EDITOR’S NOTE: This article is based on the presentation “More Productivity, Less Space: Rethinking the Academic Office,” one of many sessions at NACUBO’s 2015 Annual Meeting in Nashville. The presentation—focused on designing office space that better aligns with the way people work, thereby increasing productivity and cost savings—drew a full house and much commentary. Business Officer invited the presenters to tell their story.

An effective work environment is important for any organization to carry out its mission. In higher education, effective places in which our faculty, staff, students, fellows, and visiting scholars can interact and conduct their work are essential. On most college and university campuses, office space makes up the largest proportion of the nonresidential space inventory, frequently totaling in excess of 25 percent. Yet, this resource is often underutilized and poorly aligned to meet the needs of today’s employees and the ways in which they prefer to work. The result can be workspace that is simultaneously costly to operate and maintain, and inefficiently used.

The dilemma of empty offices is as old and recurring a topic as that of vacant classrooms on Friday afternoons. What to do about the problem of office utilization is the challenge. Campus culture, departmental politics, individual status, manager preferences, and history compound physical limitations of old buildings and obsolete standards. The truth of the matter is that you won’t solve your space problem by treating it as a space problem. What is required instead is a broader approach grounded in a comprehensive workplace strategy.

With the right strategy in place, campus leaders can situate the role of and need for office space (type and quantity) in the broader context of human resources, information technology (IT), and physical goals and constraints.

What follows are (1) an overview of workplace strategy; (2) models for advancing ideas of workplace change; and (3) examples and lessons learned from a pilot implementation of a new workplace program at the University of Minnesota, Minneapolis.

Start With Your Strategy

A good starting point is to understand and write down your current workplace strategy. Then, begin to develop a basic plan to achieve organizational goals by applying an evidence-based, holistic approach to aligning facilities, IT, human resources, and finances with academic, program, or operating unit objectives. This process includes establishing goals of relevance and importance to the institution and the college or operating unit, as well as to the individuals who will work in the space.

The importance of setting goals that are mutually beneficial to the institution and the individual cannot be overstated. Failing to do so means you are working against yourself. Every workplace has a whole set of practices, rules, or behaviors that—lacking a formal strategy—act as the de facto strategy. Odds are that this accumulation of past practices is not closely aligned with the organization’s current goals, and may be shaping the workplace in unintended ways.

How organizations or units go about developing their workplace strategies and goals will vary, but several components are common to successful strategy development.

- Because of the multiple stakeholders involved, successful workplace design requires a collaborative, stakeholder-driven process designed to drive adoption and to achieve larger strategic goals. Consider positioning your new idea in what industrial designer Raymond Loewy calls the “most advanced yet acceptable” (MAYA) approach. In other words, you need to find the sweet spot or the tipping point that determines how far you can stretch the acceptance of the majority of employees for working in new and innovative ways.

- Understand how new ideas are evaluated and the factors people consider when adopting them. To move from acceptance of the concept to adoption of the actual process requires convincing people of the merits of the new idea or strategy.

- Carefully craft the communication messaging for your new idea. Whether as a space concept, a new budgeting process, a new organizational structure, or something else, the story you choose to tell becomes your strategy. How you talk about something suggests how you want others to perceive and embrace it.

Innovation Adoption Framework

Before attempting to make significant changes to the workplace, college and university leaders would be well served to first step back and understand the process by which new ideas are adopted. Fortunately, a rich history helps inform the process, going back to the social science theories of Everett M. Rogers, detailed in his 1962 book The Diffusion of Innovations (The Free Press). By studying how people adopted innovation in corn seeds, Rogers identified a pattern that has since been extrapolated to a variety of fields and served as the foundation for much of what we know about innovation today.

Rogers recognized that new ideas created by innovators are adopted sequentially, starting with “early adopters” who are interested in trying new things and are influenced by the media and by setting trends. Next, those who are in the “early majority” are influenced by their peers and will adopt an idea if or when it becomes practical. A “late majority” of individuals will jump in when they see that everyone else is on board. Finally, the “laggards” change only when they are forced to do so.

Rogers also identified the five key factors people generally consider when deciding whether to adopt an innovation: (1) the ability to observe it in use; (2) the ease with which they can try it out; (3) the degree to which it is simple versus complex to understand; (4) the degree to which it is compatible with their current systems and behaviors; and (5) the relative advantage it provides. These five factors are useful criteria for designing the workplace planning and change management programs. For instance, tours of other spaces enable individuals to see people working differently; pilots allow people to try it out; and clear communications can explain tomorrow’s workplace strategy, how it relates to today, and the benefits it offers.

University of Minnesota’s Story

The foray of the University of Minnesota (UMN), Minneapolis, into developing a more comprehensive process for managing workplace change grew out of an institutional effort to reduce space-related operating costs. In broad strokes, the initiative originally focused on emphasizing renewal and replacement projects in the capital plan, rather than those involving net new space; developing new space-management tools; and seeking opportunities to decommission obsolete buildings. While UMN’s space utilization initiative was focused on “space” to the exclusion of other underlying issues, the comprehensive review of ways to reduce costs led university leadership to look more broadly at workplace strategy tools and bigger-picture issues regarding university workplace concerns.

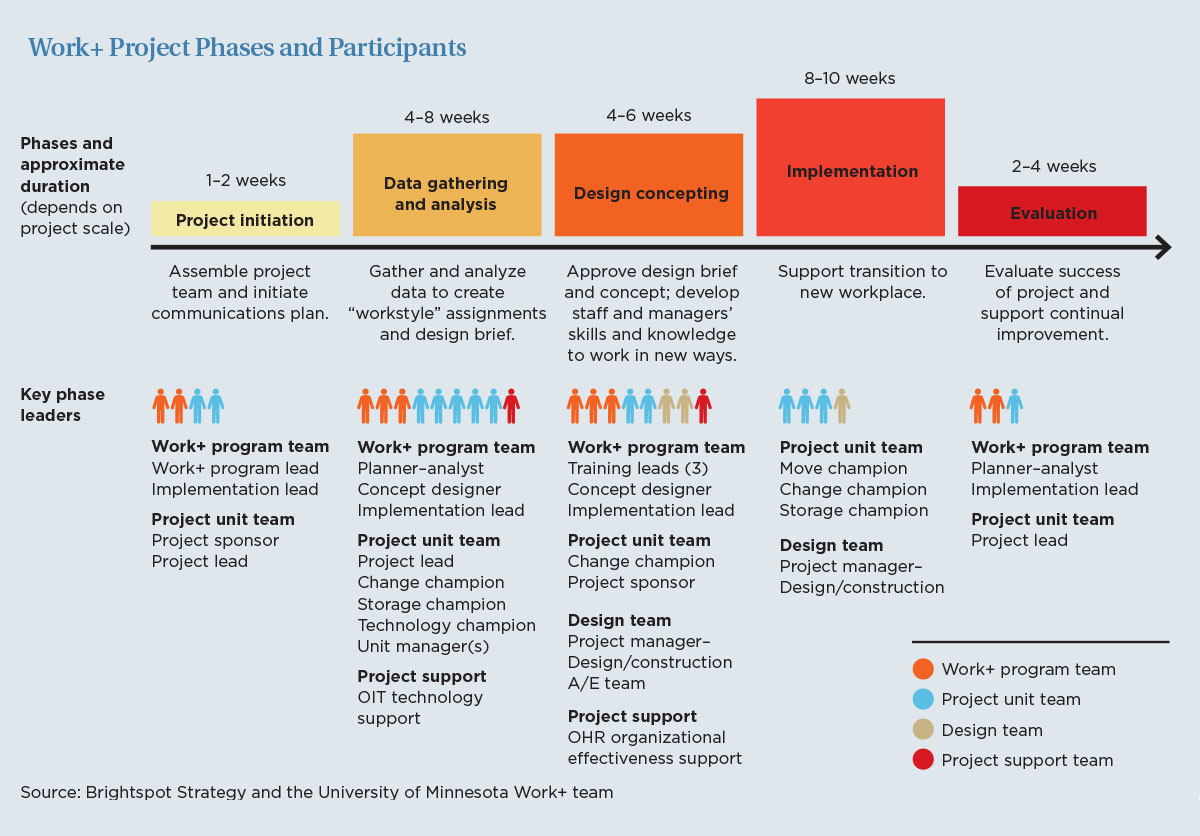

To help the university transition its thinking from strictly one of space assignment and rigid space models, the university partnered with Brightspot Strategy, a strategy consultancy, to develop an alternative workplace strategy program. The initiative was internally branded as Work+ to convey that the primary purpose of the plan was not about using less space—though space efficiency would be part of it—but rather, about making the workplace more effective, more efficient, and ultimately more satisfying for employees.

The Work+ Model

From the outset, campus and group-level needs guided the project, which acknowledged that the nature of work is clearly evolving: it is increasingly technology-rich, collaborative, global, and mobile. The existing space-planning process, where one person equals one desk (along with limited meeting and amenity spaces), did not effectively support this evolution in the nature of work. There also is not one set of needs within the workplace, but rather, multiple sets of needs based on individual roles, generational differences, and other factors.

Taking these shifts into consideration, we developed the Work+ program around the following four defining characteristics.

Integration of space, technology, and training. The model guides planners to think holistically about these workplace elements and consider the three components in an integrated way, when evaluating everything from the profile of the program team to the project process, research activities and tools, and structure of workplace recommendations. This integrated approach can be explained by an analogy to hardware and software: The space and technology (hardware) only function if you also give its users the appropriate training in skills, policies, and culture (software) to make the best use of it.

Skills, policies, and culture are critical. Moving into an environment that looks and feels different and is created with different assumptions about how people will work meant that we needed to reset and guide people with a new set of norms on how to use what would eventually be their new workplace at the university. As part of our work, Brightspot consultants and the university’s organizational effectiveness and IT groups co-developed a set of training modules:

- Establish new ways of working. Understand how to organize your day to work wherever you are most productive.

- Review workplace storage. Assess current filing practices and options and then create future filing norms.

- Manage flexible teams. Learn how to set goals to guide work and measure progress among a more mobile workforce.

- Learn workplace technology. Learn how to use tools for voice communications, data, and collaboration for activity-based work.

- Establish workplace norms and protocols. Collectively establish the norms and culture for a space in order to make the most of it.

Use of work styles. A more nuanced space plan considers not only the size of the work group and its overall needs, but also the needs of individuals. To accomplish this, we used an approach called “workstyles,” which are basically profiles that describe (1) how individuals work in terms of their mobility (how much time they spend at their desks, away from their desks in their primary building, and away from their desks on campus); and (2) the level of individual interaction (how much of their time is spent working alone and collaboratively).

By analyzing each work style, you can determine different types of spaces required to support individual work, shared collaboration, shared amenities, and shared support. When taken together, the work styles of a staff group begin to shape the overall space program—clarifying how much of which types of spaces are needed for the workplace.

Creating neighborhoods. Neighborhoods bring together a mix of spaces, driven by work-style calculations. First, this means thinking not in terms of individual desks and offices only, but rather, considering the variety of places in which people can choose to get work done—open meeting areas, meeting rooms, phone rooms, kitchenettes, lounges, desks, and offices. Second, it means organizing those places into neighborhoods. As in a great city where communities mix homes with stores, restaurants, parks, and schools in close proximity, the workplace should bring together these different spaces so that people can move fluidly between them, according to their work style.

Participatory planning. The planning process involves end users—occupants of the future workplace—in analyzing the current situation, shaping the future vision, forecasting and validating future needs, and making the transition.

This high level of engagement in the planning process is done for two reasons: (1) when properly facilitated, participatory processes simply create better ideas because there is more input and more consideration of the ideas presented; and (2) by involving people in determining their own future, the move to a new space and new ways of working within that space feel to the occupants less like a change imposed from the outside or from above and more like a change they elect and have a say in shaping. This participation takes place through interviews, surveys, workshops, and observations about how space is being used.

Piloting the Program

In 2012, UMN’s Office of Human Resources (OHR) was undergoing strategic renewal to transform its traditional, siloed, transaction-focused HR model to one that was more efficient and collaborative. “One OHR,” as the initiative was called, focused on cross-unit collaboration as well as differentiating between routine and strategic work. In this regard, the department was an ideal candidate for the Work+ pilot, because of its need to address space, technology, and organizational challenges all at the same time. The department also met the minimum viable neighborhood group size of at least 30 to 40 staff. With approximately 50 people, the workgroup was big enough to require a variety of collaborative spaces that were derived from analyzing employee work styles.

The project’s vision resulted in recommendations that the department:

- Enable employees to be engaged and connected.

- Support a wide range of work activity.

- Equip staff with the technology and training needed to collaborate with colleagues and customers both in person and remotely, as well as to digitally create, share, refine, and store work.

- Create confidential and private meeting spaces and work areas through tiers of access.

- Reduce and improve storage solutions.

Initial Results

The pilot brought staff together from six locations into two sites to support cross-unit collaboration and shed unoccupied space. This resulted in a decrease in the average assignable square footage per person (in some cases by nearly one half) and a nearly twofold increase in collaborative space, while continuing to provide dedicated workspaces to individuals who required them. (Approximately 40 percent had “resident” work styles, with assigned spaces; and 60 percent had “mobile” work styles supported by shared spaces.)

Overall, the new environment reduced work space by 25 percent to 35 percent, while expediting business processes by more than 50 percent. To assess other tangible and intangible outcomes, post-occupancy evaluation of the pilot included a survey identical to the pre-move survey, interviews with users from a variety of departments, and walkthroughs of the new space.

Feedback from evaluating the new environment identified both positive outcomes and areas that still needed improvement.

The benefits. Among the positives, staff indicated an increased satisfaction with respect to environmental factors, formal and ad hoc meeting support, and the sense of energy in the workplace. They also appreciated the ability to work collaboratively and share information. Staff’s sense of being part of “One OHR” also increased, although somewhat at the expense of intradepartment cohesion.

Employees also reported a decrease in the amount of time at their desks and an increase in the amount of time collaborating with colleagues, along with a perceived increase in the importance of teamwork. Some also reported saving time by receiving faster feedback from peers and managers. One interviewee said, “To solve a work question with colleagues, the first thing I’ll do is look around and see if they’re on the floor.”

The needed improvements. Acoustics and concentration remained a challenge for some staff, with much better collaboration coming at the slight expense of concentration. These shortfalls highlight the importance of continually evaluating and tweaking the workplace and providing training refreshers. Leaders also should not ignore the importance of addressing the seemingly “small stuff,” such as storage of items like books and coats; and the impact of ambiguity on employee satisfaction. In a mobile environment where more space is shared, clear rules for what is and is not acceptable behavior for the group become more important. Detailing acceptable workplace behaviors and norms, as well as preferred solutions for such issues as storage of personal items, should be based on broad input to ensure acceptance.

Lessons Learned

Reflecting on the overall Work+ program progress as well as the pilot with “One OHR,” several strategic and tactical lessons emerged that can help other institutions, regardless of the type and scale of change an organization seeks through a new workplace strategy.

- If it does not already formally exist, develop a workplace strategy that is “most advanced, yet acceptable” to the organization.

- Don’t lead with space as your primary or sole goal. Rather, consider space as a means to achieving your goals.

- Find your early adopters and early majority to ensure that you have a critical mass to adopt a new workplace strategy, and become the champions who move the project forward.

- Start small, introducing changes incrementally so that people can acclimate, test ideas, and provide feedback.

- Obtain broad leadership support for the proposed changes, but limit project scope so that a single leader is tasked with and capable of making the necessary decisions to advance the project.

- Create a participatory process where staff help create their future workplace and the norms by which they all agree to abide.

- Give people the opportunity to see the proposed changes in action and ideally try them for themselves.

- Continually communicate throughout every aspect and phase, because your story is your strategy.

Finally, anticipate continual change and follow-up. Know that physically moving to a new workspace is not the end of the journey, but the beginning of a transition for everyone learning to work in new ways regardless of place.

BRIAN SWANSON is assistant vice president of finance, university services, at the University of Minnesota, Minneapolis; ELLIOT FELIX is founder and director, and YEN CHIANG is a senior strategist at Brightspot Strategy, New York City, a consultancy that helps organizations change in ways that improve customer and staff experiences.