“Faculty and administrators in most universities come together daily to accomplish a variety of tasks. However, we do not often perceive ourselves to be ‘collaborators.’ Frequently, we encounter each other as adversaries, bound to represent our distinctive groups and monitor the behavior of the ‘other side.’ Thus, we focus on negotiating compromise rather than on collaborating to create the most effective solutions.”

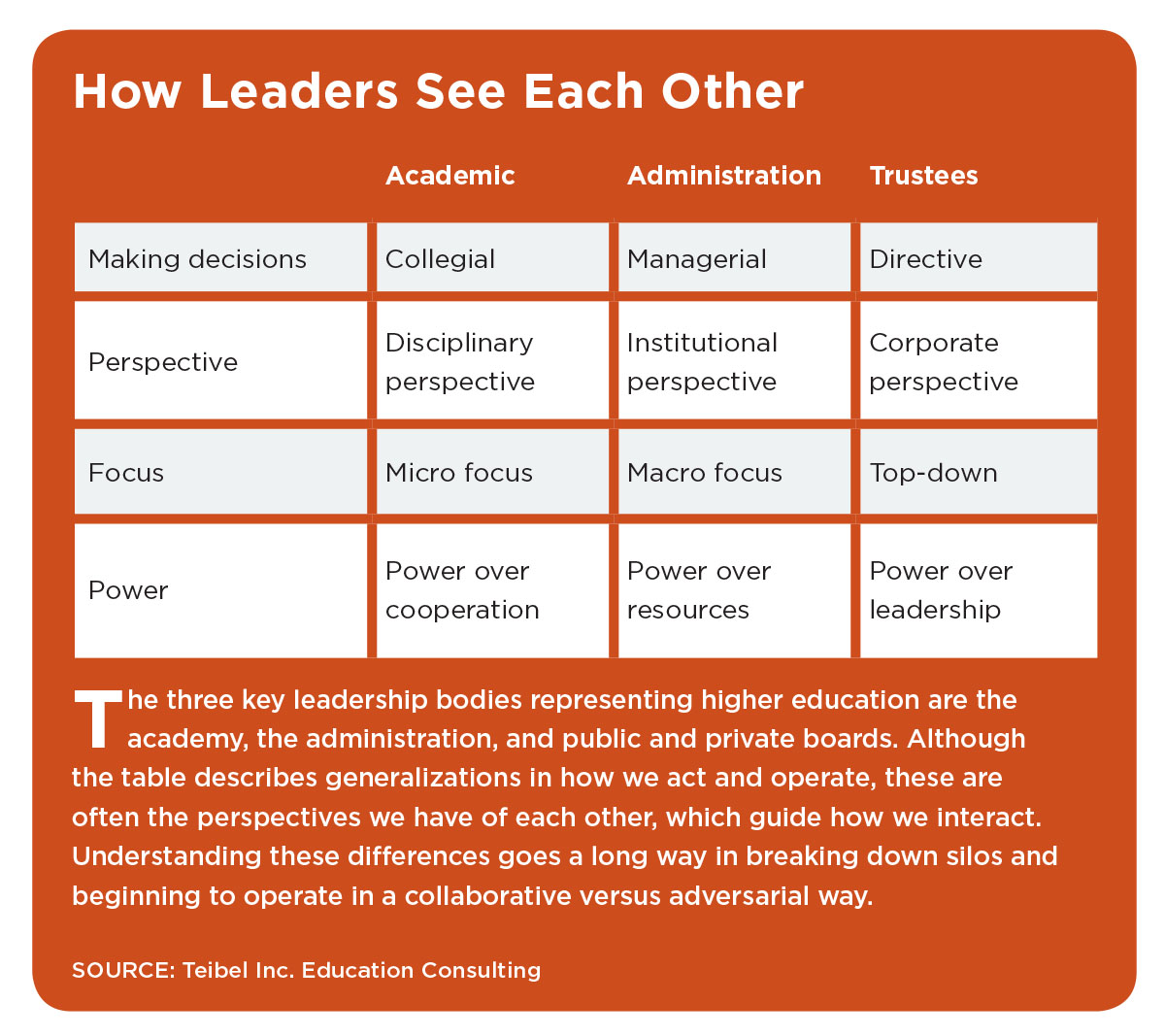

These comments from Linda McMillan, former provost of Susquehanna University, Selinsgrove, Pa., exemplify a frequent perception by administrators of their academic colleagues and vice versa. Whether myth, fact, or partial truth, collaborating “across the aisles” is a challenge in any higher education institution, and it means taking the time to understand the needs of those working in completely different disciplines and functional areas. Underlying every role in an academic institution (including that of the CBO) is a tie-in to the larger mission, but this often gets lost in the day-to-day grind.

“In my view,” says Russell Moore, provost and executive vice chancellor, University of Colorado Boulder, “our mission, as a major research university, is twofold. We exist to serve our students by providing them with opportunities for the types of intellectual and social development that will position them to be productive and personally fulfilled participants in our society. We also exist to promote scholarly inquiry and fundamental research and discovery, and, as such, we assume a critically important role in our nation’s social and economic vitality.

“Collaboration among units that we typically think of as being academic and nonacademic provides the institution with a huge opportunity to align the whole organization to the core mission of the university. While every university employee owns responsibility for and contributes to the university’s mission, not every employee understands his or her role in that way. Meaningful collaboration promotes that type of understanding. Every groundskeeper, budget analyst, HR professional, faculty member, student, and office staffer should take pride in the fact that great creative work, student success, scientific discovery, Nobel Prize, or inspiring performance associated with the university would not be possible were it not for their collective efforts. Promotion of that understanding of common mission serves to mitigate the ‘us vs. them’ mentality, which in turn translates into a more productive and purposeful campus community.”

The practice of shared governance is ultimately the mechanism that strengthens the institution’s ability to get things done. For example, such a collaborative process at Loyola University Maryland, Baltimore, resulted in strong support for some difficult decisions.

Stephen Fowl, chair of the theology department served as co-chair of this campuswide review, along with Terrence Sawyer, vice president for advancement at the university. Fowl explains how President Brian Linnane addressed the university’s financial challenges and the need to streamline processes, develop efficiencies, and cut costs. Linnane initiated the “New Way of Proceeding,” a process for gathering broad input to shape revenue-generation ideas and make tough cost-cutting decisions.

The design and process for this initiative was co-developed by Loyola leadership and Teibel Inc. Education Consultancy. It called for soliciting recommendations from across the campus through 12 working groups populated by volunteers from faculty, staff, administrative, and student communities.

On a quarterly basis, the groups presented the recommendations to a central steering committee, which in turn distributed them to the entire campus community; the Loyola Conference (a governing body focused on the budget and strategic planning); and the Academic Senate. Anyone could provide an opinion, raise questions, and express approval or disapproval. The Loyola Conference and the Academic Senate were not voting bodies; but they made their recommendations to the president, along with an indication of “high concern,” “some concern,” or “low concern.” The president grouped the ideas into four categories: accepted, accepted with modifications, delayed because of timing, and rejected. The various vice presidents responsible for implementation then discussed the final accepted recommendations.

Although this was a time-consuming process, it received enormous buy-in. As a result, says Fowl, when future decisions had to be made—such as the elimination of some positions (and associated personnel), and cuts in employment retirement packages—the shared experience of the New Way of Proceeding made it much easier for the bodies across campus “who had built up a storehouse of good will and leadership” to work together on the latest strategic plan decisions.

Although this was a time-consuming process, it received enormous buy-in. As a result, says Fowl, when future decisions had to be made—such as the elimination of some positions (and associated personnel), and cuts in employment retirement packages—the shared experience of the New Way of Proceeding made it much easier for the bodies across campus “who had built up a storehouse of good will and leadership” to work together on the latest strategic plan decisions.

George Martin, president of St. Edwards University, Austin, puts it succinctly: “Honoring shared governance is about reminding all of us that the board has primary authority and part of its role is to delegate important matters of university life to faculty and senior leadership. There is nothing I can think of in university life that does not involve faculty and staff input. But, while everyone should have a voice, only some have a vote, and even fewer have veto power.”

At the same time, attaining an effective level of shared governance can be challenging and sometimes elusive—very much like the complex dynamics around effective strategic planning (for more on collaborative strategic planning methods, see “It Takes a Campus” in December 2015 Business Officer). How can we encourage and implement ways to move past the obstacles to reap the benefits?

As officers of your institutions, what is your role in affecting this change? Regardless of how your campus currently administers shared governance, the goal is to build on that process by beginning to open critical conversations to improve on existing governance practices. The risk of not developing a healthy shared governance model is that decisions will rest with the individuals who have the legal authority to make them. The following explanations and examples show the rewards of getting governance right.

Three Guiding Principles

As a practitioner and thought leader on the topic, Richard Chait, professor emeritus at the Harvard Graduate School of Education, suggests that shared governance rests on three principles:

- Consultation—the opportunity to express one’s views.

- Communication—the opportunity to be updated and informed.

- Explanation—or a commitment to convey the rationale behind decisions.

“At the heart of these three methods is the principle of transparency or having clarity around who gets to make the decision and then communicate the rationale,” says Chait. Further, he explains the way that governance relates to each group.

The academy: Conducts formal decision making around programs, hiring, and other fundamental academic activities.

The board: Has a fiduciary and legal responsibility in governing the institution. Its role is to ensure faculty are part of the process.

The administration (led by the president or chancellor): Interprets the right balance of engagement from boards and faculty.

While the academy may view shared governance as an end in itself, the office of the president, with support of the internal leadership body, works through shared governance as a means to an end.

When conducted properly, there is a healthy tension built into this governance model, similar to our country’s model of the executive, legislative, and judiciary branches, which ensures that no one branch can run away with the keys and take the institution down a wrong path. While such measures prevent one body from having all the authority, they can slow down decision making.

A current area of tension, for example, is the focus on “financial sustainability”—the new mantra for the business office. Boards are being asked to step up and govern more aggressively to address the financial and legal challenges facing their campuses, while more administrators are looking at the academic model to try and understand the cost structure of programs. Faculty are increasingly concerned that their influence in these conversations is diminished, as institutions look more to the bottom line than to the underlying mission. As questions of profitability only grow, many faculty sense the shift away from teaching and research for its own sake.

As a result of these tensions, there has never been a stronger need to bring parties to the table and quell often-ungrounded fears that boards and administrators are attempting to turn our premier institutions into professional or technical schools. A shared vision needs to be articulated across academic and administrative functions so that each role can contribute to the overarching mission.

Kelly Fox, senior vice chancellor and CFO at University of Colorado Boulder, works closely with Provost Russ Moore on many initiatives. “We are very intentional in ensuring that we maintain open communication across the academic and administrative areas,” she says. “My partnership and regular meetings with the provost are key in making sure he meets his goals while understanding their financial implications. When we make it a priority to understand each other’s needs, the business side more naturally takes care of itself.

“We’re also collectively responsible for meeting the needs of research, teaching, and student success. It’s the synergy across our divisions that drives our ability to do that. We won’t thrive without this mindset.”

Amir Rahnamay-Azar, vice president for finance and CFO, explains such a coming together at Carnegie Mellon University (CMU), where the president and provost have embraced a vision to catalyze a powerful “innovation corridor” in Pittsburgh, with the university leading the way. Their vision builds on the demonstrated success of university faculty, students, and staff to create and advance innovative disciplines, programs, and industry partnerships, and to drive economic growth.

The innovation corridor—anchored along Forbes Avenue—represents new opportunities for researchers and students; a more interconnected physical environment; significant economic opportunities for the region and university; and a strengthened network of intellectual partnerships spanning the globe in science, technology, and the arts. Rahnamay-Azar explains that CMU is pursuing the development of a new mixed-used facility (the Gateway Project) on university-owned property as a critical component of this vision. The Gateway Project will be a strategic anchor for innovative activity on Forbes Avenue, serving as the gateway to CMU’s main campus.

To explore this opportunity, Carnegie Mellon engaged a cross section of board of trustee advisers, university academic and administrative leaders, subject matter experts, professional consultants, and focus groups in an inclusive and iterative process to garner the best result for the university.

With this vision in place, the CFO leads thorough and collaborative evaluation, analysis, and due diligence, in partnership with subject matter experts and professional consultants.

The university is also broadly engaging campus stakeholders, deans, and other key members of academic and research leadership, and members of university leadership via several working committees to inform and drive the programming and transactional structure of the Gateway development to maximize the benefit to its faculty, researchers, and students.

Since the vision was announced, the board of trustees, through its audit, finance, and properties and facilities committees, has been involved. Committees have held regular meetings in which members receive updates on the university’s progress and provide leadership with meaningful feedback and perspective on this critical strategic initiative. Periodic updates are also provided to the board’s executive committee and the full board.

Since the initiative to develop the Gateway project was first introduced, the university has conducted more than 250 meetings and working sessions, including close to 1,000 campus stakeholders, city and state officials, neighbors, and industry partners. From program and site analysis, to concept validation, proposal evaluation and financial modeling, the university has thoughtfully considered all aspects of the project, and deliberately taken the time to solicit feedback and to develop a thoughtful evaluation that considers both qualitative and quantitative measures for data-driven decisions.

In the coming months, working committees will review the final proposal for the Gateway Project; the leadership will consider the proposal for approval; and, if approved, the plan will be presented to the board for authorization.

When and How Joint Decisions Apply

All the interviewees with whom we spoke—regardless of the role in their respective institutions—emphasized that a key step to joint decision making and shared governance is to first determine what decisions rightly belong to each of the individual bodies at an institution. An unintended consequence of this lack of clarity can be turf wars and cases of inappropriate overreaching by one body into areas that are truly owned by another.

Some of these primary areas of responsibility are easy enough to identify. For example, questions about the university’s financial health and assets live with the board, curricular design remains with the academy, and internal human resource policies are handled by the administration. It is wise for institutions to articulate in a detailed manner the primary roles and responsibilities of the three main bodies at their own institutions.

Once the roles are identified, it is helpful to determine some of the overarching responsibilities that should be left to joint decision making. Areas such as long-range institutional planning, the formulation and modification of general education policies, budgeting, and the selection of a president are best left for collaboration. While it is unlikely that the leadership is able to identify all institutionwide issues upfront, achieving a general understanding of the primary vs. shared issues helps reduce ambiguity and confusion, and smooth the path for all decision making on campus.

In the spirit of driving collaborative decision making, when groups come together to decide on policy or institutional priorities, three questions can guide the dialogue:

1. What problem(s) are we trying to solve?

2. Why is it important to solve them?

3. If we were successful, what would the resolution or new state look like?

Too often collaborative decision making skips over these three critical questions and instead leaps directly to “what do we want to do?” We make many assumptions about our shared understanding of the importance of a decision and often want to check the box to move forward. Doing so often cause us to address the symptoms versus root cause of the problems, or divert our attention to issues that are not truly mission-critical.

From Principles to Action

Behind shared governance is a set of principles that Chait’s earlier comments describe: communication, consultation, and explanation (or transparency).

- Communication. Mary Davis, recently retired board chair at Mt. Holyoke College, South Hadley, Mass., and member of AGB’s Commission on College and University Board Governance, notes: “Communication is the No. 1 issue in shared governance. No matter how many rules and forums bring them together, people need to be informed about what they need to know, and given opportunities to give input for reviewing, revising (or hybridizing) the particular plan. Only then can the institution effectively implement a plan.

“The most important thing is to maintain dialogue between the constituencies. It builds respect and trust. It gets away from a ‘gotcha culture,’ and creates more alignment with the vehicles and communications that allow the discourse to happen across the constituencies.”

At Mt. Holyoke, leaders facilitate effective dialogue in several ways.

Leading together. President Lynn Pasquerella formed a joint leadership council, composed of faculty, staff, and administrators, to meet monthly to share information and to cross-hatch activities and initiatives for alignment to the execution of the strategic plan. The council also formed the foundation for broader cross-campus cooperation on a number of issues—from the role of online graduate programs to the implementation of “innovation hires” to accelerate new curriculum development.

The work of the council has smoothed the operations of faculty committees, which have planning and budget responsibilities, and made the alignment with the college budgeting process more transparent and more collaborative. The dean of the faculty now works with the CFO and the faculty planning and budget committee to study and recommend budget changes.

Other positive outcomes of the council include improved communication across campus on a number of issues, including: (1) the evolution of transgender admissions policy, (2) diversity and inclusion on campus, and (3) the decision to build a new community center that offers dining and other services. The ability to work from a level playing field of cross-constituency understanding of priorities and challenges has been most beneficial in making progress in these areas.

Inclusive planning. The strategic planning process, which is now underway, is fostering communication and participation across all constituencies: faculty, administration, board, students, and alumnae. This process at the full-committee level, and also at the sub–task force level, is promoting sharing of information, data, market trends, and so forth, across the participant groups.

This strategic planning process is the best example of future thinking and consideration as to what is best for the institution. This future context and focus provides a safe place for more forward-thinking conversations about change. While still in process, the strategic planning groups are all working well together. For example, two sub–task forces focus on academic departmental evolution and on organizational structuring of alumnae relations and advancement.

- Consultation. A critical need exists, says Chait, to educate all bodies on campus about each group’s responsibilities and their boundaries, while providing opportunities for everyone to present their views and sides of the story. What is the difference between fiduciary responsibility and the practice of faculty, administration, and student inclusion? Launching an educational initiative on shared governance and decision making, as a dialogue will leave all parties with a greater understanding of the appropriate role of each body and a deeper appreciation for the current state of how governance is implemented at the institution.

Governing in this collaborative way demands an openness on the president and cabinet’s part to treat shared governance as a learning exercise as much as a set of rules or principles. A willingness to be transparent is an important first step but more importantly, encouraging people to come to the table with genuine questions about roles and responsibilities across all roles can set an important tone for building a new model for sharing decision making.

Transparency is demonstrated by an initiative at the University of Colorado Boulder, says Fox, “that focused on institutional inequity that existed in the way we allocated budgets through our merit pools process. When I sat down with the provost, we discovered that academics handled it in one way and administration another. We noted differences in the way we counted individuals, how we distributed the budget, and so forth.”

As a result, Fox and Moore created a joint working group of academics and administrators to evaluate the merit pool and establish a new process for the next fiscal year. “For the first time,” says Fox, “we had leaders from across the institution sitting down together and learning how each had historically approached the problem of merit allocation—and to collectively envision a new future, ultimately being willing to let go of the old ways of doing things.”

- Explanation. St. Edward’s University President George Martin, in response to a distributed faculty survey, took the opportunity to organize a Shared Governance Task Force, made up of three board members, three faculty, and three administrators. “Dialogue is educational, and education affords the opportunity for consensus. The goal of this task force was to clarify the meaning and process of shared governance and explain the respective roles of the faculty, the board, and the administration. At its first meeting, the task force reviewed AAUP and AGB documents and developed a set of guiding principles. The faculty members of the task force proposed an agenda for all upcoming meetings, and it was accepted. This gave us a foundation on which to build agreement and recognize the role of faculty in shared governance.”

Events or Activities to Build on Shared Governance

“Take advantage of events to launch shared governance, such as when a new president comes in, or when a new board chair is appointed,” says Mary Davis. “It’s simpler to focus on improving shared governance when there is a significant change or something that represents a new direction for the institution, than it is to try to wrestle the ship around and layer shared governance on top of a set of pre-existing, less-than-constructive relationships.”

While changes in leadership or other universitywide initiatives can be a basis for developing collaborative efforts, the use of a strategic plan can be a valuable tool to practice shared governance and provides a formal way for aligning the efforts of all the bodies for the good of the entire institution.

At the University of Colorado Boulder, from the chancellor on down, the leadership embeds three goals across the campus, explains Fox. “We call them the three Rs: revenue, reputation, and retention (or student success). That third goal is founded on the idea that we must meet students where they are.” Last year, explains Fox, administrators reimagined the student success goal in a way that led to a “Student Welcome” initiative led by the student affairs division. Significant involvement of faculty, administration, the registrar’s office, and admissions resulted in changing what was a two-day event into a series of podcasts and online experiences for incoming freshmen. “We engaged them in ways we’d never done before,” says Fox, “and the new welcoming techniques were a complete success.”

Collaborative thinking. From October 2014 through October 2015, Carnegie Mellon University undertook a comprehensive and rigorous effort to plan for its future. “In developing our Strategic Plan 2025,” explains Rahnamay-Azar, “almost every part of our Pittsburgh campus, our global locations, and our larger community around the world were touched. Faculty, staff, students, alumni, and university leaders joined together in town hall meetings, strategy retreats, and planning sessions.”

- In doing so, the university was able to identify a number of key goals:

- Become a destination of choice for innovation and entrepreneurship.

- Model leadership in research and creativity.

- Facilitate an interconnected network of research and creativity.

- Develop a concentration of world-class talent.

- Build a culture of interdisciplinary approaches to problem solving.

- Exert regional impact.

The Gateway Project described earlier will further the university’s strategic plan by developing an “ecology” of infrastructure to promote and support excellence in CMU’s research, creativity, innovation, and entrepreneurship endeavors, and catalyze interdisciplinary encounters among faculty, staff, students and alumni. CMU’s vision is to be the academic destination for faculty, staff, and students seeking a culture of innovation and entrepreneurship with opportunities to learn, conceive, collaborate, launch, and lead in new endeavors. This project is a transformative development not only for the university, but also for the region.

Intentional shared principles. A positive shared governance experience is tricky because it involves authentic communication, rising above politics, and getting groups that speak a different language to come together and appreciate each other’s contribution. Shared governance asks difficult questions about who is responsible, who should be engaged, and how does the institution ensure that governance doesn’t get bogged down in dialogue. The model has great strengths when administered with transparency, good will, and a willingness to educate and engage all parties. The bigger question for each person is, “Do we have the will to interact in honest dialogue to understand how each entity views the challenges and goals in an effort to listen to concerns about representation.

Kelly Fox puts it this way: “Shared governance has many dimensions in which every leader must become invested. As business officers and partners with academic leadership, it is our responsibility to make sure presidents are in the best position possible to educate and inform the board and faculty about key issues and their respective financial implications. When shared governance is working well, the majority of stakeholders understand how decisions are made and are appreciative of the transparency the leadership provides.”

HOWARD TEIBEL is president of Teibel Inc. Education Consulting, Natick, Mass.

Exceptional Group Decision Making. Creating a culture adept at group decision making is one of the great leadership challenges. It requires alignment in the face of personal stakes on the team, political motivations, individual belief systems, and ego. It requires individual contributors to have a keen ability to listen, and an even deeper ability to dig into a key question that people almost never ask, but may be the most important question for team processing:

Exceptional Group Decision Making. Creating a culture adept at group decision making is one of the great leadership challenges. It requires alignment in the face of personal stakes on the team, political motivations, individual belief systems, and ego. It requires individual contributors to have a keen ability to listen, and an even deeper ability to dig into a key question that people almost never ask, but may be the most important question for team processing: