For more than four decades, University of Kentucky Health Care (UKHC) operated in traditional silos. Both fiscally and administratively, each division or section of the Lexington-based institution had its own secretarial, finance and procurement, billing, and even human resources functions. Likewise, most divisions independently managed their respective clinics, patient scheduling, and correspondence.

This “cottage industry” arrangement worked well when UKHC ranked 85th in size among academic health-care centers, with about 24,000 discharges per year. By 2012, however, expansion had occurred with the construction of a new hospital and creation of numerous alliances and networks. Discharges topped 38,000 per year, moving UKHC up to the 32nd spot in the University Hospital Consortium, the alliance of the nation’s leading academic medical centers.

That growth—coupled with federal and state budget cuts, legislation impacting revenue sources, and other pressures to become more efficient—pointed to the need for functional improvement.

Leaders of one of UKHC’s organizational components, the University of Kentucky College of Medicine (UKCOM), decided to implement a shared services business model in place of inefficient and costly duplicative efforts.

When units share certain administrative functions—such as finance, billing, and IT—staff can become experts in their specific function and in university policies and procedures, serve many units, and increase productivity of transactional work. But getting to that point requires a massive undertaking. The implementation of any new model must include senior leadership, to provide vision and support; central office staff, to analyze and develop new processes; school and department administrators, to lead the change process for deans and chairs; and the transactional staff currently performing the work.

UKCOM had its first experience with the shared services concept in 2011, with the establishment of a common call center. All incoming phone calls went to a central number, where operators would address or route the calls. The call center proved a success for scheduling medical and pediatric services because of the relatively predictable nature of the physician and patient flows. Efficiency ratings and the number of “dropped calls” improved.

Many surgeons, however, considered the call center impersonal because it lacked the flexibility, triage capability, and responsiveness of an established surgical practice. These perceived shortcomings later carried over to—and somewhat slowed acceptance of—larger-scale efforts to become more efficient.

The Spark to Start

By 2012, the foundation was in place for expanding shared services beyond the call center. The surgical chairs were already meeting weekly to address common issues, such as recruitment and operating room management. An independent department of otolaryngology had recently been formed but, to avoid additional overhead, it relied on the department of surgery to perform all business functions. Reducing personnel and salaries became more of an imperative when the College of Medicine’s dean called for serious budget cutbacks.

In addition, the college had recently created a surgeon-in-chief position to oversee all departments involved in surgical activity or use of operating rooms (including orthopedics, neurosurgery, ophthalmology, and OB/GYN). Tasked to develop a shared services model within the surgery departments, the new surgeon-in-chief began meeting bimonthly with each department to review finances and help align activities with overall enterprise goals.

From those discussions emerged two significant findings. First, each department had its own unique business and billing practices, which typically depended on one or two people. Whenever one of these key people was ill, out of town, or on vacation, the entire job function would halt and work would start backing up. Second, each department chair typically relied on one trusted employee—unidentifiable by title or skill set—to perform administrative duties.

To assist in the transition to a new business model, UKCOM hired an external consultant, Pricewaterhouse-Coopers (PwC). Our first step was to form several task forces to review existing processes and determine which activities could be effectively shared.

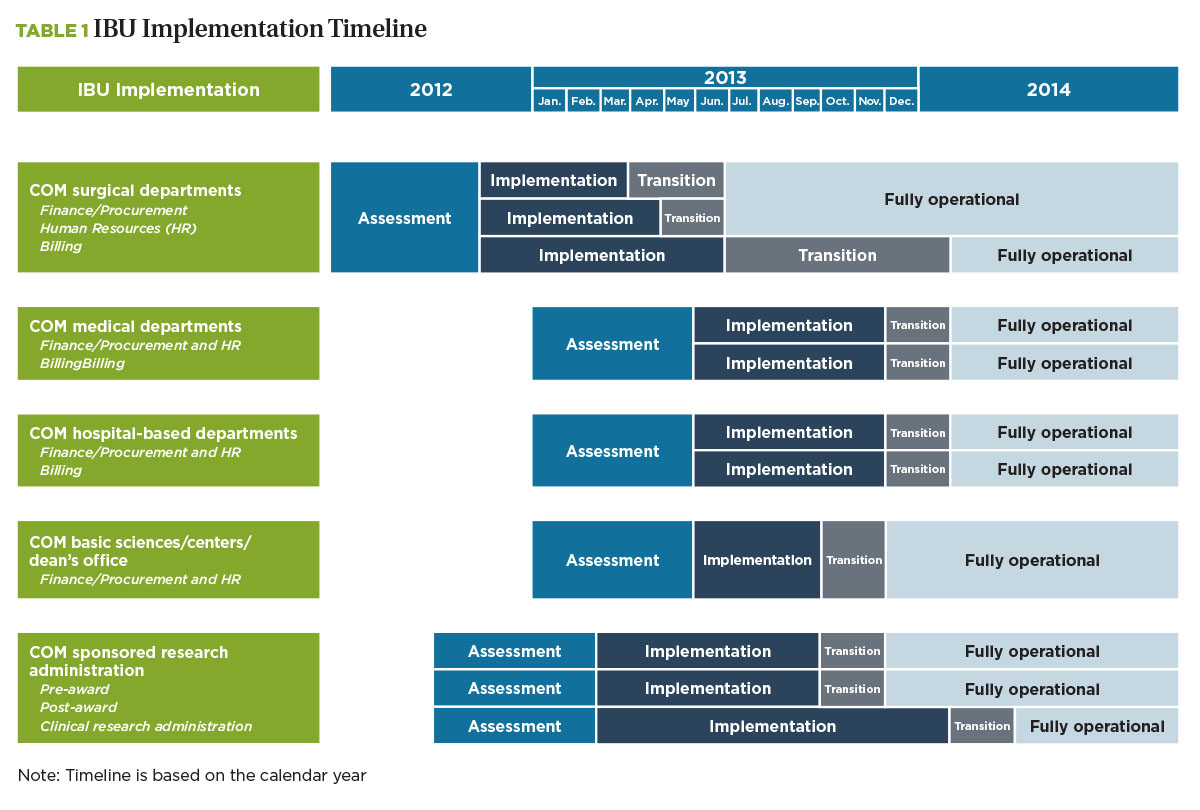

Because each academic medical center has unique departmental structures, technology support, and resource allocation methodologies, a “standard” shared services solution isn’t possible. So, in consultation with PwC, we developed the Integrated Business Unit (IBU) model—an integrated, customer-based approach to functional processing, technology enhancements, and staffing expertise. This work would eventually expand to become part of the overall implementation (see Table 1, “IBU Implementation Timeline”).

Leading the Way

The surgical department served as the pilot program for implementation of the IBU model. Based on PwC’s initial assessment, we determined that the finance, procurement, human resources, billing, and research administration functions should be pulled out of individual surgical departments to form the IBU that would support all those departments. We considered including faculty support (administrative) services but deferred that area until a later phase.

To estimate the staffing size for each functional area of the IBU, we relied on industry benchmarks and determined what day-to-day functions could move into it. In the surgical area, for example, the assessment pointed to a staffing reduction of 13 full-time equivalents (FTEs).

For the IBU pilot in surgery to succeed—and serve as the model for future implementations—it needed the full, continuing support and endorsement of UKCOM leaders. We assembled a leadership team consisting of the college’s dean, executive associate dean, senior administrative officer, and a faculty champion—in this case, the surgeon-in-chief.

The leadership team, which met monthly to review and discuss progress, operated on four assumptions:

1. The new model was a vision that needed further refinement by implementation task forces.

2. Specific functions in the integrated business unit needed input from chairs, faculty, and administrators.

3. Unit staff sizes and potential savings from eliminated positions were only estimates and required further review and analysis.

4. A “new hire” approach would allow the best fit of skill sets, reduce the number of staff, and provide an infusion of new talent from outside the UKHC system. That meant all restructured positions would be posted as “new hires,” requiring current employees to apply and interview for the reduced number of new positions.

During the pilot project, the leadership team proved invaluable in encouraging buy-in among the initial group members in the face of two major challenges.

Each department had a long history of being fiscally independent. Therefore, staff jealously guarded the department’s business functions. Individuals needed to be “sold” on the benefits of shared services beyond cost savings. When surgical chairs and an administrator visited the site of another shared service model, they could “touch and feel” its functional success and developed a sense of “we can do this.”

Certain individuals considered their departments off-limits. Even some physicians who fully understood and supported the shared services model still approached the consultants, the physician champion, and the dean to grant them an “out.” The discussion with these department chairs, directors, or well-funded investigators always followed the same script: “Look, I am all for this IBU business, but you have to understand that my group is exceptional. We are already maximally efficient and, therefore, we plan to opt out of the IBU.”

The dean held firm and did not allow any unit to opt out of the surgery IBU. This steadfast resolve did not waver when other units, centers, and hospital-based departments subsequently issued similar challenges to shared services. We are convinced that if even one had been granted an exception, the IBU implementation would have failed.

A Family Approach

As the shared services model took root in the surgical area, we began assessing other areas. Using the surgery unit as the model, the overall concept was to group other areas together, based on their dominant activities, and form IBUs to support them by handling finance, procurement, HR, and hospital billing functions. Once the workflow had been defined, we’d fill the newly created IBU positions with the best candidates.

The College of Medicine ended up with five such “families”:

- Surgery—centers on operating room utilization.

- Medicine—relates to inpatient and clinic functions, including internal medicine and pediatrics.

- Hospital—centers on hospital-based services, such as radiology and emergency medicine.

- Basic science—focuses on depart-ments such as anatomy, physiology, and toxicology.

- Sponsored research administration—serves principal investigators throughout the College of Medicine, regardless of department.

We also established functional service committees concentrated on finance and procurement, billing, HR, and sponsored research. These committees, made up of representatives from the different IBUs, ensured consistency, standardization, training, and policy implementation across the organization. They developed, for example, the standardized processes and workflow approvals needed to support electronic documentation.

When a policy issue arose, for example, that particular functional committee made recommendations to the executive committee. For an issue specific to one family, such as medicine or surgery, that group addressed the situation and then reported its experience to the executive committee. The functional committees also contributed to the new team environment taking hold in the various academic and clinical units.

This vertical and horizontal integration created a new way to share functions and establish standardization in the college. The “checkerboard design” also helped foster communication and cross-fertilization of ideas among the IBUs. In addition, the faculty champion aided communication among physicians, the business units, and the administration.

Lows and Highs

For UKCOM, making the transition from department-based management to a collegewide integrated functional business unit became a two-year journey— with the project’s complexity requiring a significantly longer time frame than we originally anticipated.

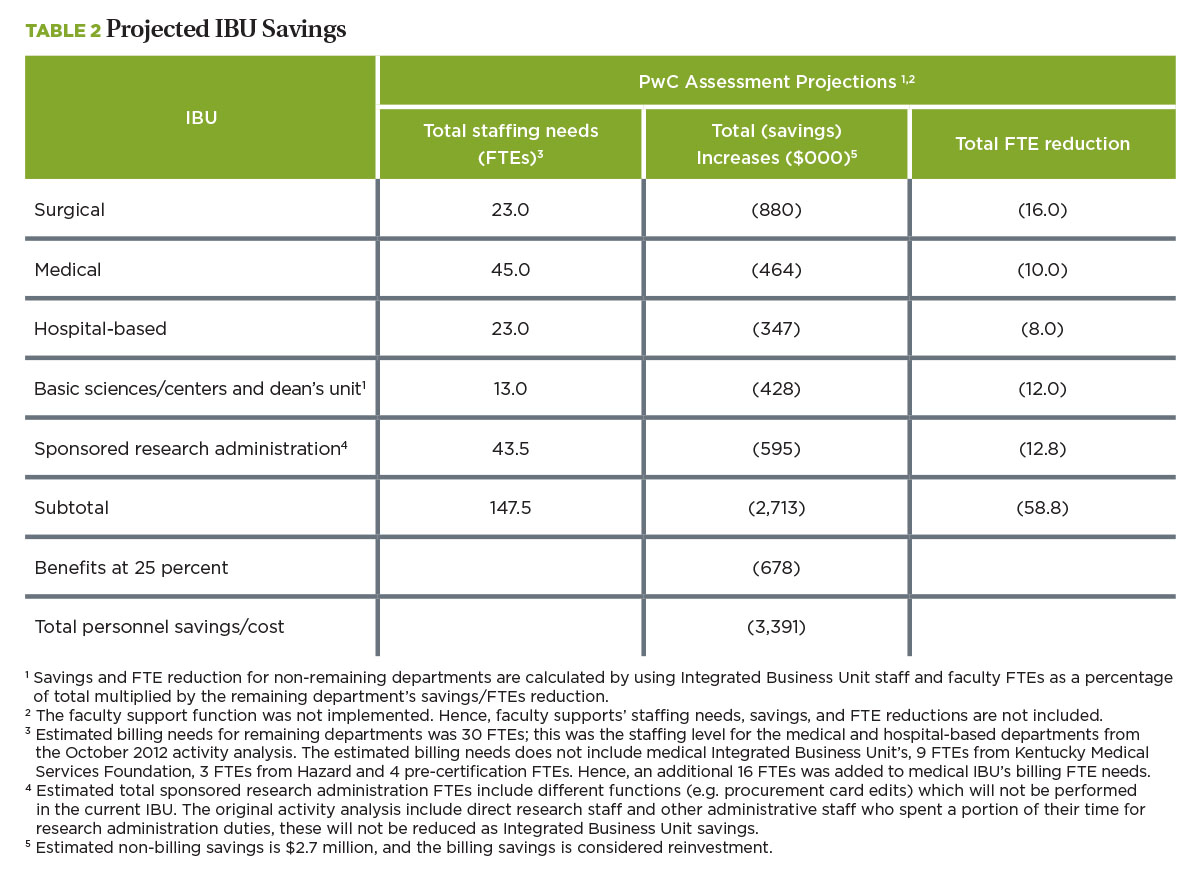

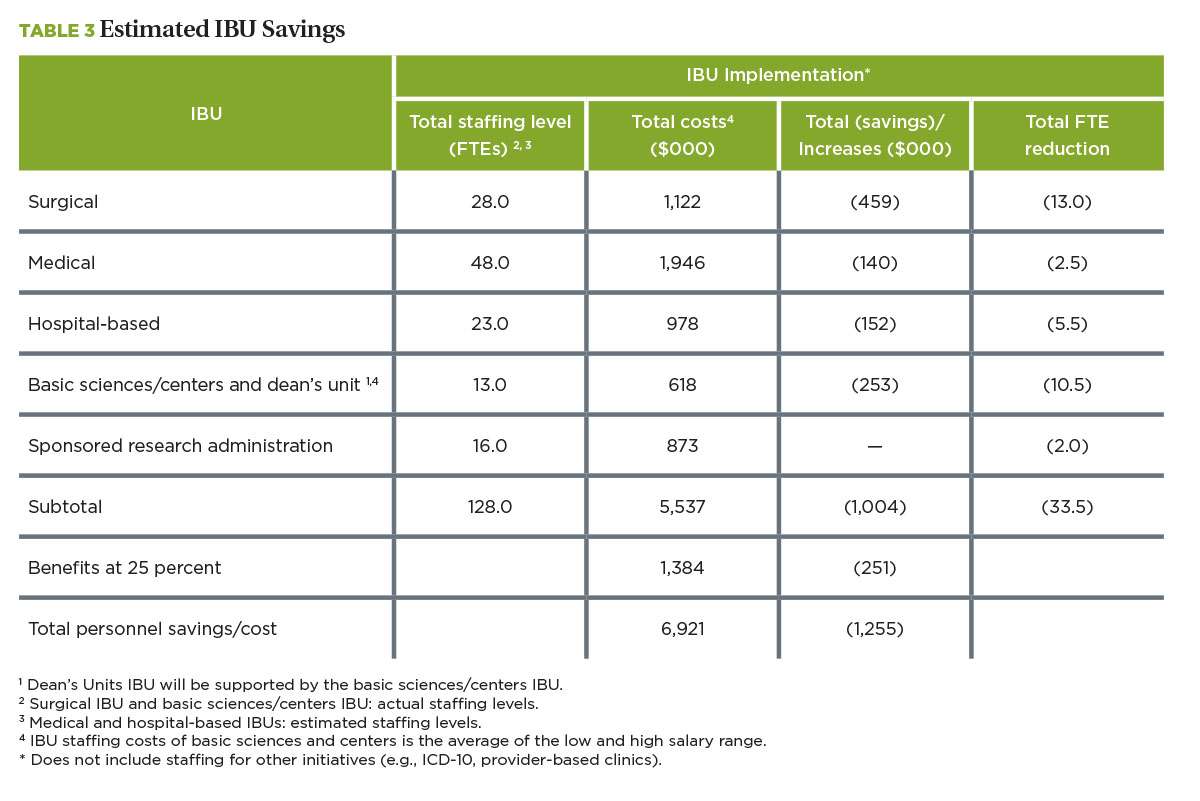

The estimated cost savings (see tables 2 and 3 “Projected IBU Savings,” and “IBU Savings, Progress To-Date”) proved overly optimistic as well. Initially, we projected $3.4 million in potential cost savings, primarily from 60 FTE reductions. Our actual FTE reductions totaled 34 and produced savings of about $1.3 million. Any efficiencies or departmental savings gained through reorganization, however, were immediately reinvested toward ongoing growth, so budget reductions were never achieved.

However, transitioning from departmental silos to a process-centric IBU model introduced a number of significant positives: economies of scale, improved business processes through the development of electronic workflows, and improved customer service by minimizing staffing disruptions due to vacation or illness. Specifically, our gains included:

- Enhancement of the college labor pool’s skill set, with all IBU positions considered as “new hires.” About 50 percent of the new positions went to external applicants; the best-fit internal candidates filled the other half.

- Conversion from a physician-based system of coding physician services to a professional coder-based system. Hiring and training professional coders to verify the physicians’ selections has streamlined electronic billing; positioned the college to be better prepared for ICD-10, the new coding system; increased compliance; and provided more data for strategic planning and decision making.

- Faster, electronic processing of expense reimbursements and leave requests.

- Development of standardized reconciliation processes and user-friendly reports. This allows us to manage financial performance in and across departments.

- Shared purchasing services (in some areas).

In addition, the IBU project produced some unexpected secondary gains. For example, the department chairs became more involved in operational solutions. Senior leadership began interacting more with office personnel. Also, standardized operating procedures developed within the IBUs have been widely shared as “best practices” for making office operations more efficient throughout the university.

The restructuring and business practice changes eventually became integrated into the administrative culture, effectively putting an end to the duplication of efforts and functions across the college.

F. JOHN CASE, formerly with PricewaterhouseCoopers, is now senior vice president for operations and chief financial officer, Morehouse School of Medicine, Atlanta; and JOSEPH B. ZWISCHENBERGER is chairman of the department of surgery, University of Kentucky College of Medicine, Lexington.