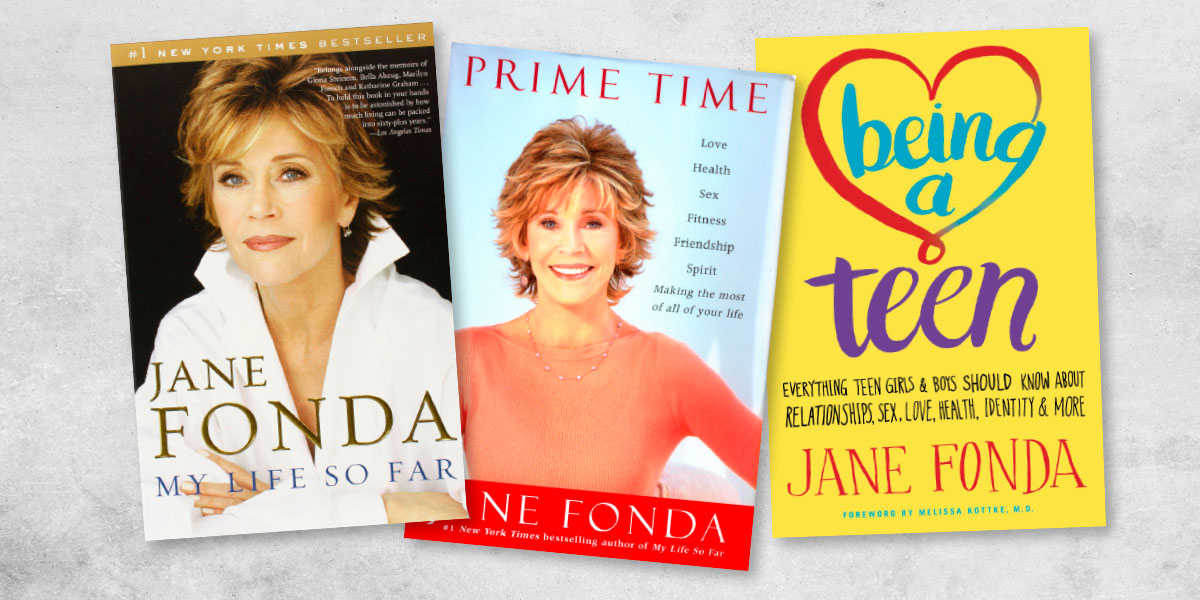

Known first for her roles as a fitness guru, activist, and Hollywood actress, Jane Fonda is now a frequent speaker on youth development, women’s issues, and the longevity revolution. In 2005, she published her memoir, My Life So Far (Random House), which became a New York Times best-seller.

Since then, Fonda has published Prime Time (Random House, 2011), a comprehensive guide to living life to the fullest—particularly beyond middle age—and Being a Teen (Random House, 2014), an all-encompassing guide to adolescence.

Fonda’s latest film, Book Club, hit movie houses in mid-May. She’s also starred in recent films, such as Our Souls at Night, This Is Where I Leave You, and Lee Daniels’ The Butler, and currently stars in the hit Netflix series Grace and Frankie.

Outside of acting and writing, Fonda focuses heavily on activism and social change. She is the founder of the Georgia Campaign for Adolescent Power and Potential, as well as the Jane Fonda Center for Adolescent Reproductive Health, at Emory University School of Medicine. She also serves on the boards for Women and Foreign Policy at the Council on Foreign Relations; the Women’s Media Center, which she co-founded in 2004; and V-Day, a global activist movement to end violence against women and girls.

In an interview with Business Officer, Fonda offers a preview of her remarks at the NACUBO 2018 Annual Meeting, in Long Beach, Calif., July 21–24.

Having revolutionized the fitness industry, become a best-selling author, starred in numerous films and other productions, all amongst activism and social change, how have you managed these various roles and traditions? Where do you find the energy to continue this high level of productivity?

No. 1, I’m born with a lot of energy. It just comes naturally. No. 2, I make a point of sleeping eight or nine hours every night. And, No. 3, I take care of myself, so that I’m healthy. It’s hard to do any of these things if you’re not healthy.

But, also, I love what I do. I love my work as an actress. I love the research needed to write books. And I love the issues that I support as an activist. I’m inspired; I love learning; and, I love teaching. All of that keeps me energized.

Where do you think the ability to take a risk and seek out new ventures comes from? And, what can others do to open themselves up to more options and be willing to break new ground, as you have?

Truthfully, I don’t know. Everybody is very different, obviously. For me, I reached a point in my early 30s, when I knew that I’d rather die than to lead a meaningless life. The most frightening and sad thing I can think of is to come to the end of my life—when it’s too late to do anything about it—and to feel that I haven’t made a difference in some way.

Now, making a difference, it can mean raising fantastic, healthy, productive children. It can mean doing things for your community. It doesn’t have to be big and global. But, just knowing in your heart that you are leaving the world a little better, because you were there in some small way, is important to me. And, when I see something that I feel is really, really wrong—that kind of makes my hair stand up on end—then I just want to scream. Because, I think, “This can’t be. This is just too horrible.” I’m willing to do just about anything to change it, to stop it; and I’ve been that way for a long time.

Now, again, I don’t know why exactly I’m that way. I grew up on the sets of my Dad’s pictures, like Grapes of Wrath, The Oxbow Incident, and Twelve Angry Men. Those films were about people who really tried to make a difference. Maybe that has something to do with it; it probably did. And, then, it’s just part of my nature. But, I don’t know what might motivate others to be like that.

You write a lot about self-discovery in My Life So Far. As you say in the book, it’s about a woman who finally realized that she didn’t need to be perfect, and that good enough was good enough. She didn’t need to live up to other people’s standards. After coming to that conclusion, in what ways did you live your life differently? And, were there any benefits or losses to doing so?

Nothing but benefits. What happened was that I could exhale, I could relax and be more myself. Things didn’t upset me in the same way, and I could forgive myself more. And, I certainly could forgive other people more. I could just lighten up, which was important, because, I spent a lot of time in my life not being very light. I was like Eeyore for a long time, and I’ve kind of moved to Tigger’s corner.

You launched the Georgia Campaign for Adolescent Power and Potential when Georgia had the highest teen pregnancy rate in the country. What data can you share about the far-reaching outcomes of reducing the number of teen births?

The issue of teen pregnancy has such a large impact on education. When a girl gets pregnant, she often drops out of school because it’s too hard to manage as a single parent. First of all, most of the children who have babies before they’ve grown up and formed a firm partnership with the father or mother of their child are poor. Middle-class kids tend not to have babies out of wedlock, when they’re very young, because they know that it will compromise their future—and because they do see a future for themselves.

Poor kids don’t think about or see any future, so, there’s really nothing to compromise. Why not have a baby? They sometimes think: at least it’s something that will love me, something that will make me seem and feel like an adult. They don’t have any motivation to use contraception or to delay being sexually active. So, we’re talking about kids who are disadvantaged in the first place.

On top of that, if they get pregnant and then drop out of school that puts them at even greater disadvantage. If you mapped out the pockets of poverty in the United States and then overlay them with the pockets of high rates of teen pregnancy, those areas will overlap.

As I traveled the state, I saw how ignorant these children were about how their bodies work. I think middle-class people would have a hard time understanding the complicated circumstances that surround early sexual activity and early pregnancy. It’s a very complicated issue.

When I married Ted Turner and moved to Georgia, I learned that the state has a very high rate of adults who have not graduated from high school, nor gone to college. High rates of poverty exist particularly in the southern part of the state. So, one thing that we’ve done to reduce teen pregnancy rates is to train teachers to teach comprehensive, age-appropriate sexuality education. It’s generally not easy for adults to talk about these issues that our culture considers to be a moral issue, rather than a public health issue. In other countries that have very low teen-pregnancy rates and low abortion rates, people and society treat these as public health issues.

NACUBO represents higher education. How might educators and leaders see that more teens have access to education opportunities to enhance their lives?

As educators, we need to teach kids about how their bodies work, about how to avoid pregnancy, and—even more importantly—what a real relationship is about. The question people asked me most often was, “How do I know if it’s a real relationship?” Kids need to know what a relationship is supposed to feel like, and that it’s supposed to feel safe. If you can’t feel safe talking to your partner about sex and what you each expect from it—if you can’t talk about those things with your partner, then you’re not ready to have an intimate relationship with that person.

The feelings of safety, of trust—all these things need to be communicated and taught—since kids don’t know the essential parts of a healthy relationship.

We also have, across Georgia, “second chance” homes funded by the state, with assistance from the federal government. Teen mothers grow up and learn how to be parents, learn how to cook, and take care of children. And, then we help them get jobs afterwards. These are some of the things that need to happen in states with high rates of teen pregnancy. And, it was very, very moving to me to see the effects it can have on kids. It’s life changing.

One more thing: Hope is the best contraceptive. We have to give kids the hope that they will have a future so that they will want to think about how they’re behaving now, in ways that won’t compromise that future.

In a recent Town and Country interview, you noted that you often thought life could be better, and that you were motivated to move on, because you were “afraid of getting to the end of my life without becoming the best I can be as a person.” That may be one reason that led you to do a life assessment, what you call “excavating your life.” What did you learn from that assessment, and how has it changed your behavior?

I learned that there is a theme that goes through my life, even from early years. A theme of courage and honesty. And, I wouldn’t have known that if I hadn’t written that book, which I call a life review. As part of it, I interviewed friends, going back as far as my middle-school years. I discovered that I have been brave, had stepped forward, and owned my mistakes—and tried not to repeat them. So, I think courage is one leitmotif that runs through my life.

Learning about that gave me confidence, and that’s what really changed. It allowed me to more often stand up for myself.

The one place where I lacked courage was in my relationships with men. I was always trying to please, as opposed to standing up for myself. That began to change, too, after I wrote the book.

In Prime Time, you talk about the “Third Act,” and describe the idea of rehearsing your future and actually writing down the vision of the old woman you wish to be. What value did you find in that? How do you think that those entering their third acts—and that includes a high percentage of college and university CBOs who will be retiring within the next five years—might benefit from doing something similar?

I think it’s very important to do this. Most of us go through life afraid to think about the end, because we’re afraid of death. I clearly understand that; I don’t want to die. But, I’ve spent time in countries [where people] don’t have such a fear of death. This may be an exaggeration, but it seems that they’ve kind of made friends with death. It’s why Halloween—which is a foolish commercial holiday for us—is observed as a time of year in many other countries, including Mexico, to honor saints and family members who have died. People gather the family together; take along some bread, cheese, and wine; and go to the graveyard. They sit among the headstones, toasting and thinking about their ancestors who came before, who are now dead. It’s like the wall between life and death is much more permeable—and not so scary.

Because I admire that and think that it’s the healthy way to live, I realized that, if I didn’t think about how my life would end up, I might be swept away like a leaf in a stream, rather than being the oar in a stream, steering a boat and managing the currents.

Forgiveness, for example, became very important to me. I don’t want to die without forgiving the people that I need to forgive, and asking them for their forgiveness. And, for forgiving myself. I don’t want to reach the end of my life without the people who are closest to me loving me. Which means I had to earn that love and make amends, say more often that “I love you,” and express my love more and more robustly.

This carries down, for example, to the way I want to die and be buried. I’ve made it very clear to my children that I don’t want to be cremated or put into a casket, because it’s bad for the environment. I want to be put into a biodegradable pod, which now exists.

I’ll be buried in a cemetery in Santa Monica, where Tom Hayden, the father of my children, is buried. There’s this huge field of native, drought-resistant, California grasses—no tombstones, no headstones, no nothing—simply people in the ground and flowers and grasses growing on top of them. And, my children know that I want to be put there, where Tom is, because then they don’t have to go to two different places when they want to commune with us.

That’s a beautiful idea. It leads me to ask about your description in your book of Eric Erikson’s idea of generativity, and how it relates to spending part of our third act as advocates for the future?

Generativity; it’s like recycling. I feel that part of the responsibility and joy of the elders in our society, of which I am one, is to mentor and nurture the young people coming up. Mostly by example. And, by wanting to reach out and help in different ways.

For me, here in California, the most profound and beautiful example of generativity is Father Greg Boyle’s work. He founded Homeboy Industries, in south central Los Angeles, which has saved the lives of hundreds of thousands of former gang members—boys and girls—and turned them around by the programs that he started. They run businesses; they get their tattoos removed; they manage a great bakery; and they even have access to health care. He has saved so many individuals and deserves to be honored with sainthood, in my opinion. That’s a perfect example of generativity.

In a way, on a much more individualist level, Katherine Hepburn was an example. When we were making On Golden Pond together, she was very intentional in the way she taught me lessons. She realized that I had to overcome my fear of learning to do a backflip, which I had no intention of doing—until she challenged me. She said that it’s important to confront your fears. Otherwise, you’ll get soggy. She taught me a number of other things, very explicitly, while we were working together.

I wrote in Prime Time about the concept that old people are like arches—very resilient forms of architecture. While our youth-obsessed culture encourages us to focus on the arch as a symbol of physical growth and decline, Rudolf Arnheim, late professor emeritus of the psychology of art, at Harvard University, suggested another metaphor that we can choose: the stairway. That image points to late life’s promise, even in the face of physical decline. As I wrote in the book: “Perhaps it should be a spiral staircase! Because the wisdom, balance, reflection, and compassion that this upward movement represents don’t just come to us in one linear ascension; they circle around us, beckoning us to keep climbing, to keep looking both back and ahead.”

EARLA JONES is senior director, annual meeting, NACUBO.