Thanks to our adoption of a responsibility-centered management (RCM) budget model, implementation of a program review process, and use of a new data analytics platform, colleges and departments at the University of South Dakota (USD), Vermillion, are seeing a clear picture of where they’ve been, where they are currently positioned, and where they are going. Our intent was to enable informed decision making that would ultimately increase the institution’s efficiency and connect the allocation of resources to institutional priorities.

After moving to an RCM budget model in FY13, we enhanced the financial responsibility of our institution’s eight colleges and schools, including the state’s only medical and law schools. We believe the decisions that make a difference occur at the department level. With an RCM model, colleges and units not only control their resources, they also make strategic determinations about where to invest their resources moving forward.

The Need for Data Analytics

To make knowledgeable financial decisions, our deans needed more information on cost drivers, such as the number of sections offered, the number of credits taught, and the number of enrolled students. In 2014, we made a decision to implement data analytics software to provide the deans with this necessary information.

In 2015, we selected the Nuventive integrated software platform at a cost of just over $50,000 a year, with startup costs of slightly under $50,000. It took us almost 18 months to become fully operational. We released the platform to colleges and schools in incremental stages, instead of all at once, in an effort to minimize pushback from colleagues who resist change—particularly fast, overwhelming change. We deliberately rolled out the platform step by step—and combined it with intensive high-touch training—to reduce any anxiety and cultural resistance. The training included sessions by the software vendor, individual sessions by the provost office staff, and group sessions by USD’s Center for Teaching and Learning.

During the roll-out phase, we took four important steps:

Meeting with stakeholders. After presenting our plan to the university senate multiple times, we began meeting with our key stakeholders—deans and department chairs—to introduce them to the software. The Center for Teaching and Learning, which helps faculty with their classes, served as our internal training arm. We found out that individual meetings with stakeholders worked best because the adoption of a new concept often takes several iterations and demonstrations.

Asking departments to identify goals. Accredited units were already familiar with goal setting. However, the non-accredited units, especially in arts and sciences, didn’t have goals, and some found that tying their goals to action plans and student learning outcomes was unfamiliar territory.

During the first go-round, we entered each department’s goals into the platform and asked, “Now that you have defined your goals, what actions will you take to accomplish them, and how can you connect them to the university’s strategic plan?” The chairs were individually trained on how to enter their departmental action plans into the system. The chair, dean, and provost typically sign off on action plans and goals for each department.

Coordinating efforts. We worked with a number of different units on campus to prepare for the launch of 11 dashboards. After our IT and Institutional Research offices pulled the relevant data, our IR office created the dashboards, which display easy-to-read data available to faculty, chairs, and deans.

Tying data to goals. In 2015, we began connecting our data to department goals and to the university’s strategic plan. Although several departments were able to accomplish this relatively quickly, completion of this process across all units has been slow. To accomplish our university’s strategic goals—from increasing overall student enrollment to increasing the number of degrees awarded to students from different backgrounds—we realized that it was the colleges and departments that not only had to commit to meeting the institution’s goals, but also had to understand the essential value of data in helping accomplish those goals.

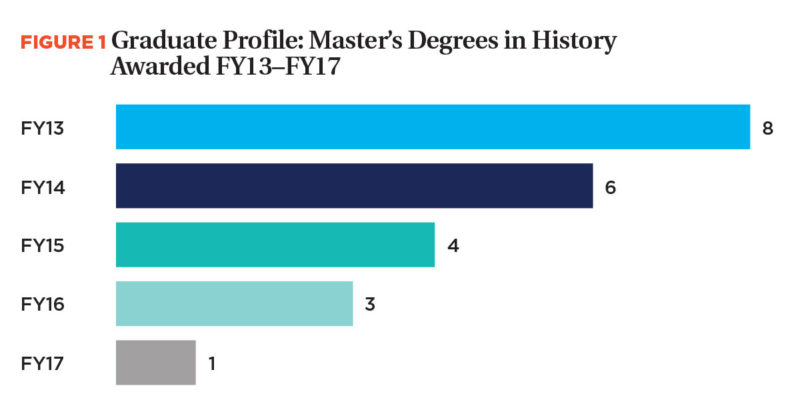

Figure 1 depicts the five-year-period trend for awarding master’s degrees in the history department. According to the state board of regents’ guidelines, institutions are required to graduate an average of three graduates per year (recently increased to four) over a five-year period. The trends show that the history department needs to take actions to address the risk of falling below that benchmark.

Source: University of South Dakota

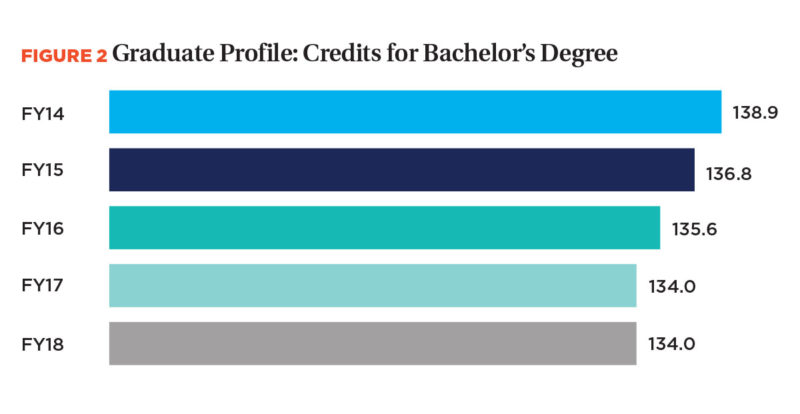

Figure 2 shows the decline in the number of credits at graduation for those pursing a bachelor’s degree. This decrease is in line with the South Dakota Board of Regents’ decision to reduce the required number of credits for an undergraduate degree from 128 to 120.

Source: University of South Dakota

Data-Driven Actions

Our software platform became fully operational in May 2017, and faculty members can see for each department the five-year trends for student enrollment, completion, retention, research grants, credit-hour production, number of sections offered, and graduate outcomes. The data can be aggregated in a number of different ways, such as by enrollment, major for spring/fall, Pell/non-Pell, undergraduate/graduate, ethnicity, or part-time/full-time students.

Our initial thought was to allow faculty to only see their own data, but that became difficult to manage. Instead, we decided that full data transparency might motivate units to pay attention to their goals. Transparency allowed the departments to be aware of what other units were doing and how other units viewed their action plans. We do, however, restrict some data to the individual unit, including department goals, department student learning outcomes, and the assessment of both.

This treasure trove of data facilitates program reviews, which our board requires for non-accredited units every seven years. Before we acquired the data analytics software, the department chair of the program being reviewed asked the IR and budget offices for data. Now, most of the central data are available to departments on a daily basis.

Departments are using these metrics in a variety of ways to move their programs and the university forward. Here are five examples of how our departments are creatively applying data to improve outcomes:

Aligning two programs. When students majoring in the earth sciences program dropped from 25 to six and a tenured faculty member in that major retired, a program review determined it was time to take action. Fortunately, we saw an alignment between earth sciences and sustainability, a specialization we were trying to build, which had experienced a jump in enrollment from six to 25 students over the same period of time.

We moved the sustainability specialization out of biology, moved earth sciences out of physics, and created a new department with a major of sustainability and environment that combined faculty from those two areas. We were able to strengthen our undergraduate program and build new graduate programs.

To their credit, the tenured faculty members in earth sciences, who were most affected by this move, examined the data and recognized the advantages and helped build the revamped program.

Reassigning instructors for introductory courses. In some units, students get excited about a potential major when they take the first course, so it stands to reason that a knowledgeable and charismatic instructor can dramatically influence the number of students who decide to pursue a major. Students who are enthusiastic about their anthropology 101 experience think, “Maybe I will major in anthropology instead of psychology.” The music department recognized the popularity of the instructor of Music 100: Rock and Roll Appreciation, and offered additional sections in the spring semester. This change increased enrollment by 61 percent (460 credit hours) from 2014 to 2018.

Reaching out to high schools. We’ve also seen faculty get much more engaged in outreach to high schools for recruitment of new students, which was once seen only as the province of the admissions office. For instance, our theater program is bringing Shakespeare to rural communities, while various science faculties have become engaged in the state’s Science Olympiad. These activities, which may help increase student enrollment, show that departments are paying attention to, and aggressively pursuing, their action plans.

Looking at specializations. During a program review of chemistry, we noticed a decline in undergraduate enrollment. Because we have a strong component in health sciences at the institution and have found medical biology to be popular among undergraduates, the chemistry department is considering developing a specialization in medical chemistry.

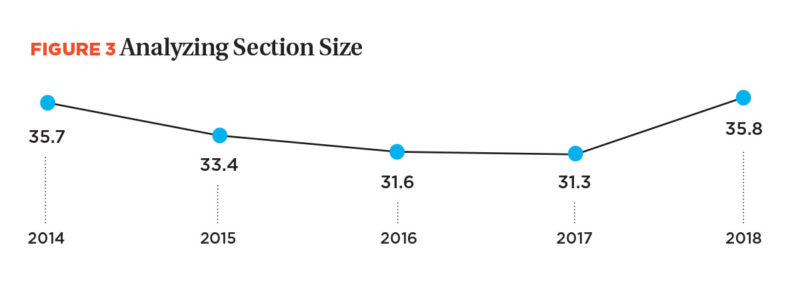

Examining section size. Deans are looking at their average number of sections and their average section size to see if current class caps are appropriate. For instance, if a dean has two sections with eight students, then the dean can seize this optimization opportunity and combine the two sections into one.

Figure 3 provides information on the average section size for the psychology department. With this data, the department can analyze whether the section size is a function of offering fewer sections (defined as increased efficiency) or a function of increased student demand (indicating the impact of departmental recruitment or marketing efforts).

Source: University of South Dakota

Improving Student Progress

We look at our software platform not as an expense, but as an investment that allows us to make strategic decisions campuswide, and improve student retention and outcomes.

We now better understand where our students are and what they need. With fewer students graduating from high school, retention has become critical to our institution and other campuses across the country. We’re not just looking at first-year students; we’re also paying more attention to transfer students because both sets of students influence the bottom line.

We’ve moved our four-year graduation rate from 25.6 percent for the class entering in 2006 to 41.6 percent for the class entering in 2013. According to our data, students who attempt to take 15 credit hours their first semester, as opposed to 12 or 14, increase their graduation rate by 10 percent. So we shifted graduation requirements from 128 hours to 120, and adopted the “Finish in 4” campaign to persuade students to enroll in 15 credit hours per semester.

To help students save on tuition, we looked for hidden prerequisites, focused on offering sections to facilitate student progress, and reduced the credits required for graduation. In mathematical sciences, for example, the average credits at graduation dropped from 154.8 in FY14 to 134.0 in FY17, saving each student about $6,000 in tuition.

We have also offered four-year academic plans and yearlong registration, which encourage students to think long term. For example, our preregistrations four weeks prior to the fall 2018 semester were up 7 percent over the previous year, and were at the highest point in a decade. This represents 137 students or a potential revenue increase of about $1.4 million in the upcoming academic year.

Our yearlong registration, small section sizes, and faculty-to-student ratios allow us to use enrollment reports to say, “Ryan isn’t registered for the spring semester.” As a result, departments are personally calling or texting students, saying, “Hey, we see you haven’t registered. Is there something we can do to help?” Sometimes when it’s a fiscal problem, they can work with the foundation or financial aid office to help Ryan and keep him on track for completion.

These are a few things that we are doing to keep our students and drive their movement to graduation, because student completion is the most important thing we can do for affordability.

Hard-Won Advice

What we have learned from our foray into data analytics is that the process should never be entirely about the numbers. The numbers provide us with information; they do not drive our decisions. The numbers help support the process of inquiry. It is our responsibility to look at the data, find answers, and then clearly communicate our decisions to faculty and administration alike.

We also offer these tips, which business officers may find helpful in their search for more informed, data-driven decisions:

- Implement an RCM model. The traditional government model of “use it or lose it” does not demand that departments be strategic with their finances. When departments are responsible for their own successes or failures—and are provided with the necessary data—they become more strategic in their spending. They also actively search for ways to create revenue and grow programs.

- Make action plans a priority. When we assess department outcomes, we place more importance on the actions taken to meet goals than on whether the goals have been achieved. Why? One of the downsides of goal setting is the dean who says, “I’ve got 40 students; my goal in five years is to enroll 41.” Really? As opposed to 60? We expect goals to be realistically aspirational. That’s one reason why we place a priority on the steps taken to achieve goals.

- Consider how to control and govern data. We were fortunate: The idea of one true data source was readily accepted on our campus because we hired an experienced IR professional who was skilled at presenting information in an understandable format. Although we still run into issues on governing data—who is responsible for what—we are working through them.

- Ensure that departments commit to the institution’s strategic plan. We can search for the word “enrollment” in the platform and see every department that has that word in its goals and action steps. We can do the same for terms such as “diversity” or “inclusion,” which are also integral to our strategic plan. What’s especially actionable and interesting is that we can also see the departments that have not mentioned “diversity” or “enrollment” in their action plans.

Expectations for each unit are different. If a department with 12 students does not have enrollment as a goal, we know that we need to have a conversation to get faculty members thinking about the issue and what they can do. At the same time, another department may have increasing research grants as its most critical goal, and enrollment increases may not be necessary.

- Emphasize training. Instead of group seminars, we recommend frequent meetings with individual chairs. That’s what we found most beneficial. We often met with chairs in their own offices, rather than have them come to ours, so that they could sit at their desks and get hands-on experience. Just because chairs receive data tools, it doesn’t mean that they will know how to use them without repeated practice.

Also, remember that after your platform is up and running, you can’t stop training. Keep refresher courses on the calendar because people come and go from departments.

- Carefully choose your dashboards. Ensure that the information is relevant and will be used by departments in budgeting, program evaluation, enrollment analysis, and regional accreditation. Another caveat: Don’t put out too much information at one time, or it becomes overwhelming. We ended up eliminating one of the dashboards we created—student credit hours per faculty—after several deans advised us that its information could be perceived as threatening and, as a result, could create resistance to the tool’s adoption and acceptance.

- Offer a carrot. A few of our schools have increased their capacity in course sizes. Because they have increased efficiency, they generate additional net revenue. Schools then keep and use this revenue for a variety of special projects, such as offering research and travel stipends. Their increased work earns departmental rewards.

- Cycle results back into the platform. Goals, strategies, assessments, revisions, and data are all built into the platform. At least annually, we ask department chairs to identify the steps they have taken to achieve their department goals. Did their strategies work? When were they initiated? Do they need revisions? Users enter information into the platform throughout the year. This iterative analytical process is never static.

What’s Next?

Another benefit of our data analytics platform is that we can better predict revenue. For example, we can look at retention from fall to spring on our dashboard. The general overall campus retention is about 78.8 percent. We can look by individual departments, where the range may be from 70 percent in political science to 85 percent in biology. This information allows us to get more specific with our revenue projections.

Moving forward, we’re building additional platforms that provide information to departments on finances, individual faculty workload, and student credit hours per faculty. This data will let us compare ourselves to similar departments in similar institutions to see where we stand.

We have learned that when you empower people with data, they are more likely to make good choices. They feel like they are part of the process as opposed to being told what to do. We’ve seen that deans and department chairs can be partners in their institution’s success through the successes of their respective units.

MATTHEW HEARD is an instructor of health services administration and management in the Beacom School of Business, and JIM MORAN is vice president for accreditation and student success initiatives, University of South Dakota, Vermillion.