Within higher education, the median long-term total debt carried by a college or university stands at $55.2 million, according to the 2014 NACUBO–Commonfund Study of Endowments. Because that debt not only represents a long-term commitment of serious financial resources but also carries risk, it has implications for future financial flexibility and institutional decisions.

The debt obligations incurred today, for example, are likely to last through several generations of institutional leaders—something today’s financial leaders must consider as they grapple with a low-interest rate environment for savings and endowments, low or no growth in net tuition revenue, and turmoil in global stock markets. At the same time, those leaders must acknowledge growing sensitivity to tuition pricing and address issues arising from deferred maintenance, even as they contemplate the new or renovated facilities needed to remain competitive in attracting students.

In short, how much debt your institution can take on—and how to best structure it—is a strategic decision of paramount importance today as well as for years to come. College and University Business Administration—the NACUBO publication commonly known as CUBA—offers guidance for making those decisions in the chapter titled “Strategic Debt Management.”

Here are excerpts from the just-released chapter of CUBA.

Not everything a college or university wants to do can be financed. For example, debt issued to finance a new athletic field is debt that may not be available for a new classroom building, residence hall, or research facility. Debt, therefore, must be tied to the institution’s strategic goals and directions.

Ambitious strategic plans tend to generate financial demands, which in turn lead to this key question: Is debt right for our institution? Before answering that question, governing boards and senior management must understand both the positive and negative implications of debt.

On the positive side, debt can enable an institution to pursue ambitions far beyond what it could achieve with just its current resources—a trade-off most business officers are willing to make. For instance, constructing a new residential facility will benefit not just current students but also future students, perhaps pointing to financing it over a longer period of time.

A well-conceived debt program broadens institutional options, affording opportunities and possibilities that may not otherwise occur. As an example, the cash flow for a project financed with gifts tends to stretch out over a long period of time. Borrowing based on today’s capacity, without including gift cash flow, would reduce the potential projects a college could finance.

Debt also imposes budgetary discipline. A college or university that funds major maintenance with debt, for example, can no longer yield to the temptation to reallocate budget lines; the debt service that enabled upgrade of the physical plant has become a fixed cost. By setting debt limits—such as limiting debt service as a percentage of its operating budget—the institution can manage expectations about how much new debt can be incurred.

Despite the benefits of issuing debt to build institutional capacity and support or enhance strategic plans, debt also has potential negative consequences. While debt service imposes discipline, it can also diminish future budget flexibility over many years. And, because debt service is a fixed cost, it may limit capacity in other ways—such as delaying plans for hiring new faculty or increasing student financial assistance. With invalid assumptions about the future, debt can also sink an institution—the ultimate downside.

Many cases of institutional bankruptcy, in fact, involve not just reduced revenues and reduced business prospects but also high levels of debt. The obligations simply proved too burdensome for the institution’s financial profile. In some cases, the institution might have survived had a high portion of its operating budget not been dedicated to debt repayment.

Credit Ratings

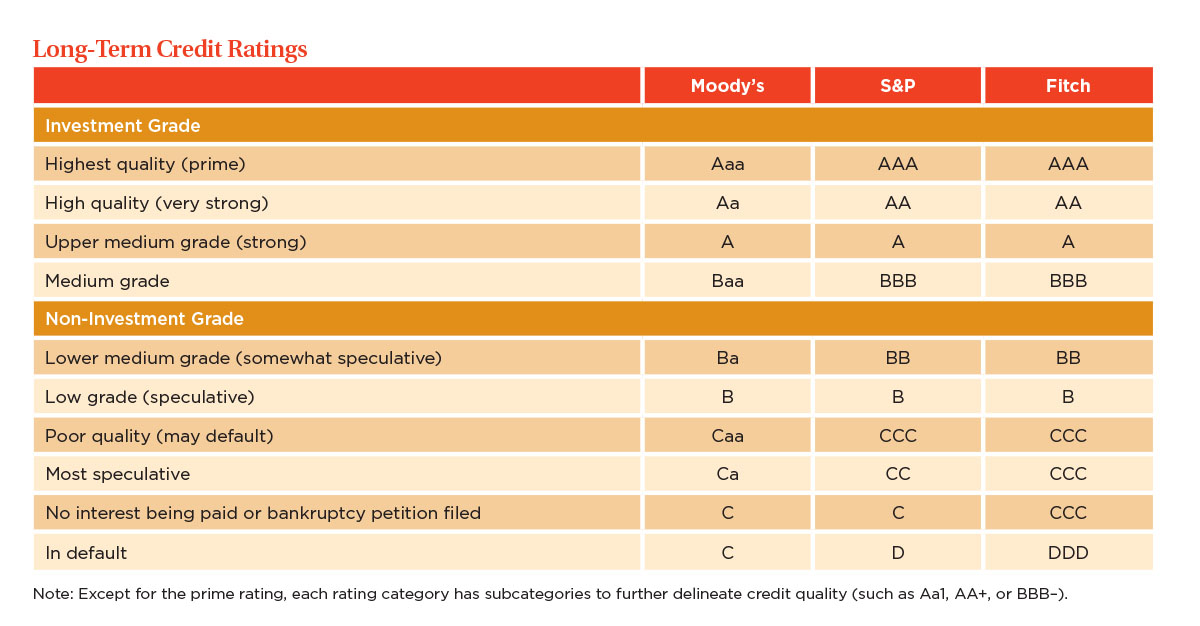

Credit ratings measure the likelihood of timely and complete repayment of principal and interest on debt. They provide a graded system by which investors can readily judge the relative investment quality of bonds.

An institution’s credit rating:

- Serves as one indicator of an institution’s overall financial strength.

- Helps determine the interest rate at which an institution can borrow, in some cases for many years.

- Helps an institution focus on assuming debt for its highest priorities; a good rating is a coveted resource that typically depends on the prudent use of debt.

- If good, [a credit rating] can better position an institution to meet unexpected emergencies by issuing debt.

Commercial banks and other lending institutions perform internal credit analyses and ratings for their own credit decisions. Other potential investors, however, have limited capacity to analyze in detail the underlying business operations, financial strength, and security structure of each bond instrument being considered. Therefore, public debt markets often depend on independent rating agencies to develop credit-rating criteria, formulate and apply credit analysis techniques, and establish and maintain published credit ratings on issuers and issues.

These services can prove particularly useful for institutions contemplating debt issuance for the first time. A bond or note issue is normally rated prior to its sale, although some issues are sold as unrated; many investors view an unrated issue as one likely to be speculative grade credit quality.

After a rated bond issue is sold, the rating agency (or agencies) selected for the rating regularly reviews the credit rating. Generally, the review happens annually, although it could be less often. The rating assigned directly affects the marketability and the yields on the initial offering of the bonds, as well as an investor’s ability to trade the security in the secondary market.

In higher education, most credit ratings are assigned to individual issues, not to issuers, of bonds. The credit ratings assigned to the issues reflect the institution’s capacity to repay a specific bond obligation given the security structure of that issue. Nonetheless, the process of analyzing the creditworthiness of the bond issue includes a comprehensive analysis of the issuer’s overall credit characteristics and resources. In many cases, the issue rating is equal to or close to the relative credit quality of the institution’s underlying creditworthiness.

The three independent rating agencies most often used in higher education are Moody’s Investors Service Inc.; Standard & Poor’s Financial Services LLC (S&P); and Fitch Ratings. They issue long-term credit ratings in two categories: investment grade and non-investment grade (also known as speculative grade).

Short-term ratings emphasize the liquidity of the institution borrowing the money and short-term cyclical elements, rather than long-term credit risk. Again, each ratings agency has a different, but comparable, series of ratings. For example, the Prime-1 rating issued by Moody’s indicates the best ability to repay short-term debt. S&P’s top rating is A-1 (obligor’s capacity to meet its financial commitment on the obligation is strong), while Fitch uses F1+ (exceptionally strong capacity of obligor to meet its financial commitment).

Short-term ratings may be issued independently from long-term ratings, although a strong correlation between the two types of ratings often exists. In many cases, for example, the long-term rating helps determine the short-term rating. …

Bonds

Colleges and universities that assume debt are often engaged in the bond market; within that market, they have historically issued more tax-exempt than taxable municipal bonds. Tax-exempt market instruments differ distinctly from taxable corporate bonds in a number of ways, including issuance volume, security structures, types of investors, and yield behavior.

A bond is a promise to repay a specified sum (principal) plus compensation (interest) to a lender for use of the lender’s money, with payments to be made on specified dates. The maturity of a bond is the date when the principal amount (par value) becomes due and payable. A bond traded at a price below its par value is a discount bond; a bond traded at a price above its par value is a premium bond.

The bond repayment terms, interest rate (coupon), and initial price define the percentage rate of compensation to bondholders (yield) during the life of the bond. Yield is usually expressed as a nominal annual rate, although actual interest payments are typically made semiannually, quarterly, or monthly.

With capital markets now automated, nearly all bonds are issued as book-entry bonds. That means they are registered with a central system, such as Depository Trust Company—a consortium of banks and brokers. Physical bond certificates are not issued in book-entry bond issuances.

Off-Balance-Sheet Financing

Since the early 2000s, higher education’s use of off-balance-sheet financing—also called nonrecourse debt—has increased. This form of debt can play a useful role, particularly in the funding of auxiliaries, where bond issues are supported by the anticipated revenues from the project, be it a residence hall, parking garage, dining facility, athletic facility that generates revenue, or research building.

Most often, the terms privatized and nonrecourse debt refer to a campus facility not owned by that campus but by a third party, and to debt used to build such a facility, which is not legally debt of that campus. The third party can be a 501(c)(3) nonprofit entity or a private sector company.

Institutions principally turn to nonrecourse debt so they can engage the skills of the private sector to develop and own, or manage, campus facilities. While nonrecourse debt is typically a more expensive form of capital compared to traditional institutional recourse debt, the private sector can often absorb project risks, such as cost overrun exposure and delivery date deadlines. Also, in many circumstances, a third party can construct a project in a more efficient and timely fashion.

Public institutions, in particular, tend to have procurement processes that lead to inordinate delays in project execution. These processes can also result in a more expensive project. Elements of risk include:

- Counterparty risk, in both the development and execution of the project.

- Association risk—the risk that a negative project will be perceived as being operated by the institution.

- Business risk, because the institution’s customers or constituents use the facility.

Student housing is the type of facility most often privatized. According to George K. Baum, an investment banking firm, more than $5 billion of nonrecourse debt for housing was issued between 1992 and 2014 at more than 300 higher education institutions.

Another key attribute of public-private partnerships is the monetization of a campus asset that generates cash flow but is not considered a “core” function of the institution. Public institutions, which have more limited options for capital renewal, and constrained state funding, have found such partnerships particularly appealing because they have the opportunity to convert a physical asset from a cash drain to a cash source. Examples include:

- The University of Kentucky signing a long-term contract for a private sector company to renovate all of its student housing, in return for future housing cash flows.

- The Board of Regents of the University System of Georgia selecting a developer/equity partner to provide on-campus student housing (a minimum of 3,000 new beds) at seven of its 31 campuses for long-term concession. The private sector firm provides funding for the new construction and bears all development costs, including program management fees.

- Ohio University agreeing to a master lease with a developer that built and owns the university’s nursing school—all off-balance-sheet financing for the institution.

- In 2012, Ohio State University signing a 50-year agreement to lease its parking operations to a private operator. The university received an upfront payment exceeding $480 million, which went into its endowment to fund student scholarships, faculty hiring, and research initiatives.

If tax-exempt bond financing is involved, off-balance-sheet financing takes the additional step of using an existing—or creating a separate—entity, typically a 501(c)(3) nonprofit foundation, to issue the debt.

An alternative form of off-balance-sheet financing has been created by Real Estate Investment Trusts (REITs), which use private sector equity to build, own, and manage student housing. Typically, the host institution leases the land for this housing to the REIT on a very long-term ground lease (50 to 60 years). The REIT bears all the project risk, so there is likely no impact on the institution’s rating.

On the other hand, this approach to student housing has several costs and concerns:

Local property taxes are usually levied because the property is privately owned. These taxes need to be included in student rents.

- The REIT owner’s cost of capital is higher than that of a tax-exempt, university-owned project.

- A REIT-financed project requires a considerably longer-term ground lease of more than 50 years.

- Rental rates for a REIT-owned project are typically not under any significant institutional control.

- The university bears the risk that the initial REIT will sell the project to a subsequent private sector owner. This means the university will probably have to deal with future owners that may not be as amenable to its concerns as the initial REIT.

Although such debt can be off the institution’s balance sheet, it can still be tied to the institution’s overall debt rating. The stronger the link between the institution and the project—in other words, the more the institution lends its credit integrity to the project—the greater the impact on the institution’s credit rating, whatever the formal financing mechanism. This relationship has both positive and negative implications.

Assume, for example, that an institution with a strong credit rating decides to issue off-balance-sheet debt. A weak link with the project will not affect the institution’s own creditworthiness but will likely result in a lower rating (and, thus, a higher cost of borrowing) for the project. Conversely, a strong link with the project will have a direct effect on the institution’s debt capacity but likely result in a higher credit rating and lower cost of borrowing.

Off-balance-sheet financing is subject to many of the same evaluation criteria as other projects. These include long-term institutional viability, demand for the project, debt service coverage from pledged revenues, construction risk, reserves for maintenance and insurance, managerial control, and the reasonableness of operating assumptions (such as occupancy rates).

In addition, the institution’s degree of oversight is an important consideration in the credit rating. When a private company is involved in the project, the rating agency will want to know the nature of the partnership (such as which party pays for contingency repairs), the institution’s experience with such arrangements, and the perception of the partnership among key constituencies (such as trustees and students).

SANDRA R. SABO, Mendota Heights, Minn., who covers higher education issues for Business Officer, wrote the introduction to this excerpt and edited the chapter, “Strategic Debt Management,” from which it is taken.

For complimentary access to the “Strategic Debt Management” chapter of College and University Business Administration (CUBA), go to the

For complimentary access to the “Strategic Debt Management” chapter of College and University Business Administration (CUBA), go to the