Over the past several decades, the CBO position has gained in scope and depth,” says Roger Bruszewski, vice president for finance and administration, Millersville University. Bruszewski’s lengthy experience at the Millersville, Pennsylvania, public comprehensive and doctoral institution leads him to add: “The higher education institution has become a more complex place, requiring more well-rounded skills.”

NACUBO’s 2013 National Profile of Higher Education Chief Business Officers supports such a description. The new report, sponsored by TIAA-CREF, updates demographic data and other CBO-relevant information—noting changes and trends since the inaugural survey conducted in 2010 (for more details on the initial report, see “Profile of a CBO,” in the November 2010 Business Officer).

Specifically, the 2013 Profile notes shifts and variations in educational attainment, pipelines to the CBO position, job tenure, and future professional plans. Understanding how these differences influence the current landscape and the next generation of business officers is important for ensuring the strength of higher education institutions.

Enhanced Education

During a time when many are questioning the value of postsecondary education, the younger generation of CBOs is arriving on the job with more credentials than ever before. According to the 2013 Profile, CBOs ages 45 to 54 are significantly more likely to have earned a master’s degree in business administration (MBA) and the certified public accountant (CPA) distinction than were participants in the earlier survey.

Reasons of responsibility and gender. The increased credentialing may stem from the need to stand out from other applicants in a competitive job market, or perhaps these degrees and certifications are necessary for the evolving role of the chief business officer. The latter speculation is supported by Bruszewski’s comments about more complex institutions. “The complexity requires CBOs with more well-rounded skills such as those related to technology, food service, auxiliaries, debt management, privatizing of functions, risk management, unions, and more. The MBA provides a broad background of education that will help the CBO deal with these emerging issues,” he says.

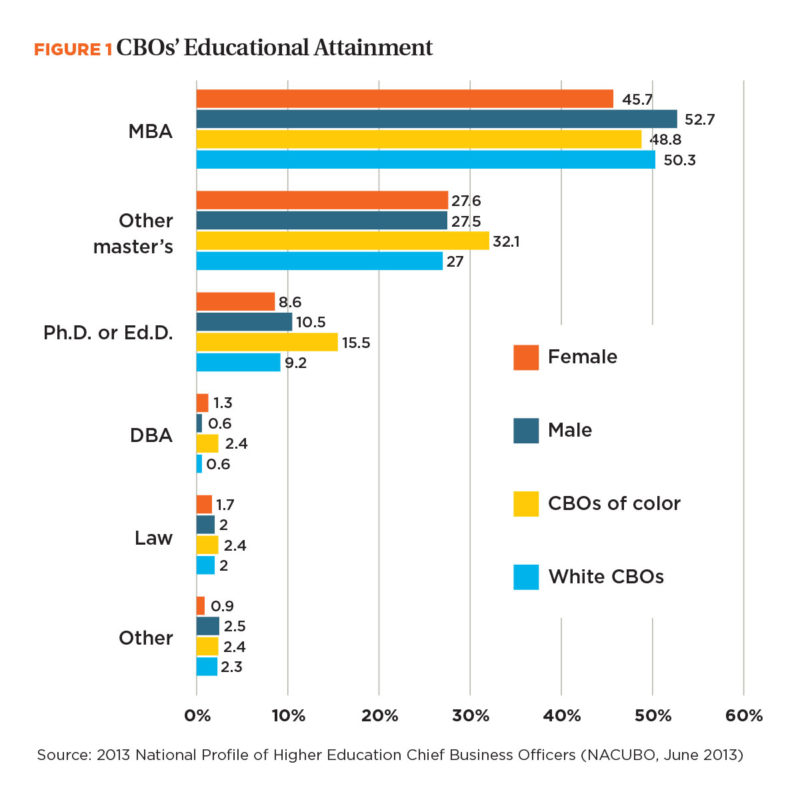

Interestingly, the 2013 Profile shows significant differences in educational attainment across population segments (see Figure 1). For example, female CBOs, two years younger on average than their male counterparts, are less likely to have earned an MBA. This may stem from the fact that when female CBOs were asked to identify areas of responsibility, they generally selected fewer areas than men did. With fewer women indicating physical plant, auxiliary services, public safety, and technologies as part of their current responsibilities, their positions may not yet align with the breadth of skills an MBA supports. In more traditional finance and accounting areas of responsibility (e.g., controller, budget, and internal audit), both men and women reported similar duties. Consequently, the survey reported no difference in levels of CPA certification related to gender.

Constituent characteristics. Educational attainment also varies among NACUBO’s four constituent groups: community colleges, small institutions, comprehensive and doctoral institutions, and research universities. Community college CBOs, for example, are much more likely to hold a two-year associate’s degree (perhaps along with other degrees and credentials), giving them a unique understanding of and appreciation for the community college mission.

Similarly, CBOs who have spent the majority of their careers in higher education are more likely to have earned a doctorate.

However, CBOs at small institutions —schools that generally do not award doctoral degrees—are less likely than those in other constituent groups to have earned a Ph.D. or Ed.D. Perhaps, notes Marta Perez Drake, NACUBO’s vice president for professional development, who was involved in the study, “the fact that more small institution business officers come from outside higher education may indicate that those institutions see as much value in different experiences as in certain degree attainment.”

Pipeline Particulars

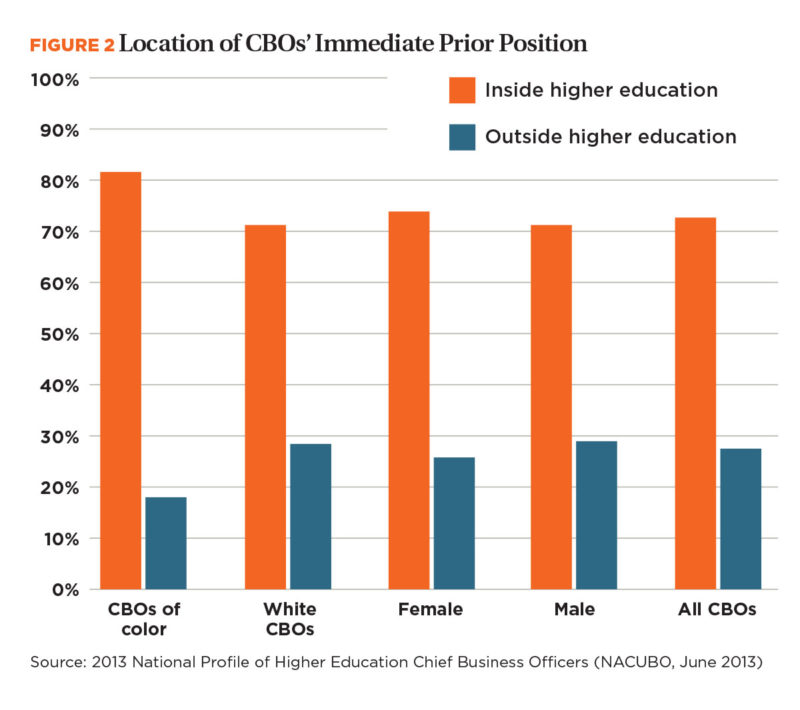

CBOs participating in this year’s survey reported a variety of professional experiences preceding their current positions, although for many, those jobs were within the higher education industry (see Figure 2).

- Fourteen percent have worked exclusively in higher education.

- More than 70 percent of CBOs came directly from another position within higher education. Of this group, the plurality

(35 percent) represented chief business officers at another college or university. This lateral movement puts additional constraints on the pipeline for younger employees seeking their first CBO positions. - Seventeen percent had no higher education experience before assuming the CBO role.

Relative to constituent type, business offices at small institutions are significantly more likely to be led by someone without any higher education experience (23 percent of CBO participants from small institutions); while research universities are the least likely (at 9 percent of CBOs reporting in this category) to employ a CBO without prior college or university experience.

On the other end of the spectrum, 25 percent of CBOs at comprehensive/doctoral institutions reported working exclusively in higher education.

Other characteristics at play. As Figure 2 indicates, CBOs of color are significantly more likely to move into the top business office position from other posts within higher education. Other survey responses revealed that CBOs also tend to move between and among similar schools. For example, the vast majority of CBOs at community colleges come from associate’s colleges; those at research universities come from doctorate-granting universities.

Furthermore, approximately three out of four CBOs at both public and private institutions come from the same sector. Similarly, CBOs who came directly from outside of higher education tended to remain within the public or private sector where they had been working. That is, CBOs at private institutions mostly came from private-sector businesses, including accounting firms, while those at public institutions were more likely to come from government jobs or the military.

These observations provide additional insight into the recruitment and selection processes at colleges and universities, and how specific skills and experiences influence business officers’ likelihood of advancing within particular sectors.

A professional boost. In addition to examining the pipeline, it is important to understand the role and methods of mentorship. While only a fraction of CBOs listed mentoring as one of the two most important CBO duties (the top choices were management of the institution’s resources and strategic decision making), interviews with chief business officers underscore the importance they place on mentoring the next generation of higher education business officer leaders.

In addition to discussing professional development goals, CBOs note the importance of including their mentees in board meetings and discussions that expose them to the importance of working with various entities on campus. Explains Mary Herrin, vice president for administration and finance, Wichita State University, Kansas: “These meetings provide a broader knowledge of the issues and responsibilities that are required of the CBO. Having an open staff discussion helps directors in the administration and finance team to think outside of their respective areas in the solution of an issue. It is important to have a greater appreciation of your colleagues’ responsibilities, as it adds respect for where your colleagues are coming from when they take certain positions. These discussions lead to both a better solution to an issue, and at the same time, make the team aware of the breadth of the CBO’s responsibilities.”

Tenure, Tension, and Turnover

The average time a CBO spends in any one position is approximately eight years, that number having increased by about one and a half years, compared with the 2010 Profile findings. Some CBOs have speculated that the increased tenure and average age relates to an older generation of CBOs holding off on retirement as they wait for their retirement and pension plans to recover from the recession.

Another contributing factor to increased length of service may be CBOs’ persistent job satisfaction, with approximately 90 percent of CBOs participating in the 2013 Profile reporting that they are “satisfied” or “very satisfied” with their current roles. Despite these extremely high ratings, CBOs still leave their positions for other opportunities, most commonly for the chief business officer position at another institution (25 percent of CBOs made this lateral move to their current jobs). Some may make this lateral move because they seek a new challenge or a larger campus, have grown frustrated with budgetary constraints at their institution, or have experienced a change in campus leadership.

“When I look at the careers of my CBO friends, we all have moved at least once in the past 10 years,” says Millersville’s Bruszewski. “We move for many different reasons. The most common is a new president arriving at the institution and wanting to bring his or her own person. Some CBOs move for financial reasons (more money); family (marriage or a spouse changing jobs); a new adventure; and/or health reasons. Just because a CBO moves to another institution, it does not mean he or she is unhappy or unsatisfied with the role of the CBO.”

Despite this general satisfaction, specific sources of frustration on campus do influence the CBO’s career decisions.

Culture and budget issues. Forty-two percent of participating CBOs reported being frustrated with a campus culture that resists change, while 38 percent said they were aggravated by budgetary constraints. When asked to identify the most important factor for remaining in their current positions, the plurality of CBOs (28 percent) indicated the ability to implement change. CBOs at comprehensive/doctoral institutions were significantly more likely than their peers to cite this factor, while the oldest group of CBOs (age 65 years or older) was significantly less concerned with implementing change. Those in the latter group were also much more concerned with being appreciated for their work.

Compensation counts. Generation, gender, and ethnicity influence perceptions of compensation fairness. CBOs ages 45 to 54 were significantly more likely to cite compensation as a key factor, while those 55 to 64 were less likely to consider compensation as most important. Community college CBOs were more concerned with compensation than CBOs at other constituent groups. And, while women were less concerned with money than men, they did put a high priority on the ability to implement change, while CBOs of color noted compensation as being more important than did their white non-Hispanic counterparts.

Expectations versus reality. A misalignment of expectations between the CBO and his or her president or board also poses challenges. While 77 percent of CBOs believe managing the institution’s resources is one of the most important roles, 87 percent believe their boards think this is the most important duty of the CBO. The opposite phenomenon exists when rating the importance of strategic thinking and decision making on campus. Thirty-nine percent of CBOs rate this kind of leadership as one of

their most important duties; however, business officers believe that their presidents and boards do not think this is one of the most important aspects of the CBO position.

Nevertheless, mutual understanding of the CBO’s specific roles on campus—along with open lines of communication between the CBO and campus governance—is crucial to the success of an institution. “My relationship with the president and the board is critical to my success as a CBO,” says Ronald Rhames, senior vice president and chief operations officer, Midlands Technical College, Columbia, South Carolina. “I have almost as direct interaction with the board as does the president. I think the board understands my role as a CBO, but at the same time they see me as an extension of the president. Thus, mutual trust and clear communication are important, because the president has to feel that there is consistency in the way we think on matters of board inquiries.”

Future Professional Plans

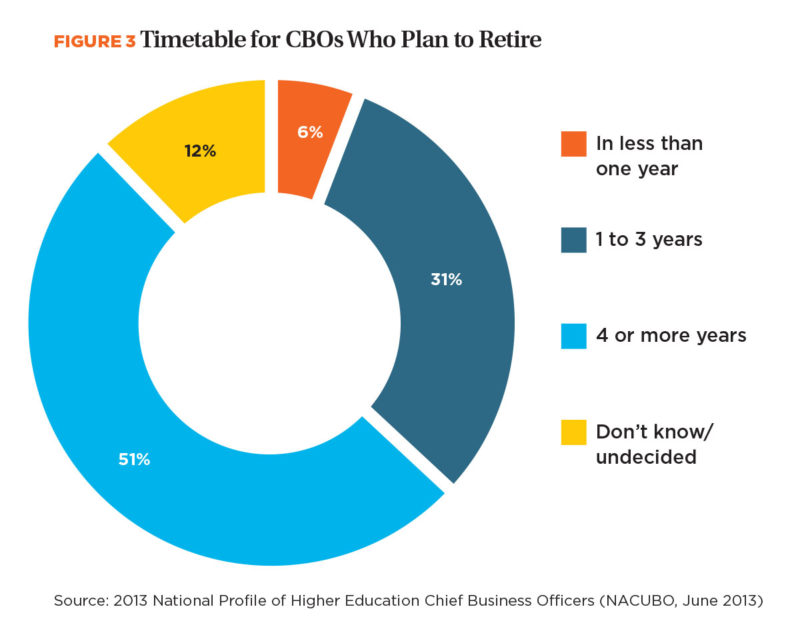

The average age of college and university CBOs has increased from 54 to 56 years since the inaugural CBO Profile in 2010. Specifically, the proportion of CBO participants who are age 65 years or older doubled to more than 11 percent. Closely related to the aging population is the increased number of CBOs who plan to retire, with 40 percent of current CBOs anticipating retirement as their next career move. Of this group, 6 percent plan to leave this year and another 31 percent plan to leave within four years. While the plurality of CBOs plans retirement as their next career move, others are expecting to leave their current posts for new jobs.

Including all CBOs who expect to leave their current positions—be it for retirement or career changes—37 percent expect to vacate their position within four years. This substantial potential turnover necessitates a serious examination of the pipeline to the CBO position.

By age 59, CBOs are more likely to retire than continue their career in another position. While this may be the tipping point at which CBOs tend to settle into their roles for the remainder of their careers, the study did find that CBOs of color and women are significantly less likely to plan on retiring as their next career move. Although they do plan to leave the CBO position at an equal rate to their male and white counterparts, respectively, these two groups are more inclined to plan on making a career change.

It is interesting to note that while these groups are underrepresented in the CBO population, they do not strive to make the CBO role the capstone of their careers. Perhaps this indicates that women and persons of color who are entering this role differ greatly in their professional goals than men and white non-Hispanics who take and hold the position.

This deeper understanding of issues affecting CBO retirement patterns is just as important as the awareness of changes in demographics, educational attainment, the pipeline to the CBO position, and job tenure. The recognition of the differences that exist between younger CBOs and the older generation also helps NACUBO understand how to prepare rising business officers for the changing role of the CBO.

An educational experience NACUBO has developed to help business officers get off to a good start is the New Business Officers Program (NBO), scheduled for the two days prior to the NACUBO annual meeting. “This workshop enabled me to hear from, and be inspired by, experienced chief business officers, presidents, provosts, and other key leaders in higher education,” says Connie Kanter, chief financial officer and vice president for finance, Seattle University. Kanter, who attended the 2012 program, adds: “The program provided an excellent overview to the issues I face as Seattle University’s CFO. I still use things I learned and am still in touch with colleagues I met at NBO.”

Interactions such as these are key to addressing the needs of the next generation of business officers and ensuring strong leadership in the business office for years to come.

JAMES D. WARD is research analyst at NACUBO.