A new wave of optimism lifted spirits for college and university endowment managers, while swelling FY13 returns. Financial markets had been quite choppy for most of FY12, due to spending cuts related to federal sequestration, slow economic growth in the United States, and debt crises in several European nations.

The roiling markets calmed in FY13, due largely to the U.S. Federal Reserve’s third round of “quantitative easing,” involving monthly purchases of $85 billion in long-term U.S. Treasuries and mortgage-backed securities. At nearly the same time, the European Central Bank announced renewed efforts to ease the Euro debt crisis by buying Spanish and Italian bonds.

The Central Bank’s actions lowered interest rates on a wide range of consumer products, from car loans to mortgages. That, in turn, helped to increase sales of cars, houses, and other consumer goods, and contributed to moderate increases in jobs in a number of industries.

The Fed’s and European bank’s actions also buoyed stocks in both the United States and abroad. The Standard and Poor’s 500 Index of U.S. Stocks, which increased just 5.5 percent in FY12, rose 20.6 percent between July 1, 2012, and June 30, 2013. International stocks, as measured by the Morgan Stanley Capital International (MSCI) World ex U.S. Index, had an even greater rebound—rising 17.1 percent in FY13 after an abysmal –14.1 percent performance a year earlier. Bonds, which were one of the few bright spots of FY12, had a much tougher time in FY13, with the Barclays Aggregate U.S. Bond Index going from a 7.5 percent gain in 2012 to a –0.7 percent loss in 2013.

The combination of better-than-expected economic conditions and equity gains lifted U.S. higher education endowments and affiliated foundations in FY13. The 835 institutions that participated in the 2013 NACUBO-Commonfund Study of Endowments (NCSE) achieved an average one-year return (net of investment fees) of 11.7 percent in FY13, a sharp correction from the –0.3 percent performance during FY12. And, despite a volatile first quarter for the markets, continued economic growth during the first half of FY14 suggests that the upward momentum in endowment performance may continue.

However, while signs suggest that endowment managers may continue to enjoy some smoother sailing in the short term, some continuing long-term issues—such as sinking student enrollments and declines in government financial support for postsecondary institutions—will continue to challenge higher education leaders. This overview of the results of the 2013 NCSE takes a look back at the investment strategies institutions used to achieve their results, and examines the fiscal and other challenges endowment managers and higher education leaders are facing in FY14 and beyond.

Performance Positives

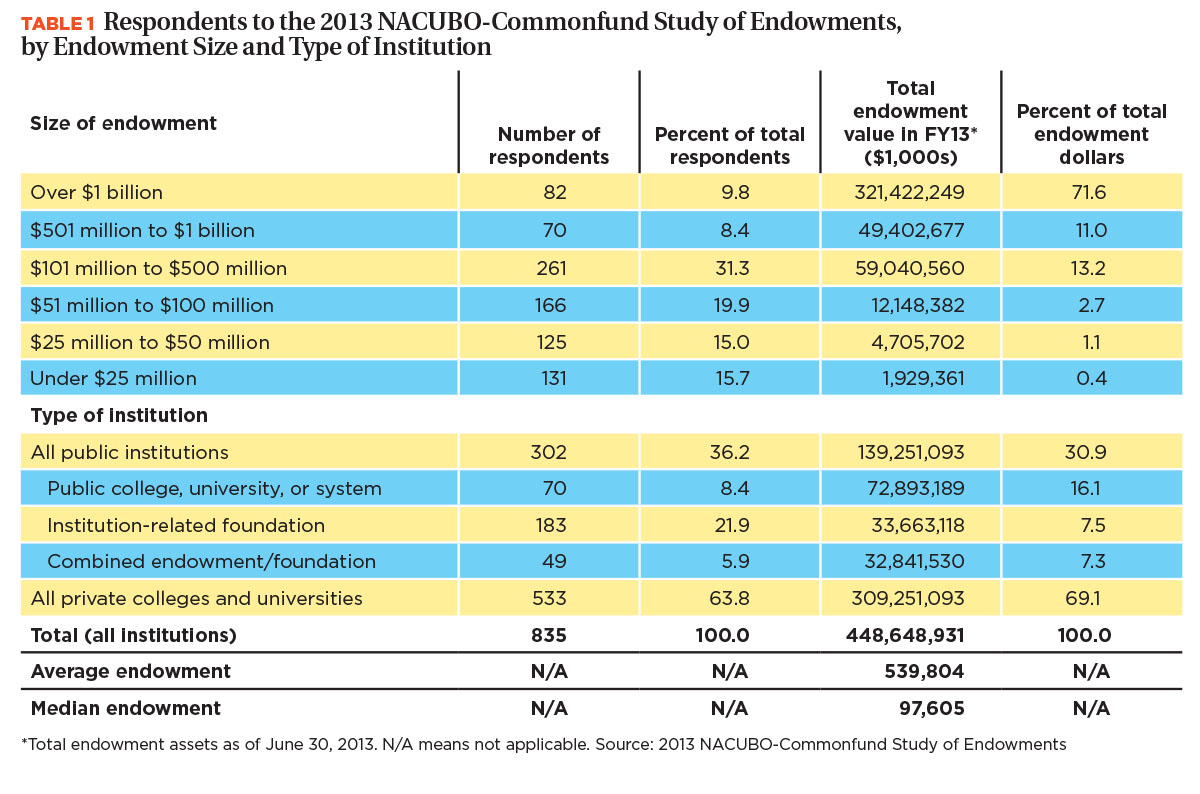

The 835 institutions that participated in the 2013 NCSE held a total of $448.6 billion in endowment assets as of June 30, 2013 (see Table 1). About 10 percent of these participants had endowments of $1 billion or more, while nearly 16 percent reported endowments below $25 million. The average endowment among all participants was $539.8 million, while the median was $97.6 million. Institutions with over $1 billion in endowment assets represented roughly 72 percent of the total endowment dollars of the 2013 NCSE participants.

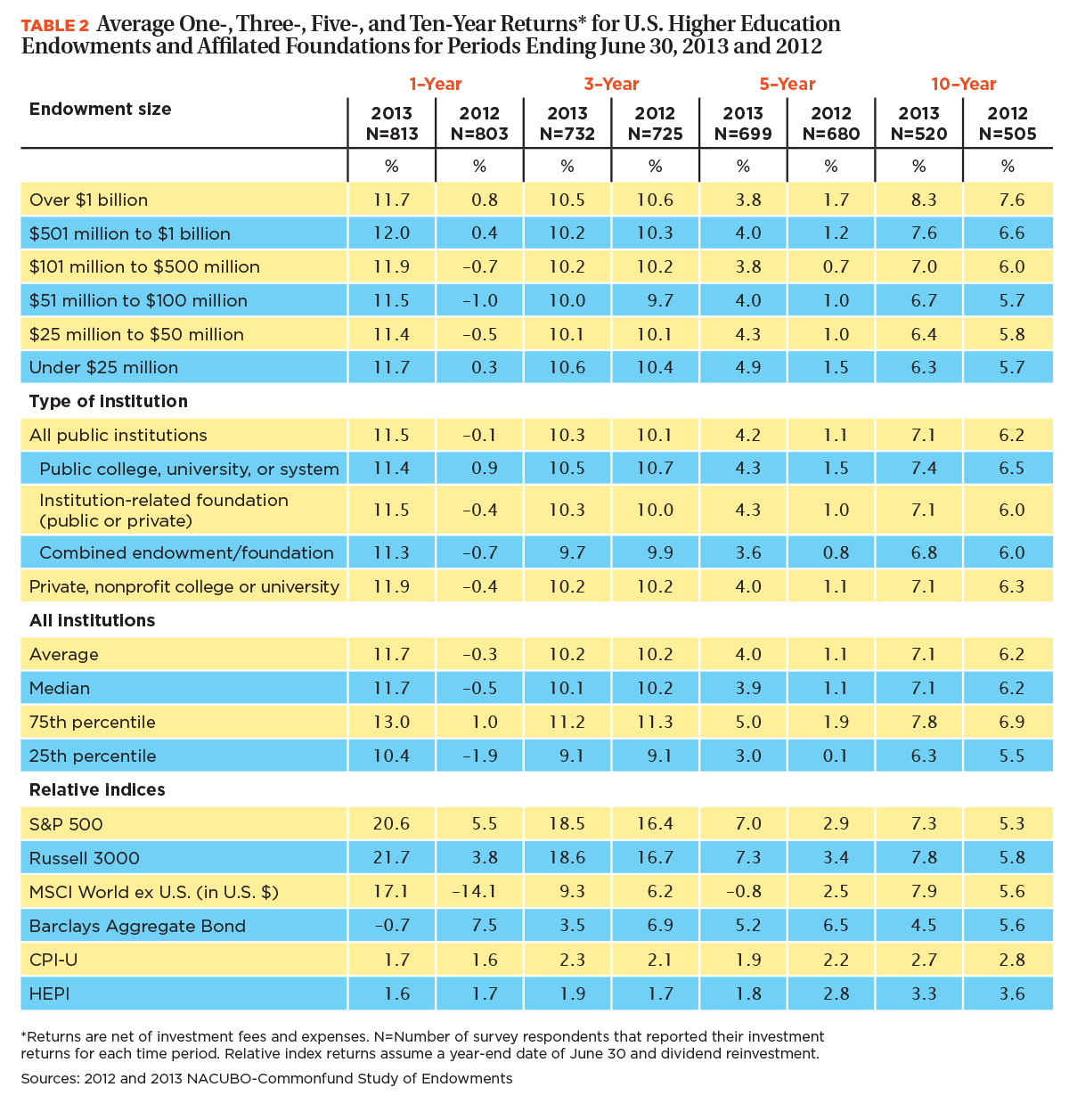

Rising stocks lift all boats. In most years, larger endowments use their size advantage to achieve investment gains that are superior to those of smaller funds. But in FY13, the improved performance of domestic and international stocks benefited endowments of all sizes nearly equally, as Table 2 illustrates. The average one-year return for endowments below $25 million was identical to those of $1 billion or more (11.7 percent). The greatest level of change occurred for endowments between $101 million and $500 million, which reported an average gain of 11.9 percent in FY13 compared with a –0.7 percent average loss the previous year.

Regardless of size, endowments benefited chiefly from their allocations to stocks during FY13. The $12.9 million fund at Spalding University, Louisville, Kentucky, achieved an investment return of 11.6 percent in FY13. Over the past five years, the university has achieved an average annual return of 8 percent, double the overall average for all endowments during the past five years. “We kept to our investment policy that established a 70 percent asset allocation to equities and 30 percent allocation to debt” with no investments in alternatives, says Mark P. Hohmann, chief financial officer.

At the other size extreme, the $885 million University of Colorado (CU) Foundation, Denver, realized a 12.1 percent one-year return in FY13 by “slightly tilting more toward public equities and slightly away from private equity and other alternatives,” says Kelly L. Fox, senior vice chancellor and chief financial officer for the University of Colorado, Boulder. “Some of our commitments in hedge funds and private capital were a drag on our FY13 performance.”

For midsize endowments such as Ball State University Foundation, Muncie, Indiana, keeping to the foundation’s asset allocation approaches even during times of turbulence was the best strategy. The $172 million foundation reported a one-year net return of 13.4 percent in FY13. “We were already overweight in U.S. stocks and had reduced our allocations to 5 percent fixed income prior to the beginning of the year, so we were already prepared for the upturn,” says Thomas Heck, the foundation’s chief investment officer. “We had a great year with U.S. and EAFE [Europe, Australasia, and Far East] equity. Both were a surprise due to last year’s concerns about federal sequestration spending cuts and the crisis in Europe. But we found that the best action for us was to stay the course in spite of the initial uncertainty and volatility.”

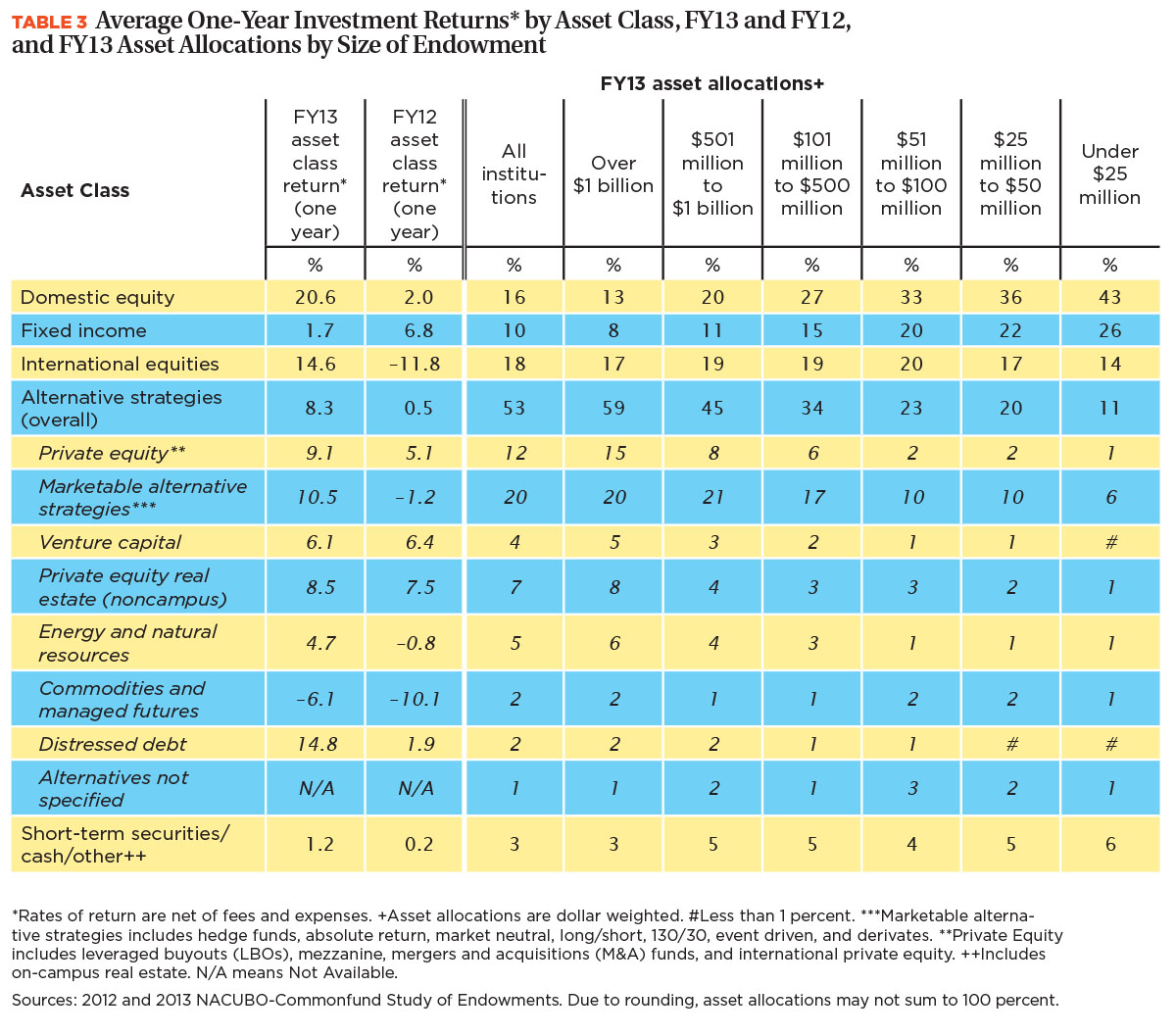

Bonds and alternatives tread water. One reason smaller and midsize endowments had overall returns that were equal to larger funds is that while stocks soared, bonds and alternative strategies such as hedge funds and private equity generally lagged—and smaller endowments tend to have a greater share of their portfolios in equities. On average, U.S. stocks in college and university endowments provided a net return of 20.6 percent in FY13, while overall alternative strategies gained 8.3 percent (see Table 3). Endowments of less than $25 million had about 43 percent of their total funds invested in domestic stocks, compared with just 13 percent for endowments of over $1 billion.

While the performance of marketable alternatives—hedge funds—improved in 2013, overall they still lagged behind the average return for U.S. stocks by roughly 10 percentage points.

Bonds did even worse, rising just 1.7 percent in FY13 after a gain of 6.8 percent the year prior. “Throughout FY14, we saw endowment investors reconsidering the role that core fixed income plays in the overall portfolio,” says Monica Issar, global head of endowments and foundations group, J.P. Morgan Asset Management. “Rising interest rate risk caused investors to rethink whether core fixed income should act as the anchor of the fixed income portion of their portfolios.”

Large and small endowments had various approaches to alternatives in FY13, given their lower return rates. For Spalding University, the avoidance of alternatives has been a key ingredient to their superior returns over the past five years. “Our lack of alternative investments has been a boon for our endowment return the past five years, as that investment style has generally been out of favor.” says Hohmann.

Fox, on the other hand, points out that for larger funds like those of the CU Foundation, some alternative strategies produced impressive gains, even though the overall average was lower than gains in stocks. “We found that hedge funds that focused on particular events, rather than on long or short strategies, performed well,” she says. She also points out an important role hedge funds and other alternatives can play in larger portfolios: added diversification. “Things change from market to market. With hedging strategies, overall volatility can appear lower over time.”

Ball State University Foundation’s leadership also believes alternative strategies can provide additional value in the future. “About 10 years ago, we moved our investments in alternatives from basically nothing to about 50 percent of the portfolio.” Heck says. “We believe there are still a lot of attractive opportunities, especially in private equity, that will produce positive results in the future.”

Will Buoyancy Abate?

The wave of optimism that began in FY13 has continued to rise in 2014, as the economy showed continued signs of stronger growth. In the U.S., during the July 1 to Dec. 31, 2013, time period, economic growth continued to accelerate. The growth rate in the U.S. gross domestic product improved from just 0.1 percent in the fourth quarter of 2012, to 2.5 percent in the second quarter of 2013—and then on to 4.1 percent in the third quarter, and 3.2 percent in the fourth quarter of 2013.

During that same time, the unemployment rate dropped from 7.8 percent to 6.6 percent. Improving economic conditions drove U.S. stock prices, as the S&P 500 index jumped 14.8 percent during the first six months of FY14.

For many endowments, the continued rise in equity prices has led to even higher investment returns. Spalding University reported a net investment return of 13.5 percent for the quarter ending Sept. 30, 2013. “Spalding beat its 70/30 equity/debt benchmark rate by nearly 200 basis points for the first quarter of FY14” due to the rising stock prices, Hohmann reports.

Coming caveats. At the same time, some investment strategies are based on signs that the markets may be in for rougher waters in the coming months. In January 2014, the S&P 500 Index declined 3.6 percent, its worst monthly showing since May 2012. The biggest concerns among investors have been the slowing economy in China, and turmoil in several emerging markets. In addition, it has become clear that economic growth in Europe would remain anemic for a while longer, and some believe the continent may return to recession.

Perhaps most importantly, it is unclear how the markets will react to the Fed’s decision to “taper” its monthly purchases of bonds, from $85 billion per month in December 2013 to $75 billion in January 2014, and then again to $65 billion in February. Reductions in the Fed’s monthly bond purchases may lead to increases in interest rates, which tend to drive down the value of longer-term bond holdings. “The Federal Reserve’s action will be closely monitored by investors in FY14 and will certainly be at the forefront of political and economic factors that play into investment performance,” J.P. Morgan’s Issar says.

Staying the course. Despite the potential for an unsettled investment climate, many endowment managers are sticking with their long-established investment strategies, believing that their current investment plans are the best way to meet their institution’s goals. As Spalding’s Hohmann points out, for most institutions any changes in bonds and other asset classes will be based on these longer-term goals, not short-term stresses in the financial or political arenas. “Our strategy that was established by the board of trustees is a long-term plan, and there has been little to no deviation over the short or middle term,” says Hohmann. “Our investment manager has consistently stayed with a strategy of shorter-duration bonds, given the interest rate and volatile political atmosphere in Washington, D.C.”

UC’s Fox agrees with this sentiment: “Our portfolio’s fixed-income exposure is minimal, averaging under 6 percent. Although that exposure has decreased in the past 12 months, the reason was not based on politics. This decrease can be attributed to our long-term goal of meeting our target of net 5.5 percent real net return, and the expectations that interest rates would begin slowly moving higher.”

Risks and returns. But that focus on long-term goals does not mean endowment managers should not pay attention to the risks that may be present in the current market environment. Leaders at the Ball State University Foundation, for example, have wrestled with creating new ways of measuring the risk they are taking with their investments and how that risk can be balanced against potential longer-term gains.

“We are thinking a lot about risk management,” says Heck. “We are trying to come up with new ways to answer some key questions: How do we calibrate the amount of risk we should take on, given the market environment? How do we integrate investment risk management with an overall framework of enterprise risk management? The amount of risk we take and in what forms is a key part of our board’s current discussions.”

Issar suggests that the answers to these questions will vary widely from campus to campus. “There is no one-size-fits-all with endowments and institutional investors,” she says. “We believe endowments and foundations will be considering changes to asset allocation in FY14, with a focus on loosening constraints in the quest for returns, while at the same time preparing for the long grind that will come with rising interest rates. In the long run, we believe investors will be compensated for their risks.”

Dangerous Waters Ahead?

In addition to the prospect of somewhat murkier financial markets, colleges and universities face other pressures. A recent report from Moody’s Investor Services shows that public and private higher education campuses are also dealing with slower tuition and fee revenue growth, greater needs for financial aid and other support for students, and declining support from state appropriations and other revenue sources.

One of the biggest challenges facing institutions is declining enrollments. Comparing spring 2013 to spring 2012, research indicates that the total number of students on college campuses fell 2.3 percent, according to the National Student Clearinghouse. Demographic trends suggest enrollments may continue to fall for at least the next decade.

Yet, institutions are coming up with a variety of new approaches to meet these challenges. At the University of Colorado, which is “coming off a period of enrollment decline,” leaders have been “looking at processes to reduce costs and are looking at partnering with industry in the future,” Fox says. The university also has begun a new recruiting program that includes more personalized outreach from schools and colleges in order to recruit and retain more students.

Spalding University, which has seen a recent enrollment decline of about 3 percent, has also had to reduce expenditures. “We have elected to continue to spend only where necessary and to adjust downward our annual cost-of-living wage increases,” Hohmann says. But the university also has instituted new programs designed to increase academic services to students and raise revenue.

“For the first time in our nearly 200-year history, the university has obtained a certificate of need to operate a comprehensive outpatient rehabilitation facility,” says Hohmann. “We’ve begun to provide services and receive payments from insurance carriers and Medicare for occupational, physical, and speech therapy services. Not only will this diversify the university’s income stream, it will help prepare our graduates to enter the workforce with hands-on experience.”

Heck mentions that Ball State University may face reductions in state support in the future. He believes the foundation’s role going forward should “involve collaborative efforts between the university and the foundation,” he says. “The foundation can provide the entrepreneurial capital for the university to create new immersive learning opportunities and to develop new modes of delivering education for the future. We can help fund these initiatives, but ultimately the university will play the key role in providing educational services to the students of the future.”

The possibility of troubled waters ahead for higher education suggests that endowment managers, chief business officers, and other higher education executives will continue to be challenged as they lead their institutions through FY14 and beyond. As Hohmann says, “We are going to continue to practice policies of spending prudently, growing the endowment, and using capital or contributed funds to finance expansion. While we have to remain lean, we also have to continue to invest in academic programs to sustain our growth for the future.”

KENNETH E. REDD is director of industry research and policy analysis at NACUBO.