Universities and medical centers are among the world’s greatest sources of economic and social advancement. At the same time, these institutions face the need to maximize existing physical and intellectual resources in support of mission, while delivering efficiencies and innovative new business practices.

It may sound like an impossible undertaking—especially after years of cost-cutting—however, the approach illustrated in this article reflects the reality that many higher education institutions own underutilized or underperforming physical assets. While their value is not seen on the face of the balance sheet, because the assets are often waiting to be evaluated for new and emerging needs, when utilized effectively, they serve as resources for investment that support a university’s strategic plan and priorities.

Georgia Institute of Technology and Emory University, both in Atlanta, have done just this: unlocked hidden physical assets to deliver higher value. Although these institutions are both highly research-oriented universities, just five miles apart, they showcase the fact that both public and private institutions, individually and collaboratively, can engage in noncore, nontraditional, nonacademic enterprise opportunities to accomplish core mission objectives.

Emory University and Georgia Tech shared a strategic goal related to their libraries. Both were seeking new ways to generate investment capital; with Georgia Tech, a public institution, having the added responsibility of working within the authority of the University System of Georgia. The USG is a government agency that supports public institutions of higher learning in the state.

The programmatic and academic drive of each institution, coupled with new approaches to generate investment capital, have met with great success, allowing Georgia Tech and Emory to redirect both physical and programmatic assets—not only for their individual institutions, but collaboratively through combined initiatives. For example, the two universities created a joint biomedical engineering program that now ranks No. 1 in the country; and, most recently, their shared work on their respective libraries resulted in a state-of-the-art shared library service center.

Learn to Liberate Equity

During the years when Mike Mandl and Jack Tillman (co-founders of Mandl & Co.) were Emory executives, they began to see that the key to effectively reassigning assets is to think differently about equity and asset management. In the corporate sector, companies use equity as a tool. For example, a company can offer stock options to grant employees an equity ownership in the company. When it comes to higher education institutions and identifying equity, a crucial question is, “Where is the equity at institutions, and how do you liberate it in a way that doesn’t compromise mission but drives resources to program needs?” In other words, how do you unlock hidden equity that’s not readily apparent on a financial statement?

Universities can build, buy, or sell programmatic or physical assets to generate this dormant equity. Monetizing noncore services, assets, and operations can become more disciplined strategic tools. Following are key techniques and specific transactions employed by Georgia Tech and Emory to convert newfound equity into support for their respective goals.

Real estate development. Each institution found ways to leverage existing assets.

- One of Emory University’s strategic objectives is to increase graduate student, staff, and faculty multifamily housing near campus, while bringing more foot traffic and energy to the area via additional retail space.

The majority of housing near campus consists of single family homes that were largely unaffordable for most students, faculty, and staff. At the same time, university leaders did not want to take on the risk of an additional capital project, nor give up long-term land ownership.

After careful negotiation, Emory worked with a third party to build high–quality graduate and faculty housing, bring in retail stores, receive significant cash for the value of the land upfront—under a long-term ground lease—and preserve its land ownership. Named Emory Point, this mixed-use project has 750 apartment units with consistently high residential occupancy rates and 120,000 square feet of street-level retail. Third parties manage retail and residential rentals.

- Georgia Tech’s Technology Square project proved a great success from its start, beginning more than 15 years ago. The development connects Georgia Tech to the midtown Atlanta community while enhancing the physical presence of its business school and strong professional education programs in lifelong learning.

- With key land acquisitions in midtown by Georgia Tech Foundation, the institute created an innovation neighborhood, complete with a conference center, hotel, and retail, which invigorated economic development and engagement with the local community. Phase two of this initiative has led to partnering with a private company to develop the Coda Building. This nearly 750,000-square-foot, mixed-use project will create opportunities in interdisciplinary research, commercialization, and sustainability.

Owned by Portman Holdings, the building’s anchor tenant will be Georgia Tech, occupying about half of the 620,000 square feet. The project includes nearly 40,000 square feet of retail and an approximately 80,000-square-foot data center. The Coda Building, to be completed in early 2019, will enhance Tech Square’s innovation ecosystem by becoming a magnet for corporations and startups alike, while serving as a state-of-the-art resource for breakthrough research.

Asset monetization/intellectual property. There is value to be unlocked in intellectual property, outside the traditional form. For example, Emory had been receiving a royalty stream in the form of annual payments from a drug developed at the university. Emtricitabine (trade name Emtriva—with the “Em” for Emory) is among the most-used HIV/AIDS drugs worldwide, taken in some form by more than 94 percent of U.S. patients on HIV therapy and by thousands more globally.

In July 2005, Gilead and Royalty Pharma bought the university’s royalty interest in Emtricitabine—this inflow of funds was reinvested in Emory’s research programs and facilities. The new approach valued the annual stream and monetized it upfront. By selling the future royalty streams, Emory earned $525 million for this stream, well above the initial estimate.

Other partnerships. Partnerships with private companies of all types can be mutually beneficial.

- Emory partnered with the Atlanta Hawks basketball team, which was in need of a practice facility. This coincided with Emory’s desire for a sports medicine facility. With a ground lease, the Hawks built a 90,000-square-foot practice facility, with 30,000 square feet dedicated to an Emory sports medicine facility, which the Hawks lease to the university.

Emory’s entire sports-medicine division operates within this facility, with the most advanced technology in preventative and rehabilitative treatment and sports performance training. Emory doctors can see their patients at the facility, and in conjunction with the Hawks, they will host events to engage the local community. At the end of the lease, the facilities will revert to Emory. This $50 million facility opened in October 2017, with Emory providing $14 million and the Hawks providing $36 million in funding.

- Georgia Tech has a longstanding partnership with AT&T, providing lifelong learning for the company’s employees through the Online Master of Science in Computer Science. Originally a residential program, online access has allowed Georgia Tech to scale the program at an affordable price for students. More than 6,000 students enrolled worldwide.

This program paved the way for a new partnership announced in October 2017: AT&T and Accenture will each contribute $1 million to support Georgia Tech’s new online masters’ degree in analytics.

Joint venture/operating entity. Emory and Georgia Tech have each found ways to add potential value to external partners, while simultaneously supporting the advancement of their respective strategic plans and priorities.

- For example, the Emory Genetics Laboratory (EGL), a component of Emory’s Department of Human Genetics, needed a new building, however, the facility was placed low on the capital priority list. The laboratory was growing and demand for testing services increased. Mandl and Tillman worked to create a joint venture with a publicly traded company, Eurofin, a food and pharmaceutical products testing company, that saw the value in the business of genetic testing. In a short nine months, Emory forged a partnership, receiving payment for a percentage of the entity, EGL, and a new building constructed by the third party.

- Georgia Tech has long partnered with Children’s Healthcare of Atlanta (CHOA). Beyond research collaborations, these two institutions partnered to build a life science building that supports both institutions. The Roger A. and Helen B. Krone Engineered Biosystems Building houses the Children’s Pediatric Technology Center, a research partnership with Children’s Healthcare of Atlanta and Emory University. The building provides nearly 219,000 square feet of multidisciplinary research space and enhances the institute’s partnerships with Emory and CHOA. The $113 million building opened in 2015 and was made possible because of a partnership between the institute, the Georgia Tech Foundation, and the state of Georgia. State appropriations provided $64 million for the project. Georgia Tech provided $15 million in institute funds, and private funding raised another $34 million.

Partnering for Mutual Benefit

In addition to identifying physical and program assets that could be leveraged with other outside ventures, Georgia Tech and Emory University have a history of working together.

For example, more than 15 years ago, the two universities established EmTech, at that time a biotechnology business incubation initiative to provide infrastructure for biotech startups. EmTech eventually evolved into the partnership framework that incorporates the state-of-the-art library services center.

Untapped opportunity. There were compelling reasons for the institutions to consider joining forces in the library center. Emory and Georgia Tech were each storing books on their core campus, a practice that was inefficient, especially for items that were not used frequently. Both institutions wanted to move books to a facility that would transform the respective libraries from storage facilities to a showcase for demonstrating the value of the library holdings.

At the same time, Emory owned land that was located off campus and underutilized. Opportunistically, the property happened to be conveniently located between the institutions.

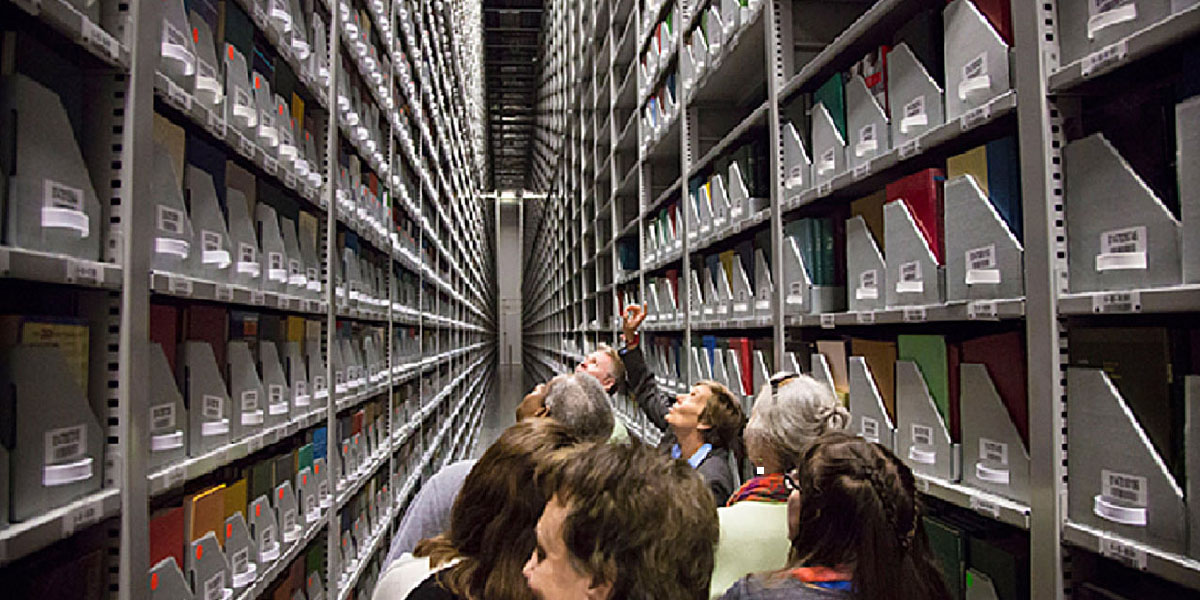

Using the partnership mechanisms forged through EmTech, Georgia Tech and Emory collaborated to build the new, shared Library Service Center on this unused land, while releasing space on each of their core campuses for more strategic purposes. In addition, only 17 percent of their respective collections overlap, meaning that, together, they could create an exceptional collection that benefits both institutions. Furthermore, by leveraging the services they can provide across both institutions, each has enhanced its ability to meet the changing needs of faculty and students, and to develop new resources and tools for use in research, teaching, and learning.

Moving forward. Each institution con-tributed equally to the $26.5 million construction of the 55,000-square-foot, secure, climate-controlled facility. While this may initially sound high for a library, by unlocking its assets on the core campus, each institution was able to produce four times the return on its investment. Emory was able to free space to showcase its rare books and manuscripts, celebrating the importance and history of literature and research. Georgia Tech is working to transform this freed space into a collaborative learning center.

Opened in 2016, the facility currently holds approximately two million volumes. The module is capable of holding four million, and the facility can accommodate another module of the same size, meaning that it may be possible for additional partners to join Emory and Georgia Tech.

By working together to establish the library center, both institutions now have access to a broader range of library materials, stored in optimal physical conditions and at a lower cost. Stakeholders have reference books and materials delivered daily to their university from the Library Service Center.

Building on Success

In January 2018, the Robert W. Woodruff Foundation pledged $400 million to Emory to find new cures for disease, develop innovative patient care models, and improve lives, while enhancing the health of individuals in need. This gift, the largest ever received by Emory, will be used to build two new facilities.

- The Winship Cancer Institute Tower in midtown will provide needed infusion facilities; operating rooms; clinical examination rooms; and spaces for rehabilitation, imaging technology, and clinical research capacity.

- The new Health Sciences Research Building, a laboratory-focused facility, on Emory’s Druid Hills campus will house faculty and staff who are charged with developing a pipeline of cures, interventions, and prevention methods, all aimed at improving patients’ health. In continuing partnership with Children’s Healthcare of Atlanta, Emory researchers in the new building also will investigate childhood diseases.

For Georgia Tech, a $30 million commitment from The Kendeda Fund, a leading philanthropic investor in civic and environmental programs in the Atlanta area, offered an opportunity to partner on a shared goal—the creation of a living-learning laboratory for hands-on educational and research opportunities and advancing sustainability in Atlanta’s community. The facility is expected to achieve Living Building Challenge 3.1 certification, with the goal of net-positive energy and water consumption, putting it on track to be the most environmentally advanced education and research building ever constructed in the Southeast.

Georgia Tech and The Kendeda Fund are targeting 2019 for occupancy. Likewise, Emory received a $500,000 grant from The Kendeda Fund, to launch a $1.5 million Sustainability Revolving Fund, a self-replenishing program that will fund capital-intensive energy and water efficiency projects across campus.

Investments by The Kendeda Fund in both these institutions demonstrate the kind of ongoing partnerships with the Atlanta community that will allow Georgia Tech and Emory University to continue mining needed support and to maintain a keen awareness of their own institution’s hidden assets.

CHRISTOPHER AUGOSTINI is executive vice president for business and administration, Emory University, Atlanta; ERIN GORE is executive vice president and national manager, Wells Fargo Higher Education and Nonprofit Banking; and STEVE SWANT is executive vice president for administration and finance, Georgia Institute of Technology, Atlanta. Mike Mandl and Jack Tillman, co-founders of Mandl & Co., also contributed to this article.