![]()

![]()

A decade ago, the University of New England (UNE) consisted of two Maine campuses with considerable deferred maintenance issues, a negligible endowment, and no cash reserves. Our three colleges enrolled approximately 4,000 students, and our tuition mix was 60 percent undergraduate and 40 percent graduate. Our tenuous financial situation—exemplified by the Council of Independent College’s composite financial index of 1.4—was further strained by the changing national demographics that were hitting our aging state particularly hard, and by the inherent challenges facing private institutions in the saturated Northeast market. Tuition-driven but facing stagnant enrollment, we had to use our line of credit to remain viable over the courses of two consecutive summers.

Amidst this reality, newly installed UNE President Danielle N. Ripich and the UNE Board of Trustees announced a 10-year strategic plan called “Vision 2017.” The plan charted a course for UNE to grow its existing offerings in fields like nursing and dental hygiene into a vibrant portfolio of undergraduate and graduate programs in the health professions. As our state aged, we would supply it with the next generation of doctors, nurses, dentists, pharmacists, physical therapists, and other care providers to meet its growing needs.

Vision 2017 was ambitious, calling for the creation of new colleges, new programs, and new facilities as well as the revamping or replacement of UNE’s existing infrastructure. It would require keen financial planning. University leaders had not managed using metrics and data in the past; now, the university’s ability to survive would depend on changing that culture.

Ten years later, the University of New England is a vibrant, financially healthy university with two state-of-the-art campuses in Maine; a revolutionary study-abroad campus in Tangier, Morocco; and a national reputation for excellence in the health sciences. We have expanded from three to six colleges. Our tuition mix is 57 percent graduate and 43 percent undergraduate. And today, our unduplicated headcount has more than doubled to 10,371 students. Our composite financial index is 5.0. We no longer use our line of credit and, in fact, have built cash reserves.

Online Niches

Central to UNE’s metamorphosis has been the rapid development and expansion of our online programming, facilitated by our business office at every turn, working in tandem with other university stakeholders. Last year alone, UNE enrolled more than 5,400 online students, hailing from all 50 U.S. states and 27 countries. These nontraditional learners engage in programs reflecting UNE’s core strengths in the health-care fields. As students engage in their careers and fieldwork, while simultaneously pursuing degrees, they help build UNE’s brand around the globe. Just how impactful has the expansion of our online programming been? Net income after direct expenses from these programs was $140,000 in 2009; by 2015, it had grown to $9.7 million.

It is not by accident that prospective students have proved so eager to enroll in our online offerings. The success of our online programs has been the result of careful planning and execution, creative problem solving, and a willingness to change course in midstream when conditions on the ground have deemed such shifts necessary.

When we realized undergraduate demographics were shrinking and would continue shrinking for the foreseeable future, we made the decision to focus on expanding our presence in select online graduate markets. Our offerings would be mission-focused, niche programs in areas where our existing expertise would allow us to deliver exceptional quality.

With the help of a third-party online service partner, we launched the nation’s first online Master of Social Work program in 2008. We anticipated 350 enrollees in the first year; after five months, we had accepted 700 students and our waiting list for the program had risen to 650 students. Realizing that we needed to slow down and hire more staff to support registration, financial aid, and student account services, we did just that. After 15 months, we had enrolled more than 1,000 students.

Our subsequent online programs have been met by similar demonstrations of student enthusiasm. Each program fits beneath the umbrella of our central mission to educate health professionals. But more than that, each is the result of a comprehensive marketing assessment that provides an overview of the current market, the growth potential of the market, and the current competitors in that market. This process helps us determine the level of interest in the market for the type of online degrees that we offer.

As data from the marketing study is compiled, we begin developing the elements of our university feasibility study and form a working group of internal and external stakeholders to further assess the program’s potential. This working group typically includes faculty in the degree content area and outside individuals from the industry. The group makes recommendations on program goals and objectives, potential learning outcomes, and curriculum content areas. Eventually, if a program passes muster, it is created and launched.

Swift Changes in Course

In part because our programs so regularly exceeded our enrollment expectations, we confronted fairly early on the internal challenge of managing them all from an operations standpoint. It became clear that we needed a centralized management system that could streamline admissions, instructional design, online marketing, program administration, and faculty recruitment, so we migrated all of our online programs from their respective colleges into a new College of Graduate and Professional Studies.

One of the most important lessons we learned was in the area of leadership. We came to realize that online education had very different administrative needs and student expectations than those to which we were accustomed. Consequently, we created a college steering committee that consists of the university president, provost, chief business officer, and college dean, and began meeting monthly to ensure the college would be as nimble and adaptable as possible. This model allowed us to speak in one voice to our direct reports, implement decisions faster, and fast-track paper work. We could debate issues in one meeting and then implement our decisions. For the sometimes plodding world of higher education, we were moving at the speed of light.

One outcome of these regular meetings was the decision to shift from a traditional model of enrollment to a rolling one. We found that instead of starting all students in a given program or class at the beginning of a 15-week semester, and then waiting until the next semester or year to launch a new class, we could launch new classes as frequently as every two weeks to keep up with student demand. We also worked collectively to extend our online admission staff’s hands-on approach to recruitment to the entire duration of our online students’ experience with UNE, investing in the tutors and other support specialists that have helped us maintain a 94 percent to 97 percent online retention rate.

The CBO’s Role in Resetting Strategy

The chief business officer’s primary role in this institutional transformation was in developing a new culture of data-driven decision making to support the strategic plan. Because we knew we had to accomplish our online expansion without making budget cuts to existing programs or incurring additional debt, it was essential that we develop financially self-sustaining programs.

We implemented the basic concepts of performance-based budgeting, using a model focused on mission, goals, and objectives. The model explains why money is being spent and provides a mechanism to allocate resources to achieve specific results. It clearly shows the logical tie between planning and budgeting.

As we became more familiar with this new way of doing business at UNE, we developed an ongoing systematic method to collect, analyze, and report data that tracks the resources used by each program, work produced, and whether specific outcomes were achieved. We were careful to select the right data points, making sure that the data presented measurable results and was not transactional in nature. Throughout our learning process, we constantly evaluated and adjusted our financial models and benchmarks.

Our benchmark data included:

- Internal benchmarks (year over year).

- External benchmarks (peer groups).

- Operational benchmarks (annual and periodic measurements).

- Strategic benchmarks (long-term operational goal).

What Direction Now?

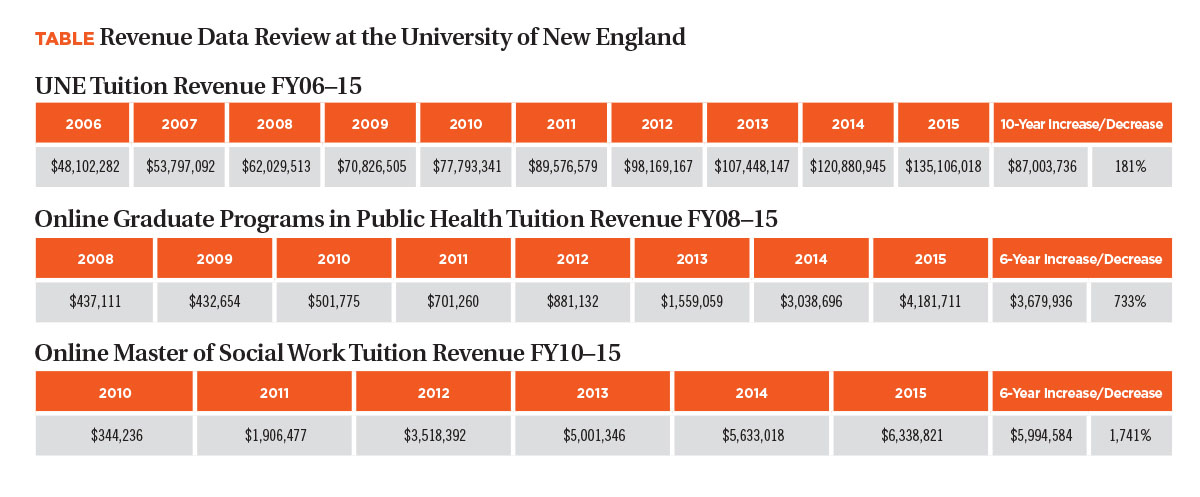

As UNE approaches the end of the 10-year strategic plan that guided us to such a remarkable period of transformation, our internal projections continue to suggest our campus-based enrollment growth will be modest. But our online programs are thriving. At a time when many institutions of higher education are scrambling to develop and build reputations around their online programming, our collective online programs are already one of our hallmarks (see Table for tuition growth summaries).

We are looking ahead, applying the same innovative mindset and analytical principles that guided our initial foray into online education to those areas where we see new opportunities arising. For example, we are expanding into competency-based education, creating partnerships with local and regional businesses so that we can deliver essential professional development programming to their employees.

Overall, the most important lesson to be learned from our story may be the value of a university, president, and chief business officer remaining flexible in their thinking and being willing to persist amidst the ambiguity inherent to any large expansion plan. Our president is an admirer of the great American poet Walt Whitman, and draws inspiration from his advice: “To steer for the deep waters only … . To act boldly and take up the issues and causes worth fighting for.” We have righted our ship, and intend to sail to some amazing waters.

NICOLE TRUFANT is vice president of finance and administration, University of New England, Maine.

SMALL INSTITUTIONS: