The statistics about tuition discounts don’t lie … but neither do they tell the complete story.

The 2014 NACUBO Tuition Discounting Study (TDS), which reports final discount data for the 2013–14 academic year and preliminary data for 2014–15, indicate two clear and continuing trends:

- Tuition discount rates and average institutional grants to freshmen continue a slow but steady upward march.

- Net tuition revenue remains stagnant, showing a slight uptick in current dollars, but a decline in inflation-adjusted value.

Each year, the TDS measures tuition discount rates, net tuition and fee revenue, and other indicators of institutional grant aid awards provided to undergraduates who attend four-year private, nonprofit (independent) colleges and universities. This year, 411 private institutions participated in the study.

While helpful in assessing the total situation, the two trends tracked by the TDS do not provide a complete or balanced picture of the current reality in tuition discounting. Leaders of private, independent institutions continue to struggle with the perennial question: How can we adopt enrollment and discounting strategies that fill classrooms, keep the lights on, and provide stable net tuition revenue, while still providing access to financially strapped low- and middle-income families, as well as merit aid to the high-performing achievers who maintain academic quality?

To dig deeper into the data, Business Officer interviewed four survey participants, whose answers reveal several surprising strategies for coping with a dwindling supply of high school graduates, stiff competition from public and other private institutions, and an intense focus by families on cost and value.

In the Sweet Spot

To stay affordable, Lycoming College, Williamsport, Pa., is keeping net tuition revenue at a standstill. “Net tuition revenue is flat and possibly declining, even though there is a lot of publicity about gross tuition increasing,” says Jeff Bennett, vice president for finance and administration, chief financial officer, and treasurer.

“Right now, we’re not in a position to push net tuition revenue,” he continues. “The cycle we’ve been in is to hold net tuition revenue steady to remain affordable and allow students to come to Lycoming College. We’ve decided that we have the financial strength to keep that option open to low- and middle-income families. Our trustees and president, staff, and faculty feel strongly about staying affordable for those students.”

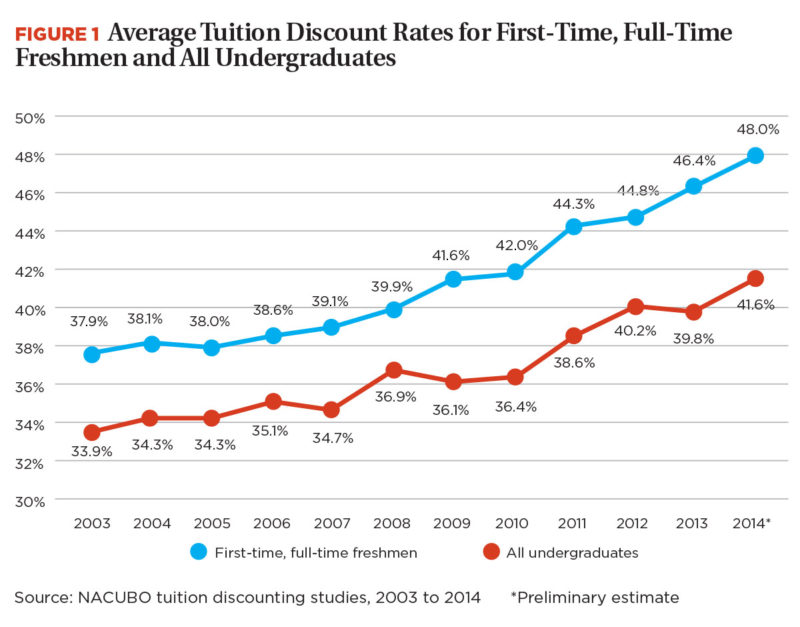

Lycoming awarded $27.5 million in aid to students in the 2014–15 academic year, during which tuition and fees were $34,000. The discount rate hovers around 50 percent. A discount rate at this level is typical of institutions that took part in the NACUBO survey. As Figure 1 shows, between fall 2003 and fall 2014, the average discount rate for all undergraduates jumped from 33.9 percent to 41.6 percent, and the average rate for full-time, first-time freshmen increased from 37.9 percent to 48 percent. “Our tuition discount rate has increased slightly, based on the need we’re seeing from middle-to-low income families and first-generation students,” Bennett points out. “That population is being pinched. We want to make sure that Lycoming is still an opportunity for them.”

Bennett classifies the current total enrollment of 1,300 as “right around the sweet spot,” indicating that leaders currently have no desire to expand too much beyond that. “When you grow, you have to build more buildings and hire more faculty and staff, which we’ve made a conscious decision not to do at this point.”

Like other institutions, Lycoming is seeing a declining number of traditional college-aged students in what has been its central recruiting area—Pennsylvania, New York, New Jersey, and Maryland. “We’ve stretched our boundaries, not only domestically but internationally, in an effort to attract students from other ethnic backgrounds and geographic locations,” explains Bennett.

New partnerships with KIPP and YES Prep, organizations that provide high school seniors from low-income families with an opportunity to attend a liberal arts college, have added 70 to 80 students and increased diversity. All freshmen at Lycoming are receiving institutional grants.

Bennett praises the investing decisions of the college’s leaders, who have managed to create an endowment that currently tops $210 million. “We don’t have to pressure our students for significant additional net tuition revenue,” he says. “We can keep it affordable and support the college’s operations through our investments. Based on our endowment, we don’t have to rely as heavily on tuition as other schools might.”

Moving Target Enrollments

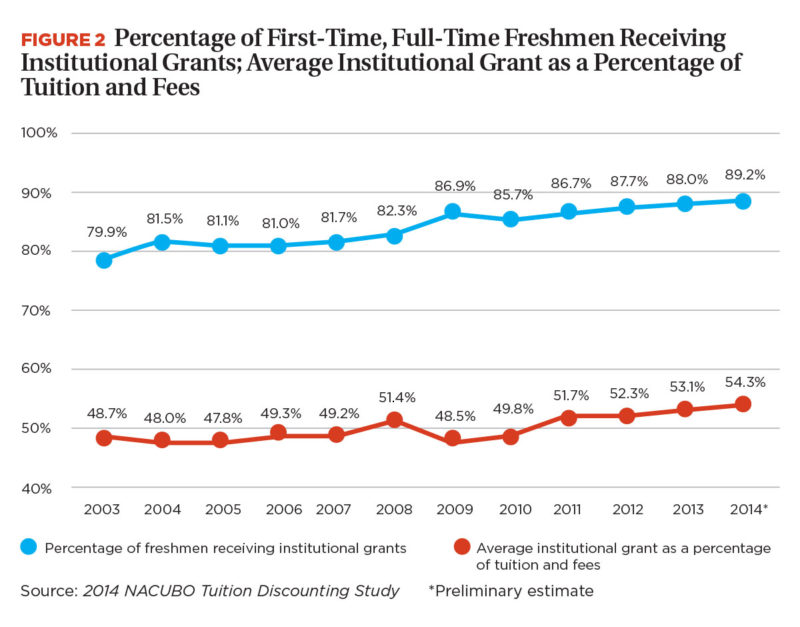

It’s not just superstars who get institutional grant aid, as Figure 2 points out. In 2014, an estimated 89 percent of full-time freshmen received grants, and the average grant covered more than 54 percent of the average tuition and fee “sticker” price. Despite the rising shares of students getting grants and average awards, many schools have struggled to meet their enrollment goals. To counteract smaller entering classes, Concordia College, Moorhead, Minn., is zeroing in on students who may have received scant attention a decade ago.

“As you look at the profile of the students, merit versus need, the enrollment division with its financial aid partners has intentionally directed need-based aid to attract the midrange of our academic profile,” says Linda J. Brown, vice president of finance and treasurer. “We’ve had some success with that. We’ll continue to pay attention to that strategy by looking at the second and third tier of our academic profile and capturing a portion of those applicants. We try to be sure to package need-based aid to be competitive with publics and pull those students here.”

Concordia’s freshman class, which typically numbers 600, came in at 540 students last year, 98 percent of whom received institutional grants. Institutional grants as a percentage of fees average 48 percent. “Our competition is very diverse, both public and private,” says Brown, who believes merit aid has become a driving force in the decision-making process. “The sticker price might not be the sticking point,” she says. “The amount of the award is more important than the net price to some individuals.”

She recounts cases in which families have been swayed by a higher aid package, eventually choosing a comparable college even though the net price cost thousands more. “Does the general public know the role that institutional aid plays and how critically important it is to think about net price when making its decision?” Brown asks. “That’s the challenge.”

In the past five years, Brown has noticed a change in what was formerly “a very high yield rate [the percentage of admitted students who actually matriculate].” The decreased conversion rate, which is now more in keeping with competing institutions, is requiring Concordia to expand its applicant pool.

“To hit our target, we have to increase the number of applications, and we are in a part of the country at the bottom of the trough in terms of the number of high school graduates, which increases the competition for a smaller pool of students,” she says.

Brown has also spotted a decidedly different pattern of decision making by students. “They’re taking longer to make their college decisions,” she says. “I’ve been in higher ed for 30 years. I used to be able to pretty much predict—and be within a handful—what our fall enrollment would be, by late March or early April. That is becoming less possible. What we’ve seen is an extended pattern for college-choice decisions.”

Data Drive Enrollment

Total tuition and fees at the University of the Ozarks in Clarksville, Ark., are holding steady at $23,750 for fall 2015, reports Jeff Scaccia, vice president for finance and administration.

“Our families are concerned not only about cost, but also about debt loads,” he emphasizes. “We’re trying to keep our tuition flat and to communicate to those students what aid is available from the institution and what might be available from other sources. We felt that it was something we needed to do, given the clientele we serve.”

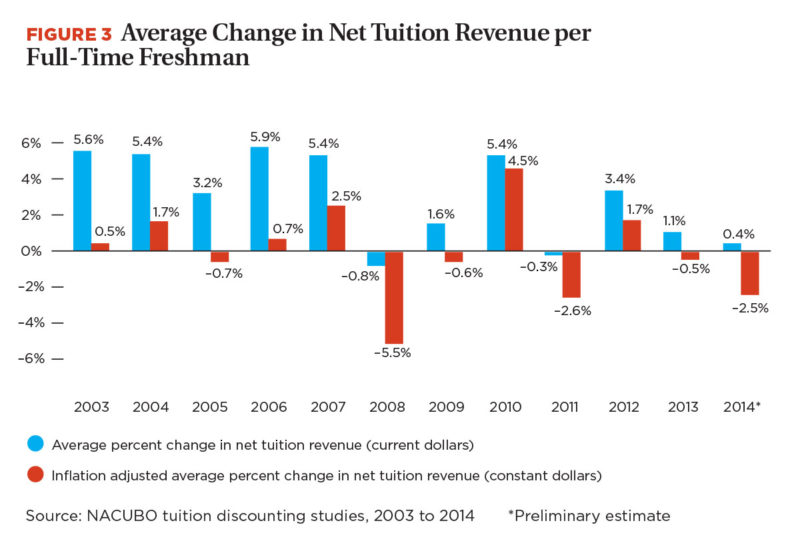

Students’ increasing inability or unwillingness to pay the full tuition price, the overall economy, and recruiting data factored into the decision to keep tuition stationary. However, keeping tuition steady while raising the number and amounts of grants can have a detrimental impact on net tuition revenue, as Figure 3 reveals. On average, net revenue received from first-time freshmen is projected to have grown only 0.4 percent in current dollars between fall 2013 and 2014, which equates to a decline of more than 2 percent when adjusted for inflation. When adjusted for inflation, overall net revenue received from freshmen has been flat over the past 12 years.

These trends make understanding individual student-level data and circumstances more important than ever. “We’ve been trying to understand our students, make our operations as efficient as possible, and use data in a way that makes our enrollment processes more efficient and effective so that we can better identify the students in our recruitment pool most likely to be interested in our institution,” Scaccia says. “If we can better understand their needs, the better we will be in enrolling a class that meets our planned discount rate.”

For fall 2014, the overall discount rate was 50.9 percent, up from 49 percent. The freshman rate was 59.5, down from 63.3. “We’re slowly trying to decrease our discount rate while staying aware of our students’ needs,” he explains. “We’ve been successful the last couple of years. This past year, we increased our incoming class and improved our retention rate.”

The fall 2014 class attracted 171 incoming students, compared to the fall 2013 class of 159. Scaccia expects the 2015 class to be about 200 students. “We’ve made an effort to take a look at the students who have come to our school in the past—where they have come from, what type of schools, what geographic area—and to pull that into our recruiting practices,” he says. “That tends to be where we have success.”

Total institutional aid to students stands at $7,065,000. “We have tried to package need-based aid much quicker during the recruitment cycle so that prospects have a chance to make an informed decision about how we stack up,” Scaccia says. “We’ve also embraced our presence on social media, revamped our information pieces, and done a better job getting them to students.”

The fall 2014 student body included 587 students with 171 entering freshmen. The average institutional grant as a percentage of tuition and fees was 60.4 percent, a discount rate that Scaccia believes is sustainable. “Our institution is somewhat unique,” he says. “We’re smaller than most. For our incoming class, we don’t need to move the needle far to get the classes we need on a year-to-year basis.”

Shrinking as a Strategy

The president of Saint Michael’s College in Colchester, Vt., made national news last year with a bold decision: shrinking as a strategy. “We knew we wanted to get smaller and be better,” says Sarah M. Kelly, vice president for enrollment. “We took a calculated risk. So far, it’s looking like it’s paying off.”

This past year, the discount rate decreased 4 points and net tuition revenue per student climbed 9 percent. Tuition and fees total $51,000, with the institutional grants averaging $15,000.

“We know a large group of people will eliminate a school like Saint Michael’s from their choice set based on sticker price, not taking into account what they might actually be paying,” Kelly says. “Then we have families who know that nobody pays sticker and are very savvy about negotiating. The irony is that the families that least need to negotiate are the keenest negotiators. That’s hard to wrap my head around.”

Despite receiving the most applications in the institution’s history, yield took a hit this year because “we were asking families to pay more, and we were holding very steady on increased quality.” She indicates the SAT scores of incoming students jumped 35 points this year.

During the appeals process, Kelly, who is in her second enrollment cycle with Saint Michael’s, concentrates on making families understand the power of a liberal arts education. “I believe the cycle of financial aid does not end when the financial aid letter goes out,” she says. “I consider appeals as part of the entire process. I personally handled every appeal this year. There were 300.”

She believes an appeal for additional aid demonstrates interest and affinity. “It’s another opportunity to help families understand what they’re getting here versus at another school. I use a lot of data. I might say, ‘Look, the graduation rate at XYZ is 48 percent. Ours is 74 percent. They’re giving you more money, but you might have to budget for an extra year at that school.”

She worries about a trend she is seeing: Well-written, evidence-based appeals from the most well-off parents. Meanwhile, kids from low-income families are drafting their own appeals, which are often less polished. “I’m concerned about the whole idea that appealing for more money is going to become something at which people who are in the best position to do, succeed; and the people who don’t know how to do it, do not. I’m at a Catholic institution. Access, support, and success for those who have the least in this world are an important part of who we are.”

Strategic Advice

Based on what is happening with tuition discounts, revenues, and enrollments, executives offer a variety of strategies to consider in the year ahead:

- Follow an enrollment philosophy. “Instead of concentrating on a set quota, look at the broad range of what you’re trying to do as an institution and for whom you are trying to provide academic programs, and then determine how best you can deliver that,” says Timothy J. Fournier, managing director, Huron Consulting Group, Chicago.

Only after leaders have determined an enrollment philosophy can the institution begin making individual pricing decisions that factor into the discount rate. “The philosophy has to be held jointly by the president, the academic and financial administrative leadership, student life, and student affairs,” he emphasizes. “Every part of the institution should be working together toward that common philosophy.”

Kelly agrees, adding that the discount rates can vary, depending on priorities. “If I’m going into new markets,” she says, “I will have to discount more heavily there. If I’m going for more quality, I might have to pay more. The president, the CFO, the director of admission, the director of financial aid, and I are constantly in conversation.”

- Build a model. At Lycoming College, leaders decide upon the desired class size before considering the tuition discount rate. “We do it a little differently,” Bennett says. “Our board and administrative cabinet will get together and say, ‘We would like to have another class of 400 students.’ We use that number in our financial aid model to determine the level of tuition discounting necessary to reach that goal.”

The model, he explains, considers the number of applications the institution has been getting, as well as the number of actual admits. Students who visit the website or request information are electronically tracked and merged into the model as well.

“We put them into what I call our funnel,” he says. “As the top part of the funnel grows, we get a better picture of the types of students who are interested in us and why. As they come through the funnel, we get more information about their background, their class standings, and different test scores. Based on historical factors of students with similar styles, we can determine the aid amounts or percentage of aid discount that it has taken to get those students to come.”

- Focus on the individual when allocating financial aid. Not all students require the same incentives to enroll, Fournier says. “Don’t ‘over aid’,” he urges. “To a certain extent, all institutions have a formula, and if you meet these characteristics as a prospect, then you get X amount of aid. Many of the students who are applying and being admitted don’t need as much aid as is being offered, which hurts the institution, causing it to miss incremental revenue that can support other academic needs.”

He cites the example of an institution with a strong engineering school considering a prospect interested in engineering and whose parents are alumni and a grandparent is a regular donor. “You know this individual is likely to come to this institution, regardless.” By reducing the aid offer to an amount below the formula, you can still yield that student and use the dollars you save to increase the aid offer to a student who is on the fence and likely to be recruited by your strongest competitors.

“Financial aid needs to be an individual decision,” he says. “Institutions need to use financial aid in a strategic way to match prospects and to determine an individual student’s pricing. We are seeing a lot more of that, but there’s still a long way to go to get to the ideal.”

- Reconsider growth. “More clients are asking whether growth is the right strategy,” Fournier says. “That’s a pretty fundamental shift from what we’ve seen for the last 10 to 15 years. Some institutions are contemplating reducing class size if that will also mean reducing some programs and services around it to reach equilibrium. As the CFO, you can achieve the same net tuition revenue—or even incrementally more—with a smaller class size, if you are more careful about aid and to whom you [give] aid.”

- Stand out from the crowd. “From 1980 to 2010, institutions added academic programs, and auxiliary services and facilities to the extent that they all became the same,” Fournier says. “Now we’re seeing more institutions marketing and actively communicating their points of differentiation.”

For example, he has noticed more faith-based institutions actively promoting their values and the values they bring to their students. “This trend shows that leaders understand the importance of differentiating in the marketplace.”

- Share data. To improve enrollment outcomes, Fournier recommends carefully documenting and sharing with internal admissions staff the information from each contact a prospective student makes. “This is not just for net tuition revenue,” he insists. “This is for the entire enrollment cycle. Everyone in the enrollment process should use customer relationship management (CRM) tools to share information about how they are recruiting and marketing to a prospect.”

Institutions using CRM strategically can make more informed decisions about the appropriate levels of individual aid, as well as reach out to prospects and appeal to their personal interests. For example, a business professor might contact a student on the fence with a message such as, “I understand you’re considering a business major at XYZ. I look forward to having you in one of my classes.”

- Ask for documentation before handing over additional cash. Fournier has noticed an uptick in the phenomenon he calls “the used-car shopping mentality of parents.” Even when you extend a more-than-generous financial aid package, the parent often asks you to up the ante, he says.

“Regardless of the aid offer that is made, parents—and it’s almost always the parents, not the student—will call each of the schools to which their child is admitted and shop for the best deal, saying ‘XYZ University is offering me $1,000 more than you are,’” he says. “I don’t fault the parent for trying to get the best deal, but we, as institutions, have to be more strategic and thoughtful, rather than just capitulating.”

- Stay strategic. “If you’re spending all of your time managing your tuition discount—which is an industry insider term—you are not spending the time you need to be strategic with families and talking about cost and outcomes,” Kelly insists. “Very few people are coming to me and asking, ‘What is your tuition discount rate?’” She urges institutions to concentrate on getting families excited about student outcomes. “If you just talk about the discount rate, you’re missing the boat.”

MARGO VANOVER PORTER, Locust Grove, Va., covers higher education business issues for Business Officer.