At the University of Kansas, change has become more routine than the arrival of the state’s spring tornadoes.

First came the university’s bold new strategic plan, introduced in October 2011, to boost academics and research. Conceived during the 2010–11 academic year, Bold Aspirations tackled six main goals focused on overhauling the undergraduate experience, positioning research for emerging strengths and societal benefit, and leveraging partnerships for public impact. (For further details, see sidebar, “Metrics Don’t Lie.”)

Next came the administrative overhaul to pay for it.

“The strategic planning process involved a steering committee of more than 50 people, plus subgroups, task forces, summits, and focus groups,” recalls Diane Goddard, vice provost, administration and finance, University of Kansas (KU), Lawrence. “We involved hundreds of people. As that process started moving along, we realized it was very academics driven. We had lots of faculty involvement and needed a way to engage all the staff. We also realized that to do many of the things we were talking about, we needed more resources.”

Thus was launched Changing for Excellence, an ambitious administrative makeover with three primary goals: Be more efficient, save money to throw in the strategic plan’s pot, and improve services.

After conducting an RFP and eventually hiring Chicago-based Huron Consulting Group, KU put 11 areas under the microscope: the budgeting process; shared service centers; construction; domestic enrollment management; international enrollment management; facilities; human resources; libraries; procurement and sourcing; research administration; and information technology. For each area, Huron created a detailed business case outlining expected savings, investment costs, risks, and implementation plans.

Goddard admits she was initially surprised at the full-scale deployment. “Out of the 11 business cases studied by Huron, I thought we would start with two or three,” she says. “Instead, we moved forward with all 11.”

KU leaders didn’t want to waste any time moving ahead, according to Mike Phillips, senior director of Huron’s higher education practice. “There was a desire by KU leadership to not wait a couple of years to get underway,” he says. “They were committed to making the changes sooner, rather than later.

“You can always go in and cut one or two areas and free up some money,” he continues, “but if you want deep and lasting change, you need to think of it as a transformational effort and look across all areas, and then have the heart to go after it.”

The initial projects—facilities consolidation, HR process redesign, procurement, and strategic sourcing—began in November and December 2011. Here’s a look at where three of the initiatives—IT, shared services centers, and procurement—stand today.

IT Delivers Double Whammy

When Bob Lim first joined KU in 2011, people were reluctant to work with IT, recalls the chief information officer. “We were an afterthought, because we weren’t transparent, we weren’t providing the service our customers wanted, and we weren’t doing any type of outreach.”

Even so, IT was selected as one of the several initiatives to proceed without Huron’s ongoing assistance. Coordinating across both the Lawrence and Kansas City campuses, Lim was charged with:

- Centralizing servers.

- Reorganizing and redefining IT staff and organization.

- Increasing usage of multifunction devices for desktop printing.

- Implementing a single identity management system across all campuses.

- Optimizing network capabilities.

- Leveraging software purchasing.

“In a higher education environment, our culture is to encourage and allow collaboration with each other,” Lim says. “Because higher education has always been a highly decentralized arena, organizations have hired their own IT folks within their areas. As technology evolved and organizations became more complex, units were building their own solutions and not integrating with each other. With 20,000 students and 10,000 faculty and staff, we needed a better way to manage technology on campus.”

His challenge was to integrate, centralize, and find duplicate resources across the university and then realign those resources for teaching, research, and strategic missions. Translation: His team took possession of 700 servers from across the university and moved more than 50 professionals to the IT payroll, bringing it to a total of 275.

“This was a double whammy,” Lim admits. “Not only did I have to tell everyone, ‘I’m bringing your servers, your people, and your money into IT.’ I also had to promise we would deliver better service.”

To say many departments resisted the IT changes would be an understatement. Comments ranged from “You will destroy what I have built during the 20 years I’ve been here” to “This will never work.”

Although the implementation hasn’t always been easy, Lim reports that 97 percent of IT customers are now happy with the service provided.

“Our customer satisfaction is at an all-time high,” he says. “I knew this process was going to work when people began reaching out to me to partner on technology and nontechnology projects. I knew this was going to work when our leaders began seeking us out in the beginning of the discussions, rather than in the middle. And, I knew this was going to work when I no longer had to convince deans and leaders of IT’s value.”

Shared Service Centers

Nothing about the administrative master plan generated quite as much discussion and controversy as shared service centers and whether they should be implemented at KU.

“That was a big ‘if,’ honestly,” says Jason Hornberger, assistant vice provost, shared service centers. “We ultimately decided to implement shared services, but there was a fairly intensive study period where we had to decide if this was the right thing for KU, how it would impact the university, whether we could be successful, what the scope would be, and what activities we would include.”

After visiting various campuses with shared service centers that were in different states of maturity, KU leaders opted to develop a regional shared service center model in which each of the five centers distributed around campus serves a specific group of customers. Functions concentrate on human resources, finance, and post-award research administration.

“When you implement a new project like this, you have to look at your landscape and funding structure,” Hornberger says. “We didn’t pick anybody’s model specifically, but tried to select one that would custom fit our university. We tried to take those types of transactions that were common across our campus.”

Hornberger explains how the model plays out in everyday work functions: “If a staff member from the English department transitions to a shared service center, he or she continues to support the English department in HR, finance, or post-award research administration. If the English department keeps that person busy only about 50 percent of the time, we assign the individual to another department as well. It’s helpful if the relocated staff members can continue to support their home departments, because they have relationships there and know how their former departments work. If we can also provide them with an opportunity to support French and Italian, another language area, they can get to know new faculty members and learn and broaden their expertise.”

Before and during the transition, KU placed a high priority on being respectful of employee preferences. “We ask employees if they want to move to a shared service center,” Hornberger says. “There are a couple of camps. Some staff members want to move; others don’t. Quite a few are on the fence and want more information.”

Hornberger also asks potential employees what kind of work they like to do. “If they like to do the work that is moving to the shared service center but want to stay in the department, they may not be happy. We can’t in all cases meet the desire of the employee, but we feel that we need to ask, and it’s usually a good place to start.”

Looking back, he thinks that implementing the first shared service center was his biggest hurdle. “I can talk about something until I’m blue in the face and say, ‘this is a good idea,’ but I had nothing to demonstrate what our shared service center would look like. Once we brought up the first shared service center and moved those staff members in March 2013, we then had a learning lab to show other departments.”

KU avoided problems experienced by other institutions by involving stakeholders in the design of the new system, reports Jeffrey S. Vitter, provost and executive vice chancellor. “Our shared service centers are getting better and better ratings,” he says, “because people become specialists and perform at a higher level. The staff loves them, and the departments are adapting.”

Now a division within administration and finance, the shared service centers currently employ 120 staff members. Hornberger estimates completing the initiative, which is about halfway finished, in the summer of 2016. “We’re taking our time. We’re treating every department in a unique way. We’re not just shoving people into a box.”

Re-engineering Procurement

In the past decade, perhaps no business process at KU has been more dramatically altered than procurement.

“From 1865 until 2006, KU was subject to the state of Kansas procurement statute,” explains Barry Swanson, associate vice provost for campus operations/chief procurement officer. “We are a state agency and had to follow the same statute as the departments of transportation, corrections, and other state agencies. In 2006, we reached out to the state, and ultimately to the legislature, to reform that process, because higher ed is not government. We need greater flexibility and different processes to function efficiently.”

After a three-year pilot project, KU in 2010 received permission from the legislature to make the autonomy permanent. “In the days [in which] we were a satellite office of the state, everything over $25,000 had to go to Topeka for processing,” Swanson says. “Once we got the autonomy, it became clear we needed to re-engineer the office because the state didn’t use any e-procurement technology. We needed an update.”

The opportunities identified by the procurement initiative were (1) to develop a strategic sourcing program as part of ongoing operations; (2) implement an e-procurement solution to streamline approval and settlement; and (3) merge purchasing and accounts payable to form one unit: procurement services.

“A technology unit administers our procure-to-pay system, which is based on SciQuest software,” Swanson says. “We merged payables and purchasing to leverage the utility of the technology and take advantage of other business process efficiencies. It was really a matter of modernizing our processes and procedures.”

The initiative took procurement from a manual process that relied on procurement cards to a technology-based process. “It completely streamlined purchasing,” says Swanson. “If you want to get down to brass tacks, this organizational change has given us the data to generate better contracts that save money for the University of Kansas. The technology and the changes in business processes provide us with data we never had before, which allows our staff to put together better procurement tools.”

With procurement being one of the first of the university’s areas to be tackled, this initiative was started in 2011 and took 18 months to complete. “The unit has been reconstituted, the technology has been implemented, the new processes are all working, and the advisory committees are set up,” Swanson says. He adds that the advisory committees meet with procurement staff to determine which opportunities to pursue for future sourcing events.

Both the Lawrence and Kansas City campuses now use the SciQuest technology. “We’ve implemented a consortium module, which is an administrative layer that sits on top of each of our SciQuest instances, so we’re all using the same contracts and have consolidated reporting ability.”

Talk, Talk, Listen

Before the initiatives could reach the point where they are today, KU leaders and consultants did their share of talking—and listening—to stakeholders.

“Communication and inclusivity are key,” Phillips insists. “We didn’t have just a half dozen people at the top working this project and then telling everybody how it would turn out. We had workgroups, committees, subcommittees, and task forces. We routinely involved middle management and staff in core activities.”

KU also took full advantage of other communication vehicles:

- A Changing for Excellence website http://cfe.ku.edu/index.php became a communication tool for information and updates on each of the 11 initiatives.

- Town hall meetings, which were live, as well as closed-circuit broadcasts to remote locations, routinely filled two or three auditoriums simultaneously around the four KU campuses. “Sometimes we would have different topics presented in different venues so those interested in service centers could come to one venue and those curious about the budget redesign process could go to another,” Phillips says. “Shared service centers and facilities consolidations were the ones that drew big groups.”

- Suggestion/question boxes allowed faculty and staff to anonymously make suggestions or ask questions about the initiatives. The questions and answers were posted on the Changing for Excellence website.

One communication technique that encouraged buy-in, according to Phillips, was to present challenges to the assembled employees and ask them, as a group, to come up with solutions. “That adds value, because when they are back with their co-workers, they can indicate what’s going on and how it isn’t just people in the ivory tower shoving change on them,” he explains. “If you can make the need for change understood and let employees participate in the ideas and decision making about the best way to get there, it fosters overall buy-in. You can’t do this kind of change in a vacuum. You have to have broad participation.”

Another technique endorsed by both Goddard and Phillips: Have the consultant, in this case Huron, dispense at town hall meetings the unpleasant news that change is necessary. “There’s a time to have the consultants out in front to take the heat for suggesting sweeping changes to the institution,” Phillips freely admits. “But once leaders have adopted the strategy and made the decision to go forward, KU people need to be out in front, making the case for change. While we sometimes may switch as to who was talking to the crowd, Huron and KU worked as a team to make it happen. We were both working toward the common good.”

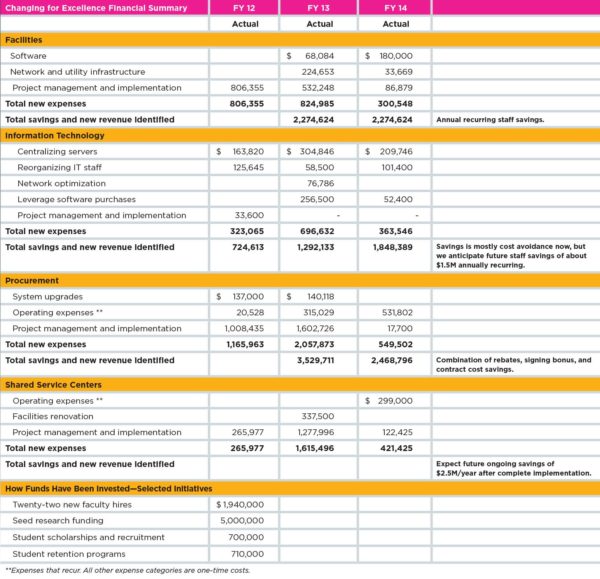

KU Project Management Financials

Lessons Learned

In the three years since the administrative makeover began, KU leaders have learned a number of lessons that they hope will help business officers who are leading change management efforts at their institutions:

Be absolutely sure you have unwavering top-level support. “Your leaders have to have the stomach for this,” Goddard emphasizes. “They have to understand that if they look away, change is not going to happen. Had either the provost or the chancellor wavered in their resolve, it would have been all over. We wouldn’t have been able to do this.”

She points out that faculty and staff will most likely harangue leaders with questions and appeals such as, “Why do we have to do this?” or “This is changing my life,” or “We’ve never done it this way.

“Our leaders have been able to resist the pressure to cave,” she says, “which means that finally after three years, people are realizing they can’t wait us out. Now we’re finally bringing some of the more reluctant people along. They’re not all happy, but they’re coming along.”

Carefully select champions. Don’t appoint initiative leaders based on their ranks or positions, cautions Goddard, particularly if they show any resistance to the changes being proposed. “We had to have champions who were extremely excited about what we were about to do,” she says. “We picked those leaders very carefully, and then we had to really support them along the way.”

Focus on swaying the undecided. In Goddard’s experience, people react in three ways when confronted with change. “You’ll get one or two people who instantly get it and get excited,” she says. “You will have a number who think you are absolutely stark raving mad. Then, you will have a whole bunch of people who are sitting on the fence. That’s the group you have to be most concerned about. You can either win them over or lose them.”

Take full advantage of available technology. “When they need to achieve goals or milestones, organizations no longer talk about adding people,” Lim asserts. “Instead, organizations are using technology as a multiplier. It’s much more practical.”

Swanson agrees. “All of the initiatives are intertwined by technology,” he says. “You really can’t talk about procurement without talking about shared services or the IT reforms. They’re all one continuum that blends together.”

Provide training. “We asked a professor in our public administration school who focuses on change management to do a huge training program for everybody involved in any initiative, so we all had the same groundwork,” Goddard says. “That helped tremendously because we had a whole team of people trained to help the smaller workgroups find their way through difficult things they had to do.”

The professor, Marilu Goodyear, conducted training for both the strategic plan and the administrative makeover.

Stay in touch. Encourage departments that lose employees to a shared service center or another functional unit to stay connected, urges Danny J. Anderson, dean of the College of Liberal Arts and Sciences. “Maintain personal contact with your shared service center staff. To keep that relationship strong, they should continue to be treated and viewed as a part of your staff.”

He also suggests notifying employees only about four to six weeks in advance that they are scheduled to become a part of the shared service center. “When you give more time, it creates an atmosphere that magnifies anxiety and doesn’t help people become constructive in how they successfully make the change,” Anderson observes.

Don’t overlook the staff members who remain behind. “You can’t focus on just the staff moving into the shared service center,” Goddard advises. “You have to spend just as much time focusing on the staff remaining in the department. You have to spend just as much time helping the chair think about how he or she will restructure the work, because the person is not sitting right down the hall any longer.”

Anderson, who volunteered to host the first shared service center in his college, agrees. “The units that were proactive and redefined the position descriptions for their department staffs, and thought about the new ways they would supervise and communicate expectations to them, have had a much easier time and have been much more successful.”

Keep your promises. “KU has kept its promise not to lay off people, taking the kinder, gentler approach when dealing with personnel issues,” Phillips says. “Throughout this, there was no intent for any kind of reduction in force. The message we sent from Day One is ‘Everybody’s got a job. You may be working in a different role or different place, but everybody’s got a job. We’re just going to rearrange how we get things done in the hopes of making things more efficient.’”

Goddard adds that she couldn’t—and wouldn’t—do a “slash and burn,” while, at the same time, asking administrative staff to tolerate the intense levels of change associated with adopting new business processes and systems.

“If I were to say, ‘And you have to worry about losing your job,’ I’m not going to get people to put the kind of effort into this that they are. You have to start by changing the culture. Once you’ve got everybody committed to changing the culture, you’ll be able to generate the savings,” she says.

Margo Vanover Porter, Locust Grove, Va., covers higher education business issues for Business Officer.