When Hurricane Katrina pummeled and flooded much of the Gulf Coast in 2005, the New Orleans-based Louisiana State University (LSU) Health Sciences Center went underwater. Seven of the nine teaching hospitals used for student clinical rotations closed suddenly, and students and faculty evacuated, along with most of the city’s residents.

While hospitals and local businesses could simply close their doors until cleanup and recovery efforts allowed them to reopen, that wasn’t an option for the Health Sciences Center. Federal funding required that classes continue, even though the necessary hospitals and teaching buildings had been lost. “We had to do something, or we’d lose our students,” says Larry Hollier, chancellor of the Health Sciences Center, who served as dean of the medical school at the time of Hurricane Katrina.

Center leaders scrambled and innovated to keep their schools open, and they have spent much of the ensuing years rebuilding and redesigning policies to prepare for future disasters. “The main thing is to recognize that a disaster can occur; they happen everywhere,” Hollier says. “Administrators need to be prepared for what they would do.”

Like the Health Sciences Center, other colleges and universities have weathered hurricanes, tornadoes, wildfires, and myriad natural disasters in recent years. In many cases, leaders have emerged from those experiences wiser and more prepared for the unexpected. More than other types of business interruption, natural disasters have the potential for broad, immediate, and immense destruction, sometimes with long-term disruption. As such, natural disaster preparedness can be an effective vehicle for business continuity planning.

“There are so many things we need to prepare for, but the emergency we prepare for isn’t always the one we have to deal with,” says Joyce Lopes, vice president for administration and finance at California State University, Sonoma, who managed operations through a wildfire in 2017 and a bus fire at her former institution that resulted in 10 deaths.

College and university officials who have weathered disasters say that their experiences have yielded important lessons that will better prepare them for the next unexpected event. A closer look at some of these insights can help other higher education leaders as they prepare for the future.

Messaging Matters

When the Camp Fire burned 153,000 acres in Northern California in late 2018, California State University (CSU), Chico, was the closest higher education institution in its path. The flames never reached the campus, but poor air quality due to smoke forced administrators to close the facilities for several days. When the decision was made, leaders issued direct, informative, and compassionate communications, says J. Marvin Pratt, director of environmental health and safety at Chico State.

“Our campus community, students’ families, and Chico in general looked to Chico State to be a source of information, as well as comfort, during the very uncertain first few days,” Pratt says. He recommends messaging faculty, staff, students, and students’ families and posting those messages and updates on social media channels, when appropriate. Someone should also be in charge of continuously updating messages, “even if there’s nothing to update,” Pratt says, so your audience knows you’re paying attention and that they’re valued.

Even the messages sent out from the very beginning of a crisis can communicate business continuity, says Scott Hummel, executive vice president and provost at William Carey University in Hattiesburg, Miss., which was hit by an EF3 tornado in 2017 that damaged 49 of 50 buildings on campus, including six that were ultimately demolished. Even though the William Carey campus was closed temporarily, all courses continued by meeting either online or in off-campus locations. Leaders carefully worded the message: “‘Campus is closed, university is open.’ That was a continuity message,” Hummel says. “If students begin to fear that they have nowhere to go, they’ll leave.”

When the tornado hit, William Carey had about three weeks left in its winter trimester, and registration for the following term was underway. Rather than delaying registration or halting classes, university leaders found ways to move forward. “Students needed to be able to register to show we were prepared for continuity,” Hummel says. “We actually had an enrollment increase in the term after the tornado.”

Put People First

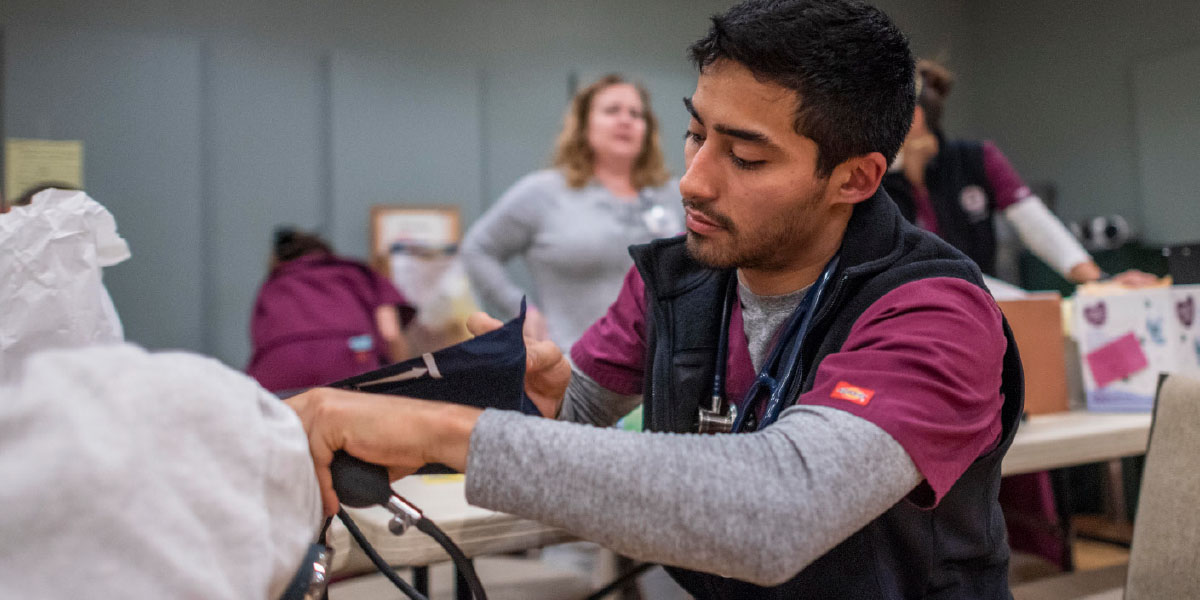

Business continuity is crucial for moving forward after a crisis, but institutions that recover successfully focus first on meeting the needs of their faculty and students. For example, Houston Community College serves a 500-square-mile area with more than 20 locations in and around Houston. When Hurricane Harvey hit Southeast Texas in 2017, an estimated 70 percent of the 1,800-square-mile Harris County was covered by one-and-a-half feet of water and an estimated 136,000 structures were flooded.

While the college’s facilities were not flooded, 10 percent of employees were affected personally, as were 60 percent of students. “Our focus was on what we needed to do for our employees and students,” says Janet May, chief human resources officer at Houston Community College.

Each department had a roll call system or text chain set up to check in with employees. “We went through the text chain twice a day for several days, and that helped us know who on our teams was affected,” May says.

Aside from keeping track of employees and their needs, Houston Community College set up a Disaster Recovery Center to make it easy for employees and students to find the resources they needed, such as food and clothing drop-offs and emergency services updates. Because the start of classes was delayed for two weeks and no employee training was being offered, learning and professional development staff were able to run the Disaster Recovery Center.

Houston Community College initiated a new leave policy to provide paid leave to both part-time and full-time employees during the crisis, so they could manage personal losses without giving up income. Employees were allowed to apply through a simple application process for up to 10 days of paid leave for the crisis, which could be used for up to one year. The college also instituted up to five days of “emergency leave,” a new leave category put in place for both part-time and full-time employees.

Houston Community College paid all part-time employees for 15 hours during the week the college was closed and put together a disaster relief fund for full-time employees, which was paid for by auxiliary funding. A committee managed the fund and provided relief funds of either $250 or $500 to more than 385 employees, for a total of almost $170,000.

Move Quickly

In the wake of a disaster, the ability to make quick decisions and act nimbly can be the difference that enables business continuity. When the tornado hit William Carey and it appeared that some buildings might collapse, leaders quickly decided to close the campus while keeping the university open through online and off-campus classes. “We could have used more time, but we had to project confidence and remain open,” Hummel says. “Any delay could have created panic.”

Sonoma State’s president lost her home in the North Bay fires in 2017. Fortunately, the university had policies in place to identify people to fulfill leadership roles in its Emergency Operations Center. “It’s important to identify three or four people who can fill any leadership roles in case of emergency,” Lopes says.

At Chico State, the Camp Fire was an unprecedented event for the institution and the CSU system. “Nestled in the Northern Sacramento Valley, Chico State is generally not susceptible to natural disasters. We’re hundreds of miles from a coastline, the university doesn’t sit on a fault line, and tornadic activity is nearly unheard of here,” Pratt says. “While the university had not identified this specific threat, and thus had not prepared specifically for this disaster, Chico State was prepared to take action and provide messaging to our campus community, parents of our students, and the Chico community as a whole.”

Maintain Schedules When Possible

Even as natural disasters rage, colleges and universities must continue operations. When Sonoma State closed due to the North Bay fires in 2017, the federal government sent a letter to alert administrators that the college’s financial aid funds would be in jeopardy if it missed too many days, Lopes says. While Sonoma State was back on a regular schedule within 10 days, the university now has agreements in place with a nearby community college and office building that would allow it to rent classroom space if needed.

“We were the first in the county to reopen, and getting back on schedule really helped establish hope and show that we were starting to move into recovery,” Lopes says.

The day after Hurricane Katrina hit, the deans of all the schools in LSU’s Health Sciences Center met to discuss how to continue operations, Hollier says. Each dean found a place to continue his or her classes: The nursing school went to movie theaters, and the dentistry school used extra space at the agriculture school.

Because so many students and faculty had evacuated to Baton Rouge, La., and were sleeping on friends’ couches around the city, medical school leaders knew they needed to acquire stable housing for students and faculty, or the school would lose students. Somebody found a ferry with 1,400 beds for rent online, and Hollier and his staff talked the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) into paying in advance for a six-month lease for the ferry and crew, which was $37.5 million. With classes held in various locations around Baton Rouge, La., and 1,400 students and faculty living on a ferry docked on the Mississippi River, the Health Sciences Center’s six schools all opened four weeks after the storm with 95 percent attendance.

Prepare Staff for Contingencies

Before the 2017 tornado at William Carey, the university had already been affected by flooding after Hurricane Katrina. Because of that experience, faculty had been instructed that they should always be prepared to turn their classes into online classes. “They believe us now more than ever,” Hummel says.

Not every course works online, however. For instance, the medical school at William Carey needed labs and classroom space following the tornado. Fortunately, the University of Southern Mississippi, also in Hattiesburg, Miss., had just completed a new building and had a completely empty building on campus—and because of an existing relationship between the two schools, USM officials offered the space to William Carey. The medical school was able to relocate in five days, missing just three days of classes, Hummel says.

It isn’t possible to plan for every scenario, but ensuring that classes will be able to continue online in the case of a disaster is an important step. At LSU’s Health Sciences Center, another important step for continuity is establishing contracts or agreements ahead of time with hospitals across the region each year, even if students and medical residents aren’t assigned to most of those hospitals.

That’s because the government pays medical residents and faculty at teaching hospitals—but only if the medical school has a contract in place for those services by the first of July of each year. When Hurricane Katrina closed seven of the nine teaching hospitals with which LSU had contracts, there was no way to get residents paid if they moved to other hospitals. “We got approval overnight to get them moved, but there was no way to pay for them,” Hollier says.

At the time, LSU “burned through cash” to fund its residents and later petitioned the government for a waiver to receive payment, despite not having contracts in place by July 1. Today, the university maintains preexisting contracts or agreements with a number of hospitals in various locations, which allows them to change the number of residents at those hospitals during the year if needed.

Know the Resources Available

When a natural disaster hits, most communities band together to help each other recover. Colleges and university leaders who have weathered such storms say those community partnerships have helped their institutions pull through, but they recommend establishing partnerships and identifying resources before a disaster ever happens.

For instance, William Carey and its neighboring institution, the University of Southern Mississippi, had a strong collaborative relationship in place before the 2017 tornado. In its immediate aftermath, USM’s president toured the William Carey campus, and after seeing the devastation he met with his cabinet to discuss how they could help. Not only did USM offer an empty building for William Carey’s medical school to use, but it also offered extra dormitory space for about 300 displaced William Carey students, as well as additional classroom space. A large local church also contacted William Carey to offer classroom space.

Every quarter, Missy Brunetta, director for emergency services and associate risk manager at Sonoma State, meets emergency managers across the region to stay involved in discussions about potential risks and managing them. “I’ve been here 18 months and have already dealt with three countywide emergencies—fire, smoke, and flooding,” Brunetta says. “This is just the way we have to think about operating; managing risk and staying in conversation with emergency management agencies need to be front and center.”

Institutions that are part of a larger university system have built-in supports that become crucial during a disaster. “We leaned on our sister campuses for guidance as to how to navigate this crisis, particularly Sonoma State, which was impacted by its own fire in October 2017,” Pratt says. “Many California State University campuses also provided additional uniformed officers to help our own university police provide patrols throughout Paradise, Calif., in Chico, and on campus.” Paradise, a town east of Chico, was hit hard by the fire.

Establish Policies That Meet Needs

Desperate times call for desperate measures, and institution leaders need to understand both the needs of their community and their own policies in order to make changes swiftly and properly. For instance, at Houston Community College, where leaders instituted a new emergency leave policy for all employees, including part-timers who normally had no paid leave, “we were working through the leave policy as the storm was going on,” May says. “You really need to know your employee population; if you don’t know what the needs will be and can’t be nimble, it will be very hard to respond.”

Because Houston Community College is not a state employer, it was able to make some quick changes without going through red tape. “Really know what your policies are and what you can and can’t do without approval from your board,” May advises.

At Chico State, some employees’ lives were devastated while others were hardly affected by the fire, which necessitated the need for a leave-sharing policy. “Our workforce demonstrated an overwhelming desire to help in the immediate aftermath, and having a policy that allows employees to donate leave to others in need was something we immediately developed and adopted,” Pratt says.

At the time of the fire there were no existing policies about campus closures due to air quality, so Chico State and other CSU institutions are now working toward creating clear guidelines. For instance, the new policy will clarify which employees are subject to being called in during a campus closure, their compensation structure, and the process by which to track and document their hours worked, Pratt says.

And while Chico State didn’t alter any employee benefit policies, leaders successfully reached out to benefit providers to ask for flexibility and expansion of various programs. For example, the institution’s employee assistance program provider approved a temporary increase in the number of free counseling visits offered to employees and their family members.

Unexpected Blessings

No campus leader hopes to experience a natural disaster, but those who recover successfully from such experiences find that, through reflection, they can see how “disaster can turn into a blessing,” says William Carey’s Hummel. “Faculty and students drew closer together, news of the tornado brought more awareness to the university, and we were able to do some different things with our facilities [through rebuilding].”

Such experiences can also ensure that institutions will be prepared for future disasters. For instance, after Hurricane Katrina devastated LSU’s Health Sciences Center, the institution’s University Medical Center building is now “a hardened facility,” meaning it includes generators and appropriate storage for fuel so it can be self-contained for a full week. “We also have prepositioned fuel at the outskirts of New Orleans to readily supply to the facility, students, and staff if needed,” Hollier says. “All buildings have generators located on the second floor or above.”

NANCY MANN JACKSON, Huntsville, Ala., covers higher education business issues for Business Officer.