At the University of Maryland Baltimore (UMB), a group of facilities staff members and outside consultants have spent more than three years collecting exhaustive data about the components of every structure on the campus. They have recorded the age, condition, expected life cycle, and replacement cost of every roof, window, electrical item, plumbing fixture, HVAC unit, sidewalk, and other such components on campus. With that information, the university has developed a comprehensive facilities and maintenance database to track maintenance needs and timing: To get completely caught up, the database reveals that the university needs to spend $648 million.

“Obviously, we aren’t able to fund $648 million in deferred maintenance all at once, so we have developed multiple approaches for tackling these needs,” says Dawn Rhodes, chief business and finance officer, and vice president for administration and finance at UMB. “The finance and facilities staffs knew that deferred maintenance was an issue, but now it has come to a head, and this database will help us identify and track our needs and the total costs.”

The Baltimore campus typifies the way that many U.S. colleges and universities have been operating for decades, or even centuries. While their buildings and structures have experienced normal wear and tear, many of these institutions have traditionally spent more energy and financial resources on highly visible new construction projects rather than on maintaining the existing structures.

However, as maintenance issues mount, legislatures and institutional leaders are realizing that, while far from glamorous, spending time and money on maintenance can preserve valuable capital assets and avoid future spending on replacements for neglected buildings. Maintaining existing buildings so that they can continue to function as valuable tools for educational purposes is simply good stewardship. Now, the challenge is figuring out how to locate funding and get stakeholders on board to spend big bucks on low-visibility projects.

Maintenance Feeds the Mission

Every dollar spent on facility maintenance is a dollar that could have been spent on research or teaching—but wasn’t, Rhodes says. That tension can make it difficult to justify the funding for deferred maintenance, until stakeholders understand that comfortable, safe, updated facilities are essential for accomplishing an institution’s primary mission of education or research.

Sometimes the people who are closest to the classroom can understand that better than those in far-flung boardrooms. For instance, Johnson County Community College in Overland Park, Kan., is wrapping up a $9.8 million project to upgrade the heating and air conditioning systems campuswide. “It was a hard sell to spend almost $10 million on something that nobody sees, but we were at a critical juncture in terms of building occupant complaints about climate, and we couldn’t control the system well,” says Barbara Larson, executive vice president of finance and administrative services. “The return on investment is positive, not only because of the energy cost savings, but more importantly, because people must be comfortable in order to teach and learn.”

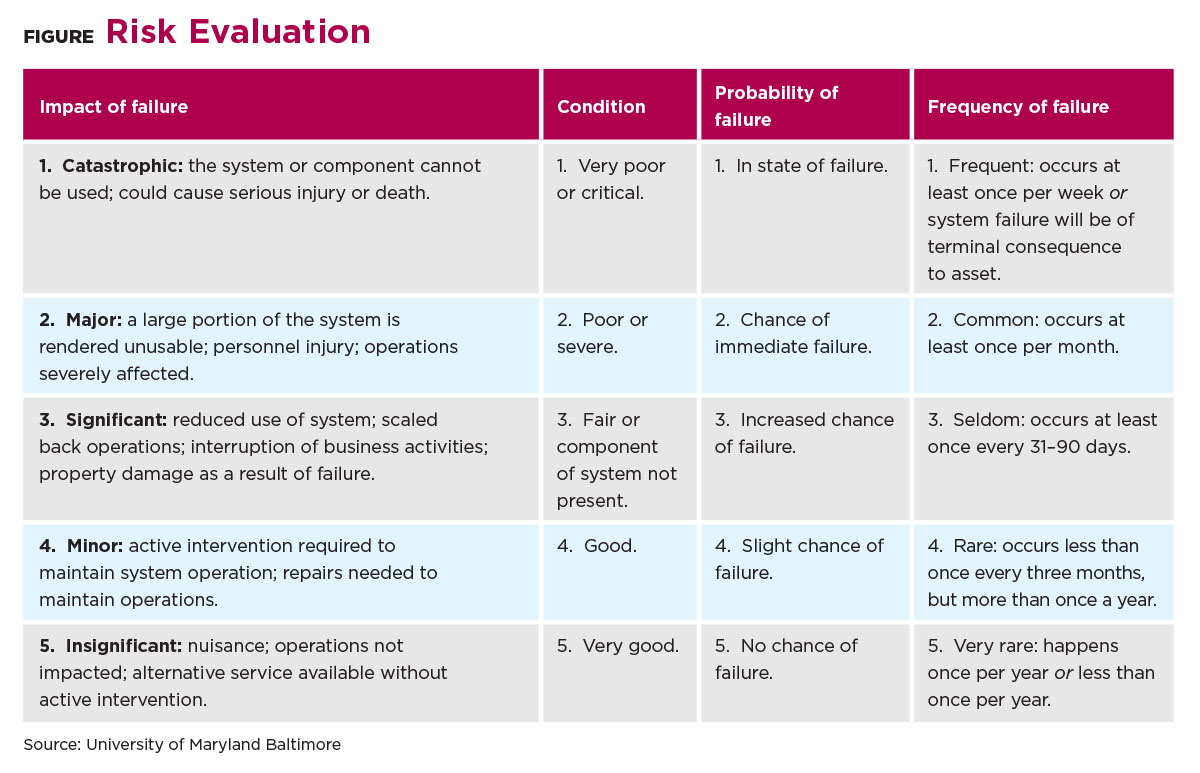

At UMB, the new maintenance database allows for ranking the needed projects based on urgency and provides clear data to leaders across campus. Academic leaders understand the importance of working facilities to their academic missions, and the new data show them how their needs compare with those of others across campus, helping them make decisions about prioritizing their own budgets. (See figure, “Risk Evaluation.”)

For instance, “the dean of nursing saw and understood why we have several projects ahead of hers on the deferred maintenance list. She realized that the maintenance project she wanted for her building wouldn’t rise to the top of the list for years,” Rhodes says. “As a result, she decided to take her own school’s dollars to fund an electrical upgrade in the auditorium, and to repair and update a few classrooms in the nursing building. Some people realize more than others the connection between deferred maintenance and academic outcomes.”

Institution leaders who have invested in completing deferred maintenance projects say the investments pay off in the classroom. Canada’s Carleton University in Ottawa, Ontario, recently saw a dramatic increase in enrollment in the chemistry program after updating lab furniture, services, and fume hoods in its 40-year-old chemistry building, says Darryl Boyce, assistant vice president of facilities management and planning. “We worked closely with the chemistry department and converted four old chemistry teaching spaces into one large modern and flexible teaching space, with enhanced safety and electronic teaching support,” Boyce says. “With the use of technology related to the fume hood controls, we were also able to increase the number of fume hoods with the existing exhaust systems. The enrollment in the chemistry program dramatically increased after the renewal of the undergraduate teaching space.”

At Carleton, as at many institutions, it has taken some time for decision makers to recognize that facility maintenance is crucial to the educational mission. While the university’s facilities department has been documenting capital renewal needs since 2000, “we did not get much traction,” says Boyce, “until we brought in a third-party consultant to review our facilities operation relative to effectiveness compared to other institutions that have similar facilities and programs.”

The consultant’s review identified that Carleton was not properly funded for renewal upkeep of the campus buildings and infrastructure in order to keep pace with its competition. After the data were presented to the university board, trustees approved an additional $14 million per year for 10 years to tackle the maintenance needs. “We see the funding of renewal, which includes deferred maintenance, as a high priority to improve the academic experience as well as student success,” Boyce says.

Diverse Funding Sources

On many campuses, the costs for needed maintenance are not just daunting, but downright overwhelming. But at campus after campus, leaders are finding ways to access funding for their projects.

State funds, foundation grants. For instance, Rhode Island College, Providence, was missing out on extra state funding for maintenance, because it wasn’t always following the state’s preferred approach for requesting funds. “We went to meet in person with state decision makers, and found out the exact format for our requests,” says David Gingerella, vice president for administration and finance at the college. “Once we started sending proposals in the preferred format, we started receiving money. And we now give regular updates, so that state officials know that we are spending funds in the way they intended.”

In addition to seeking more state funding, Rhode Island College has also applied for and received a number of grants from The Champlin Foundation, a community foundation that supports nonprofit organizations in Rhode Island. For instance, in 2015, the foundation awarded the college $375,000 to renovate a biology teaching laboratory, and in 2017, the college has applied for a grant of $455,550 for a major renovation of an instrument room and two chemistry teaching labs.

Energy savings contracts (ESCO). Other colleges and universities are taking advantage of energy services providers to help fund upgrades that result in energy efficiency improvements. For instance, Slippery Rock University in Slippery Rock, Pa., took advantage of Pennsylvania’s Guaranteed Energy Savings Act (GESA, a form of ESCO) to catch up on its deferred maintenance while advancing its sustainability initiatives, says Amir Mohammadi, chief financial officer and vice president of finance, administrative affairs, and advancement services. The GESA provides low-cost borrowing for energy efficiency projects and guaranteed savings, as it legally requires projects to generate positive cash flow through reducing utility costs in excess of annual debt service for the cost of the improvements.

For example, when Slippery Rock partnered with Honeywell to provide campuswide modernizations—including replacements of HVAC chillers, piping for steam and condensate distribution, and all the windows in three buildings—the project’s energy conservation measures accounted for $8.6 million of the university’s deferred maintenance needs. “Because the project produced such a high amount of energy savings, it allowed the university to bundle with it low energy savings items that addressed deferred maintenance while still keeping the overall program within the required thresholds of a 20-year payback and positive annual cash flow,” Mohammadi says. “The guaranteed aspect of the program requires these energy savings to be achieved and Honeywell Industries to write the university a check for the difference, if the savings are not realized. Most importantly, this program avoids the university having to commit its own resources to fund these projects.”

While Slippery Rock will continue annual spending towards deferred maintenance, the university will be able to clear more of its backlog, because this program will have addressed many higher priority projects. Before undertaking the energy savings project, the university identified $60 million in deferred maintenance projects—and with its annual budget of $2 million to $2.5 million for maintenance, realized that it would take 25 years to catch up. “The guaranteed energy savings program allows work that was slated for years in the future to be completed sooner, because the backlog has been reduced through the funding provided through this guaranteed energy savings program,” Mohammadi says.

Internal funds. In some states, legislatures and boards are pressuring colleges and universities to increase their budgets for deferred maintenance. For instance, last year, UMB was required by its board to increase its deferred maintenance budget by $1.5 million, but after Rhodes’ team began sharing with stakeholders its newly assembled data—complete with charts, graphs, and images—the university doubled that budget increase to $3 million per year for the next 10 years.

The University System of Maryland’s board just approved the creation of a quasi-endowment to be directed to deferred maintenance. When the fund is set up, monies will be diverted from UMB’s fund balance to become an ongoing source of funding for deferred maintenance projects, Rhodes says.

While many institutions are boosting their budgets to catch up with long-delayed maintenance projects, some also have cash reserves that are available to make a dent in the needs. For example, when he arrived at Rhode Island College, Gingerella found that some of the residence halls had not been updated to meet current building codes. “It seemed that the prior administration wanted to wait until the residence halls deteriorated to such a degree that they would need to be torn down and replaced with new buildings,” he says.“But those buildings were paid for. We did some digging and found that we had reserves available to upgrade and update them without any debt or new funding, and now they are preferred places for students to stay, rather than the new dorms.”

Tracking and Planning

As tackling deferred maintenance has become increasingly important for institutions and their funders, growing numbers of colleges and universities have developed complex systems for tracking their facilities’ needs, and planning upcoming projects. While some, like UMB, have hired outside consultants to develop robust and easily searchable databases, others have created their own proprietary systems.

At Johnson County Community College in Kansas, Rex Hays, associate vice president for campus services and facilities planning, has spent the past 11 years adding onto a lengthy, comprehensive spreadsheet that details all the building components on the campus. Hays also maintains a hard copy of the current list in a binder, and he and his team live by it. “You have to understand what your maintenance needs are,” Hays says. “We identify every component on campus, including buildings, roadways, and sidewalks. We know the life cycle of each component and perform maintenance based on that.”

Not only does Johnson County have a one-year, five-year, and 10-year maintenance plan based on the spreadsheet, but leaders also make certain to consider future maintenance needs in new building projects. “The same team is responsible for maintaining current buildings and constructing new ones, so they are very conscious about the maintenance for new facilities,” Larson says. “As we’re working with architects on two new buildings, we’re carefully reviewing designs and choosing materials to make sure the buildings work, not just for our students and staff, but also for the people who clean and maintain them.”

As a result, the two buildings now under construction will include easily maintained concrete floors, and exteriors that are mostly metal and precast concrete rather than masonry, which requires many repairs. In addition, Hays is involved with all the mechanical and electrical components, “intentional about their designs to ensure simplified maintenance later,” he says.

Planning ahead for new buildings is part of the growing trend to focus on getting ahead of maintenance rather than piling up more “deferred” projects. At UMB, the new standard for any new construction project is to factor in 2 percent of replacement cost for deferred maintenance within the new facility’s operations budget, Rhodes says.

Over the past 10 years, Clemson University, Clemson, S.C., has also created a “robust data warehouse” that includes information about all campus facilities and components, along with planned maintenance needs prioritized by category, says Brett Dalton, vice president for finance and operations. “We have a long-range plan looking at the campus 20 to 30 years out, and considering how we want to develop the campus,” Dalton says. “We start with that and, based on our growth plans, we turn that long-range plan into five- and 10-year specific, project-based capital plans so that we know all our major renovations and new construction projects.”

Clemson, like a number of other universities, partners with Sightlines, a facilities benchmarking and analysis company, to help leaders make educated decisions about facilities investments. “Sightlines comes in and does a comprehensive review of all the buildings and benchmarks the results against those of other facilities locally and nationally,” says Gingerella, who used the service in his former post at Northern Essex Community College in Haverhill, Mass. “The benchmarking allows leaders to show their boards or legislators where their facilities are falling behind those of their competition or neighboring states.”

Achieving Buy-In

When Gingerella arrived at Rhode Island College in April 2017, he asked how many roofs were scheduled to be replaced that summer. The answer: None. Next, he asked how many were replaced last year. The answer was the same. And how many roofs were leaking? Many.

“I said, ‘We have 43 buildings, and if a roof is good for 30 or 40 years, doesn’t it make sense to start replacing one every year? By the time we’re finished, it will be time to start over at the beginning again,’” Gingerella says. “When I explained it like that, everyone agreed it made sense, but it was just different from the way maintenance had been viewed in the past.”

For Rhode Island College, it was a matter of reframing maintenance as a regular, expected cost rather than an afterthought or an emergency when allowed to get out of hand. The college ended up replacing four roofs during the summer of 2017, and more are on the way.

Accurate, regular, engaging data are crucial for getting leaders on board with the need for deferred maintenance projects, says Clemson University’s Dalton. On his campus, deferred maintenance is a “dirty word,” because the university views all maintenance as planned maintenance, which is scheduled and funded in advance.

However, that wasn’t always the case. “There was a time when maintenance was not a high priority,” says Dalton, who, after his hiring in 2007, uncovered an aging electrical system dating back to the 1950s and 1960s. “A snake on a transformer or a squirrel stepping on the wrong wire could cause an entire campus outage,” he says. “One of my goals was to change the model and make maintenance an expected, regular budget item.”

Using detailed data and regular communication, Dalton has helped do that. “Every year, we present audited financial statements looking at the condition of the university from a dollars and cents perspective, but we typically don’t do that in a meticulous fashion for our capital assets,” he says. “We need to give our boards a rigorous, data-driven report on the condition of our capital assets, as well as the importance of those assets to providing education. I believe good people make good decisions, but we have to educate them in operating in a regular, data-driven manner.”

As a result of detailed annual reports on Clemson’s capital assets, Dalton has seen the attitude toward existing capital assets “totally change,” he says. “Maintenance tended to be an afterthought; people thought, ‘We’ll fix it when it breaks.’ Now we’ve had a total change in philosophy to protecting and enhancing what we have.”

Similarly, at Johnson County Community College, clear, engaging data have been vital to funding maintenance needs. “A few years ago, coming out of the recession, we were not fully funding our deferred maintenance backlog, and that’s when you start getting behind,” Larson says. “But board members understand facilities—they are business owners and homeowners. We showed them graphs depicting the ages of our buildings and images of what would happen if we didn’t keep them maintained; and they were very supportive of our needs.”

NANCY MANN JACKSON, Huntsville, Ala., covers higher education business issues for Business Officer.