Have we reached a breaking point for tuition discounting?

As the financial fallout from the coronavirus pandemic plays out, this question is on the minds of many chief business officers and other leaders of private nonprofit colleges and universities. Even before the onset of COVID-19, many of these institutions were facing an environment of rising expenses, declining enrollments, and strained growth in revenue. Within this context, leaders of these highly tuition-dependent institutions have felt mounting pressure to increase their use of tuition discounting to meet their enrollment and revenue goals.

At the same time, many campus leaders are seeing the danger signs of continually rising discount rates—these practices are very costly. Nationally, colleges and universities spent more than $52 billion to provide grants and scholarships to undergraduates in 2018–19, according to the College Board. The amount of institutionally funded scholarships and grants awarded to undergraduates attending American postsecondary schools is now greater than the total allocated from college scholarship and grant programs run by federal and state governments combined.

As the results of the 2019 NACUBO Tuition Discounting Study show, even before the onset of COVID-19, many campuses were increasing their discount rates in order to meet their enrollment goals. But the cost of increasingly higher discount rates has been intensifying strain on net revenue, particularly at tuition-dependent baccalaureate schools. The added pressure of COVID-19 will undoubtedly make this situation even more precarious for many of these schools.

Discount Rates Continue to Climb

While all types of higher education institutions award scholarships and grants to meet students’ financial needs, rising aid expenditures have been particularly noteworthy at private nonprofit higher education institutions because these schools are more dependent on tuition and fee revenue to fund their operations. For this reason, NACUBO’s annual tuition discounting study focuses exclusively on the discount rates and institutional grant allocations at private nonprofit colleges and universities.

The 2019 TDS is based on results from 366 independent institutions that were members of NACUBO as of September 2019. These participating schools provided their final aid expenditures and other data for academic year 2018–19 (as of fall 2018) and preliminary results for 2019–20 (as of fall 2019, before the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic).

The TDS measures the effect that institutional grant aid expenditures have on college and university finances. One of the key statistics in the report—institutional discount rate—measures total institutional grant dollars awarded by the participating schools as a percentage of the gross tuition and fee revenue they collect from first-time, full-time first-year undergraduates and from all undergraduates. The aid dollars in the study include undergraduate grants, scholarships, and fellowships that are funded by tuition and fee revenue; they also include scholarships and grants that are funded by restricted and unrestricted endowment funds, general investment earnings, donations to the institution’s general scholarship/financial aid fund, and other sources of revenue. Aid dollars to graduate and professional students are not included, and neither is spending on tuition remission and tuition exchange programs.

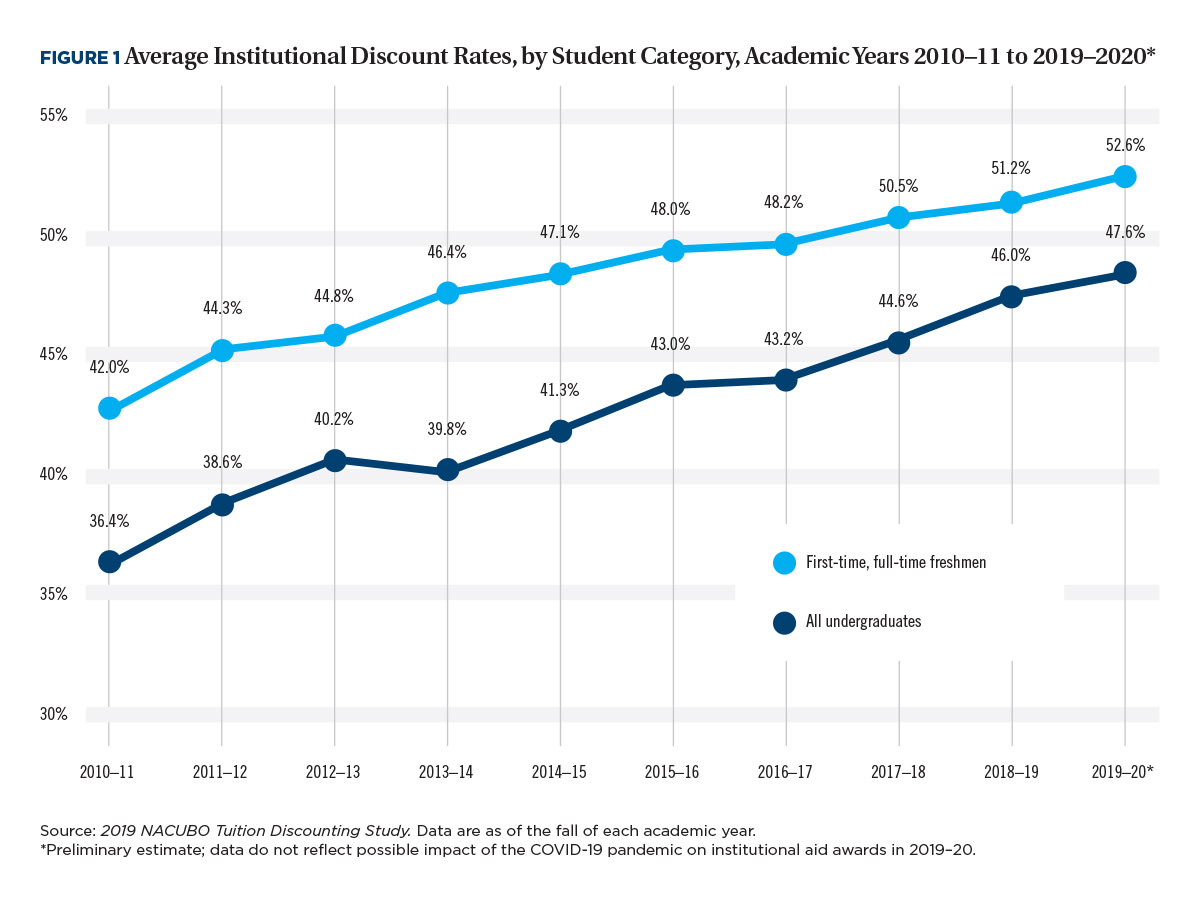

While institutional tuition discount rates reported in the TDS have been rising for much of the past decade, the increase in discounting appears to have accelerated recently. Between academic years 2016–17 and 2018–19, the average institutional tuition discount rate for first-time freshmen grew by 3 percentage points, to a record high of 51.2 percent (see Figure 1). For 2019–20, early projections suggest that the average freshmen rate will continue to rise to 52.6 percent.

The average discount rate for all undergraduates, while lower, is on a similar growth trajectory—rising from 43.2 percent in 2016–17 to 46 percent in 2018–19—and is projected to rise to 47.6 percent in 2019–20. This projected rate suggests that, on average, for each dollar of tuition and fee revenue that private nonprofit colleges charge to all undergraduates, they award nearly 48 cents to institutional grant aid recipients.

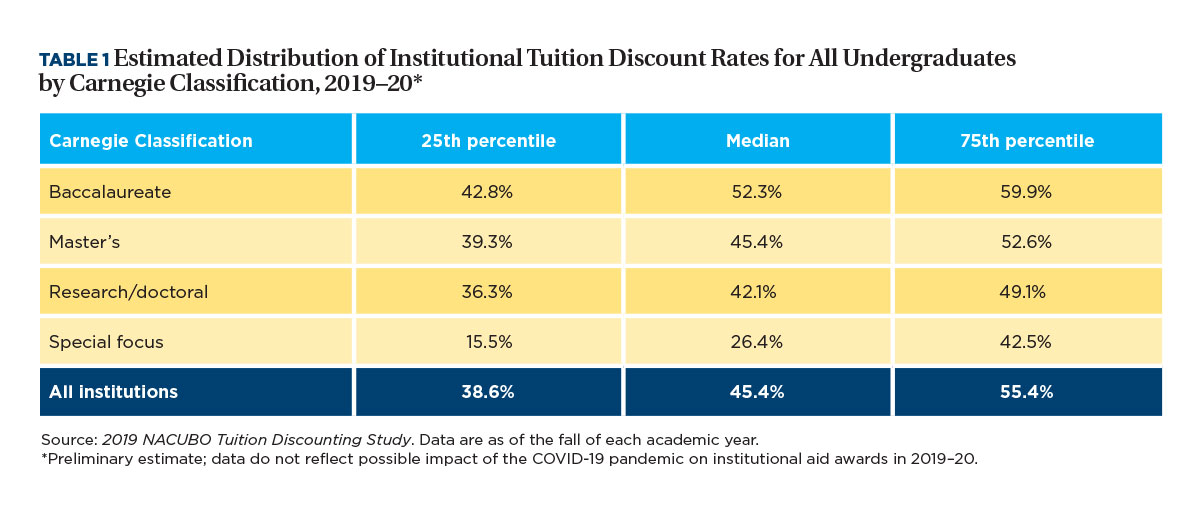

While the overall average discount rate for all undergraduates was 46 percent in 2018–19, some institutions had rates that were considerably higher, while others had rates that were well below the average. About 25 percent of TDS participants that were classified as baccalaureate institutions by the Basic Carnegie Classification system had all-undergraduate discount rates of 59.9 percent or higher, while another 25 percent had rates that were 42.8 percent or lower (see Table 1). Research/doctoral universities, on the other hand, had a lower-quartile average discount rate for all undergraduates of 36.3 percent versus 49.1 percent at the higher-quartile level.

More Students Receiving Higher Awards

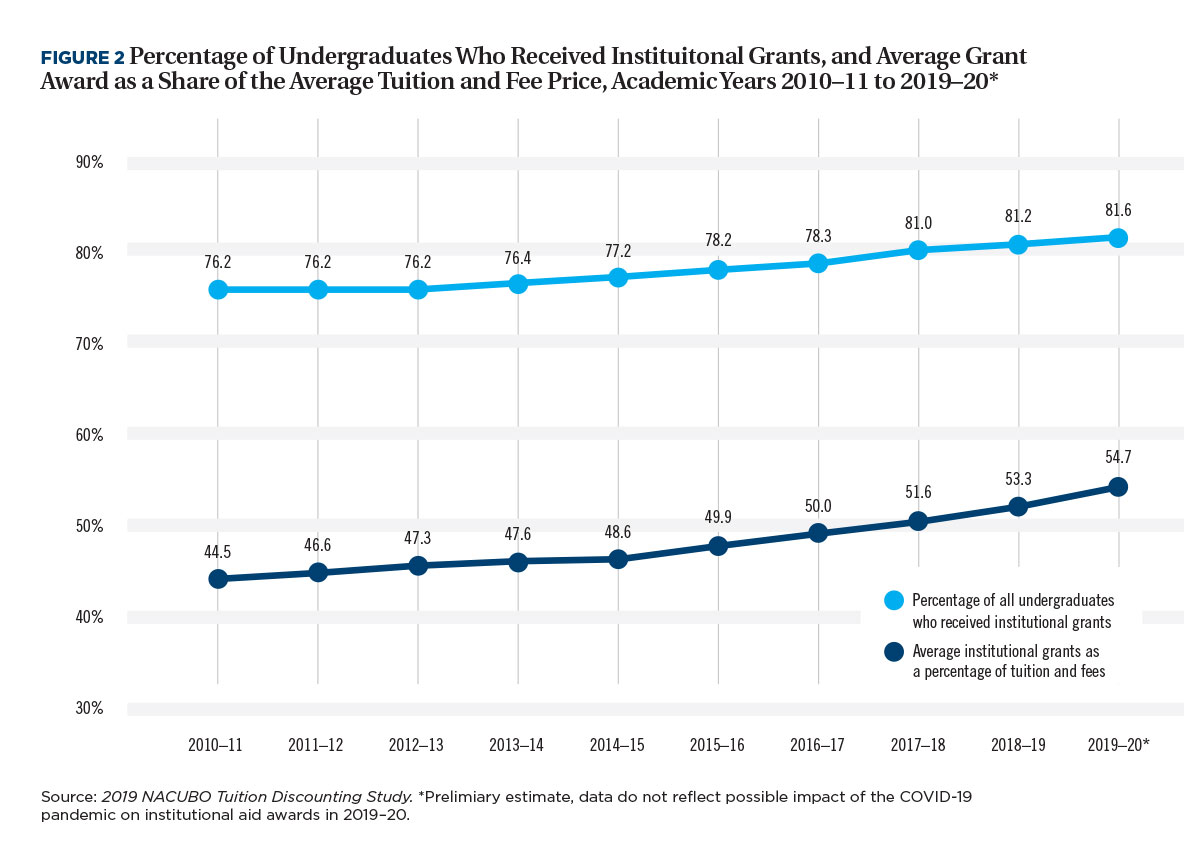

Discount rates have risen in part because a greater share of undergraduates has received institutional grant awards, and the average grant award amounts have covered a larger share of the average tuition price. Over the past decade, the share of undergraduates attending private nonprofit colleges who received institutional grants grew from about 76 percent to nearly 82 percent (see Figure 2). More importantly, the average grant as a share of the tuition and fee “sticker” price jumped from about 45 percent to nearly 55 percent over the same period.

Slower Growth in Revenue

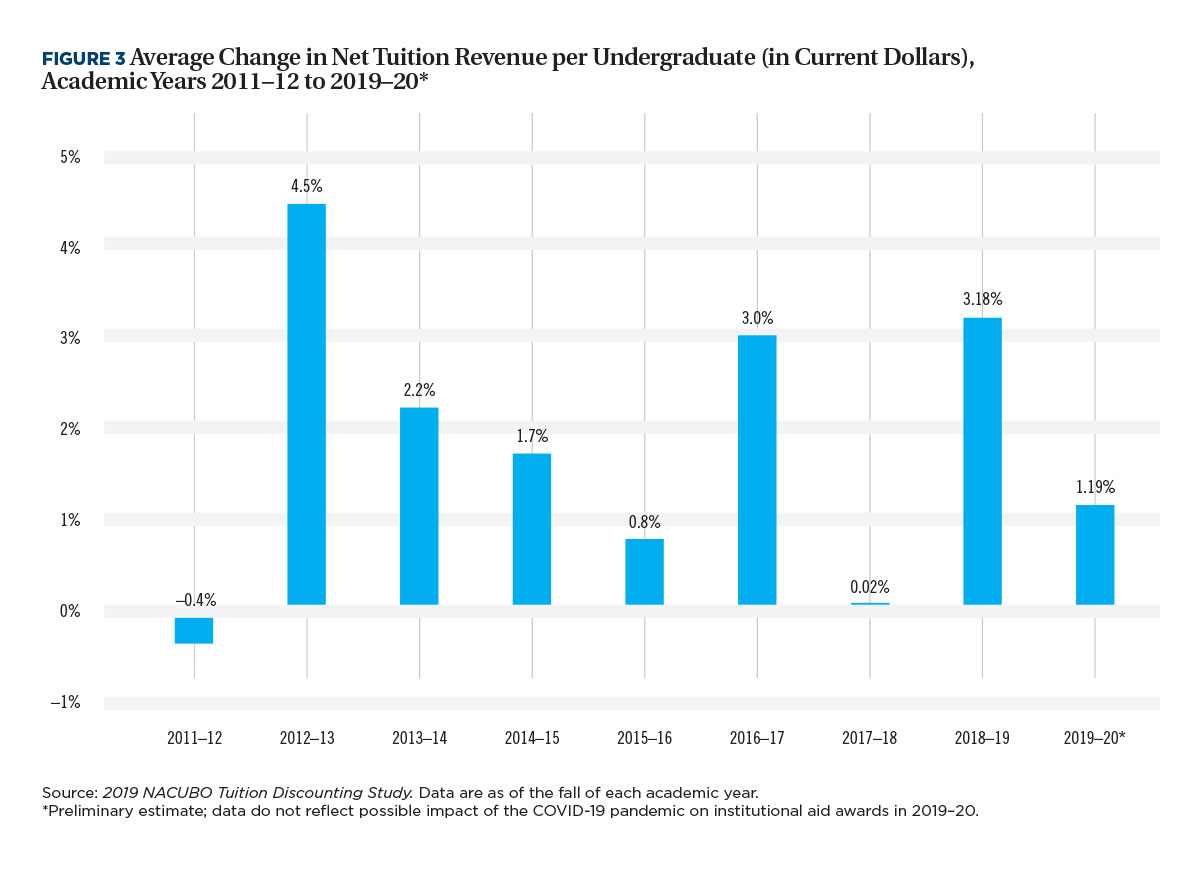

As Figure 3 shows, the recent increases in tuition discount levels combined with the rising share of students getting larger awards has led to a declining rate of growth in net tuition and fee revenue per undergraduate—calculated as gross tuition and fee dollars minus institutional grant aid.

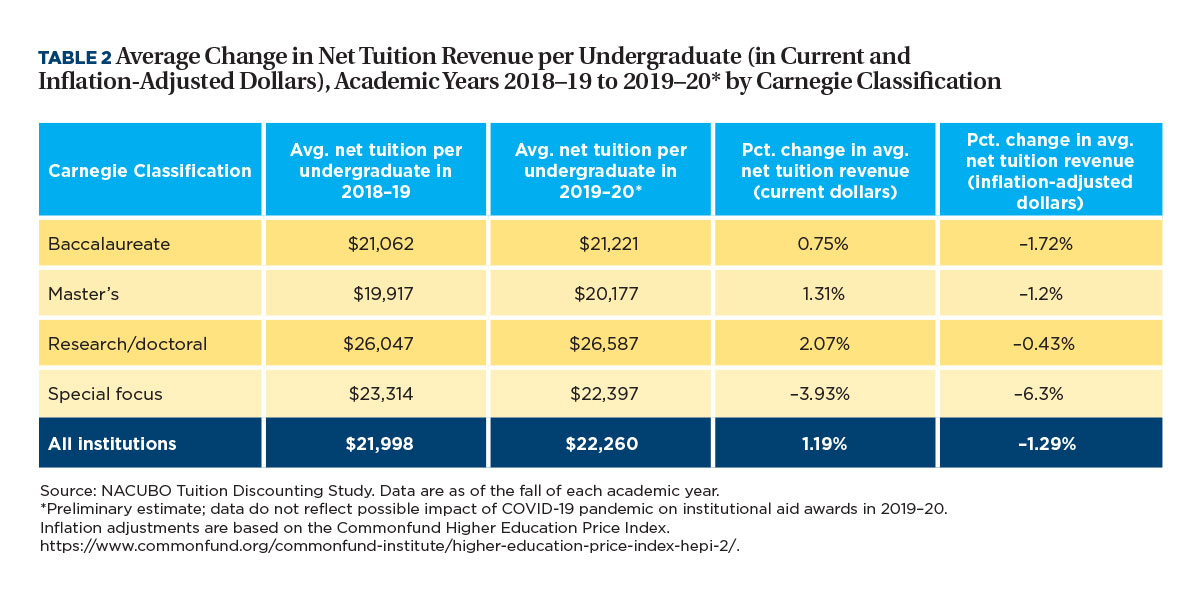

Initial TDS data show that between 2018–19 and 2019–20, net tuition and fee dollars per undergraduate on average grew only 1.19 percent in current dollars (not adjusted for inflation) at private colleges, compared with a growth rate of more than 3 percent in the prior year. Net tuition revenue has been very volatile over the past decade—rising by 4.5 percent in 2012–13 but staying essentially flat in 2017–18.

This lack of growth in net revenue is further exacerbated by inflation, as measured by the Commonfund Higher Education Price Index®, which rose by an estimated 2.5 percent between FY18–19. Thus, the 1.19 percent current dollar change in net revenue equates to a –1.29 percent drop once inflation is taken into account.

Inflation-adjusted losses in projected net revenue are even greater at baccalaureate schools, which saw a –1.72 percent decline in net tuition (see Table 2). Even research/doctoral universities saw a –0.43 percent real dollar loss in net tuition revenue.

Declining Enrollment Despite Increases in Discounting

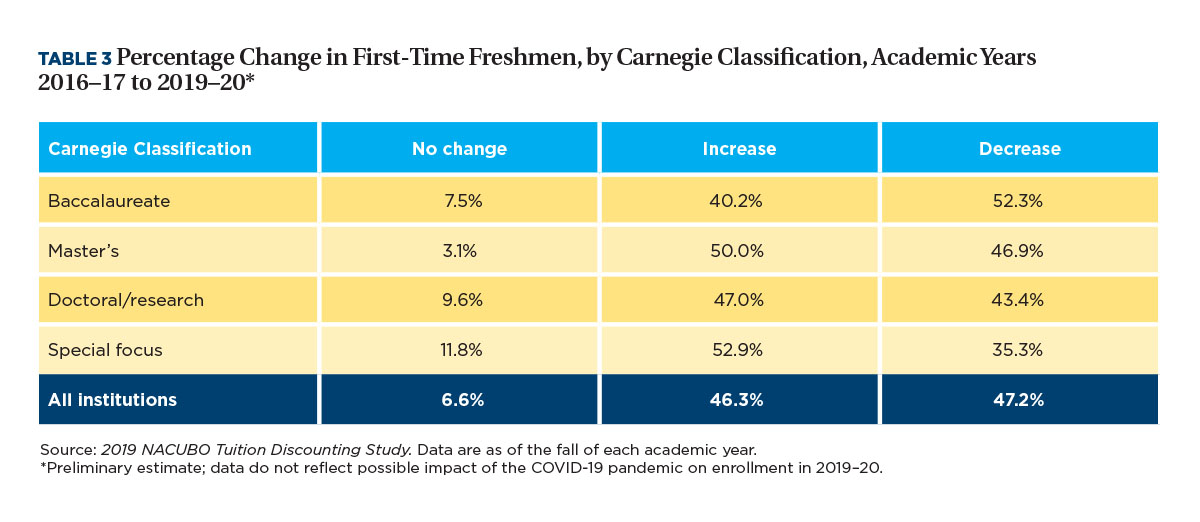

One factor contributing to the low growth in net tuition revenue is that, at many schools, the number of entering first-time first-year undergraduates has declined despite the recent increases in tuition discount rates and institutional grant awards. As Table 3 demonstrates, over the past four academic years, 47.2 percent of TDS participants have seen their enrollment of entering freshmen decline, while only 46.3 percent have seen their freshmen enrollments rise.

Much of the decline in first-time student enrollments came from baccalaureate colleges and universities. More than 52 percent of these schools reported declines in their freshmen enrollments, while 40.2 percent had increases. In contrast, about 47 percent of doctoral/research institutions saw enrollment increases, compared with 43.4 percent that saw declines. About half the master’s institutions also saw increases in first-time freshmen students.

Seeking New Strategies

The continuation of slow growth in net tuition revenue may have a chilling effect on the overall finances of many independent institutions. In 2016–17, four-year private nonprofit colleges derived the plurality of their total funding—approximately 30 percent—from net tuition and fees, according to the National Center for Education Statistics. Master’s and baccalaureate schools obtained even higher shares of their revenue from tuition and fees. Further declines in this revenue source may limit the ability of institutions to fulfill their educational and public service missions.

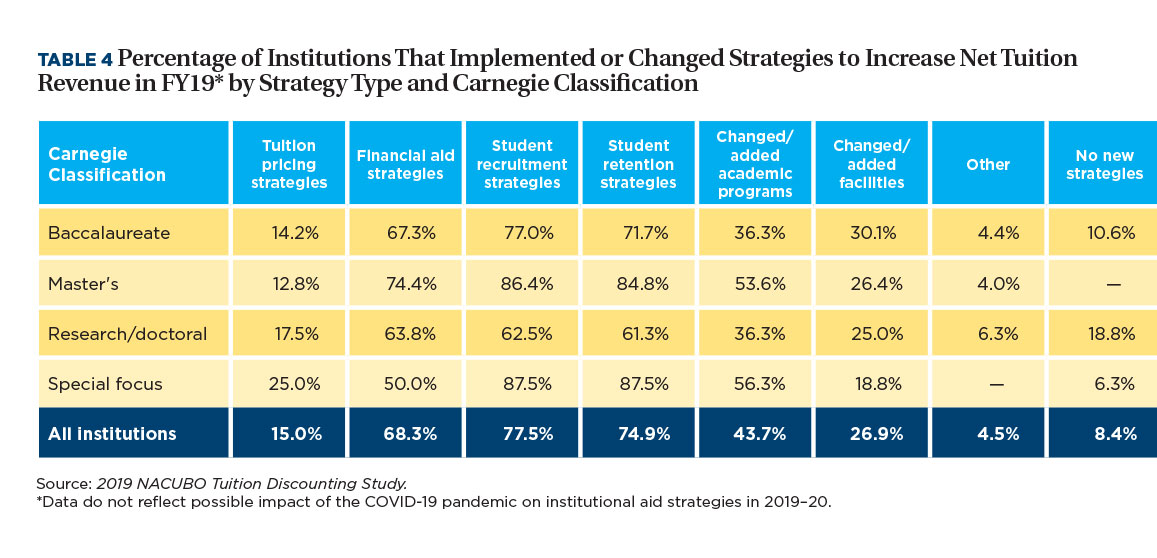

Thus, many campuses are taking a closer look at their current strategies and deciding that these downward trends are no longer financially viable. The TDS asked campuses to identify what other strategies they have implemented or planned to change in FY19 to increase their net revenue. As Table 4 illustrates, student recruitment and retention were the most widely new or changed strategies cited. About three-quarters of survey participants said their colleges changed or planned to use new student recruitment and/or retention strategies, with master’s-level colleges being particularly likely to focus on these strategies. (Since many institutions try a variety of different approaches simultaneously, respondents were allowed to select more than one type of strategy.) Research/doctoral institutions, on the other hand, were the most likely to say they had not used any new strategies.

These findings may suggest that more institutions are trying new approaches to meet their students’ needs in a more financially sustainable way. In the long run, these and other alternatives to tuition discounting may help guide institutions toward greater control of aid spending. But in the short term, institutions will likely face even greater pressure to increase grant awards to students. The COVID-19 pandemic is likely to increase the number of students who will need financial help to attend private nonprofit colleges and universities of all types. The demand for additional aid may be particularly acute at baccalaureate institutions, which are already facing higher discount rates and greater losses in net tuition revenue.

KENNETH E. REDD is senior director, research and policy analysis for NACUBO.