While the Great Recession has technically been over since the summer of 2009 and stocks have generally been rising ever since, other negative factors remained. High unemployment, stagnant wages, and slower-than-expected overall economic growth caused a great deal of volatility in financial markets and left most American consumers in the doldrums between FY09 and FY13.

But in the spring of 2014, the economy suddenly began to take off. Gross domestic product (GDP)—the value of all goods and services produced, adjusted for price changes—shifted from a decline of 2.1 percent in the first quarter of 2014 to a robust gain of 4.6 percent in the second quarter. The unemployment rate dropped from 7 percent during fall 2013 to 6.1 percent by the end of June 2014 and continued to fall in the months thereafter. Many other indicators—from industrial production to residential construction—suggest that the economy has finally begun to regain the footing lost during the recession.

The good economic news soon launched U.S. and international equity markets. During the period between July 1, 2013, and June 30, 2014, the U.S. stock market, as measured by the Standard and Poor’s 500 index, jumped 24.6 percent. Foreign stocks, based on the MSCI ex-U.S. index, followed suit with a 23.3 percent gain. Stock markets were particularly resilient, rising despite several rough patches during FY14: a 16-day federal government shutdown in fall 2013 that economists estimate cost $24 billion and lowered economic growth in the second quarter of the fiscal year by 0.6 percentage points; continued below-average economic growth in much of Europe and growing worries about the Chinese economy; Russia’s conflict with Ukraine, which rattled many emerging markets; and the winding down of the U.S. Federal Reserve’s “quantitative easing” program, credited by many analysts with propping up the stock markets for much of the past three years.

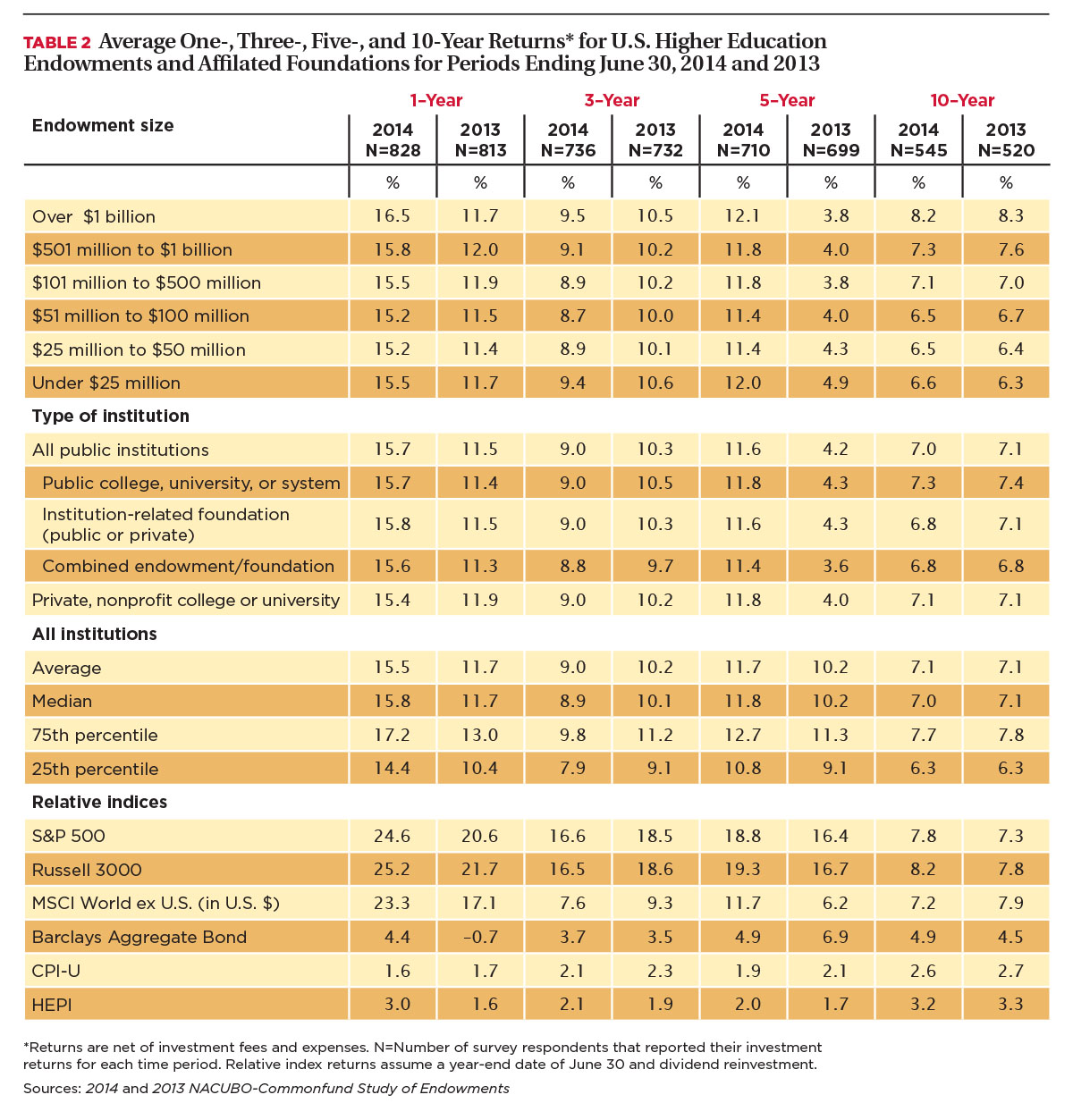

Growing investor confidence in the U.S. economy also benefited college and university endowments, which rocketed to a 15.5 percent average investment gain (net of fees) in FY14, according to the 2014 NACUBO-Commonfund Study of Endowments (NCSE). The FY14 performance was nearly 4 points higher than the average reported for FY13 (11.7 percent) and the best performance since FY11’s 19.2 percent. And continued economic growth during the first half of FY15 suggests that the upward momentum in endowment performance may continue.

This overview of the results of the 2014 NCSE takes a look at the investment strategies institutions used to achieve their results, and examines the fiscal and other challenges endowment managers and other higher education leaders are facing in FY15 and beyond.

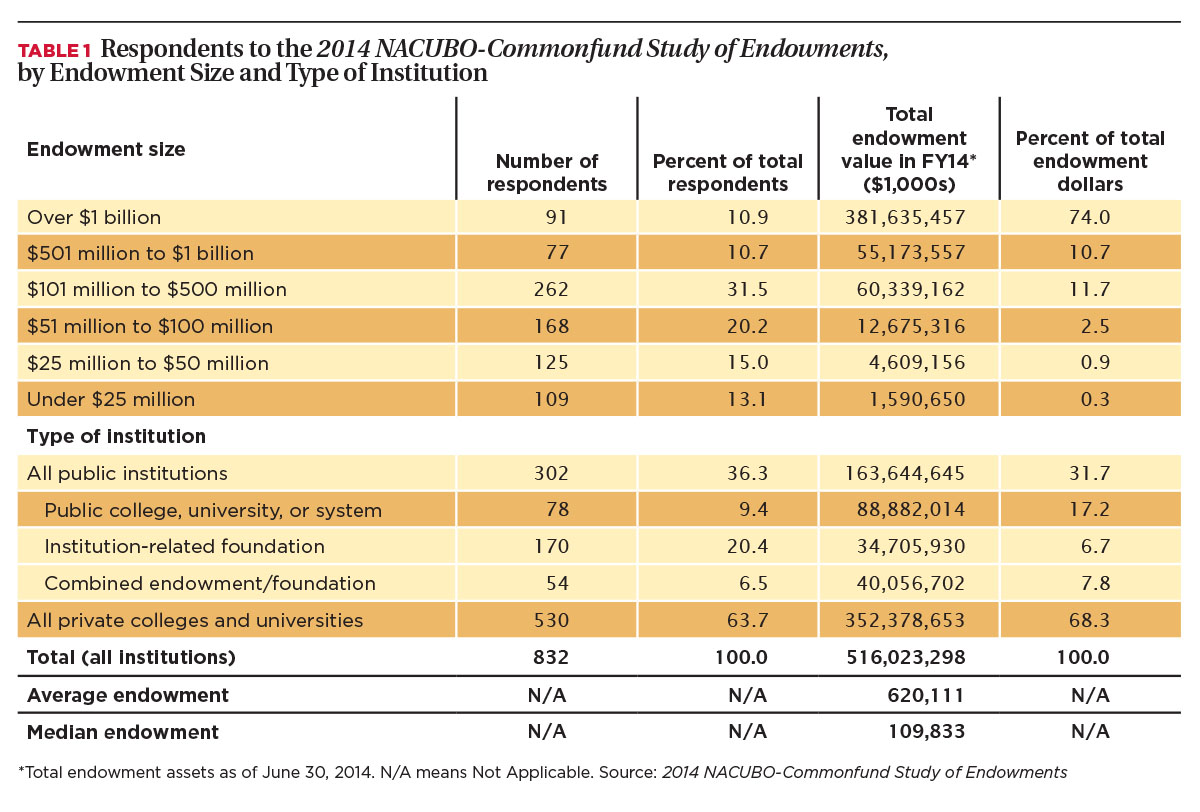

Once Again, Fund Size Matters

Eight hundred and thirty-two American colleges, universities, and higher education foundations participated in the 2014 NCSE. Collectively, these institutions held a total of $516 billion in endowment assets as of June 30, 2014 (see Table 1). Nearly 11 percent of the participating schools had total endowment assets of over $1 billion, while approximately 13 percent had funds that were less than $25 million. The average endowment among all these participants was about $620.2 million, while the median was $109.8 million. Institutions with over $1 billion in endowment assets accounted for 74 percent of the total endowment dollars among the 2014 NCSE participants.

While endowments of all sizes benefited from the favorable market conditions in 2014, the greatest beneficiaries appear to have been the largest ones. The over–$1 billion funds reported an average one-year net return of 16.5 percent, nearly 5 percentage points higher than the prior year (see Table 2). Returns for all other size categories were otherwise clustered around a narrow range between 15.2 percent and 15.8 percent. This is a sharp reversal from FY13, when the average one-year return for endowments below $25 million (11.7 percent) was nearly identical to that of the $501 million to $1 billion (12 percent) and over $1 billion (11.7 percent) categories.

More importantly, for the largest endowments, the average annual return of 8.2 percent for the 10-year period ending June 30, 2014, was 1.6 percentage points greater than the average returns (6.6 percent) of the smallest-sized funds, suggesting significantly greater long-term performance during the past decade for the larger funds.

Benefiting from U.S. equities. Despite the differences in performance by endowment size, both large and small endowments benefited greatly from their allocations to U.S. equities. The $1 billion endowment at Baylor College of Medicine, Houston, for example, achieved a 19.5 percent investment gain due to “tactical overweight for U.S. equity assets and tactical underweight for international equities,” according to William D. Walker, vice president and chief investment officer. “We also benefited from an absence of hedge funds in the portfolio.”

The $144.4 million endowment at Augustana College, Rock Island, Ill., also benefited from its equity positions. This fund gained 15 percent during FY14 by “increasing our weighting of equities, both domestic and international,” says David A. English, chief financial officer and vice president of finance and administration. “We also decreased our proportion of fixed income in FY14, and that clearly helped our returns.”

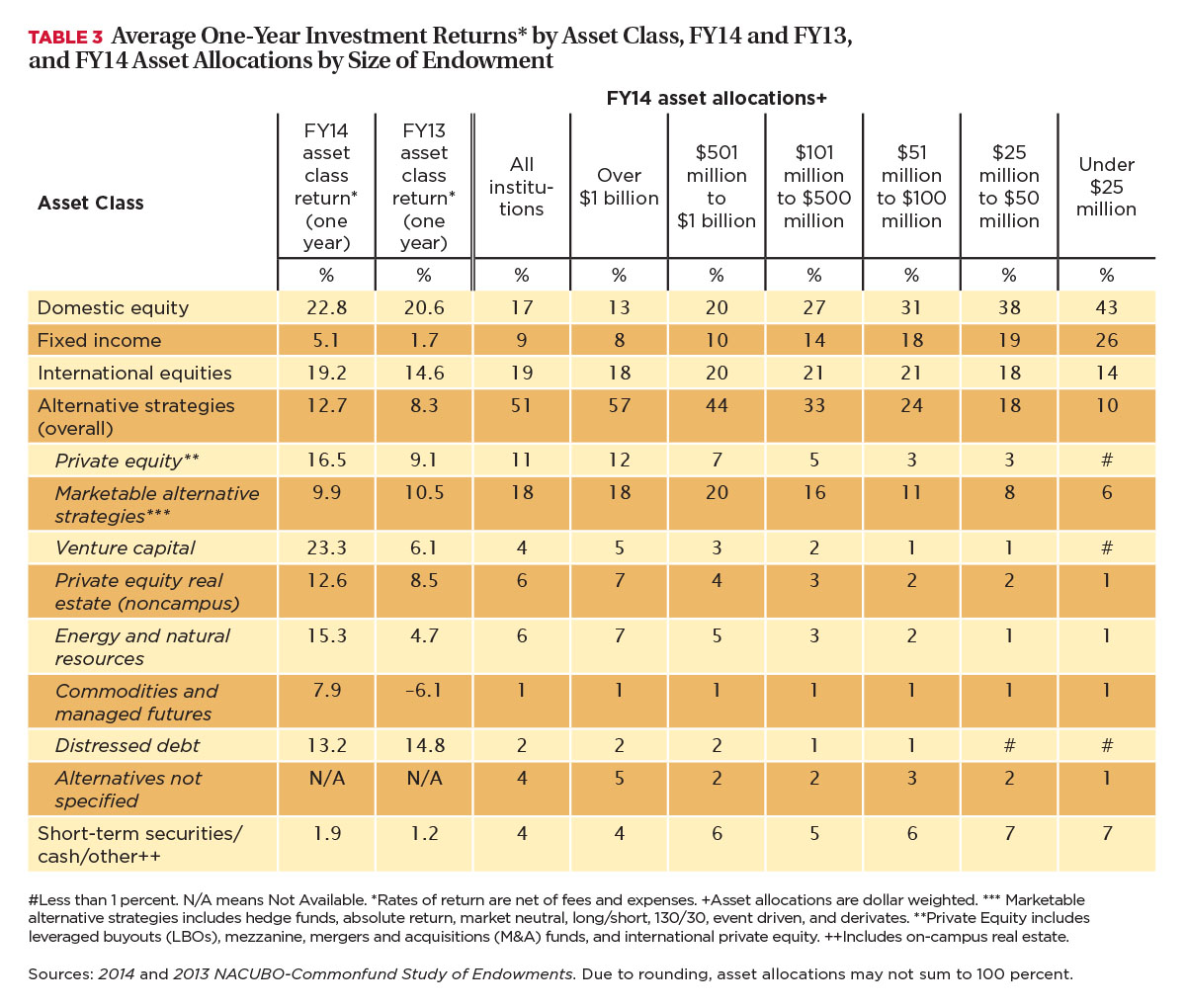

De-emphasizing bonds and alternatives. While all institutions benefited from the rise in stocks, a reduced emphasis on fixed income assets by larger endowments may have contributed to the difference in overall performance by size. As Table 3 shows, the largest endowments had only 8 percent of their total assets in bonds (domestic and foreign collectively), while funds between $101 million and $500 million had 14 percent, and those below $25 million had 26 percent. Bonds in FY14 returned 5.1 percent for endowment portfolios, compared with a 22.8 percent gain in domestic stocks and 19.2 percent rise in non-U.S. equities. “In 2012, bond yields were near historic lows,” explains Scott S. George, president and chief investment officer for Mason Investment Advisory Services Inc.

“This limited the upside, but not the downside, of investing in bonds.” Mason’s analysis of the interest rate environment led to a temporary reduction in the percentage of assets invested in long-term bonds in their clients’ model portfolio. “We modified the allocation due to the historically low–bond yield environment. But we view this shift from fixed income to equities as temporary and will revert back to the allocation’s long-term mix when interest rates rise to a predetermined level.”

In the meantime, bond allocations may have reduced slightly the overall returns generated by smaller endowments, at least in the short run. “For several reasons—correlation benefits and downside protection being the most prominent—we retained a significant fixed income allocation,” says English. “While that would have helped us if the market had experienced an FY08–like drop, it pulled down our portfolio return in FY14 when U.S. equities provided outside returns. Of course, that’s part and parcel of a diversified portfolio strategy.” (See sidebar, “A Prudent Approach to Fund Management.”)

Maintaining a Long-term Outlook

As English suggests, keeping an eye on the longer-term horizon is just as important in an up market as it is when markets are declining—even when one or two asset classes underperform in an otherwise upward trend. After all, as the recent past shows, markets often change suddenly. While financial returns reached new heights by the end of FY14, they appeared to run out of fuel in the first quarter of FY15. Stocks were down in the early part of the fiscal year, due in part to falling oil prices, which had the potential of depressing energy companies’ returns as well as returns in some emerging markets. As a result, “international equities provided negative returns in the first three months of FY15, and U.S. small-cap equities dropped significantly, while U.S. large-cap equities remained stable,” says George. “These are just a few examples that provide a reminder of the importance of diversification and ‘staying the course’ during inevitable changes in asset class leadership.”

English agrees wholeheartedly with this advice. “We continue to maintain a diversified portfolio, with portions allocated to real estate, commodities, hedge funds, and private equity, in addition to more traditional fixed income, and domestic and foreign equities,” he says.

While equities shook off these concerns and resumed their ascent in late calendar year 2014, investors faced a number of challenges in the early part of FY15: continually weak economies in Japan and much of Europe; conflicts in Ukraine and the Middle East; and steep plunges in oil prices that could further dampen economic growth in a number of emerging markets. The combined factors caused U.S. stocks to fall more than 7 percent from the highs set in the early fall of 2014 before bouncing back in the early winter.

On the other hand, continued good economic news for the U.S., such as strong growth in GDP in the July-to-September 2014 period and slower but still respectable gains in GDP in the final quarter, have caused many analysts to predict that the nation’s economy may continue to expand, which helped U.S. markets recover some of the ground lost in the early fall sell-off.

Sharp upward and downward movements in the stock markets suggest that, while markets may continue to rise in FY15, there will be much more volatility going forward than there was during the latter half of FY14. Renewed prospects of wider market gyrations may have endowment managers poised to make adjustments in their portfolios. In this type of environment, manager selection becomes even more important. “Manager and strategy selections in several expanding asset classes will be key for us going forward,” Walker says. “We’ll be reviewing underperforming managers in a few strategies.”

But, as English points out, any introduction of new asset classes has to be very carefully considered. “I’d be careful of chasing after the next ‘hot’ thing, and shy away from investing in an asset that you don’t understand,” English says. “If any institution is considering a new asset class, the investment committee should ask why it wants to add it. If the institution can’t clearly articulate the reason, then don’t add it.”

George notes the advantage of maintaining a long-term outlook regardless of current market conditions. “It is important to note that the purpose of a diversified portfolio is to maintain asset classes that move in different directions [non-correlated asset classes] over a variety of market environments to reduce volatility,” he says.

Endowment managers are well advised to maintain a focus on the longer term despite possible short-term changes in the economy or other issues. “I think we have to rely on some historical themes as a guide,” English says. “And that long-term history has shown time and again that ownership—equities—provides greater returns over a long-term average—particularly in deep, efficient markets; and that diversification across asset classes and over time pays; and short-term volatility is often rewarded over the long term.”

George echoes these sentiments. “Depending upon the current climate, investors often focus too much on either risk or return,” he says. “We have to keep in mind that a key goal of endowments is to achieve a level of return that is adequate to further institutions’ missions at an acceptable risk level. Over the long term, it is important to keep in mind that the best way to achieve this goal is to have a disciplined strategy and not overreact to short-term trends.”

KENNETH REDD is director, research and policy analysis, NACUBO.