On Nov. 1, 2016, in an effort to facilitate the “borrower defense to repayment” process, the Department of Education (ED) published final rules providing student loan borrowers a more transparent course of action when filing claims.

The department undertook the rulemaking following the closure of Corinthian Colleges, when ED received an influx of borrower defense claims from former Corinthian students.

The same regulatory package also introduced new financial responsibility requirements for independent nonprofit and for-profit institutions that participate in federal student aid programs. Public institutions backed by the full faith and credit of their states are not held to the current or new standards of financial responsibility.

The final rules are slated to take effect on July 1, 2017. However, it is possible that the Trump administration and Republican-controlled Congress may take action to block this and other regulations promulgated in recent months by the Obama administration.

Republican leaders are examining their options to roll back a number of Obama administration actions and policies, including use of the Congressional Review Act. This law enables fast-track action by Congress to overturn major regulations issuedafter May 30, 2016, by federalagencies. The Trump administration could also decline to carry out the regulations,or Congress could prohibit the Department of Education from applying any resources to enforcement.

Republican Party priorities for 2017 clearly include rolling back federal regulations, but it is too early to predict what President-elect Trump’s priorities for higher education will include, and whether this regulation might be targeted for reversal. Nonetheless, institutions of higher education should familiarize themselves with the new rules.

During the development stage of the regulations, NACUBO argued that the borrower defense rulemaking process was not the appropriate venue to add to its current financial responsibility rules. However, ED disagreed, and ultimately included the changes as part of a final effort by the Obama administration to protect student loan borrowers and promote greater institutional accountability.

Borrower Defense

In its August 1 comment letter, NACUBO supported ED’s goal to establish borrower defense standards and define the evidence that former and current students must provide to show that a college’s misconduct warrants debt relief, but also expressed some concerns with certain borrower defense rules and limitations. Ultimately, the department made few changes between the draft and the final regulations. The new regulations create a standard for making debt relief available to students when there is:

(1). A breach of contractual promises between a school and its students.

(2). A state or federal court judgment against a school related to the loan or the educational services for which the loan was made.

(3). Substantial misrepresentation by the school about the nature of the educational program, the nature of financial charges, or the employability of graduates.

NACUBO understands ED’s desire to regulate false and misleading marketing, but remains concerned that “the vastly broadened view of misrepresentation will result in a booming business for lawyers and will tie up institutions in governmental red tape.” ED argued that the fallout from Corinthian’s closure necessitated expanding on the previous definition.

Under the final regulations, there is no statute of limitations for discharge of borrowers’ loan balances still owed or relief based on state or federal court judgments. The statute of limitations is six years for borrower claims—based on misrepresentation and breach of contract—to recover payments that have already been made on loans that originated on or after July 1, 2017.

The final regulations also establish a process to make it easier for the department to provide relief to groups of borrowers. NACUBO supported this plan in its comment letter.

ED also established a number of additional new protections, including a ban on the use of pre-dispute arbitration agreements by institutions to avoid class action and individual law suits.

Institutional Accountability and Financial Responsibility

For 20 years, private nonprofit and for-profit institutions have had to show that they are not at risk of precipitous closure, using a financial responsibility calculation based on three ratios that produce a composite score. Depending on the score, some schools are deemed financially responsible, some fall into the “zone alternative” and are subject to additional oversight, and schools with failing scores are subject to provisional certification and must post a letter of credit in order to continue to participate in the Title IV programs.

Using the borrower defense to repayment rulemaking process, ED has introduced a set of triggering conditions that could lead to a recalculation of an institution’s composite score, and, if warranted, require it to provide financial surety to ED and publicly disclose certain information to current and prospective students. Institutions experiencing a triggering event will be required to notify ED, in most cases, within 10 days.

NACUBO and others have found that ED, under the existing rules, often fails to correctly calculate financial responsibility ratios for nonprofit institutions—and has been doing so for years. ED is imposing this new financial responsibility structure before taking steps to resolve the problems inherent in its current practice. This process will be further complicated by recently released changes to nonprofit accounting standards.

Rules, Triggering Events, and More

The following is a summary of the final rules, triggering events, and consequences:

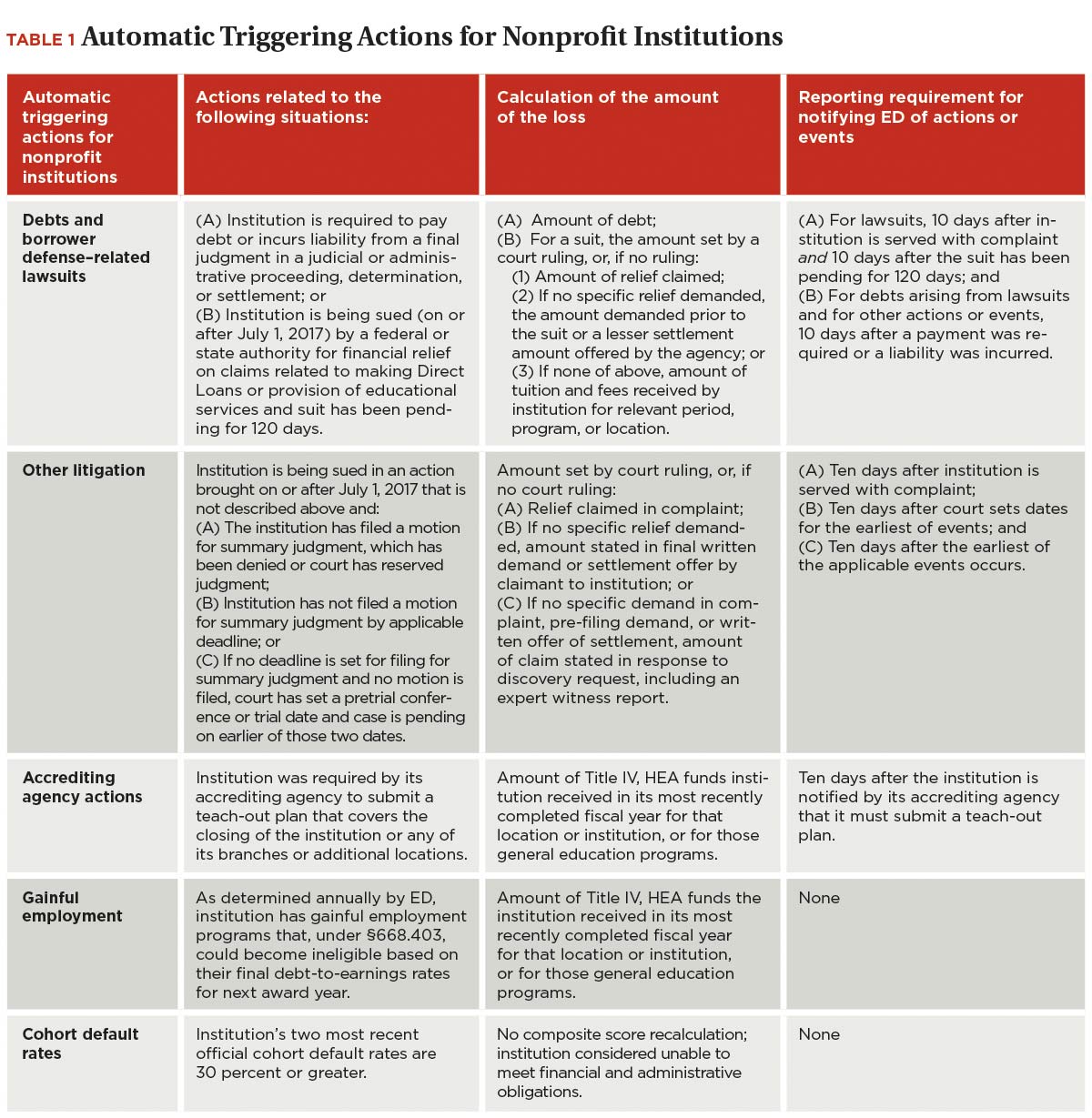

Automatic triggers. For nonprofit colleges and universities, a triggering event in one of four major categories results in the recalculation of the institution’s most recent composite score, unless the institution demonstrates—to the satisfaction of the secretary of education—that the event or condition has had or will have no effect on the assets and liabilities of the institution. In addition, any school whose cohort default rates for the two most recent years are 30 percent or higher will be deemed unable to meet its financial or administrative obligations. Several additional triggers apply only to for-profit schools.

ED will use actual or potential losses associated with the actions or events to recalculate the institution’s most recent composite score. “Automatic triggers” that would result in a recalculated composite score include:

(1). Debts and borrower defense–related lawsuits.

(2). Other litigation.

(3). Accrediting agency actions requiring teach-out plans for closing institutions, branches, or locations.

(4). Gainful employment program(s) that may become ineligible for the next award year based on final debt-to-earnings ratios. (See Table 1 for additional details.)

NACUBO is particularly concerned about new composite score recalculations resulting from borrower defense–related lawsuits and other litigation. As explained in the final rules, ED’s formula will increase total expenses and distort both the primary reserve ratio and net income ratio in the composite score calculation; the combined diminished ratios affect 60 percent of the composite score.

Under the formulas used to recalculate composite scores as a result of accrediting agency actions (teach-out plans) and failing gainful employment programs, potential losses will reduce revenue and only the net income ratio will be impacted.

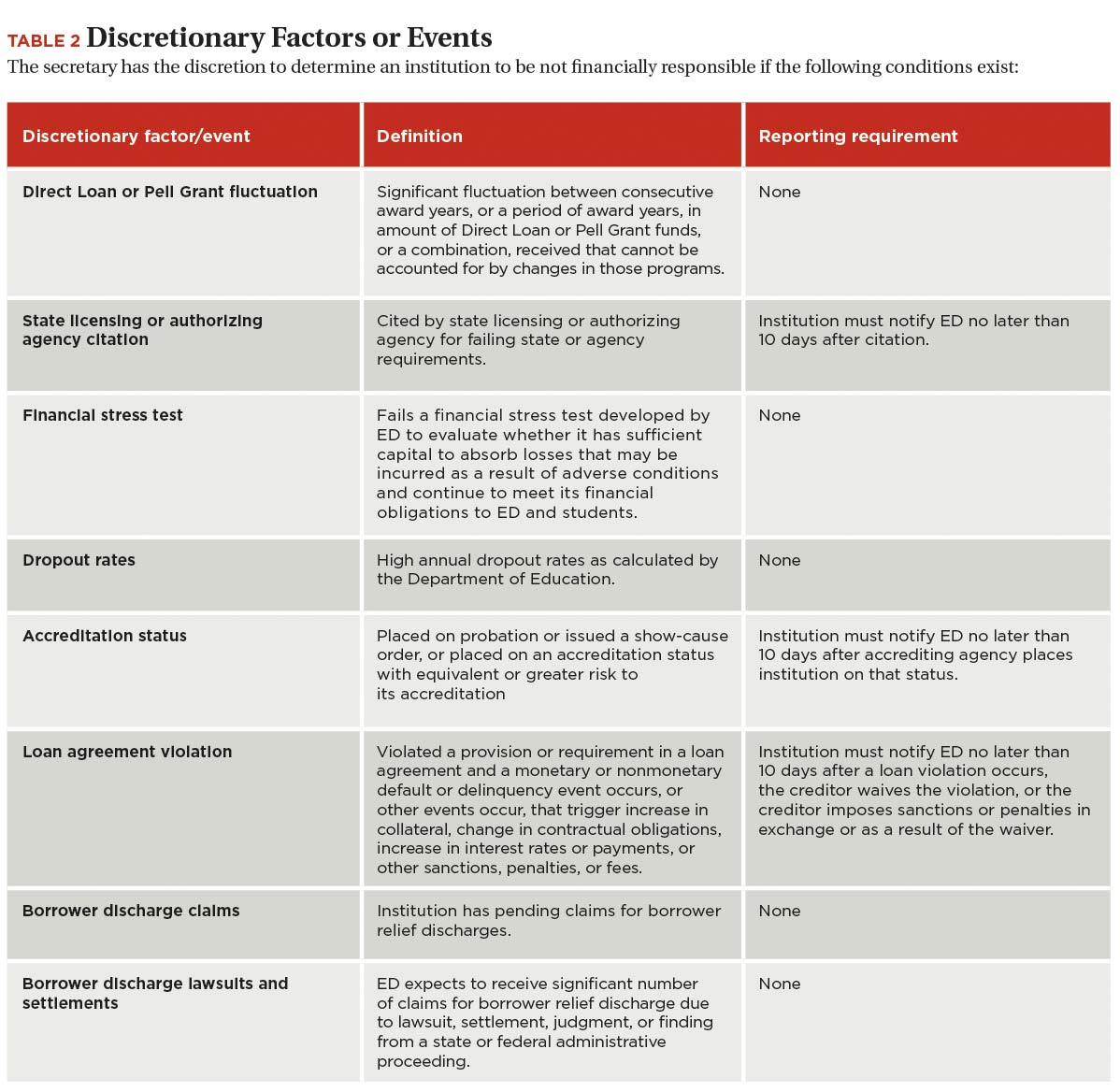

Discretionary triggers. The final rules also lay out a number of “discretionary triggers” that may lead the secretary to determine that an institution is not financially responsible. These include such indicators as (1) fluctuations in federal grant or loan utilization rates; (2) high dropout rates; (3) citations by state agencies; or (4) violations of agreements with creditors. These triggers do not lead to a recalculation of the composite score, but are considered on their own. Institutions might be required to participate in Title IV student aid programs under the zone or provisional certification alternatives and to post a letter of credit or other surety. (See Table 2 for additional details.)

Reporting and disclosure of information. ED proposed, in the draft regulation, that any school that is required to provide financial protection, must disclose that fact to current and prospective students as well as on the home page of the institution’s website. NACUBO objected strenuously to this provision, concerned that such a warning will drive away students and alarm potential donors.

In response to the concerns expressed by NACUBO, the department stated: “We understand the concern regarding the potential for the financial protection disclosures that were initially proposed, as well as the financial protection disclosures in these final regulations, to damage an institution’s reputation. However, we do not believe that the possibility of harm to an institution’s reputation is reason enough to withhold from students, who in many cases have borrowed heavily to finance their educations, information on the financial viability of the institutions they attend.”

The final rule backed away from the full disclosure requirements but states that, through consumer testing, the department will determine which triggers require a disclosure that is meaningful to students. It is unclear exactly how ED will proceed with consumer testing at this time.

Resources

For more information on the new rules, including expanded tables detailing the mandatory and discretionary triggers, read the article “ED Establishes New Financial Accountability Rules for Private Institutions” on the NACUBO website at www.nacubo.org.

In early 2017, NACUBO will provide additional analysis of the final rules.

NACUBO CONTACT Liz Clark, director of federal affairs, 202.861.2553, @lizclarknacubo