In spring 2020, the University of North Dakota, Grand Forks, will replace its 100-year-old, coal-fired steam plant with a natural gas facility. That change alone will significantly improve the institution’s carbon emissions. Yet Jed Shivers, UND’s vice president of finance and operations and chief operating officer, acknowledges that reducing the school’s environmental impact—not to mention saving money on utilities—can be difficult on a campus full of aging, often inefficient buildings. One solution: consolidate and reconfigure campus spaces to maximize their use, which also reduces operating costs and minimizes risks associated with older structures.

“Substantial new construction occurred at UND in the 1970s and 1980s, and even more space came online within the last five to 10 years,” Shivers explains. “With an increasing shift to online education and improved efficiency in the use of our current educational spaces, however, we now have buildings that are empty or soon will be.” A number of those buildings carry high price tags for deferred maintenance, so UND has identified them as prime candidates for demolition.

“One way to cut operating expenses is to get rid of buildings that have gone past their useful lives, although we try to preserve historically significant buildings when they meet our programmatic needs,” Shivers says. “The future is not necessarily to replace aging buildings with something new but to be as efficient as we can with existing space.”

For the University of Massachusetts Lowell, state funding for capital projects has significantly decreased in recent years. At the same time, the university has been transforming itself into a full-scale research institution, which has called for reconfiguring many instructional spaces to house lab functions. “It would have been nice to build new, from the ground up, to meet the research space needs which come with that change in identity. But, with our debt capacity getting close to its ceiling, we don’t have that option available,” says Adam Baacke, executive director of planning, design, and construction at UMass Lowell. “We still have the same structures in place and so are doing the best we can to refresh and, ideally, renovate those spaces as we reprogram them.”

Whether driven by oversupply (or undersupply) of campus facilities, programming or enrollment changes, budget constraints, and/or sustainability concerns, many institutions have recognized the necessity to better use space in order to delay—or perhaps avoid—the need for new construction. Here’s a look at how that is playing out on several campuses.

In a Tight Spot

In 2011, the University of California, Davis embarked on a strategic initiative to add 100 faculty members and 5,000 undergraduate students by 2020—which put additional pressure on already well-used campus facilities. As enrollment grew, the registrar’s office found it increasingly difficult to find enough classrooms, even as the facilities staff issued assurances of adequate space.

In fact, the two groups were applying different metrics and therefore coming to different conclusions, says Jason Stewart, assistant director of budget and institutional analysis. The capital planning team used a general seats-per-student calculation for the whole campus, while the registrar’s office focused on how many 25-seat and 100-seat classrooms were available at a particular time, often coming up short. Desperate for general classrooms, the registrar’s office began using whatever space was available—including the performing arts center and a basketball gym. “We were very pressed for space, which most people found annoying and faculty really disliked,” Stewart says.

UC Davis asked its institutional research office to bring a fresh perspective to the situation. IR staff spent six months gathering and analyzing data, then organized the findings into a heat map that visually illustrated the percentage of general classrooms occupied and their capacity utilization

by time of day and day of the week. That data-driven exercise did not always substantiate anecdotal evidence, such as many classes being taught after core hours and at night. It did, however, confirm the space pressures reported by the registrar’s office.

Perhaps not surprisingly, the majority of classrooms were booked solid between 9 a.m. and 4 p.m. on Mondays through Thursdays yet remained unused at 8 a.m. and on Fridays. “UC Davis offers a lot of flexibility on class scheduling and, over time, that has allowed people to create a lot of Monday–Wednesday classes,” Stewart observes. “That’s unlikely to change soon, but at least the data visualization helps tell the space story and has created some good conversations.” Thanks to the color-coded presentation of data, those conversations all employ a consistent language; UC Davis has retired its seats-per-student calculation in favor of room occupancy and utilization percentages. The model built by the IR staff not only shows current room usage, but also illustrates future enrollment scenarios, which have proven helpful in designing new buildings.

Room to Spare

The University of Arkansas–Fort Smith finds itself at the other end of the spectrum from UC Davis, with more space than it currently needs. “We’re a young university that did a lot of building and is now in the midst of an enrollment decline because of demographic challenges,” says Brad Sheriff, vice chancellor for finance and administration at the school, which transitioned from a two-year to a four-year institution in 2002 and joined the University of Arkansas System a few years later. “Money wasn’t available beyond the facilities operating budget so, over time, deferred maintenance compounded.”

Sheriff estimates that the university has about 1.2 million square feet of facilities, more than enough for its total enrollment of 6,300, which includes off-campus students. Deferred maintenance on the buildings—many of which were constructed in the 1960s and 1970s—totals approximately $100 million. For an objective view of the situation, the University of Arkansas–Fort Smith participated in the Return on Physical Assets (ROPA Plus) program offered by Sightlines, a Gordian Company. The program helps institutions define their strategic decision making around campus planning and investments. “They walked the campus and looked at the physical condition of every building and also assessed the age and quality of the furnishings and ed tech in the classrooms,” says Sheriff. Using two years’ worth of scheduling and enrollment data, Sightlines provided metrics on room and capacity utilization.

Surprisingly, the analysis showed some of the oldest buildings on campus filled to near capacity while newer classrooms remained underutilized. “It’s possible that using certain classrooms has simply become ‘comfortable’ for faculty, who select where and when they will teach. Moving away from decentralized scheduling could help us improve space utilization and enhance the learning experience by putting more students in nicer spaces,” says Sheriff. The data, he adds, also pointed to the need for greater uniformity in building hours and investments in building automation to better manage utilities.

“We went from famine to feast in terms of having actionable data, and it will take time to change our practices and decide on formal space utilization policies,” says Sheriff, who already has an aging general classroom building in his sights for demolition. To date, space-related conversations have been conducted by the chancellor, cabinet, and academic deans. That group made a major decision 18 months ago when it adopted a new approach to physical space: no net new. In other words, until the campus needs more space, the University of Arkansas–Fort Smith won’t build anything new without taking an equivalent amount of square footage offline.

The Cost of Space

Like the University of Arkansas–Fort Smith, the University of North Dakota had a hefty amount of deferred maintenance: $500 million. In the last few years, UND has removed about 286,000 square feet—equivalent to canceling $53 million of those deferred maintenance costs. It still plans to remove another 929,000 square feet of space.

Much of the motivation for the downsizing, says Jed Shivers, has flowed from the university’s implementation of a responsibility centered management (RCM) budget model. Historically, space was a closely guarded asset that primary units—defined as any unit that generates income—rarely shared with UND’s broader campus community; the more space a primary unit controlled, the better. “There was no cost associated with possessing the space, no matter how much—or little—it was utilized. The space assignments were historical, with no guidelines about the size of classrooms, offices, or anything else,” notes Shivers.

That situation began to change when UND began to implement its Model for Incentive-Based Resource Allocation (MIRA). Phased in over four years, MIRA calls for each primary unit to pay a proportion of the facilities management budget, according to its assigned square footage. The calculation, based on each unit’s gross measure of square feet, doesn’t take into account the space’s age, quality, or maintenance requirements. “For the first time, the primary units did a complete inventory of all their space. Knowing there was now a cost associated with space, they started to turn over direct control of some space to the registrar so it would be removed from their allocated cost pool,” Shivers explains. Concurrently, UND gathered data that put its classroom utilization rate at 35 percent—compared to a state standard of 67 percent and an internal target of at least 80 percent.

UND’s first round of building demolition boosted room utilization to 50 percent during peak periods (Monday through Thursday, 9:30 a.m.–2 p.m.). The planned demolitions, once accomplished, should bump utilization to about 67 percent. They will also free up real estate for potential P3 investment. “Some new space will come back—but not a lot—and we’ll end up with a smaller campus,” observes Shivers. “One of our strategic goals is to create a more vibrant campus community by bringing more students here not just during the day but also to live.” To that end, UND is reviewing housing options and recently tore down its Memorial Union to rebuild a new facility on the same site. The original student union, built in 1951, had carried more than $40 million in deferred maintenance.

Constructing the new student union will cost about $80 million and is the result of a five-year effort driven by the 10,000 students on UND’s physical campus. “The majority of students voted for an increase in student fees to pay for a new, improved union as a place for them to meet each other and with faculty,” Shivers says. “We regard that as a very positive sign—UND is a place people want to reinvest in.”

Review, Repurpose, Reconfigure

Enrollment is growing faster than available space at the University of Massachusetts Lowell, where a state funding freeze has limited its ability to undertake major capital projects. The solution: Do smaller-scale, incremental retrofits and renovations that still align with the institution’s guidelines for space occupancy, usage, and sustainability. For classrooms, for instance, UMass Lowell tracks a utilization metric that’s similar to a batting average; using the weekly student contact numbers, the calculation combines both room fill and seat fill. A slightly different metric is used for lab spaces, where scheduling windows take precedence over seat fill.

Every few years, the university surveys faculty members about their likes and dislikes regarding instructional space. “The results usually give us insights into what we need to pay attention to and help inform everything from classroom furniture purchasing to space allocation decisions,” says Adam Baacke. He notes that the registrar controls nearly all instructional space (excepting specialized labs and studios) and does centralized scheduling. Rooms that aren’t well-used or well-liked for instruction often become targets for repurposing. One oddly shaped classroom, for example, may be reconfigured with work stations for graduate students and research staff. Several other classrooms, created out of a gymnasium, never had an effective HVAC system, making them uncomfortable environments. Baacke explains, “We’re taking those unpopular spaces out of the classroom inventory and converting them into a robotics lab—almost restoring the original gymnasium space.”

Questions about space allocation and assignments, as well as prioritization of capital projects, are handled by UMass Lowell’s space management committee. Co-chaired by the chief financial officer and the vice chancellor of research, the committee meets every two weeks and includes several members of the executive cabinet—the group that makes the definitive decisions related to space. In recent years, those decisions have included:

- Expanding the scheduling windows. Some UMass Lowell departments now offer evening or Saturday morning classes. “Interestingly, people have discovered that these nontraditional times are quite appealing to a certain segment of the student population,” says Baacke. For example, Saturday seminars have proven popular among freshmen honors students in engineering or the sciences, who often must follow a rigid, prescribed schedule of classes during the week.

- Supporting active learning. As buildings are renovated, some conventional, lecture-style classrooms are giving way to flipped classrooms that encourage project- and team-based education. These flexible spaces often include technology and modular furniture that can be configured in various ways. Although less space-efficient than traditional classrooms, says Baacke, such rooms are likely to be in high demand and therefore well-utilized throughout the week.

- Pursuing the suite life. When UMass Lowell completes its renovation of Coburn Hall next year, the 122-year-old building will include two suites for graduate students and adjunct faculty. “We want to move away from the one person/one cubicle model to a suite of rooms featuring shared but larger work stations, a meeting table for group engagement, soft seating, and some huddle rooms to provide privacy and locations for holding office hours,” Baacke explains. “It’s unlikely all the graduate students or adjunct faculty will be in the suite at the same time. When they are there, they’ll have more tools to work with when compared to a room full of identical cubicles.”

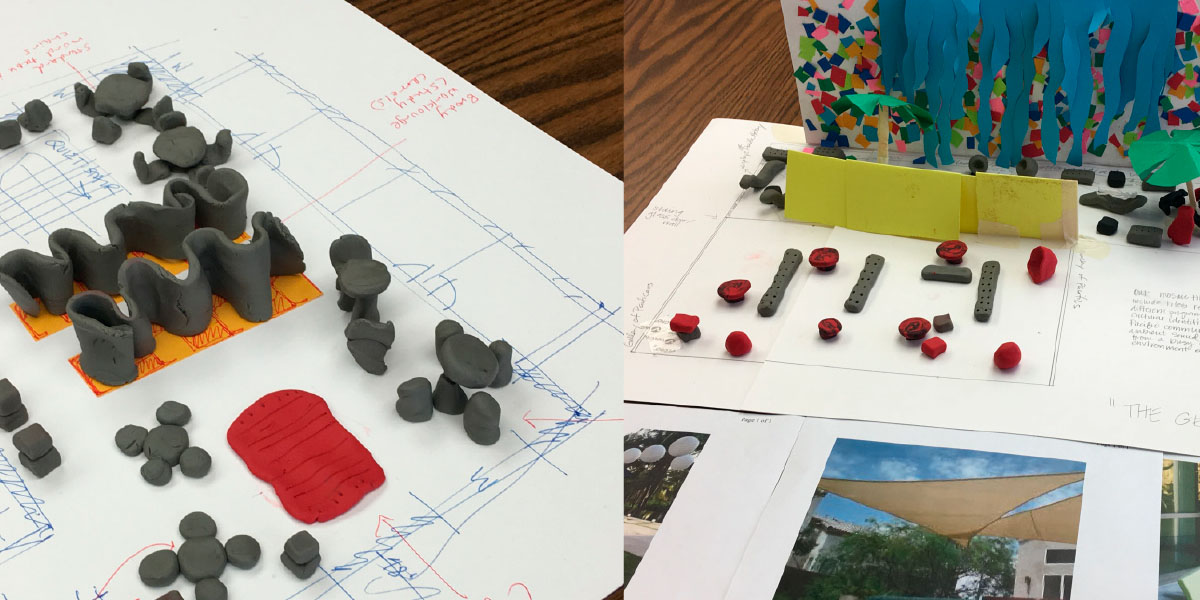

- Programming for communal activities. UMass Lowell is intentionally designing more spaces that encourage community-building and socialization among students. Baacke notes, “Our new residence halls devote greater square footage to functions that are not sleeping and studying, and we’re looking for ways to create outdoor spaces that support engagement as well.” In addition, the university has transformed its library into a learning commons that features a coffee shop and numerous places for individual and group study.

Moving Pieces

Similarly, Swarthmore College, Swarthmore, Pa., decided to open up the first of its library’s four floors to accommodate greater student interaction and digital scholarship. Doing so, however, required space reallocations and relocations. First, Swarthmore reduced by 50 percent the lower-level space devoted to its collection of government documents; it added more compact shelving and purchased more materials digitally. That provided enough space to move Swarthmore’s entire collection of bound periodicals—which have fairly low usage—to the lower level. With the periodicals relocated, the second floor could house the well-used honors reserve collection, which had been on the first floor.

“In talking to students, we found they loved the concept of a traditional reading room that was quieter than the open spaces on the first floor and had a seriousness of purpose about it,” says Peggy Seiden, Swarthmore’s academic library director. “In addition to the reading room lined with bookshelves and large tables, we brought in open and soft seating, group study rooms, and enclosed study spaces.”

The biggest change to the 52-year-old library involved significantly downsizing space for technical services and relocating that function to the second floor. “The work of library staff has changed tremendously because we do a lot more with electronic materials. Over the years, many of the staff lines in technical services had been repurposed to other library functions, and the space devoted to technical services had become cavernous and underutilized,” Seiden notes, adding that technical services occupied prime first-floor real estate. Ultimately, Swarthmore decreased the square footage dedicated to that function by almost 50 percent, without sacrificing comfort or functionality. In fact, all eight staff members now have private offices larger than their old cubicles, and their noisy equipment is no longer in the open but contained in an adjacent, acoustically controlled workroom. Technical services now has its own conference room, located just outside its second-floor suite of offices, which is left open for student use in the evenings.

Seiden used the library’s renovation to rebalance and reorganize reporting relationships as well. Pairing architectural and other changes is natural, confirms Marie Sorensen, principal-in-charge at Sorensen Partners, the architectural firm in Cambridge, Mass., with which Swarthmore consulted. “Jobs often change at the same time an architectural redesign happens, because it’s about more than just moving desks around. Whatever you do architecturally can lead to exciting discussions about people’s needs, the culture, productivity, how people work together, and group cohesiveness,” says Sorensen. “Redesigning or reorganizing space can be transformative, and not just in the sense of the physical world.”

SANDRA R. SABO, Mendota Heights, Minn., covers higher education business issues for Business Officer.