When borrowing money in the bond market, colleges and universities sometimes obtain ratings from two credit rating agencies. Dual ratings have been used by some colleges to substantiate credit quality. However, analysts at different rating agencies don’t always reach the same conclusion, which then can result in an institution receiving a “split rating,” in which one agency rates the bond issue more highly than the other.

In 2006, George K. Baum & Co., an investment banking firm in Kansas City, Missouri, published a research report on the occurrence of such split ratings. Now, eight years later, we have reviewed and updated this research to find out the frequency and trends of split ratings compared to the 2006 findings. Both reports are based on the activities of the two principal credit rating agencies: Moody’s Investors Service (Moody’s) and Standard and Poor’s (S&P). (Since Fitch Ratings rates a much smaller universe of higher education debt, we have included only S&P and Moody’s ratings, as they were used most often by colleges and universities included in the research.)

Each rating agency has unique rating paradigms and methodologies, placing a different emphasis on various factors to arrive at an independent rating, which can naturally lead to different outcomes. A split rating should not be interpreted as one agency being “easier” or more lenient than the other, but rather as the agencies using differing methodologies to determine their respective ratings. After ratings are issued and the bond issue is sold, the agencies’ surveillance practices as well as institutions’ new issues and covenants can affect rating level.

In general, split ratings have become more prevalent than they were back in 2006. Some of this ongoing volatility can be attributed to the financial crisis, which made rating agencies more proactive and led to their updating and making more transparent their respective methodologies.

Chief business officers (CBOs) should also keep in mind the fact that nonrated debt can have a significant effect on the institution’s overall public bond credit rating. For example, when institutions participate in the private direct placement market, borrowing directly from a bank, that debt often carries no rating and is not subject to the same disclosure requirements as public bond market offerings. However, borrowers need to be aware that since this debt affects the institution’s debt profile, it is still important for rating agencies and bond investors to know details, and it may indeed affect the outstanding rating on their bonds.

Volatility in higher education credit ratings can be problematic for investors and issuers alike, so it is important for institutions to monitor their ratings. Jeff Eisenbarth, vice president for business and finance and treasurer, Rollins College, Winter Park, Florida, says, “This kind of research sheds insight on the different rating approaches of S&P and Moody’s. For example, Rollins College has only a Moody’s rating, and I am being asked why, and if the college should think about a dual rating—particularly when we go out with a new bond issue.”

Our latest research pointed out not only some differences in the rating agencies but also varying impact of the ratings on private and public institutions.

Private College and Universities

For the current research study, we analyzed 370 private institutions, of which 140 (38 percent) were dual-rated. Of the remaining 230 institutions with single ratings, an approximately even number of institutions were rated by each credit rating agency (with Moody’s rating 46 percent and S&P 54 percent).

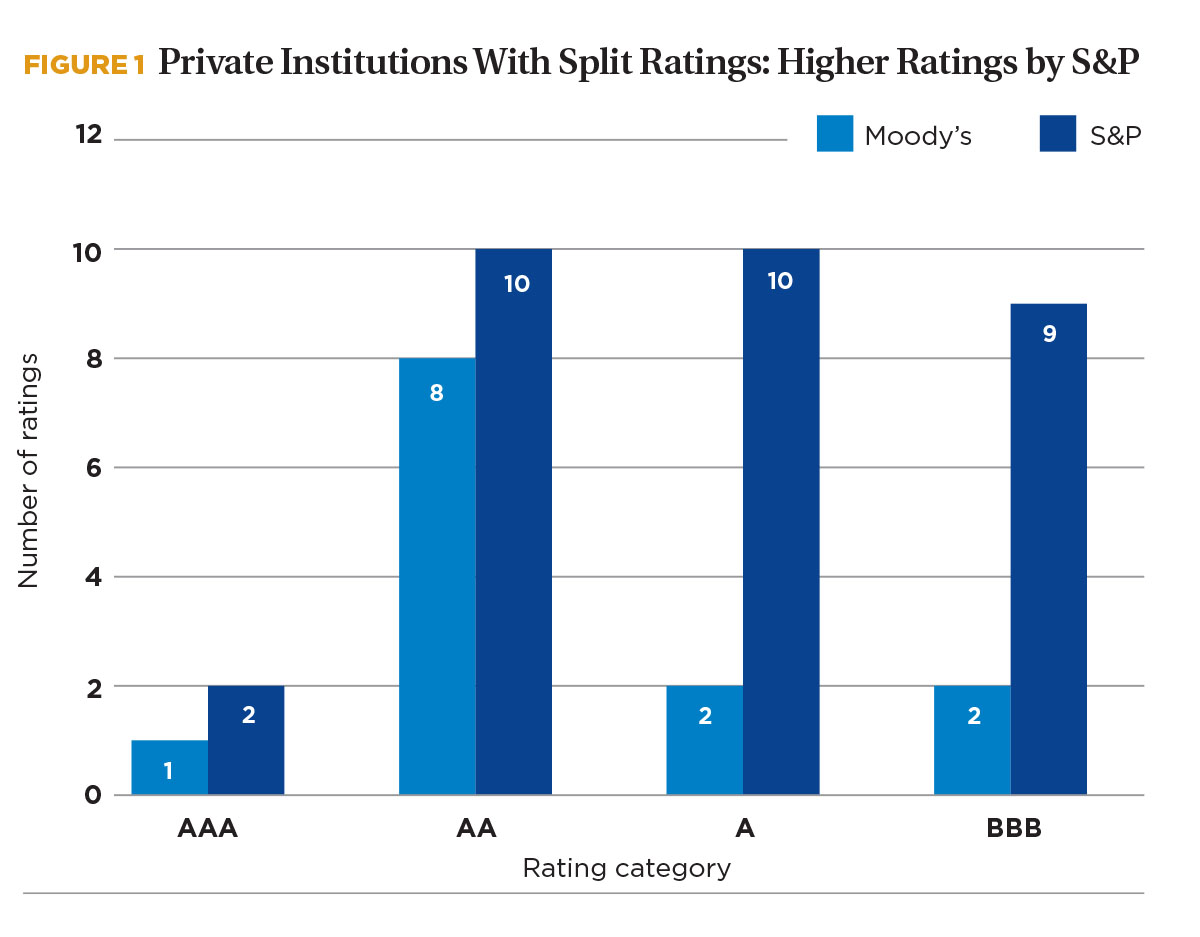

Approximately 31 percent, or 44 ratings, of the dual-rated institutions had split ratings. For each rating category, S&P gave higher ratings more frequently than Moody’s, as shown in Figure 1. Compared to research conducted in 2006, S&P rated higher than Moody’s slightly more often in 2012 for the “AAA,” “AA,” and “A” rating tranches. However, for the “BBB” rating tranche, S&P currently places private college and university bonds in a higher rating category 82 percent of the time, compared to 50 percent of the time in 2006 (for a pool of 10 institutions in 2006, and 11 in 2012).

It should be noted that both agencies have a negative outlook on the entire higher education sector. This differs from 2006, when both agencies had a stable outlook on the sector. At that time, higher education demographics were still growing, endowments were appreciating, and parents’ ability to pay for tuition was not as impaired as it is today.

Public Higher Education Institutions

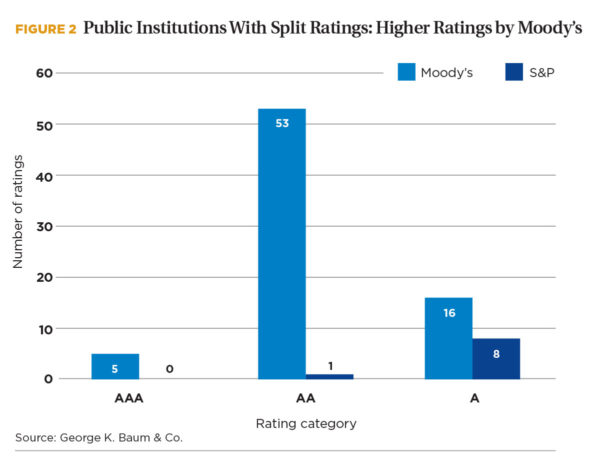

Of the 253 public institutions analyzed for the current report, 120 (47 percent) institutions were dual-rated. Of the remaining 133 institutions with single ratings, an overwhelming 107 (80 percent) institutions were rated only by Moody’s. That most single-rated institutions selected Moody’s to provide their rating correlates to the fact that Moody’s ratings were higher more frequently than S&P for each rating tranche (see Figure 2).

These results are dramatically different from research conducted in 2006, which concluded that there were no notable differences between Moody’s and S&P’s ratings for public institutions.

We believe these differences can be attributed largely to Moody’s recalibration of all its municipal bond ratings in 2010—from the municipal scale to the global scale—which enhanced the comparability of its credit ratings across its rated universe. The recalibration did not reflect a change in credit quality or a change in credit opinion of an issuer, but simply a change in scale. However, as a result of this action, many municipal ratings were upgraded, including those of U.S. public higher education institutions.

While S&P did not recalibrate its ratings, the agency has updated its sector rating methodologies over the past several years. Still, many public institutions wonder why their S&P rating is a notch below the Moody’s rating.

Effects on Bond Pricing

Based on our research studies, it appears that split ratings are more commonplace now than in 2006 for both private and public higher education bonds. If rating agencies differ in their credit opinions enough to result in a split rating at issuance, the interest rates paid by the borrower—or the actual price of the bonds—will often reflect the lower credit quality of the two ratings. Even if the dual ratings are essentially the same at issuance, but subsequently one of the agencies lowers its rating, bond trading prices will likely reflect the lower rating, especially if that rating falls down into the next whole rating category. For example a college rated “A3” by Moody’s and “BBB+” by S&P will more likely trade at rates reflective of the “BBB+” rating.

However, one needs to know that a bond rating category is only one piece of the bond pricing equation. Other important factors include the following:

- The general interest rate environment.

- Bond structure and maturity (fixed rate or variable, repayment schedule, and redemption features).

- Market sector (higher education, health care, housing, and so forth).

- Tax treatment of bonds in the state of issuance (whether there is a high state income tax and if the bonds are double-exempt).

- The supply and demand for municipal bonds at the time of the initial pricing or subsequent trades.

Many other factors influence pricing of individual issues. All things being equal, bond issuers are viewed more favorably with regard to pricing if they are larger, more frequent borrowers, well-known to investors, in compliance with debt covenants, and have filed timely continuing disclosure information. Smaller issuers who borrow less frequently may benefit in pricing from the scarcity factor for investor portfolio diversification, but usually only if they are in the highest rating categories.

Lower-rated small institutions that do not access the market very often and have smaller bond issues (by design) are often passed over by institutional investors with large portfolios. These investors tend to purchase blocks of larger bond issues that are widely held and traded by other institutions, which adds to their liquidity appeal. However, this is the very type of debt that smaller, sophisticated investors—institutional and retail alike—may be seeking, as they may value higher returns over market liquidity for this type of investment.

Because of these considerations and dynamics of the municipal bond market, institutions with outstanding debt should remain cognizant of how their bonds are trading. Such bond trade data is easily accessible at the Electronic Municipal Market Access Web site.

Ron Smith, vice president for finance and administration, University of Idaho, Moscow, stays well informed on bond market trends. “Since the University of Idaho has split credit ratings (Aa3 and A+), we appreciate rating agency research such as this. Our university is in the process of a new bond issue, so we are keenly sensitive to our ratings and their consequence for the university’s cost of capital.”

LEE WHITE is executive vice president, JUDITH HARVEY is senior vice president, and TRINITY LUDWIG is vice president at George K. Baum & Co. Osman Mendoza, intern in 2013, contributed to this article.