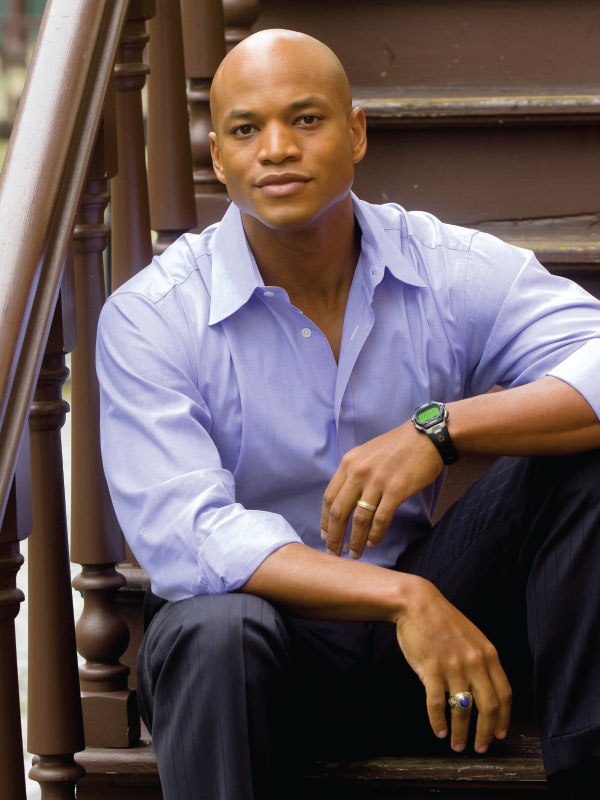

Two kids with the same name—Wes Moore—lived within blocks of each other in Baltimore. One Wes Moore grew up to be a decorated combat veteran, banker, Rhodes Scholar, White House fellow, and social entrepreneur. The “other” Wes Moore, however, is serving life in prison. How can such radically different destinies be explained?

What helped him in life, says the successful Wes Moore, was a strong support system that was made up of family members and several mentors. This foundation had a tremendous positive influence on him and ensured that he had access to higher education, which, in turn, opened up a plethora of opportunities and experiences.

At the NACUBO 2015 Annual Meeting in Nashville, July 18–21, general session speaker Moore will take a leaf out of his own book, The Other Wes Moore, to offer his views on ways colleges and universities can achieve better outcomes. For example, by teaching students to expect more of themselves, institutions encourage students and future leaders to consider higher education, persist in earning a degree, and engage in internships. All this can set the stage for a more fulfilling personal and professional life. In an interview with Business Officer, Moore explains how institutions can achieve this and more.

As a banker, combat veteran, Rhodes Scholar, White House fellow, and a social entrepreneur, you’ve held leadership positions in many organizations and worked with top decision makers. What are some of the qualities you’ve observed in effective leaders that have influenced your own approach to the role?

One of the exciting things that I’ve seen—on the combat side, the finance side, and the government side—is that effective leadership characteristics are relatively universal. There are certain qualities that leaders demonstrate, and these override the different industries and organizational areas. We’re talking about a leader’s ability to bring people on the same page, and unify them toward a specific target. That’s been one of the fascinating things to learn and see about this process. I’ve observed a level of connective tissue that runs across the various organizational specialties.

The three common traits that I’ve seen among leaders are (1) being technically competent, (2) having a strong degree of common sense, and (3) taking care of people. People need to be able to trust their leaders and, in turn, leaders must be able to trust their teams and rely on them to complete important tasks. That’s how such tasks are accomplished.

To what extent were your perspectives, goals, and persistence shaped by your military experience? How can military training apply to young people in preparing them for success?

One thing that the military does really well is introduce leadership into the lives of young people, something which I think matters significantly. Because the one thing we know about our young people is that they’re going to learn. The only questions are: What are they learning, and who are they learning from?

We have kids with Type A personalities. They want to be recognized and want to be responsible. They want to be leaders. And, if we don’t come up with positive aspects and elements that allow them to partake in that, then other people will fill that void—not necessarily in good ways. That’s where I think that the military was really helpful to me—it allowed that void to be filled in a way that was not just positive, but also gave me a greater sense of where I wanted to go.

Can you share some things that you learned with regard to higher education?

We are seeing seismic shifts in higher education. They’re happening at an incredibly rapid rate, and many forces are involved in creating those changes. There’s an access force and an evaluation force, which are finally putting higher education on the forefront of our national conversation. Now, more than ever, we are seriously looking at what access really means and how evaluations really affect our students.

The thing that’s supremely important about the field of higher education, and the work that we’re doing in it, is to never forget about exactly who it is we’re supposed to be fighting for in this bigger conversation—the students. It is about providing access and opportunity, not just so that a student can graduate, but so that he or she also has opportunities after completion. That’s one of the things that has become exceptionally important in this higher education conversation.

In your book, The Work, you write that “culture, climate, and leadership” explain the difference between two Baltimore schools that are just two miles apart, have similar demographics—and yet one of them is successful and the other one isn’t. Talk about this concept. What were the obvious differences in the way the two schools approached these three critical points?

First off, I want to say that both of these schools are doing fantastic work to support our students. The fact that the teachers and administrators show up on the front lines for our students every day is exceptionally powerful.

That being said, there are small shifts in culture, climate, and leadership that can make a huge difference. The most important thing that we have to understand is that our students will live up to the expectations their leaders have of them, no matter what those expectations are. A student whose support network expects him to complete college will do it. But a student who does not have that support network, or whose teachers expect [him or her] to fall into cycles of violence, will do just that. As a larger society of mentors and educators to the youth around us, we need to understand what our students are capable of. Each one is talented, and we need to expect the most from all the students.

Are these differing expectations also true of higher education institutions; and, if so, what can leaders do to set the kind of expectations that make the system better?

The obstacles might vary in higher education, but the emphasis on leadership and positive expectations is the same.

The slight difference is that in higher education, we need to start teaching our students and future leaders to expect more of themselves. We need for them to realize and understand what they are capable of leading, building, and creating in the professional world. The best way to do this is to encourage our students to engage in internships and externships. As students become more acclimated and comfortable in a professional environment, they will maneuver through the system more efficiently and create tangible positive change.

There are huge disparities between large public institutions and HBCUs (historically black colleges and universities). How can we minimize those differences and make sure that students not only finish, but also have opportunities after graduation?

We need to be honest and address some of the historic and generational funding disparities that exist between the public institutions and HBCUs, and the financial impact of diminishing support coupled with tuition increases. But, we also need to be aware of the particular specialties of HBCUs and the necessary role they play. They create a counter narrative to balance the collective perspective of traditional academic institutions, most of which have a majority White student population. This alternative perspective is very crucial, as we work to make higher education more accessible to all populations.

We need to recognize that diversity in higher education institutions is what makes U.S. colleges and universities strong, and we need to continue emphasizing the importance of such diverse missions at institutions. We need to take a look at the pressing goal to maintain HBCUs because of their historic significance, as well as their current increasing relevance.

Jobs in the future will necessitate an educated population, regardless of race, income, religion, or ethnicity. HBCUs have a proven history of producing educated individuals regardless of their skin color. They have provided education and opportunities to all students in an environment where they can learn comfortably. As we work to increase access and attainment for our students, we should make sure that HBCUs succeed in their mission.

We know that students have difficulty completing their freshman year, and the dropout rate at that level is unfortunate. With BridgeEdU, what are your plans for reinventing the freshman year?

We work with colleges and universities to completely restructure the freshman year because, in many ways, colleges don’t have a college completion crisis. What they have is a college freshman-year crisis. In that sense, we’re losing a vast majority of students at that level.

With BridgeEdU, we add support in that first year with a whole series of wraparound services that the colleges deem to be useful and necessary. We can assist colleges by providing services that range from financial aid support to personalized internships and apprenticeship services, to tutoring and coaching. Those are the assets that we bring to the table, and our evidence shows that these services have been really useful and helpful to our university partners, and to our students.

What specific types of universities do you work with? What criteria do you look for before you approach an institution about stepping in?

We’re looking for universities that, oftentimes, have an access mission. For example, we’re looking for institutions that are price point–sensitive and are relatively affordable for our students. We’re also looking for universities that understand and recognize the need to have a higher student persistence ratio.

There may be certain schools that graduate 97 percent of the students who enroll there, and these institutions may not have as much of a use for us. We also know that those schools make up the vast minority of colleges and universities. Institutions recognize and understand that for many of them, their ability to continue to operate relies on the ability to ensure a higher student persistence ratio, and that’s where we can be helpful.

How many institutions does your organization work with? What are some early results?

Within the immediate Baltimore area, BridgeEdU has partnered with two academic institutions. Our pilot cohort is just wrapping up the year, and we are pleased and excited about the progress we have seen. We are in the process of final evaluations and the results are encouraging.

In your view, what’s the value of education—specifically, higher education?

The argument can feel frustrating because for many students that we work with, the marked difference between their lives, opportunities, and prospects—and having access to some type of higher education credentialing—is so real. And, for many of these students, this idea of going to college or pursuing some form of higher education, is not a realistic conversation.

Being able to pursue and complete higher education is an opportunity and achievement that matters on different levels. One, it gives evidence that you know how to complete something. It shows that you actually know how to persist. And, that matters to employers, partners, and loan officers. It matters to everybody. It is an important, demonstrable accomplishment.

It also enhances your skill set, where you then have other assets that you can lean on and tap into; and it broadens your horizons about what can be possible and available.

The third thing is that it broadens your network, connections, and friendships. People forget that the majority of jobs in this country don’t happen through classified ads or through an online job portal. According to the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, 70 percent of the jobs in this country are gained through connections and networks. If we’re not able to open up these networks and we do not allow more people to tap into that level of social capital, then we’re doing a real disservice to them, their families, and to our societal elements.

Your family and strong mentors have had a positive influence throughout your life. Unfortunately, this is lacking in many of our communities. What’s the importance of having that support system?

I think it gives you a sense of foundation. It lets you know that you can be aggressive about your future and realize that you have a certain level of backstop and support.

It also gives you a chance to think differently and be creative about the types of involvement and work that you want to pursue. Our opinions and ideas are shaped by those who surround us. It becomes crucial, then, that we’re surrounded by people who don’t just give us a positive sense of who we are, but also provide encouraging reinforcement of where we’re going.

I was fortunate enough to have a strong family support system when I was growing up. The unfortunate truth, however, is that not everyone has people in their corner rooting for them. Society, as a whole, needs to recognize this and begin a conversation about the disparity between those who have a strong support system and those who are left to their own means.

The fortunate thing about this problem is that everyone can help. Everyone is a mentor whether they know it or not. We need to recognize this fact and collectively start acting like the empathetic and supportive mentors that we all can be. We are all capable of reaching out to a young person and starting a conversation. It is just a matter of going out there and doing it.

Turning to some issues for NACUBO’s membership, a wave of retirements is taking place among chief business officers, and the potential leadership void is a challenge to many higher education institutions. How can the outgoing CBOs become successful mentors?

People have to remember that mentorship is not something that is nice to do, but it is an imperative thing to do. In addition to thinking about what it does for the other individual whom you are supporting, it also keeps you fresh, interested, and engaged.

We also have to be able to understand that with every person that we’re supporting, with every type of outlet that we’re building now, we’re creating a new and different type of opportunity for not just that young person, but for our larger collective society and community. So, if you care about your own personal life, community, and environment, it only makes sense, then, to have more and more people involved in that conversation. And the only way that happens is if we have mentors and people with experience in their skill sets, who can then make these types of things a reality for people.

What are your thoughts on being mentors to a new generation that has completely different expectations with regard to the career path? It can be a big disconnect in an office setting, as you’re trying to train and mentor those upcoming generations.

It can be a disconnect, but I think it’s important that each side understand where the other is coming from. People should be able to interact and arrive at an understanding that these occupations and industries are changing and evolving. And, that will keep people fresh in terms of how they think about it.

But, at the same time, it’s important for people who are entering the industry right now to understand that they have to be willing to put in a level of time, work, and effort in order to watch their career grow, and to succeed. The right balance can be achieved when people who are experienced in the field actually can lend their support to those eager to learn and grow.

EARLA J. JONES is director, annual meeting, NACUBO.