For the past three academic years, colleges and universities in the state of Tennessee have received funding based more on how many students completed college or completed courses than on how many students enrolled. As the first state to shift 100 percent of its higher education funding to a formula based on performance, Tennessee is blazing a trail that many states have considered following.

For the past three academic years, colleges and universities in the state of Tennessee have received funding based more on how many students completed college or completed courses than on how many students enrolled. As the first state to shift 100 percent of its higher education funding to a formula based on performance, Tennessee is blazing a trail that many states have considered following.

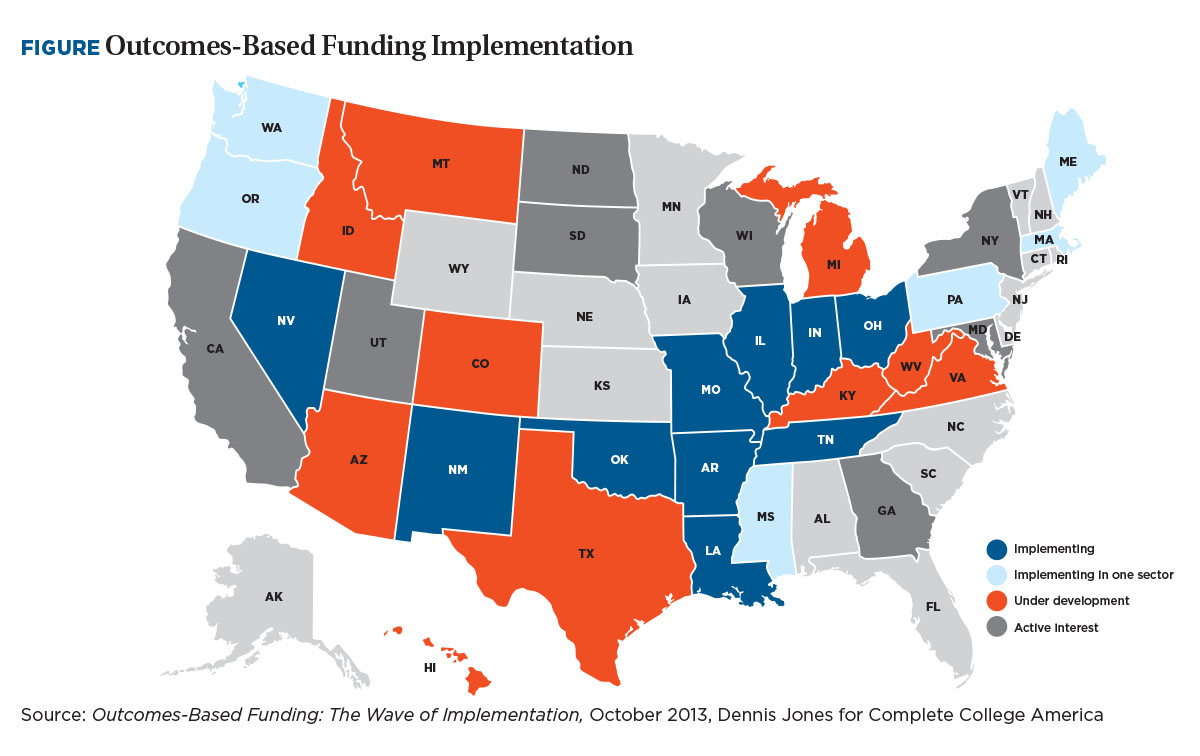

According to a recent study by Complete College America, nearly one third of states have adopted at least some performance-based funding for higher education, and most of them are aiming to base at least 25 percent of funding on outcomes, in the near future.

Performance-based funding ties governmental funding to predefined performance measures, such as student retention, graduation rates, and employment levels. With tightened state budgets, public institutions have encountered increased scrutiny from state legislatures responding to concerns about the rising cost of higher education.

As states look to improve higher education outcomes by adopting performance management metrics, debate surrounds the effectiveness of the methodology of dictating funding based on performance measures. “Providing incentives for institutions to enroll, retain, and graduate students is important,” says Joni Finney, director of the Institute for Research on Higher Education at the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia. “There is really no one model for performance-based funding, and states are clearly in an experimental phase in adapting such approaches. Research that either declares victory or defeat for performance-based funding is neither helpful nor constructive at this point. Instead, clearly documenting and understanding the various models of performance funding is an important first step toward better research.”

As increasing numbers of states move toward an outcome-based funding model (see figure), higher education leaders on both the financial and academic sides must understand the potential for change and begin to position their institutions to adapt to changing funding models and increased scrutiny of tuition policy and institution performance. Here’s a look at how some states have made their decisions and how the results are affecting higher education institutions so far.

Pinpointing Metrics

In Tennessee, where a performance-based funding formula went into effect in 2011–12, higher education leaders worked together to build the model. “We gathered campus leaders and directly asked presidents about what should be included,” says Russ Deaton, associate executive director for finance and administration for the Tennessee Higher Education Commission. “Campuses were involved every step of the way, and they seem to feel a significant level of ownership because they assisted in the development of the system.”

The Tennessee system measures different outcomes in the two-year and four-year institutions. The university model measures the number of bachelor’s and master’s degrees awarded as well as the level of research expenditures. The community college model measures the number of degrees and certificates produced, as well as the number of workforce development hours completed and student remediation successes. “There is no graduation-rate measurement in the community college model,” Deaton says. “We were sensitive to not creating a structure that would reduce access. The easiest way to improve graduation rates is to deny access on the front end, and we didn’t want to do that.”

The discussion of which outcomes to measure and how to do it in a fair and equitable way is not an easy one, especially with so many states still struggling with postrecession budget cuts. In 2013, the Washington state legislature asked public baccalaureate institutions to develop an approach to performance funding that the state could support, says Jane Sherman, vice provost for academic policy and evaluation at Washington State University (WSU).

The proposal was provided to the legislature at the beginning of the session, but no action has been taken. While there is “lots of interest” on the part of the legislature in a performance-based funding model for higher education, there is “no agreement on what, how, when, or even why,” Sherman says. “It’s not clear what, if anything, the legislature intends next.”

While the funding formula for four-year institutions in Washington state has not yet changed, 1 percent of state funding for community and technical colleges is allocated based on performance, and has been since 2007. But the state legislature didn’t make that decision. Instead, the nine-member, governor-appointed State Board for Community and Technical Colleges (SBCTC) initiated the performance-based funding system, known as the Student Achievement Initiative.

“The goal was to shift funding from being based strictly on enrollments, to also being based on student performance,” says David Prince, policy research director, at the Washington SBCTC. “The initiative grew from SBCTC-led research that identified the ‘tipping point,’ the level of education that means the difference between struggling in a minimum-wage job and having a job that leads to a better life. The initiative was designed to help advance students from one educational momentum point to the next, until the students reach and even exceed the tipping point.”

The Student Achievement Initiative awards colleges points and funding when students reach key academic milestones that lead to certificates and degrees, such as completing a certain number of credits. To determine metrics, SBCTC used a systemwide planning group with chief instruction, student services, business officers, faculty, researchers, and representatives from every other key constituency within the system. This group provided technical advice and input to the task force and conveyed information back throughout the system to college peers.

Preparing for Change

Even before Tennessee switched to basing all higher education funding on performance metrics, about 5 percent of the state’s funding for higher education was based on outcomes. “So it wasn’t new to us,” says David Collins, vice president for finance and administration, East Tennessee State University (ETSU), Johnson City. “But we wanted to make sure the new formula was fair in what it was measuring.”

For instance, many ETSU students are first-generation college students or are working adults, who typically take longer than four years to graduate. There was some concern on campus that an across-the-board focus on graduating students within four years would penalize colleges that serve those populations. However, Collins says leaders on his campus have been pleased that the final funding formula includes “lots of progress outcomes, such as students getting to 24, 48, and 72 hours, not just graduation,” he says. “It also lets each institution weight certain areas differently, such as research.”

While different student populations seem to be considered in the Tennessee funding formula, Collins says a drawback is that all fields of study are rewarded equally. “You get rewarded the same for producing a Ph.D. in biochemistry as you do for producing a Ph.D. in English or history, and the formula doesn’t take into account the varying costs,” he says. “Health sciences fields are much more expensive to offer than liberal arts.”

In the state of Washington, two-year colleges were united in supporting the research behind performance-based funding, Prince says, but “many colleges initially felt hesitant for the uncertainty that performance funding could create for them.”

Among Washington’s four-year universities, where performance-based funding has not yet been established, leaders are also hesitant about whether the specific metrics chosen will be the right ones. “Most states are asking their baccalaureate institutions for higher retention and graduation rates, fewer enrolled FTEs per degree produced, and more research funding,” says WSU’s Sherman. “Those aren’t our problems; Washington is already near the top on those measures. Where we lag most is in the participation rate of our population in baccalaureate and graduate education, and we aren’t confident that performance funding can be readily applied to that metric. We have a concern that policy makers might be inclined to solve someone else’s problems by adopting a system similar to that of a state with different challenges.”

In addition, recent budget cuts make campus leaders cringe to think about more potential losses from failing to meet performance standards. “Basically, our level of state funding dropped so precipitously during the recession that we have difficulty contemplating any performance-funding structure that might put more of it at risk,” Sherman says. “And we are not confident that the legislature could or would find new money to support performance funding.”

Seeing Results

As states build experience with performance-based funding, they are beginning to see results.

- Shifting focus. In Washington state’s community and technical colleges, the past several years of tying some funds to performance have helped shift the focus from enrollment only to education outcomes, Prince says. “The initiative has also served the system well in accounting for what happens to students during the year,” he continues. “There is a greater focus on completions in the new system through the funding distribution, which aligns with our state’s commitment to the national Completion Agenda [an initiative sponsored by the College Board, with several collaborating partners].”

- Tracking progress. In addition, the point system that measures community and technical colleges’ outcomes in Washington state has “become a common language for describing student progress within the community and technical college system,” Prince says. “Colleges and outside funding sources are using the points to measure and track the results of their student success practices.” The Student Achievement Initiative provides to the colleges quarterly data on progress and retention of their students. Colleges can track student progress toward these achievement points each quarter, providing immediate feedback and opportunities for intervention strategies. In 2013, the Washington legislature provided $5 million a year in new funding for the Student Achievement Initiative.

- Serving students. In Tennessee, colleges and universities are “getting very creative in determining new ways to serve students,” Deaton says. “They were already trying, but it does make a difference when you bring in financial implications. We’re seeing a lot of creative energy being unleashed by campuses, as they realize it’s not just about getting students in the door anymore.” For instance, institutions are rethinking advising and how to serve students who are showing signs that they need help, Deaton adds.

At ETSU, for instance, academic leaders are “beefing up” advising programs and implementing more tutoring opportunities, Collins says. The university is also using online programs like DegreeWorks to help students track their progress toward their degrees, with access to an up-to-date list of courses taken and courses needed to help them plan for upcoming semesters and complete their degrees on time.

Similar changes are beginning to take shape in Ohio. At the Ohio State University, Columbus, leaders are looking at their advising systems and at scheduling classes at appropriate times, such as offering late-afternoon and evening classes to accommodate working students, says Herbert Asher, senior vice president for government affairs.

In addition, every academic department at Ohio State has developed and publicized a “pathway” that would allow students to earn a degree in three years. “We’re looking at how students are spending their senior years in high school and offering a Maymester and other opportunities for students to earn credits quickly,” Asher says. “The funding formula creates incentives for universities to take steps that really aren’t that expensive but are very consequential in helping students succeed.”

Weighing the Risks

While some schools are making changes to boost student outcomes, Finney says it is too early to know how institutions will change in the long term in response to performance-based funding. “Strong state-level data systems are necessary to determine changes in performance and to make adjustments accordingly,” she says. “States vary in terms of the sophistication of their student unit record systems. This must be carefully aligned with the outcomes they hope that institutions will strive for.”

“Any financial policy involves a series of trade-offs,” says Tennessee’s Deaton. While he and other state education leaders believe the positives of performance-based funding “far outweigh the negatives,” he also says “until the model is road tested, you don’t know for sure how it will work out.”

- Funding challenges. While progress has been reported among schools working harder to ensure student success, the Tennessee formula is still not fully funded, in the wake of state budget crunches. “The funding remains a challenge, and if you have increased outcomes and they are not rewarded appropriately, that’s a problem,” Collins says. “For example, if an employer has a salary incentive plan and then doesn’t fund the incentives, it has difficulties continuing to get people to do what it wants them to do.”

- Competing priorities. In addition to funding issues, states that pursue performance-based funding may risk creating an imbalance of priorities. For example, the ultimate goal for most states is to serve more students effectively and direct resources to institutions that place a high priority on serving those who need to be served and that do so successfully. But aside from these outcomes, “there are many other outcomes of higher education that states care about, such as economic development and research,” Finney says.

“For research, in particular, there are already incentives in place, from states and the federal government, for strong performance, such as reduced teaching loads at research universities, direct grants to institutions’ research, or strong economic development. The performance-based model should focus, in my view, on the areas of greatest need in higher education rather than further incentivizing the strengths.”

- A partial solution. Finally, while performance-based funding may help states reach some of their goals for increasing educational attainment, it should not be viewed as a complete solution. “Performance funding only addresses how states allocate funds to institutions; it doesn’t address the larger higher education finance picture that influences performance, such as policies for state financial aid and tuition,” Finney says. “These policies are interconnected, and addressing one while ignoring the others is not likely to result in higher educational attainment.”

States must provide the public with policies in finance, governance, and accountability that will together have an impact on performance. “Trying to achieve these goals primarily, or only, through performance funding is not likely to produce the number of educated citizens needed by our economy or society,” Finney says.

NANCY MANN JACKSON, Huntsville, Alabama, covers higher education business issues for Business Officer.