A year ago, college and university endowments appeared to have finally recovered from the steep losses suffered during the 2008–09 financial crisis. Stock markets around the world were rising; the U.S. economic recovery was gaining steam; and low interest rates were helping to fuel growth in stocks, bonds, and other asset classes. In this environment, the American higher education endowments that were measured by the 2014 NACUBO-Commonfund Study of Endowments (NCSE), achieved an average investment return (net of investment fees) of 15.5 percent. Improving fiscal conditions at the end of FY14 appeared to be poised to whet investors’ appetites for even greater gains.

However, in FY15, the financial recovery began to chill. The July 1, 2014, to June 30, 2015, period saw nothing but disappointing news. China’s slowing economy hurt stock investors all over the world; a major slump in oil price was a boost to consumers, but caused steep declines in commodities and energy-related investments; and in the U.S., while the employment market continued to gain steam, the Federal Reserve—which kept its federal funds rate at near zero throughout much of the Great Recession—began talking about raising interest rates, which initially hurt bond investments.

All these factors brought investors much lower returns, particularly in foreign stocks. In FY15, the MSCI ex U.S. index returned –5.3 percent, which stands in stark contrast to FY14’s gain of 23.3 percent. The U.S. stock market, as measured by the Standard and Poor’s 500 index, gained 7.4 percent. But this was a far cry from FY14’s performance of 24.6 percent.

Investment performance for college and university endowment professionals was particularly affected by the changes in the financial markets between 2014 and 2015. After rocketing to a 15.5 percent return in FY14, endowments averaged an investment gain of just 2.4 percent (net of fees) in 2015, according to the 2015 NACUBO-Commonfund Study of Endowments. The FY15 performance was the lowest return for endowments since 2012 (–0.3 percent). And continued economic troubles in the U.S. and around the world during the first half of FY16 suggest that an even lower endowment performance may be in the offing.

This overview of the 2015 NCSE results takes a look at the issues that campus endowment managers dealt with last year, and examines the myriad fiscal and economic challenges that endowment managers and other higher education leaders are facing in FY16 and beyond.

Much Lower Returns, Regardless of Size

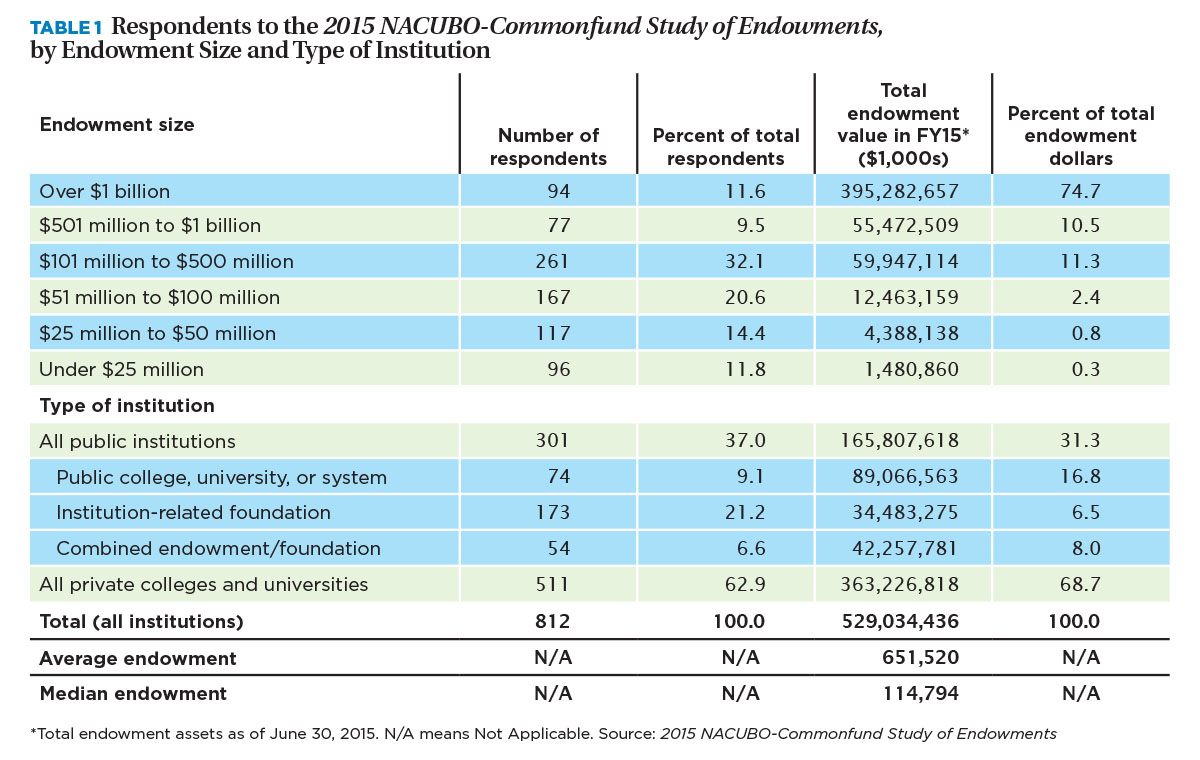

Participation in the 2015 NCSE totaled 812 U.S. colleges, universities, and affiliated foundations. Collectively, these institutions held a total of $529 billion in endowment assets as of June 30, 2015 (see Table 1). Nearly 12 percent of the participating schools had total endowment assets of $1 billion or more; these institutions accounted for almost three quarters of the total endowment dollars among the 2015 NCSE participants. The average endowment among all the participating schools was $651.5 million, while the median was $114.8 million.

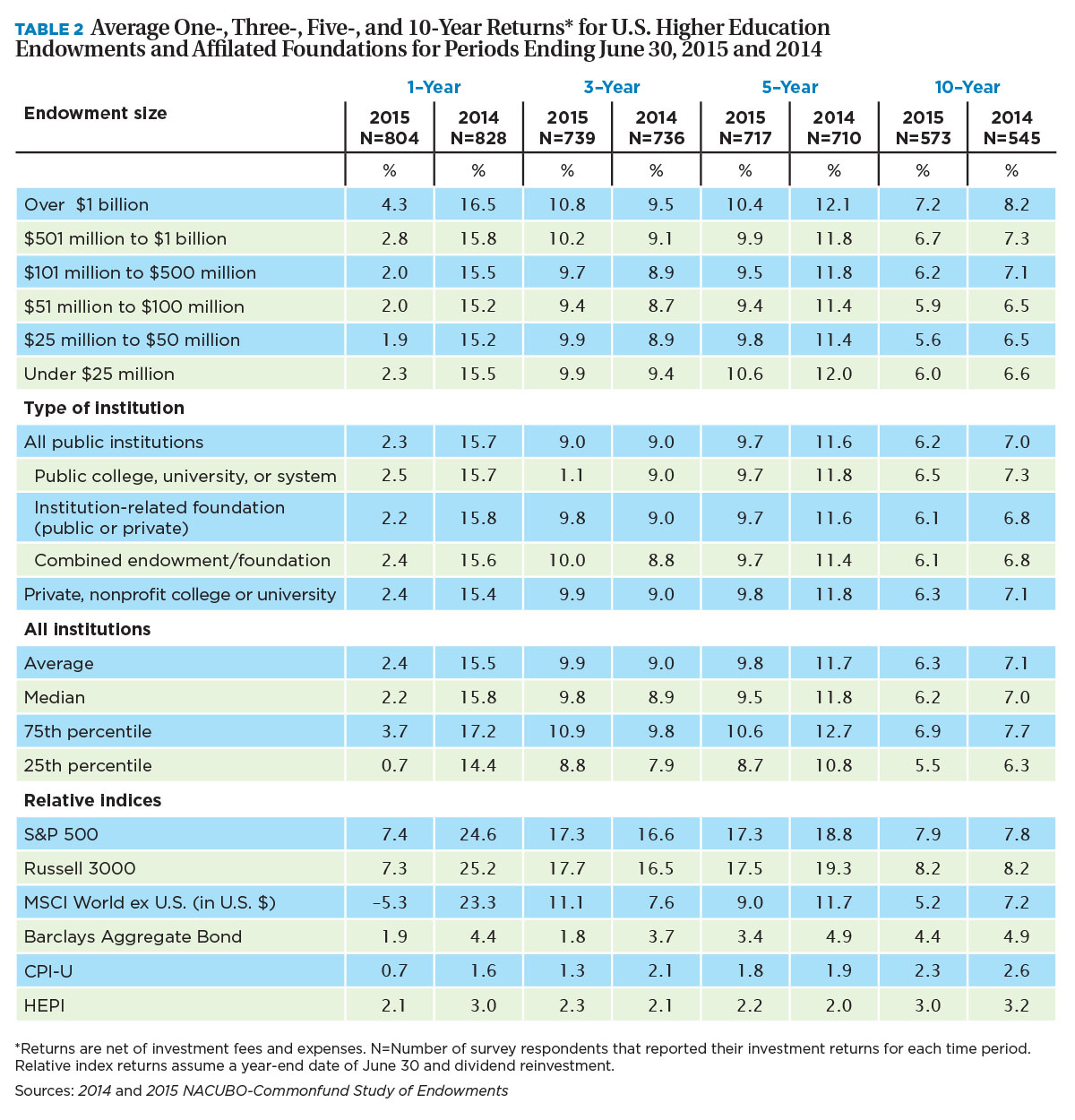

As Table 2 shows, both large- and small-endowment size categories saw substantially lower one-year average returns in FY15. The largest endow-ments reported an average FY15 gain of just 4.3 percent, compared with 16.5 percent in 2014. The lower gains among endowments valued between $501 million and $1 billion were nearly as great (2.8 percent against 15.8 percent), while schools with total endowments of under $25 million saw their average returns drop to 2.3 percent compared with 15.5 percent previously.

“This year’s lower returns reflect the continuing volatility that has been a feature of the financial markets since 2008,” says NACUBO President and CEO John Walda. “We have seen this volatility every year since 2001, a reflection of the two economic recessions and slower-than-expected recoveries we have all faced over the past 15 years.”

While the one-year returns in the NCSE garner much of the attention, returns over the past 10 years are often a much more important indicator because many endowment managers and campus chief business officers use 10-year average annual returns as a target for long-range planning purposes. As Table 2 shows, in 2015, the overall average 10-year return was 6.3 percent, down from 7.1 percent in FY14. The smallest endowments achieved an average FY15 long-term return average of only 6 percent, six-tenths of a point lower than the year prior. These average 10-year returns were much lower than most schools’ long-term targets. The median long-term return goal for FY15 was 7.5 percent.

As William F. Jarvis, executive director of the Commonfund Institute and one of the authors of the annual NCSE report, points out, the lower 10-year return for campus endowed funds is not just a one-year phenomenon. “During most of the past seven years, the majority of endowments have been unable to meet their long-term return objectives, largely due to the tough market conditions we have faced during much of that time period. If growth continues to remain below 7 percent for much longer, endowments will potentially be unable to meet their main goal of providing income for today’s students and faculty, while generating inflation-adjusted growth for future generations.”

Endowment Spending Up Sharply

Despite FY15’s lower returns, many institutions increased the amounts that they withdrew from their endowments to support student financial aid, faculty research, and other vital programs.

The share of survey participants who increased endowment withdrawals for campus-related programs grew from 74 percent in FY14 to 78 percent in FY15. (See figure in “Funds Support Students, Campuses.”) Among the schools with total endowments over $1 billion, the proportion that increased spending rose from 79 percent to 83 percent. The spending increases were substantial. The median increase in spending dollars for those who withdrew additional endowment funds was 8.8 percent. The median spending growth was 7.1 percent for the largest endowments; for the smallest, it was 12.4 percent (larger institutions have much higher dollar amounts, so any increases in spending amounts will be smaller in percentage terms for larger endowed schools than smaller ones.)

Due to the increase in spending, the endowment withdrawals as a share of total institutional operating budgets increased from 9.2 percent in FY14 to 9.7 percent in FY15; among schools with the largest endowments, withdrawal dollars constituted 16.5 percent of operating revenue in FY15.

This level of spending increases does not surprise Jarvis. “Our data show that since FY09, an average of 59 percent of NCSE participants had year-over-year increases in endowment spending, and the average of the median increases was 8.7 percent. Increases in spending from endowment have been well in excess of inflation.”

And as Walda points out, spending from endowments has been a critical component for stabilizing funding for colleges at a time when other revenue sources have declined. “Since the Great Recession, most states have cut back their appropriations for higher education,” he says. “The current flexibility institutional leaders have when administering endowed assets clearly allows for vast spending increases during market turbulence. These increases have ultimately allowed schools to preserve access to college for students, and to support cutting-edge research from faculty. Endowment funds remain a key ingredient for schools to meet their goals now and in the future.”

Asset Allocations Remained Stable

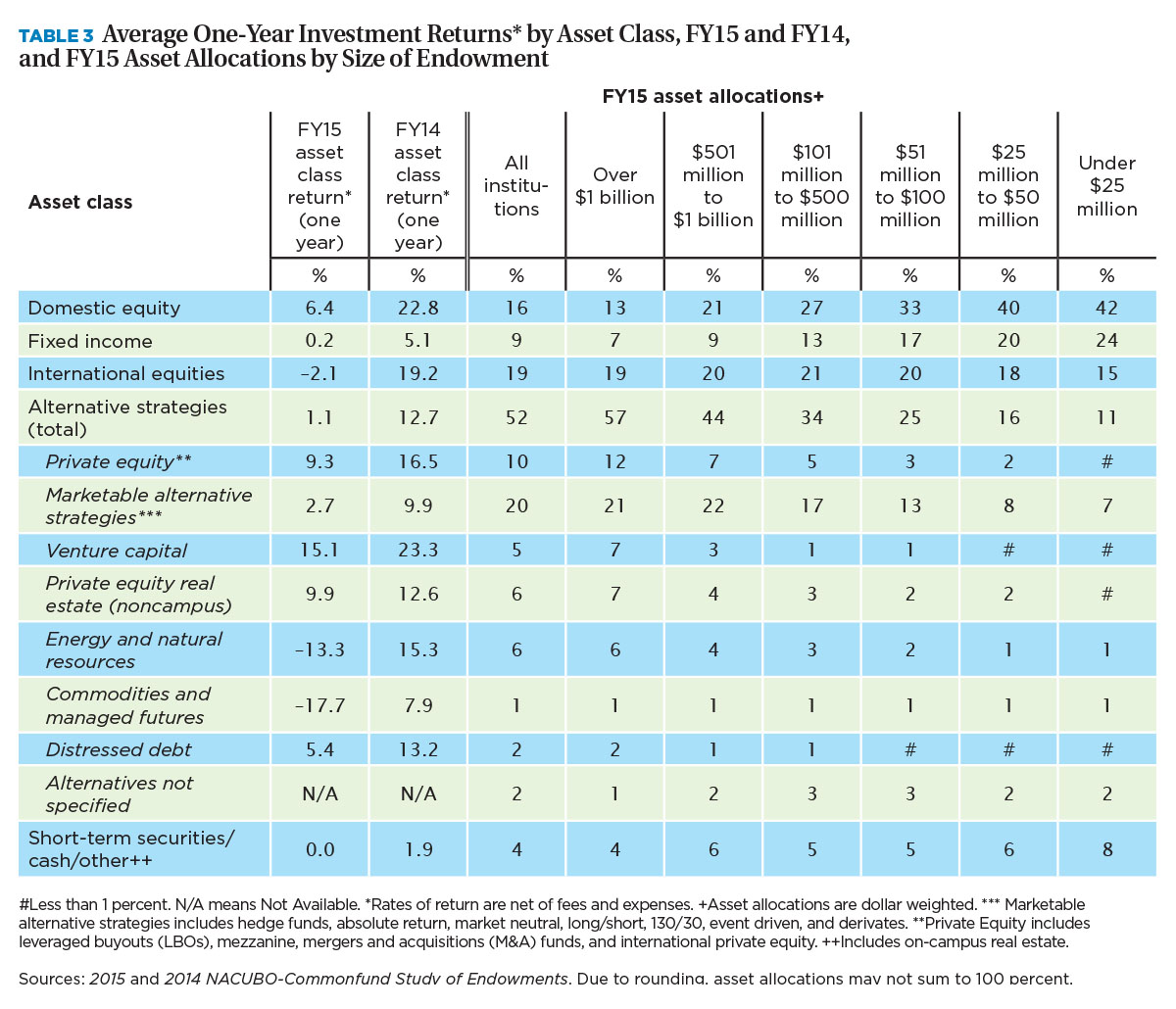

Despite raising endowment spending, investment managers kept their portfolio asset allocation strategies largely intact during the year. Between FY14 and FY15, there were only minor changes to overall asset allocations. For example, the average share of assets invested in U.S. stocks from 2014 to 2015 fell only 1 percentage point, from 17 percent to 16 percent. Investments in fixed income (foreign and U.S. bonds) and international stocks remained stable, and allocations to alternative strategies (such as hedge funds, commodities, private equities, and venture capital) grew only slightly, from 51 percent to 52 percent.

What changed radically, as Table 3 illustrates, was the performance of a number of assets in endowment portfolios. Commodities and managed futures, for example, produced a 7.9 percent return in FY14, but posted a –17.7 percent return in FY15. All asset classes had sharply lower returns in FY15 than FY14, but venture capital in endowment portfolios did manage a gain of 15.1 percent in FY15, followed by noncampus private equity real estate (9.9 percent) and private equity (9.3 percent). Schools with over $1 billion in endowed assets were more likely to benefit from the gains in venture capital. In FY15, 7 percent of the largest endowments’ assets were invested in venture capital, compared with less than 1 percent of the smallest endowments. It is likely that this difference in asset allocation accounts for the higher overall returns that the largest endowments achieved in 2015.

Fiscal Challenges Continue

While FY15’s lower-than-expected returns are disappointing, FY16 and beyond could be much worse. During the first half of the fiscal year, China devalued its currency, which sent world stock markets plunging. In addition, a continued slide in the price of oil and other commodities, combined with renewed fears of an economic slowdown in the U.S and China, have rattled investors worldwide. From July 2015 to mid-January of FY16, the S&P 500 was down nearly 10 percent and international stocks declined nearly 16 percent, according to Yahoo Finance.

Jarvis believes that the subdued economic environment could be with us for some time, and could have an impact on endowments’ efforts to support their institutions’ current needs while achieving growth for the future. “Many economists believe that lower global economic growth and lower investment returns will be with us for several years. Lower returns, if they persist and if they are combined with generous endowment spending practices, may adversely affect institutions’ ability to maintain the purchasing power of their endowments in a future environment in which economic growth and investment results may be lower than in recent years.” (For additional comments about the U.S. economy’s future, see an interview with Mark Zandi.)

Lower returns are not the only financial pressure weighing on most higher education institutions. Many schools continue to struggle in FY16, in spite of raising their endowment spending dollars. State appropriations on a per-student basis have declined 12 percent since FY04, according to the Delta Cost Project. In addition, student enrollments have been falling at a number of campuses in recent years, and are expected to continue to decline. And there is added pressure from policymakers, families, and students to freeze or cut tuition, while maintaining access and affordability for students, and to raise endowment spending even more to support financial aid programs.

As Walda points out, endowments will be a key instrument to help institutions meet these future challenges. “Especially in these tough economic times, endowments remain essential,” he says. “The fact that schools have been able to raise their endowment dollars as state support and other sources of funding have fallen—and financial markets have turned turbulent—is a testament to the endowment managers and others on campus who are doing all they can to meet the needs of students and faculty. The flexibility that the current policy affords these funds will be a key feature to protect and strengthen endowment funds for the future.”

KENNETH E. REDD is director, research and policy analysis, NACUBO.