop a skill set for the future—one that may look different in terms of the talents and competencies valued in their institutions today.

“Everyone gets nervous about retirements in key positions, especially when people have been at their institutions for 30 or 40 years,” Coldren observes. “But if you are intentional about leadership development and have the foundational pieces of succession planning in place, those retirements really represent an opportunity for people to grow.”

In other words, all should be well. So, go ahead and buy that lottery ticket.

SANDRA R. SABO, Mendota Heights, Minn., covers higher education business issues for Business Officer.