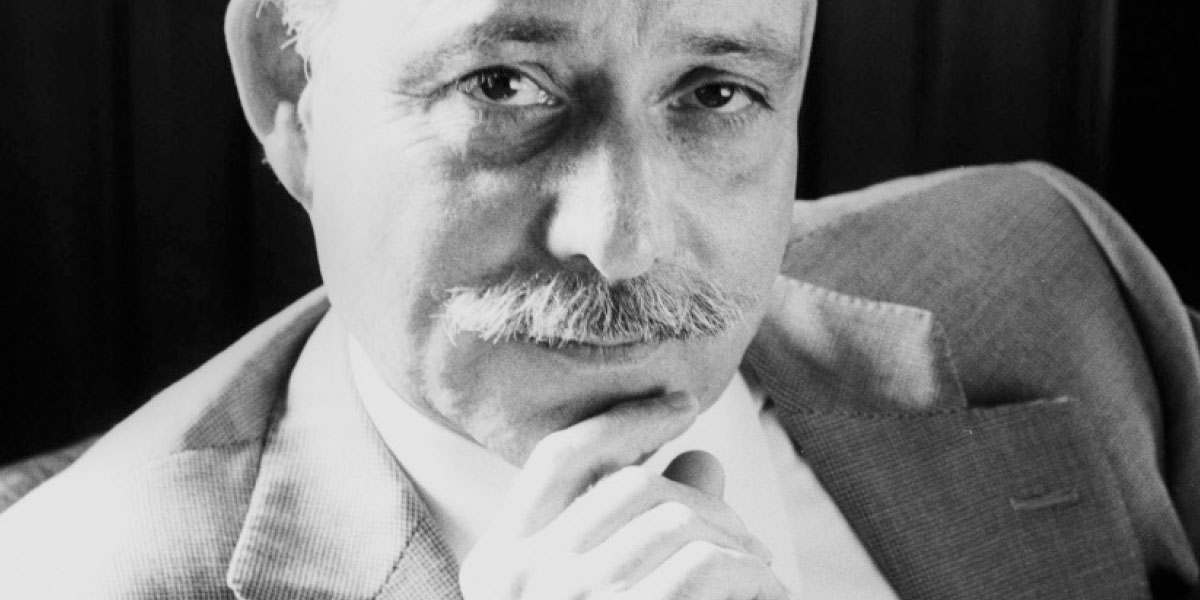

JEREMY RIFKIN is president of the Foundation on Economic Trends, and is the bestselling author of 19 books on the impact of scientific and technological changes on the economy, the workforce, society, and the environment. An adviser to the European Union for the past decade, Rifkin is the principal architect of the EU’s long-term economic sustainability plan to address the third industrial revolution, the topic of his latest book, The Third Industrial Revolution: How Lateral Power Is Transforming Energy, the Economy, and the World (Palgrave Macmillan, 2011). jrifkin@foet.org

The world is on the cusp of a third industrial revolution. We’ve got the convergence of new energy and communication tools (green energy and the Internet), earlier combinations of which have been the bases for the first industrial revolution (with steam power and the printing press) and the second one (with fossil fuels and information technology). How we handle this third revolution has great consequences for humanity, and our worldwide education system is a lynchpin in getting it right. The framework that is emerging is distributive, collaborative, and laterally scaled. It means education has to be distributed in that same way.

History Lessons

Two events in the past five years foreshadow the endgame for the second industrial revolution, which is based on fossil fuels and the technologies and institutional arrangements embedded in those energies.

The first, in July 2008, was pivotal: Oil hit $147 dollars a barrel—a record peak—and all the prices in the supply chain went through the roof. That’s because everything is made out of oil: fertilizers, pesticides, construction material, most of our pharmaceutical products, synthetic fiber, power, light. When we got to that point, people slowed down their purchasing considerably, and the economy just tanked. It literally shut down. That was actually the economic earthquake. The collapse of the financial markets 60 days later was the aftershock.

We now know in the business community that this is as far as we can globalize the world based on the second industrial revolution schema. Once oil gets into the zone of $125 to $150 a barrel, everything shuts down every time. I’m suggesting these are somewhat predictable four-, five-, and six-year cycles of growth and shutdown. And, there’s no way to get through that wall.

The other major problem relates to the climate-change talks in Copenhagen in 2009, when 192 heads of state showed up and couldn’t close the deal. Meanwhile, we have massive amounts of CO2, methane, and nitrous oxide in the atmosphere. The 2007 United Nations panel on climate change reported that the middle scenario would mean about a 3-degree Celsius temperature rise in this century. That takes us back to the Pliocene era—three million years ago—to a completely different ecosystem. [While this essay was being written, a reporting station in Hawaii registered the highest level of CO2 in human history, at 400 parts per million.]

What makes climate change so terrifying is that it changes the planet’s water cycle and all the related ecosystems that developed over eons. For every 1 degree of temperature increase, the atmosphere absorbs 7 percent more precipitation from the ground. In one tiny moment of evolutionary history, everything changes. We get more bitter snows and prolonged winters, more dramatic spring floods and summer droughts, more intense hurricanes, tornadoes—and even tsunamis. When people say it’s getting colder, not hotter, they just don’t get it. Our ecosystems are totally destabilized; virtually all predictive models say we are in real-time extinction.

To put that in perspective, we’ve had five extinction events in 450 million years. Wipeouts—and they came quickly. Each time, it took about 10 million years to recover. Models indicate we’re in a sixth extinction event, with some projections indicating a 70 percent wipeout by the end of the century. That just takes my breath away. We’re in a biosphere; we’re all interdependent; and we’re just not dealing with the enormity of it.

A Revolutionary Response

We obviously need a new economic vision that makes sense, is compelling, and can move quickly and practically in the emerging countries as well as the industrialized countries. If we have any hope for this, we have to be off carbon, except for some basic industrial uses, by 2030. The European Union (EU) now has a formal third industrial revolution plan based on a five-pillar infrastructure, starting with achieving 20 percent renewable energy by 2020.

The U.N., China, and a few others are seriously considering something similar. The outliers are the United States and Canada, with a few regional exceptions, because the energy lobby is so powerful. In Europe, more networked governance, along with public financing of elections, limits the interests of major energy companies.

But, if the United States and Canada do get locked into these old fossil fuel energies, we’re locked in for 30 years. By that time, we would be absolutely a second-tier country.

What we’ve started in the EU is based on understanding that new energy sources facilitate more complex civilization that integrates more people into bigger units with differentiated labor skills. This then requires communication that is agile enough to coordinate and manage those regimes.

In the early 19th century, for example, manual printing gave way to steam-powered presses, which meant that we could mass-produce huge volumes of material very cheaply. We introduced public schools in Europe and America and created a workforce with reading and communication skills to manage a complex coal-powered and rail-run industrial revolution.

Similarly, in the 20th century, electricity brought us centralized communication—with the telephone, radio, and television—and powered auto assembly lines, which brought about mass production of automobiles, the need for an interstate highway system, and the creation of suburbs. It all came together as an integrated infrastructure.

What’s interesting about the third revolution is the distribution of power. Whereas fossil fuels are located in only a few places and require big military and geopolitical investments—and massive capital—what is converging now in Europe are energies—sun, wind, a hot geothermal core, ocean tides and waves—that are distributed and organized collaboratively and scaled laterally. We have to be able to finance both the communication and the energy regimes and then integrate factories, logistics, and transport into a general-purpose technology platform that drives an economic revolution.

Education to the Rescue

This kind of technological innovation is within our grasp, but the key to a positive future is as much operational innovation as it is technological. And since education is the primary means for reinventing how we do things in our society, we have to change the entire learning model. It’s a consciousness shift as much as it is a vocational shift.

Our current model follows the centralized factory model. The teacher makes assignments; the kids have a certain amount of time to produce; they memorize and spit back answers. They’re taught that knowledge is power. If they share information, it’s cheating. And, they’re made to believe that knowledge is something you possess as an autonomous agent pursuing your own self-interest. It’s not something you share to create common meanings.

It’s a complete disconnect for kids growing up with the Internet, and we have to move to a collaborative, peer-to-peer approach. To apply those principles at all levels, we can:

- Break open the classroom. Instead of maintaining a siloed place, we open up to virtual space with Skype and with global classrooms that allow students to interact across cultures, narratives, and value systems, so we can have a rich diversity of experience within each cohort group. It’s exciting when students start to think of themselves as more of a human family.

- Emphasize service learning. Millions of young people participate in service learning, which is terrific because if learning is a shared experience—with the purpose of creating a sense of common social capital and fostering the realization that learning is something we do between and among people—it’s a transcendent part of what we do. So, if we’re learning about environmental science, learn it in an arboretum. If we’re studying about societal problems of the elderly, go to a senior citizen center, engage in that environment, and then bring the experience back to your sociology class. Such pedagogy is crucial to enhancing service learning.

- Break it open in terms of disciplines. It’s absurd to be teaching each discipline in a silo, as if it were the sole truth. We have to have interdisciplinary teaching, with multiple perspectives. Let students learn in cohort groups for which the teacher serves as facilitator and guide, imparting ideas while allowing students to break into groups and be responsible for their own learning. It’s rather like the one-room classroom where the older kids taught the younger ones.

Cohort learning means that there’s a structured assignment, students each take a part of it and teach the others, and they learn that education is not merely performing for a centralized teacher. It’s actually creating shared meanings by peer-to-peer engagement, which they’re doing on the Internet every day.

While Coursera and other massive open online courses (MOOCs) are proliferating, I also see students interacting in virtual space, setting up real-time study groups, and even grading each other’s work. And they’re checking, like people do with Wikipedia, for false premises or incorrect answers. If someone puts something out there, another student might say, “No, this is not it.” It’s an amazing lateral experience.

But, this shouldn’t take place only in virtual space; let’s get them out in the community. Ultimately, education should be an empathic engagement where people can share experiences, because that’s the basics of all thinking: empathic sensibilities built into our neurocircuitry. We learn by being able to experience others as we experience ourselves.

- Balance interactive experience with focused individual thinking. Much of the virtual and group experience is external, and it generates endless communication. Every student thinks he or she “gets it” instantly, so they’re not going to go any deeper. That’s a real problem. Reducing the attention span takes a toll on mindfulness. When we try to process ideas in too many places at once, the mind simply doesn’t work that way. Mindfulness and empathy can’t grow without attention and focus. How do we reconceptualize our thinking so that we get the best of the connectivity in a laterally scaled world, but we push back and demand layer upon layer of critical thinking?

I do think we’re on the cusp of a shift of balance in terms of consciousness. For example, 13- and 14-year-olds are coming home from their sustainability classes saying, “Why are you using so much water? Why do we have two cars? What’s that hamburger doing on my plate?” The kids are connecting the dots and understanding that everything they do has an ecological footprint. Every other species, even the butterfly, affects the well-being of some other family or creature or ecosystem in one indivisible biosphere. And, they’re learning that from the stratosphere to the oceans, where geochemical living processes interact, it’s all an indivisible community.

The idea that they’re understanding the ecological footprint and developing biosphere consciousness, that’s a huge shift. Combine that with distributive, collaborative, laterally scaled education—and we have a new kind of human being. It’s one who can begin to see the human race as an extended family, our fellow creatures as part of the evolutionary family, and our planet as an indivisible biosphere community.

GLOBAL CHALLENGES

By The Numbers: Globe Trekking