In 2016, graduate students in the United States borrowed more than $37 billion in federal loans to finance their education. Data from the National Postsecondary Student Aid Study (NPSAS) show that debt for graduate education has steadily risen over the first 12 years of the new millennium, and the College Board’s Trends in Student Aid 2017 shows the average federal loan for graduate students has risen from $9,720 in 1997, to $17,710 in 2017.

Increasing education debt may discourage students from even considering enrollment or may motivate degree completers to seek more lucrative jobs after graduation simply to pay off loans. This essay summarizes two previously published studies and discusses the implications for graduate student debt and the future of graduate education.

Back in 2012, loans for graduate and professional education were already at a record high and have shown no signs of slowing. Over the past 25 years, the average price of graduate education has increased by about 126 percent (according to National Center for Education Statistics, 2015), with some professional program costs rising more than 300 percent, as reported in the 2011 article “Law School Economics: Ka-Ching!” published in The New York Times.

To help pay these increased costs, graduate students, overall, in 2017 borrowed more than $36.7 billion in federal loans to finance their education—up from $25.2 billion just one decade ago, after accounting for inflation, according to the College Board’s Trends in Student Aid 2017. Due to changes in federal regulations, including a rise in the interest rate to Grad PLUS loans, graduate students in the future may become increasingly dependent on private loans, with early actions by Secretary of Education Besty DeVos indicating the likelihood of additional restrictions to financial aid.

Wide disparities in graduate debt exist by discipline and type/level of program. In general, graduate students in the social and behavioral sciences accrue more debt than do their peers in the physical sciences, with traditional doctoral students borrowing the least (likely due to the higher number of graduate assistantships available).

Additional concern mounts for students in law, medicine, and other professional programs who, on average, receive few graduate assistantships and have the largest amount of educational debt across all graduate student groups. For example, with average educational debts at about $145,000 in 2012, few medical students receive grants or scholarships. Of the $2.5 billion in financial assistance received by medical students in 2005–06, 80 percent was in the form of loans, according to the article “Medical student debt: Is there a limit?” in the New England Journal of Medicine.

Indeed, program costs continue to rise, yet the recent trend to shift a larger portion of tuition and fees to the student may discourage many from pursuing an advanced degree, possibly restricting their human capital and contributions to the economy and knowledge production.

Two recent studies, The Rising Tide of Graduate Student Debt: Trends From 2008 to 2012, (Webber and Burns, 2016); and Advanced Degrees of Debt: Analyzing the Patterns and Determinants of Graduate Student Borrowing, (Belasco, Trivette, and Webber, 2014), examined the rise in graduate student educational debt over the 2000 to 2012 timespan. In this article, I seek to summarize some findings from these two studies and discuss implications that senior administrative officials may wish to consider as they plan for the future of American graduate/professional education.

Recent Findings

A few recent studies guide our understanding of the current status of graduate student debt. Using 2000 and 2008 data from the National Postsecondary Student Aid Study (NPSAS), researchers Belasco, Trivette, and Webber found that borrowing among graduate students increased in 2008 compared to similar levels in 2000. In addition, these researchers found that debt incurred varied by degree program and that some underrepresented minority groups incur more graduate debt than do their white counterparts. In particular, those individuals pursuing a law degree, medical degree, or professional doctorate in fields such as education, psychology, and others, incurred more graduate debt than students pursuing a master’s or Ph.D. degree.

Belasco and a number of other scholars in this field point out that borrowing levels have serious consequences for students’ choice of major or professional program specialty area. Research examining the consequences of graduate borrowing is fairly robust, with numerous studies identifying financial resources as an important predictor of graduate degree-related outcomes. For example:

- Graduate students who relied on their own financial resources spent more time in graduate school and were less likely to complete their degrees, Bair and Haworth reported in the article “Doctoral Student Attrition and Persistence.”

- Students without sufficient departmental funds in the form of fellowships or research assistantships were less likely to complete doctoral degrees, as reported by J. Delisle, in the 2014 policy brief The Graduate Student Debt Review, in the New America Education Policy Program, and by other researchers.

- Students in professional programs also take on high educational debt, and this is particularly true for law students. Some authors address the current status of and consequences resulting from high educational costs as a “crisis.” For example, P. Campos’s article “The Crisis of the American Law School,” (Michigan Journal of Law Reform, October 2012) notes that private law school tuition increased four-fold in real, inflation-adjusted terms between 1971 and 2011. Similarly, resident tuition at public law schools has nearly quadrupled over the past two decades.

Regardless of the reasons for the increase (e.g., small student-to-faculty ratios, large salaries for professors, expansion of administrative staffs, law school fund allocations to central university budget), students are expected to pay the rising tuition, aware that full or nearly full graduate assistantships are rare.

The two recent studies used NCES’ National Postsecondary Student Aid Study (NPSAS) to examine educational debt of graduate students. Belasco, Trivette, and Webber (2014) examined debt and changes in educational loans from 2000 to 2008; and Webber and Burns (2016) examined similar debt and changes from 2008 to 2102.

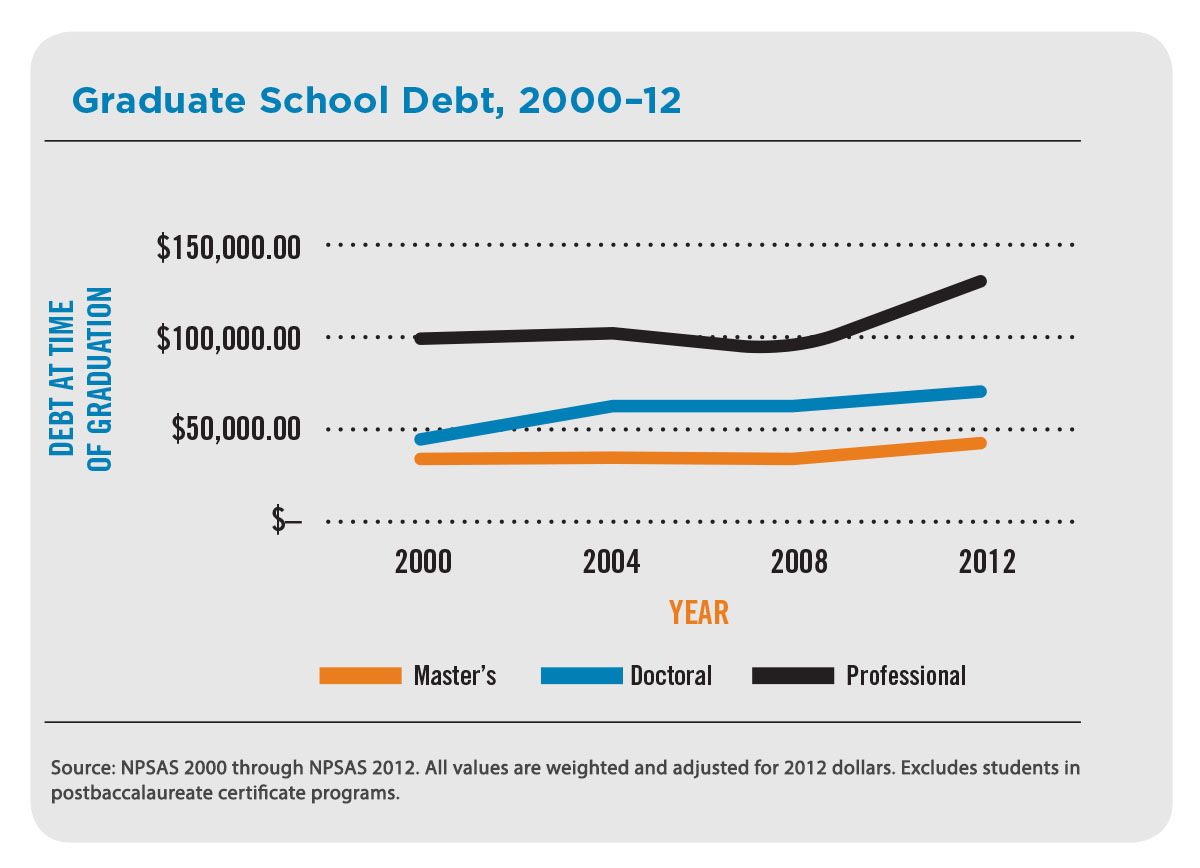

The NPSAS survey (see figure, Graduate School Debt 2000–12) samples graduate and professional students at all points in their educational programs; these two studies selected students who were completing their degrees in the year under examination. Both studies examined data that, when weighted, represented about 550,000 to 750,000 graduate/professional-level degree completers who were each attending one of about 2,000 postsecondary institutions.

Findings from the two studies show an increase in cumulative educational debt for graduate degree recipients from 2000 to 2012. Both studies found similar trends: The cumulative amount borrowed for graduate education increased over the 12-year period. From the more recent 2012 study, 61 percent of all graduate students who completed their degrees in 2012 reported borrowing for their education, compared to 51 percent in 2000.

The mean debt, based on borrowers only, increased more than $8,000 over the 12-year period, from $47,709 to $55,911 (data adjusted to 2012 values). These figures indicate that not only did the average debt rise significantly, but in the four-year period, a higher percentage of graduate students also borrowed for education.

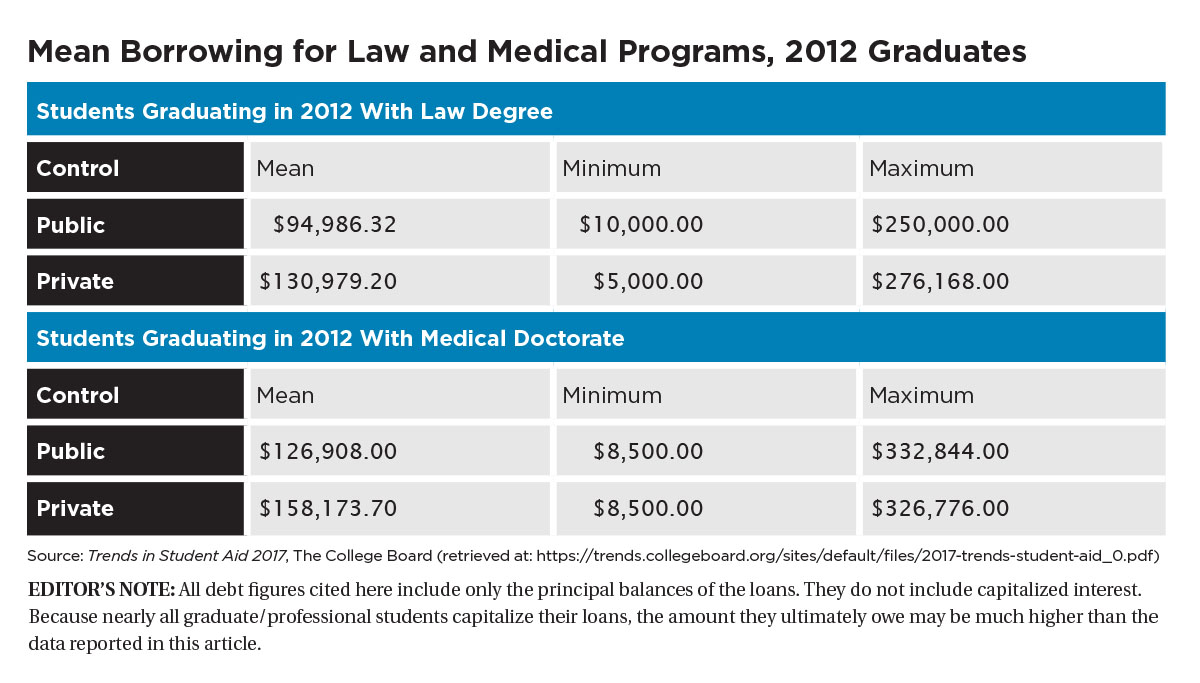

With eight of 10 professional students borrowing for their education, the table, “Mean Borrowing for Law and Medical Programs, 2012 Graduates,” also shows that professional students incur the greatest amount of debt. Webber and Burns (2016) reported that students who graduated with their doctor of medicine degree in 2012 had a mean cumulative debt of just over $144,000, and those in law had an average debt of almost $122,000. With further detail, the table shows that professional students who attend private schools report higher educational debt; the highest debt for law graduates in 2012 was more than $276,000—and more than $326,000 for those graduating with a medical degree.

Differences in graduate-level borrowing were also found by race and gender. In the Webber and Burns (2016) analysis, for example, data indicate that 15 percent more Hispanic students borrowed for their 2012 graduate education compared to those in 2008, as did nearly 11 percent more men. In 2012, just under 80 percent of all Black and Hispanic graduate students took educational loans.

The amount and percentage of students who borrowed for master’s and doctoral education increased across all sectors, but most precipitously for students in for-profit graduate programs, and it is also noteworthy that 81 percent of the 2012 degree completers in for-profit institutions borrowed for their graduate degree.

Implications for the Future

Higher education is considered an important way for individuals to advance their knowledge, careers, and subsequent long-term financial stability. Rising costs for postsecondary education and institutional reliance on tuition, due, in part, to decreased state subsidies, however, have contributed to students’ need for more educational loans.

Adding to the mix are federal policies or proposed actions that may further squeeze graduate students out of affordable financial aid. Graduate loans are no longer eligible for federally subsidized loan programs, and the unsubsidized rate for graduate students is substantially higher than rates charged to undergraduates.

Further, if students reach the aggregate maximum for total loan amount prior to degree completion (possible for students in professional programs at private institutions), they would then likely have to rely on unsubsidized loans from private sources. Currently, a small percentage of graduate and professional students rely on private loans, but it seems likely that more students in the future will seek these loans, which come with higher interest rates.

Key Implications forInstitution Leaders

The significant growth of graduate/professional student debt may have far-reaching effects. For example:

- The prospect of large student loans may simply discourage certain individuals from entering fields that cost them additional tuition and fees.

- Student debt may prohibit individuals from participating in civic and social activities that contribute to quality of life. In line with goals of formal education, these activities also facilitate the growth of human and social capital and are beneficial to the sustained growth and competitiveness of society.

- With fewer students pursuing and earning advanced degrees, the United States risks being unable to compete in the global economy. With graduate/professional-level education so important for human capital, our technologically complex and global world will continue the demand for a highly skilled workforce.

For those reasons and many more, higher education leaders have a role to play in improving the situation. Following are some caveats and goals, as well as examples of work certain institutions are doing to address the graduate student debt problem.

Officials will be challenged to consider the balance of online versus face-to-face education, ensuring high quality for all graduates. Hybrid and online programs are increasing exponentially, perhaps seen as a way to keep graduate education affordable. A number of colleges and universities are offering inexpensive, often online-only, graduate courses/degrees. For example, Georgia Institute of Technology, Atlanta, has partnered with Udacity and AT&T to offer the first online Master of Science in Computer Science degree from an accredited university. Students can earn the degree exclusively through the massive open online course (MOOC) format and at a fraction of the normal cost—approximately $7,000 for this degree. Fall 2017 enrollment in the program included nearly 6,000 students.

Institution officials responsible for graduate education are prompted to gauge future societal needs and be strategic in their decisions to add new programs, while at the same time concentrating on areas where there is high need and value. For example, programs such as robotics, cybersecurity, data sciences, biomedical engineering, and environmental sustainability likely will yield more attention and require more graduate-level training as we move forward.

The rapid increases in technology and our capacity to store and analyze large volumes of data have ushered in graduate degrees in data analytics and data science. Many of these programs are at the master’s level and seek to blend concepts and needs from business, computer science, technology, and education. Forbes’ recent list of institutions offering the top master’s degrees in data science includes Carnegie Mellon University, Pittsburgh; the University of California Berkeley; and Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Cambridge.

Graduate deans and other senior institution officials may also wish to closely monitor student success, graduate employment rates, and student loan default to inform institutional strategic planning and future policy on the relationship between degree completion, educational loans, and successful transition into the workforce after graduate degree completion. Co-op and internship programs are great opportunities for students to receive hands-on training in their field of study, funding support through pay and/or tuition remission, and networking for possible employment after graduation.

Student default rates are a fairly common point of discussion for institutions as related to undergraduate students, but less often considered for graduate students. Georgia State University, Atlanta, has become well-known for its proactive advising system that has dramatically reduced dropout rates and increased graduation numbers. While GSU’s program focuses on undergraduates, the same lessons can apply to graduate and professional students.

Another new development is the use of text messages to incoming students to help prevent summer melt. University of Virginia Assistant Professor Ben Castleman is doing interesting projects with text messages, with that goal in mind. His work with the Nudge4 Lab (http://nudge4.org/), currently in the development phase, includes targeting students who exhibit risk factors that might inhibit course completion and graduation.

Additionally, some graduate programs have annual proactive team discussions among faculty to gauge graduate student progress. And, some doctoral programs have mid-program exams that assess student acquisition of key concepts for subsequent program success.

Senior administrative officials may also wish to consider current and future policies on sources of graduate program funding. Institutions are doing this—community/industry partnerships, industry partners that support research parks/research, and so forth. Should graduate programs be less reliant on tuition as a source of funding and, instead, generate more program funds through extramural research or community/industry partnerships? Research grants captured by faculty peers in the sciences and corporate partnerships established by peers in business schools enable a higher proportion of program costs to be paid through these sources, which then diminishes the reliance on tuition.

Findings with regard to graduate debt being incurred more often by underrepresented groups contradicts the larger goal to encourage and expand higher education’s access to a broader diversity of students. Underrepresented minority students (Black/African American, Native American, Native Hawaiian, and Hispanic) are more likely to borrow than white peers (with NPSAS data showing a 15 percent increase in the amount of borrowing for Hispanic graduate students from 2008 to 2012).

Consider pros and cons of part-time study. Especially at the graduate level, individuals may wish to enroll part time while maintaining employment. Part-time students borrow less than full-time peers, but that practice may lead to unintended consequences. Part-time enrollment often extends the time to degree, which may hinder degree completion, especially for graduate students who may be more likely to experience family or other life events.

Because their overall average lifetime salaries are the highest, perhaps it is not surprising that professional students take on the larger amounts of educational debt. However, rising debt levels may now be unmanageable even with these higher earnings. Graduates of professional degree programs in 2012 reported a mean cumulative debt of more than $109,000, with medical students who took on loans reporting debt of just over $143,000, and law students at just under $124,000. Graduate students in private and for-profit institutions typically take on substantially larger loans. These high levels of cumulative debt may discourage future students from pursuing certain occupations, and/or may encourage graduates to choose specialties with even higher salaries primarily because students are concerned about how they will pay off their educational loans.

Several studies, including E. Field, Educational Debt Burden and Career Choice: Evidence from a Financial Aid Experiment at NYU Law School, (American Economic Journal, 2009) and J. Rothstein and E. Rouse, Constrained After College: Student Loans and Early Career Occupational Choices, (Journal of Public Economics, 2011), have revealed that high debt levels reduce the probability that graduates pursue public interest jobs.

Public service jobs often focus on the needs of underserved citizens, perhaps in geographically remote areas of the country. For example, it’s been reported that some medical students with high debt are less likely to choose specialties that have a long training program or to become general practitioners in poor communities.

To counter such trends, we could use more innovations like California’s EnCorps Program (encorps.org). Launched in 2007, this program offers educational fellowships to veterans and STEM retirees who wish to launch a second career as teachers.

In addition, graduate program officials may also wish to examine faculty member productivity to determine costs for graduate-level instruction. All items that contribute to the graduate program’s budget should be accountable, including faculty and professional staff salaries, costs for facilities, and external funding acquired through research grants and business partnerships.

Especially in professional programs, institution officials should also work to provide as much institutional funding for graduate teaching and research assistantships as possible. Following the model already in place for traditional Ph.D. students, more numerous graduate assistantships as well as those with a higher dollar value for professional students should be considered. Perhaps these additional assistantships can focus on research with a faculty mentor or be offered as internships in law or health clinics, where hands-on practice would be invaluable. More graduate assistantships, particularly for professional students, may indirectly encourage graduates to seek post-degree employment in positions that may pay less (at least initially) but provide needed assistance to many individuals who require such services.

Additional incentives for debt forgiveness may also encourage more graduate degree completers to enter the public or civil service sectors, and institutional analyses to monitor increases in tuition, as well as the rise in fees, are particularly important for those students who may have an assistantship that covers tuition but not the additional fees. Although Grad Plus loans are high on the administration’s chopping block, these loans are eligible for forgiveness after the graduate has worked in public-service jobs for 10 years and has made 10 years’ worth of on-time payments on his/her loan balances.

Given the importance of filling the pipeline with future professionals in so many critical fields—information technology, data analytics, education, and health and medicine—higher education administrators are key in making sure that graduate and professional students can clear the debt barrier that lies between them and their sought-after degrees.

KAREN L. WEBBER is associate professor, Institute of Higher Education, at the University of Georgia, Athens. RACHEL BURNS, a doctoral candidate in the Institute of Higher Education at the University of Georgia, assisted in the review of this essay, the underlying work for which was partially funded through AIR/Access grant RG-1601.