Call it whatever you want—big data, analytics, or business intelligence. Institutions are using metrics to make data-based decisions about operations and, yes, even about academics.

Call it whatever you want—big data, analytics, or business intelligence. Institutions are using metrics to make data-based decisions about operations and, yes, even about academics.

“Big data is not a very precise term,” admits Henry DeVries, management consultant, Ellucian, Fairfax, Virginia. He loosely defines the expression as “a big stew” that allows you to pull lots of data points together to find trends and patterns you couldn’t spot by examining spreadsheets, numbers, or names.

“Business officers have historically looked at quantitative analysis and business performance,” he says. “That’s nothing new, but the current environment around big data involves a much broader activity than just looking at what’s happening in the operational side of the institutions. Now the academic side is paying attention to analytics and how it can help with student success. This is a relatively new approach.”

To discover how institutions are using big data, Business Officer recently interviewed a handful of academics, administrators, suppliers, and technology experts from institutions large and small.

Analytics Predict Retention Risks

Through an initiative launched in the spring of 2013, Chandler-Gilbert Community College in Chandler, Arizona, is using predictive analytics to boost its student retention rates and optimize spending on its retention activities.

“Like all community colleges, we want to boost our graduation rates,” says Bradley Kendrex, associate dean of finance and business services. “As we started to pick that apart in a somewhat pragmatic way, we realized it all gets back to retention. In community colleges, our students tend to be gone before we see a lot of evidence that there’s trouble.”

He points out that unlike four-year universities, community colleges don’t have much information about their new students—such as SAT scores or high school GPAs—because their classes tend to be open entry and attract a broad range of people, some who are just out of high school and others who haven’t taken a test in 40 years.

“By traditional definitions, we don’t know who we’re getting, so we have to wait and see how they’re doing in classes and rely on feedback from faculty members to intervene to keep those students on track,” he says. “As we started talking about that problem, we started thinking, ‘How could we know earlier in the process when we have a risk issue?’”

So Kendrex and Theresa Wong, director of research, planning, and development, began testing an analytical model that churns through hundreds of data points to predict student behavior. The data points consider whether students are in a developmental English or math class, how far they live from college, what time of day they take classes, how heavy their course load is, when they register for classes, whether they take student success classes that teach study skills, and a variety of other seemingly unrelated factors.

“We took all this basic registration stuff, crunched through those numbers, and built a model that has proven to fairly accurately predict those who are not likely to stick around,” he says. “Based on that data, we can target outreach for those particular students.”

He is quick to emphasize that this statistical cocktail does not reveal why students are dropping out—only who is a likely candidate to do so. “It is expanding the horizons of how we think about data on campus,” he says. “The key, beyond getting the math and statistics to work, is converting the data into something actionable.”

Students Get Signals

Gerry McCartney, system chief information officer and vice president for information technology, reports that Purdue University. West Lafayette, Indiana, has relied on an analytics tool for in-course student guidance for the past five years. “Using big data and analytics, our Purdue-developed software can tell students as early as the second week of the class if they are in danger of failing,” he says.

This program, called Signals, looks at students’ online academic behaviors, such as whether they opened a reading assignment or completed a set of math exercises, and combines this information with 20 data points, including standardized test scores, high school GPA, and current grades.

“We use Signals in big introductory classes where there are many hundreds of students,” he explains. “Signals warns students that they are on a trajectory they don’t want to be on. The software isn’t solving the problem. It is merely saying, ‘Based on your behavior and background, what you’re doing right now isn’t going to get you where you need to go.’”

According to a recent review of data from the 2007 cohort of students, the software has increased six-year graduation rates by 21.48 percent. The increased graduation rates were for students who were in two or more Signals-enabled classes, compared to students who had not taken any Signals-enabled courses.

McCartney believes the software is particularly helpful to students who didn’t go to competitive high schools. “They didn’t have to perform at a particularly high level to get an A,” he says. “When they come into a competitive environment like Purdue, they sit in large classrooms surrounded by students who look like those from their high schools, and they might not get their first grade until week five or seven. Then they don’t know what to do when they get into academic trouble.”

In addition to a visual warning, students receive messages prepared by instructors that might suggest talking to a graduate teaching assistant or visiting a writing lab, he says. “There’s nothing magical about the intervention, but it’s timely. It catches them early.”

He adds that Purdue’s data mining and analysis software has been released as a commercial product by Ellucian called Course Signals.

It’s All About Student Completion

As of July 1, none of Ohio’s state funding comes from enrollment, reports Jennifer Spielvogel, vice president, evidence and inquiry, Cuyahoga Community College, Cleveland. “It all comes from performance-based metrics. All of a sudden, it’s not about how many students we get in the door, but how many are progressing. The state is certainly looking at big data—and so are we.” (Read more about performance-based funding in “Funding Outcomes”.)

For this institution—and others that are facing performance-based metrics—“it’s all about student completion,” Spielvogel says. “We look for any kind of insight we can gain from the data about who is progressing, who is not progressing, and anything we can take action on.”

She gives the example of a cluster of students who have completed their required 60 credit hours for graduation but haven’t yet finished their college-level math. “At the big data level, I can tell the campuses how many students fall into these categories so we can do something about it.”

Spielvogel, who reports to the provost, supervises five analysts. Together, they sift through data on almost 50,000 unique students each year.

The new state formula budgeting model awards access points to three categories: Pell-eligible students, 25-and-older enrollees, and underrepresented minorities. While she readily admits she can’t influence the first categories, she thinks she might be able to increase the third by scouring the data to ensure that a student’s underrepresented status is properly reported. “Could that be a blank field for some of our students?” she asks. “We don’t want to miss out on access points and extra dollars because the information isn’t in our system.”

Typically, Cuyahoga would get about 15 percent of available funds in the state funding pot for community colleges. However, by breaking down state funds by progression points and milestones, she knows that her college is only receiving about 9 percent in the category of certificates and degrees. “The question is why,” she wonders. “Is it because we have programs that have 29 or 28 credit hours and what the state is rewarding is a 30-hour certificate?”

To correct this perceived funding gap, Spielvogel is exploring how the college could modify certificate programs, making them more valuable as defined by the state. For example, could students who are striving for a particular degree earn a certificate somewhere along the way?

“Maybe we just haven’t defined it as a certificate, and maybe other community colleges in the state have,” she says. “If you look at the auto mechanics associate degree, it has content areas that could be a 30-credit-hour certificate—and may be all the student needs to get a job.”

She believes that in the past few years, community colleges have been asked to reimagine the student experience. “Our policies and procedures until now have probably focused on getting students in the door,” she says. “Our processes internally now have to focus on getting them out.”

Customize Fundraising Appeals

Miami University of Ohio, Oxford, recently closed a nine-year comprehensive fundraising campaign with a goal of $500 million. “We came in at $536 million,” reports Tom Herbert, vice president for university advancement and executive director of the Miami University Foundation.

He attributes much of the success to fundraising analytics, which he believes has become more sophisticated in the past five years. “The depth of information—and the accuracy—is there for institutions to mine,” he says. “Our alumni database is our version of big data. When you’re working with an alumni body of 200,000 people, anytime you can segment that population so your mailings can more effectively appeal, that’s a plus. If we can determine that this slice of the alumni database is more attractive to this kind of appeal, both in terms of mailings and phone calls, we’ll use that to get our fund numbers up.”

For example, suppose he has identified a set of graduates who worked on the student newspaper during the ’70s. “Using that as an appeal, we can customize our mailing to reflect the time they were on campus, saying ‘Would you please consider making a gift back to Miami that would help support that activity?’ The people receiving the letter understand that we’re being much more personal to their experience, which is flattering, as opposed to receiving a blanket appeal.”

His staff, which includes 114 FTEs from marketing, IT, fundraising, events, and alumni affairs, gathers data from a variety of sources. “We have our own data-input people who scour different databases,” he explains. “Every so often we will have an external data vendor come in and refresh what we have in our own database to be sure that our data is as accurate as possible.”

In addition to collecting the obvious—valid mailing and e-mail addresses and phone numbers—the institution can slice and dice the data by graduation date, campus activities, and other criteria, including economic status. For example, during a wealth screening, outside vendors go through the university’s database of alums and try to determine from public records of real estate and stock holdings where alums land philanthropically. According to Herbert, based on public records, a graduate might be rated $5,000 to $25,000 in terms of their potential gifts.

He explains that fundraisers are assigned specific territories of the country to cultivate for potential donors. “Using analytics, we can target the people in the Bay Area, who we think have the greatest potential and inclination to help us,” he says. “That gives the fundraiser in that area an idea of the people to try and see.”

Why Waste Energy?

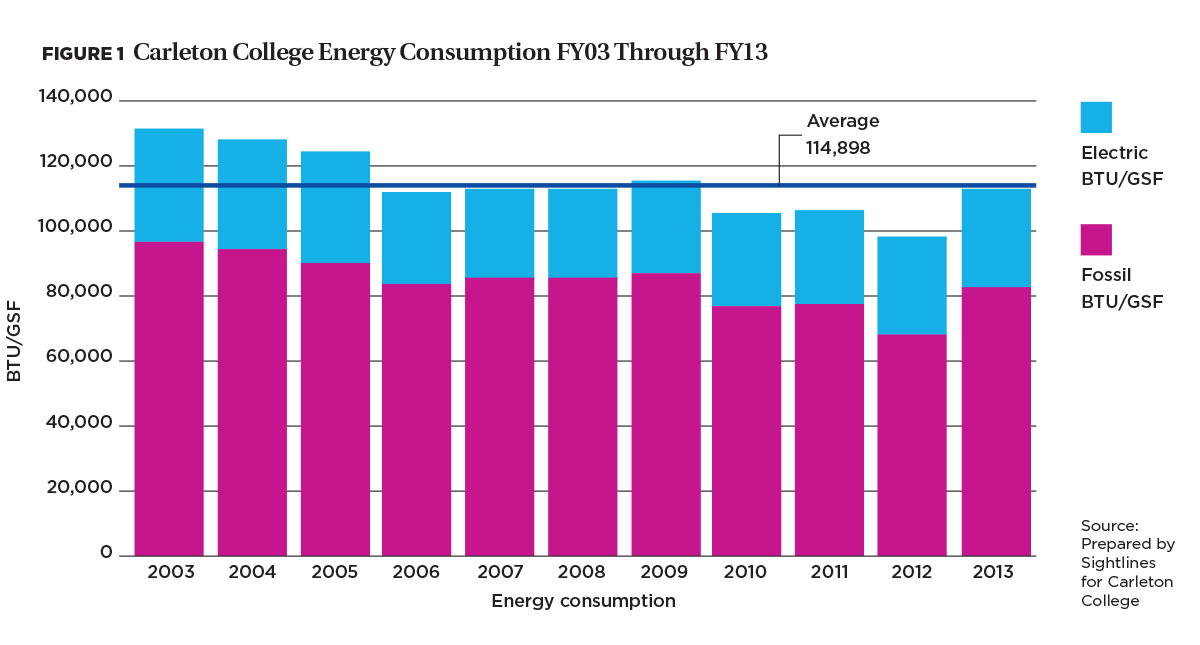

For years, Carleton College in Northfield, Minnesota, has operated a campuswide building automation system for facilities that turns air conditioning systems on and off and manages room temperatures. The historic directive was simple: If people didn’t complain, everything was fine—no adjustments necessary.

“The original point of that system was really to maximize comfort and convenience for everyone using the space and to lower the cost of managing it,” says Fred Rogers, vice president and treasurer. “It provided very little cumulative information on system operations or performance. In the last number of years, we have increased the ability to pull that information together, analyze it over time, and focus on it as a method of developing information about our operating efficiency and where we ought to be investing further funds to improve our energy performance and reduce our operating costs. We’ve made much better decisions as we’ve gathered more information about how the campus operates.”

These days, staff members are scrutinizing data surrounding total operating times, cycle times, and costs. “If a system runs all night, it may not make anybody uncomfortable, but it’s expensive,” Rogers observes. “If lights are on all night, no one complains, but they don’t need to be on. We’ve made a number of reductions to make the buildings operate more effectively. Our goal is to continue to reduce the energy consumption per square foot of the campus. Over the last few years, even as we’ve slightly increased total space, we’re reducing total energy consumption of the campus.” (See Figure 1, “Carleton College Energy Consumption FY03 Through FY13.”)

Using a database of more than 450 campuses to help institutions drive improvements in the allocation of operating and capital resources. David Kadamus has noticed a shift to the use of lower-cost natural gas, away from coal and oil, to reduce greenhouse gases, promote sustainability, and save money.

Kadamus, who is the president and CEO of Sightlines in Guilford, Connecticut, recalls one campus that wanted to generate electricity using natural gas to cut costs and to prevent the interruptions common to its area. In this example, the institution planned to put a cogeneration system in as a standalone power supply, independent of the heating and cooling systems. After evaluating comparative campus data that showed that the campus’s heating use was well above peers, the focus shifted to a more coordinated review of the institution’s entire energy profile.

By evaluating daily consumptions that factored in peak loads and base loads, Sightlines showed how a more integrated approach could accomplish the institution’s goal of electrical independence while also lowering its heating and cooling costs.

“By looking at cogeneration as an integral part of the heating and cooling systems, they were able to use the waste heat off the generator to significantly reduce boiler hours and lower their total energy consumption on the heating side. A useful byproduct was that this strategy also extended the useful life of the boilers, which reduces capital costs,” Kadamus says. “By picking the right types of major investment equipment—whether it’s the right-sized boiler or the right-sized generator to make electricity—you reach a more effective, longer-term outcome.”

At another institution, Kadamus helped officials, who were convinced they needed a new academic building, reach a data-driven decision.

“After running the numbers on utilization of academic space, within the context of comparable campuses, we found the classrooms were not well utilized and that, in general, were one and one half to two times the size of the classes. The capacity was 40 to 50, while most class sizes were 18 to 22. The solution was not to build a new building, but instead to take two rooms and make them into three—at a fraction of the cost. By examining the data, the institution could increase the utilization of the buildings dramatically, solve the programmatic issues, and avoid tremendous capital investment.”

Don’t Take This Personally

Regardless of how you define it, big data is transforming the way colleges and universities are being managed—and this trend is just in its infancy. Improving student success, identifying new sources of public support, increasing alumni giving, and reducing energy consumption are but a few of the opportunities waiting to be uncovered by data.

As you proceed, a word of caution: Don’t try using data as a weapon in organizational conflict, Carleton’s Rogers warns. “This should be a collaborative effort where we’re all working to get information because we care about the results,” he says. “We have to create an environment where everyone is open to honest introspection and evaluation. The data might be positive—or not—but it’s not personal. It’s intended to help the institution.”

MARGO VANOVER PORTER, Locust Grove, Virginia, covers higher education business issues of Business Officer.

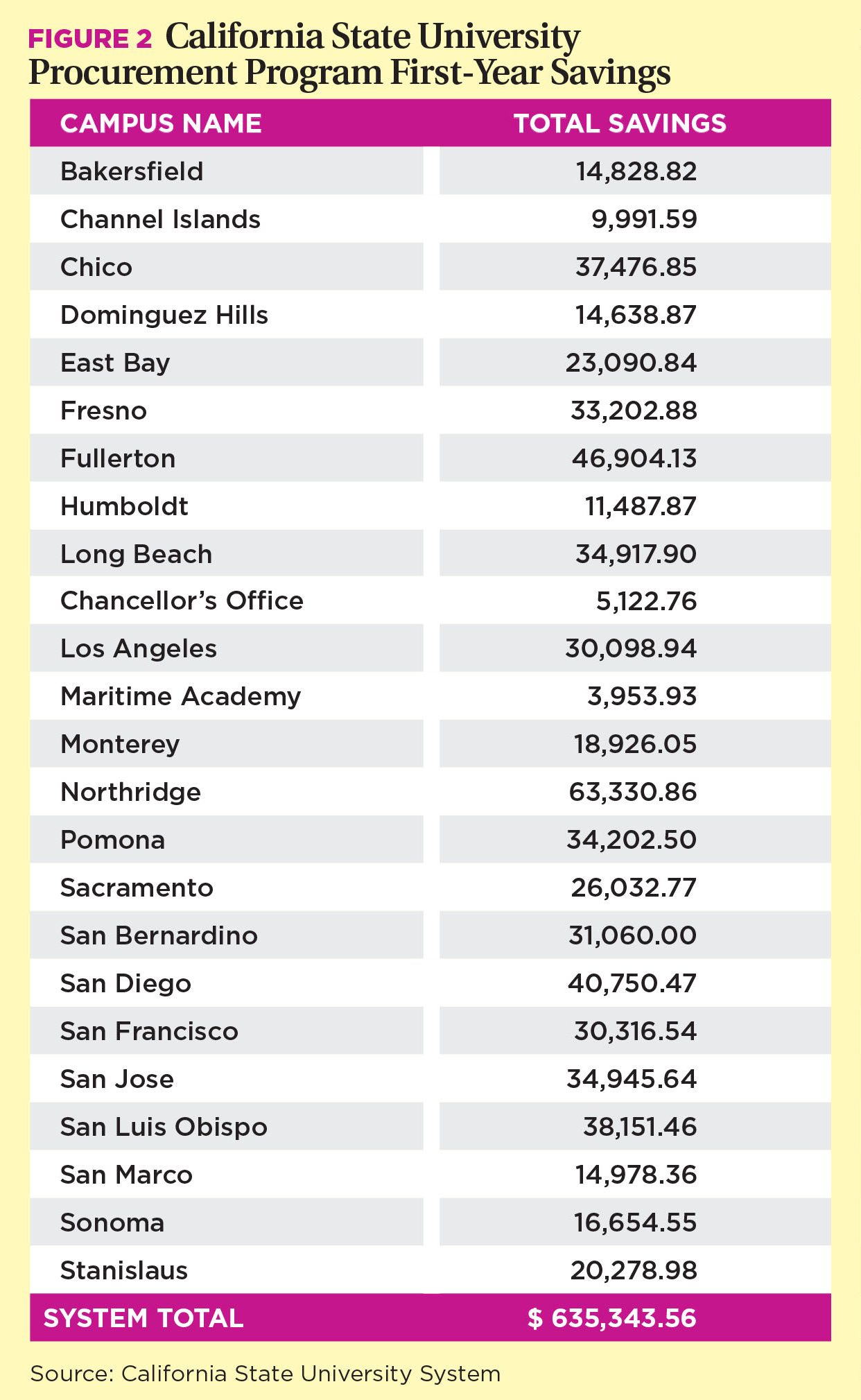

After analyzing annual expenditures of office supplies across the system, officials at California State University discovered they could save a bunch by participating in an automatic-substitution program with OfficeMax, a long-standing partner.

After analyzing annual expenditures of office supplies across the system, officials at California State University discovered they could save a bunch by participating in an automatic-substitution program with OfficeMax, a long-standing partner.