Today’s national coalition of student and faculty voices calling to divest fossil fuels from collegiate endowments brings to mind the spring of 1977 and the early days of Stanford’s antiapartheid movement. As an undergraduate, I joined in the demonstrations and calls for the divestment of Stanford’s endowment from South African securities. The movement spread from college campuses to the White House, becoming an important catalyst in the downfall of the apartheid regime and the release of Nelson Mandela.

Today’s national coalition of student and faculty voices calling to divest fossil fuels from collegiate endowments brings to mind the spring of 1977 and the early days of Stanford’s antiapartheid movement. As an undergraduate, I joined in the demonstrations and calls for the divestment of Stanford’s endowment from South African securities. The movement spread from college campuses to the White House, becoming an important catalyst in the downfall of the apartheid regime and the release of Nelson Mandela.

At the time, supporting the movement felt so clearly to be the right choice. Nearly 40 years later, history has validated that decision many times over. Yet, while there are striking similarities, fossil fuel divestment is a very different issue with many factors at play. Regardless of one’s views on the appropriateness or impact of fossil fuel divestment, fully understanding these factors presents substantial investment opportunity and potential portfolio gain.

The critical role that universities continue to play in incubating new and disruptive ideas—both social and technological—is also undeniable. Many students today are moved, as I was, to work at the edge of change. My Stanford experience, along with many others in my life, led me to pursue impact venture capital—identifying the next business innovation cycle, capitalizing on those changes for our firm’s investors, and all the while working to promote social and environmental improvement. Young people, acting as both students and consumers today, push for support for their own ideals, which often include environmental and social concerns. But there is more to the story: The innovation cycle currently occurring in clean energy, and its relationship with contemporary campus movements, is deeper than many realize.

A Growing, Modern Movement

The speed and support for today’s movement to divest fossil fuels caught both administrators and investors off guard. Catalyzed by social media, the campaign counts more than 300 active campuses and has successfully driven full divestment for eight endowments thus far.

The images of student sit-ins on campuses like Washington University in St. Louis are striking. In this case, the call is for a divestment of the endowment and the removal of Peabody Energy’s CEO, Greg Boyce, from the board of trustees. Washington University students made Peabody and Boyce the public target of their divestment campaign after a successful February 11 lawsuit by Peabody, which blocked a St. Louis ballot initiative to end tax incentives for fossil fuel companies and invest public money and lands in renewable energy and sustainability initiatives.

The movement is certainly not limited to students. In early April, 93 Harvard University professors sent an open letter to their administration calling for divestment. Archbishop and Nobel Laureate Desmond Tutu, who was active in the antiapartheid divestment movement, recently endorsed fossil fuel divestment, citing global warming as the human rights issue of our time. Today’s movement is also the fastest-growing divestment campaign in history. By comparison, the antiapartheid divestment movement took 10 years to spread to 165 universities.

Repositioning Responses

Divestment itself is not the main event, but rather a subset of broader conversations many institutions and their stakeholders are conducting about overall commitments to sustainability and what is referred to as a “cleantech” transformation. An ever-increasing number of colleges and universities are seeking to reduce their carbon footprint significantly via renewable energy sources, recycling, sustainable food, and the like. That is one catalyst for shifting investments from fossil fuels to clean technologies. The other driver is the opportunity to produce strong financial returns by building a portfolio of cleantech assets.

A salient example of combining both catalysts is Pitzer College, Claremont, California, which recently announced a broad sustainability initiative that includes divesting fossil fuel investments from the endowment. At the same time, the plan calls for establishment of a sustainability investment fund, reaffirming the college as a green campus leader. Pitzer has also set aggressive sustainability goals, with a target carbon footprint reduction of 25 percent over the next two years.

Universities are embracing a variety of sustainability options, including green building construction and installation of independent electrical systems called microgrids, which often combine distributed renewable energy—such as solar—with advanced energy-storage and energy-efficiency measures. In fact, the University of California Davis has established a new campus neighborhood known as West Village (http://westvillage.ucdavis.edu), which is the largest planned net-zero energy community in the United States. The $280 million project is a public-private partnership that has resulted in projected energy savings of 50 percent over current building codes. (For more details, see “It Takes a Village,” in the July/August 2013 issue of Business Officer.)

Making the Investment Shift

The good news for institutions considering a rebalancing in their portfolio—to reduce fossil fuel exposure and boost sustainable initiatives, is that it may be easier than expected. Donald Gould, Pitzer College trustee and chair of the college’s investment committee, guided the college’s landmark endowment divestment decision. He argues that divestment not be viewed as a binary decision, but rather as a continuum of options to reduce fossil exposure and invest for sustainability.

Using the analogy of a daily commute, Gould notes that many options exist between the two extremes of a lone driver making a 20-mile commute to work in an SUV, and a person riding a bicycle on the same route. Similarly, universities can choose from a wide array of options to reduce their dependence on fossil fuels and expand their use of cleantech practices.

This anecdotal comparison is supported by several institutional studies, including research by the Aperio Group. The research found that a range of options—from excluding coal stocks to broadly divesting all fossil fuels—had a negligible impact on both endowment returns and volatility. These findings are important for universities considering divestment, which, in total, would shift billions of dollars out of fossil stocks. Fortunately, although the total amount is large, only four percent of university endowment holdings, on average, are in fossil fuels. Endowment officers can rest assured that reducing fossil exposure and prioritizing sustainability need not trade off with achieving financial security for universities, nor does it require a drastic rebuild of their portfolios.

That is another reason why Pitzer College made its divestment decision in the context of a set of sustainability measures intended to align with the college’s long-term perspective—which is one with fewer fossil fuels and more renewables. The decision came at the recommendation of a campuswide taskforce to evaluate sustainability from a policy perspective. It was not until after the college identified its policy stance on sustainability that the leadership evaluated how to incorporate that value into the college’s investment structure.

Gould believes that each institution needs to decide for itself how important sustainability is to the community, and then evaluate how that should drive its investment decisions. Pitzer is an example of sustainability and divestment initiatives that incorporated the perspectives of all campus stakeholders, with strategic changes to be implemented in phases with interim objectives.

As Gould notes, policy decisions regarding divestment are unique to each school. For business and investment officers who are interested in shifting their portfolio, the following represent some first principles in making a portfolio more sustainable:

- Develop a time frame that meets the institution’s needs.

- Build a continuum of risk and reward across a variety of asset classes.

- Lay out divestment goals across risk and liquidity requirements.

- Determine the relative roles of passive and proactive investments, as well as negative and positive screens.

- Test the market with smaller allocations, and build from there.

Climate Change, Stranded Assets

The case for fossil fuel divestment is not a matter solely of sustainability concerns—in fact, many believe avoiding carbon exposure is important for managing portfolio risk. Bill McKibben, a prominent environmentalist and the founder of 350.org, outlined this case in his “Do the Math” campus tour of 21 cities, which helped spark the divestment movement.

His argument goes like this: To avoid catastrophic impacts of climate change, the United Nations has declared an allowable amount of greenhouse gas emissions—our “carbon budget”—that would keep the globe below 2 degrees centigrade warming through 2050. According to McKibben, any warmer than that “risks catastrophe for life on earth.”

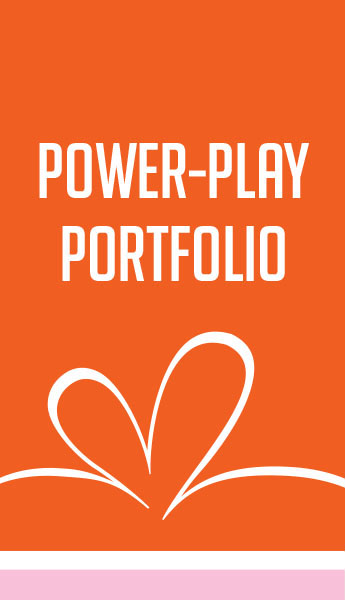

Here is the problem: Our global budget of 886 gigatons (Gt) of CO2 is a small fraction of the proven carbon reserves held by fossil fuel companies, and we have already used more than 321 Gt. In fact, global fossil fuel companies have proven reserves of more than 2,900 Gt CO2, or more than four times our remaining budget of 565 Gt CO2. Thus, if we are to prevent the climate from exceeding the two-degree limit, we can only burn about 20 percent of what has already been discovered in the ground. Assuming our carbon budget is enforced, most proven reserves are unburnable and likely to become “stranded assets” (see Figure 1).

Carefully Evaluating Carbon Risks

The specter of this looming “carbon cliff”—beyond which we cannot continue to burn reserves—represents a substantial systemic risk to the fossil fuel industry. As it turns out, students are not the only ones concerned about that risk. Known as the Carbon Asset Risk Initiative, a group of 70 global investors—including the California Public Employees Retirement System (CalPERS) and the New York State Common Retirement Fund—representing more than $3 trillion in assets, recently called for fossil fuel companies to explain how financial risks and their business plans will change in a low-carbon future.

Anne Stausboll, CEO of CalPERS, echoed the sentiment, saying, “We have a fiduciary duty to ensure that companies we invest in are fully addressing the risks that climate change poses.”

Classifying environmental risks—including climate change—as part of an asset manager’s fiduciary duty is helping to update investors’ views of the fossil fuel sector. Today, the market calculates the values of fossil companies based on their current assets and future projected earnings streams, which are tied to the amount of coal, oil, and gas they have in the ground. If a major pool of reserves suddenly became stranded, the market capitalizations (the stock market value of a given company) and potentially the debt ratings of fossil companies would suffer a significant correction.

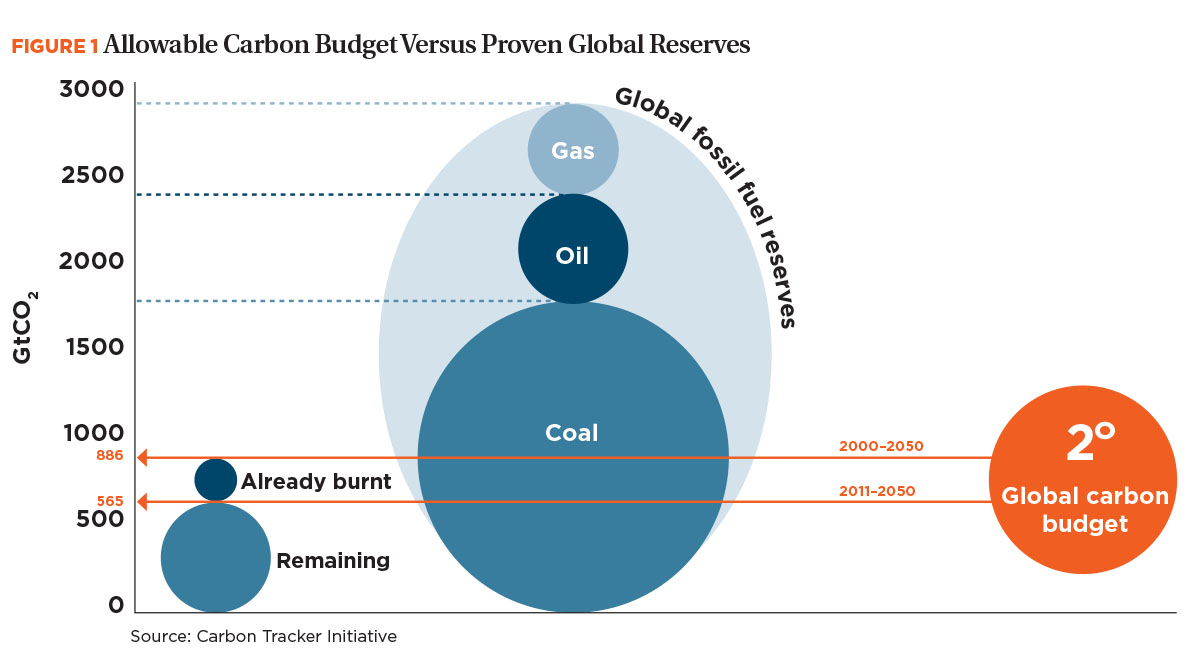

A rough estimation of the economic value of this unburnable carbon—potentially 80 percent of all proven reserves—suggests that nearly $20 trillion in carbon assets could become stranded. By comparison, the collapse of the U.S. housing bubble after the 2008 economic crisis wiped off $7 trillion in the value of American mortgages, and we have yet to fully recover from the lasting impacts of that crash. Thus, the projected perils of this “carbon bubble” have initiated a rethinking of risks associated with carbon assets (see Figure 2).

Position for Opportunity

While the carbon cliff creates portfolio risk, irrespective of policy and ethical views on fossil fuels, a compelling opportunity exists for strong financial returns generated from the assessment of risks related to climate change and the stemming development of a responsive investment approach that taps into the growing markets for renewable energy sources, energy efficiency, and clean technologies.

As a venture capitalist, the huge opportunity I see is related to the innovation cycle happening today in energy: For the first time in 100 years, we will not be reliving our grandfathers’ electricity industry as the basis for future innovation.

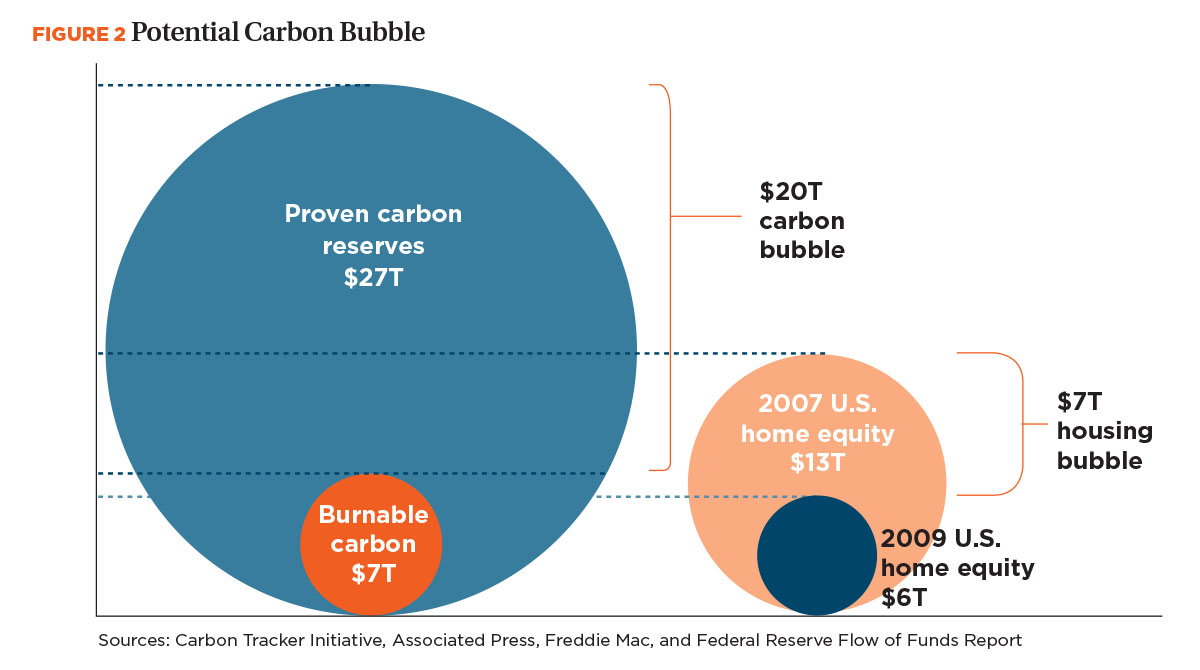

Over the course of our lives, we have witnessed several major innovation cycles across industries like computing, telecommunications, radio, and automotive (see Figure 3). The products and companies that grew out of these cycles have come to shape our daily lives in profound ways. Major revolutions of the past half century share themes of personalization, cost-reduction, decentralization, transparency, on-demand service, and convenience. Investing across these changes, while volatile and not without risk, has often been a beneficial place to be.

The same themes are present today in the energy sector. After 100 years of relative stagnation, the current evolution of energy is, in many respects, representative of a movie we’ve seen play out many times before across other technologies.

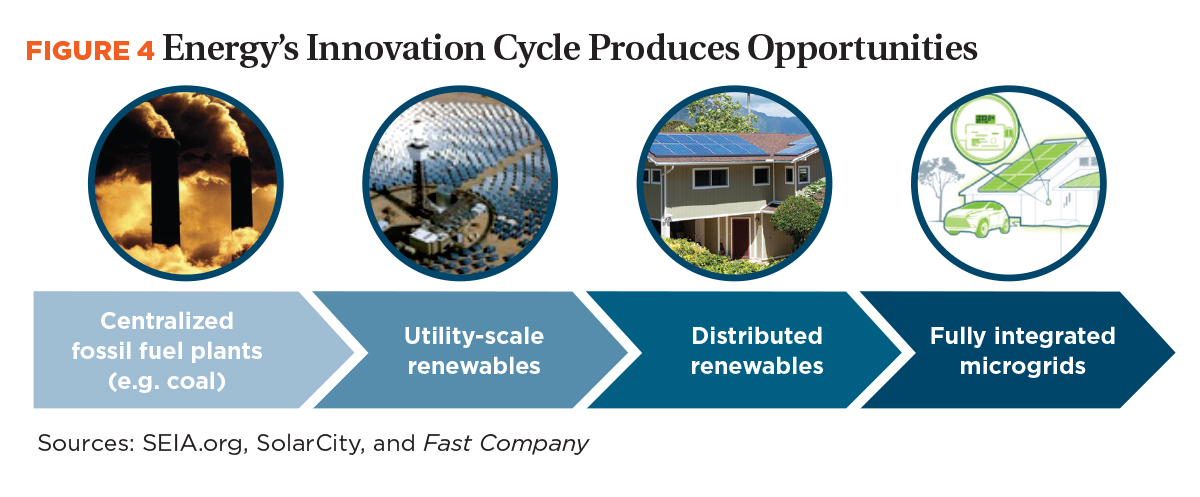

In the past decade alone, we have witnessed an energy transformation that took us from centralized fossil plants (including coal); to utility-scale renewable installations (like solar thermal); to distributed renewables (residential solar); and steps closer to the future of fully integrated microgrids for homes, businesses, and other institutions (see Figure 4). The cleantech sector is estimated to be a $2.56 trillion annual market today, rising to $5.13 trillion by the mid-2020s, according to the Climate Group. Given this unprecedented shift, it is clear that portfolios with concentrated energy investment in fossil fuels, without including no- or low-carbon alternatives, have so far missed out on the exposure to major pockets of innovation in the energy industry. Indeed, the oil companies today are likely to reimagine themselves as the “energy” companies of tomorrow.

Much as our taste for computing on laptops fueled our appetite for smartphones and tablets, strong consumer pull for cleaner products is helping to realize energy transformation. As the understanding of the carbon supply chain increases daily, shifts in consumer behavior are driving the demand for greener cars, cleaner electricity, better storage technologies, and a lower-carbon consumer products ecosystem that makes a dent in climate change.

On the supply side, consumers and businesses alike are waking up to the fact that reliance on fossil fuels leaves us with unknown future energy costs (even if they are relatively cheap today). Because the wind and sun are more or less infinite in supply, renewable energy provides price security, whereas it is reasonable to expect increased volatility in fossil fuel prices and more regulation of carbon. This volatility on the part of fossil fuels permeates the supply chains of many consumer and industrial products, putting traditional recipes for a host of products—from chemicals to packaging—at risk, and driving global demand for more transparent and sustainable product formulations and supply networks.

Innovation Impact on Returns

Innovation themes like decentralization are threatening to incumbents. The utility industry today faces challenges from renewables similar to those that telecommunications faced from wireless technology 20 years ago. The business risk declarations in their respective annual 10-K statements reveal the similarities of today’s energy transformation to that of telecom’s past.

But for investors who are riding the innovation wave, this is inherently good news. As new upstarts operate on a different logistical curve than their incumbents, they grow at much higher rates, providing the potential for substantial financial returns. Comparing the automotive- and energy-industry transformations, we can see that while a century separates the foundings of GM (with a March 31, 2014, market cap of $55.1 billion) and Tesla (at $25.7 billion); and PG&E ($19.7 billion) and SolarCity ($5.7 billion); in each coupling, the innovator has achieved approximately one third the market cap of the incumbent in a very brief time frame.

The clean energy sector is rich with technologies that will continue to drive opportunities in this innovation cycle. The next Tesla or SolarCity is already waiting in the wings, and one area in which we expect to experience unprecedented growth is the advanced energy storage (AES) industry. As we move to use fewer fossil fuels, we will need a solution that replaces on-demand electricity generation, since the wind will not always blow nor does the sun necessarily shine when we most need power. AES is one technology that will permit efficient and widespread integration of renewables into the grid. Energy startups pursuing new storage products have the potential to unseat incumbents while creating unique investment opportunities.

Something for Everyone

Cleantech investments are no longer limited to the domain of venture capital. In fact, the industry has matured to the point where traditional institutional investors can now participate across the risk spectrum, including exchange-traded funds, bonds, private equity, and real assets. Thus, regardless of one’s risk profile, there are myriad opportunities to gain exposure to innovation in clean energy.

For instance, Zurich Insurance Group—an international insurance company—has invested more than $1 billion in green bonds, making it the largest investor in such clean power securities to date. Furthermore, individual investors are realizing significant returns, with the NASDAQ Clean Edge Green Energy Index up 89 percent in 2013 alone. Financial innovations are also paving the way for new participants in cleantech investment. Both the securitization of solar leases and the advent of crowdfunding (via companies like Mosaic and CommonAssets, acquired by SolarCity) are some examples of new alternative investment routes for solar.

The rise of cleantech assets across the risk spectrum has been met with both growing enthusiasm by investors and notable returns in the market. Interestingly, over the five quarters ending March 2014, cleantech posted gains that dwarfed those of oil and gas, with the Wilder Hill Clean Energy ETF up 50 percent from January 2013 and the SPDR Oil & Gas Producers ETF up only 25 percent in the same period.

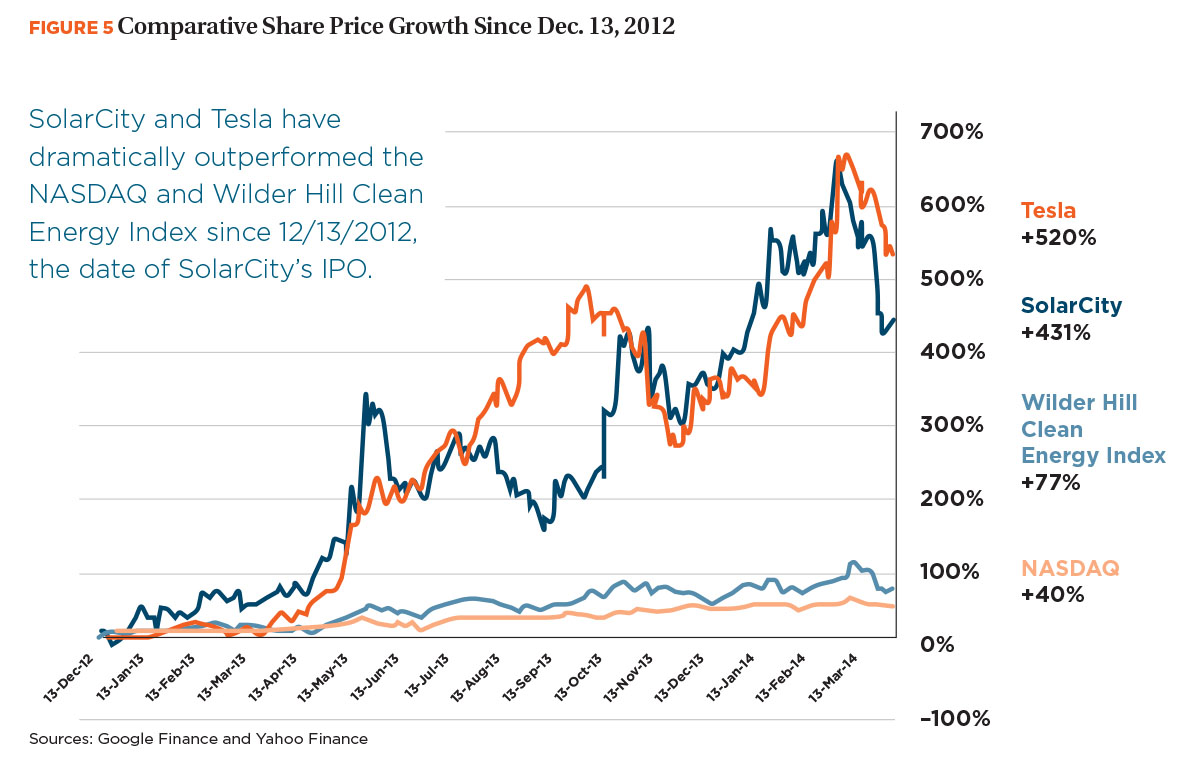

Additionally, the maturation of second-generation cleantech companies like DBL-backed Tesla and SolarCity achieved record results, dramatically outperforming both the NASDAQ and Wilder Hill Clean Energy Index since December 2012, when SolarCity went public (see Figure 5).

While institutional investors, including colleges and universities, are beginning to access new cleantech assets, they are also becoming increasingly aware of potential overexposure to carbon assets. HSBC Holdings has established a Climate Change Centre of Excellence, which helps investors analyze the strategic implications of climate change for investors. The center has found that a global peak in fossil use by 2020 “implies a 44 percent reduction in discounted cash flow value of fossil fuel companies,” or a decline in share price of 40 to 60 percent. Most recently, Stanford became the first major university to divest its $18.7 billion endowment from coal-mining companies, citing the availability of alternatives to coal that have less harmful environmental impacts. These are just a few examples of the many institutions and investors reassessing and reallocating to address carbon risks.

Social Impact as aBusiness Strategy

In the same way that investors profited early by embracing energy’s shift, companies are responding to the notion that going green is actually good news for their market position. Some companies are taking steps to disclose their carbon risks—such as Puma in its “environmental P&L statement,” which restates profits after accounting for climate impacts.

They are also leveraging sustainability as a key marketing differentiator. The launch of products like Intel’s “conflict-free” microchips (which will replace historically less sustainably made chips and exclude rare earth materials from countries with human rights violations); McDonald’s sustainable beef (which largely mitigates the footprint of its meat); and Safeway’s recycled paper bottles for laundry soap and wine, from Ecologic Brands, reveal that sustainability and supply chain transparency are relevant to consumers’ choice of brand. More recently, Apple initiated a “Better” ad campaign featuring its commitment to use greener materials, less packaging, and renewable energy sources to power its manufacturing and vast data centers.

Many of today’s energy opportunities lie in the new generation of consumer who not only values sustainability, but increasingly demands it as a product feature. In addition to environmental benefits, companies are embracing social impact in many aspects of business operations.

Facilities. For instance, woman-founded Ecologic Brands chose to locate its sustainable packaging manufacturing facility in the central valley of California, a region hit hard by the economic downturn, with 15 percent unemployment. Additionally, Tesla Motors’ 5,000-and-counting ranks draw from some former employees at the Toyota-GM NUMMI auto plant, which is now the Tesla factory. The NUMMI closure had previously sent shock waves through the regional economy in Fremont, California, before Tesla bought the facility.

Nutrition and community involvement. Revolution Foods, headquartered in Oakland, California, provides more than 1 million healthy, fresh, all-natural meals every week to schoolchildren nationwide, the vast majority of whom are from low-income families. The company, which is women-led, is located in a low- to moderate-income area of the city.

When management noticed that a high percentage of its employees were without bank accounts, it asked our firm to help implement financial literacy training and identify and secure matching funds for employees who opened bank accounts. To increase its ability to promote high-performing entry-level workers, we then assisted Revolution Foods in launching a program focused on vocational English as a second language.

The potential for bottom-line benefits from these programs is enormous and varied—higher employee retention, lessened expense for recruiting, lower cost of capital financing, and numerous tax incentives—all of which can enhance a company’s cost structure. More broadly, investments in human capital like these go a long way toward fostering functional families interested in and committed to higher education for their children.

Clearly, the opportunity for institutions to build strong investment platforms while addressing pressing social issues has many dimensions. For colleges and universities, the fossil fuel divestment movement can be seen as one way to infuse this diversification into the investment portfolios of tomorrow, while affording sustainable innovations the chance to grow in and around the campus today.

NANCY E. PFUND is founder and managing partner of DBL Investors, a venture capital firm in San Francisco. Her colleagues Michael Keaton and Sarah Ham assisted with this research project and article.