As budgets continue to tighten, university research parks are increasingly viewed as important vehicles for building additional revenue streams. But significant financial investments are required to create the facilities that will attract leading researchers and partnering corporations. Without the cash or wherewithal to develop the land and build new facilities, many universities look to outside partners for help. (Read also, “Research Parks Redux,” in April 2016 Business Officer.)

When a university seeks a partner in developing its research park, it has a number of options, including for-profit developers; nonprofit foundations; and, in some cases, land speculators and alumni investors. Because every park is different, every partnership agreement is unique.

Partnership Proliferation

For instance, when the Georgia Institute of Technology (Georgia Tech), Atlanta, wanted to expand its research programs but couldn’t access state funds for a research building, it partnered with the University Financing Foundation Inc. (TUFF), a nonprofit operating foundation, to design and build the Technology Square Research Building. That building, which opened in 2003, is now the cornerstone of Tech Square, a preeminent urban research park.

To complete the project, TUFF worked with a for-profit partner, so the building is jointly owned by the two organizations. Thirteen years later, Tech Square has attracted 14 different corporate innovation centers and is home to companies such as Home Depot, Coca-Cola, Delta, Anthem Healthcare, AT&T, Panasonic Corp., and Southern Co. “Tech Square produced the perfect storm of space for the university and its corporate partners,” says Kevin Byrne, president and chief operating officer at TUFF. “Companies want smaller spaces to have greater interaction with students and faculty. In the plaza, you see students, professors, millennials, baby boomers, Xers, everybody—operating, living, and working together. We are managing that serendipitous interaction.”

Learn From Others’ Experience

Not every university is prepared to work well with outside partners. Here are four tips for establishing effective collaborations in developing, redeveloping, or expanding a university research park or innovation center.

- Create a vision. While outside collaborators can bring strong ideas, to build an effective partnership, university leaders must start with a clear vision of the type of research park or facility that will best suit the institution. “When working with a university, we long for an executive leadership vision, not just ‘we want to create a research park,’” Byrne says. He advises university leaders to understand the needs of their current corporate partners and to develop a list of “aspirational partners” as well, with an understanding of how those particular organizations work and what they need from the institution.

“The vision looks different for everybody, based on land limitations and research interests,” says Byrne, “but you must have a vision to create the interactions that you want among students, faculty, researchers, corporate partners, and others. Think about how you and your development partner can create a place that will facilitate that future.”

- Understand your options. Selecting an outside partner often comes down to economics. A nonprofit partner is likely to share a university’s goals of education, research, and economic development, but may require the use of university credit to construct facilities. In return, the nonprofit partner may help reduce exposure of university credit by helping identify the kinds of building tenants that fit the university’s mission.

For-profit partners, on the other hand, are likely to finance the project themselves, but universities will have no voice in the types of tenants that may rent space in the buildings. Choosing between the two options depends on university priorities and other projects, and determining the most appropriate way to utilize financial resources, Byrne says.

- Consider unique partnerships. Every research park is different, and various types of partnerships work for various needs. A university may need a traditional for-profit investor, a nonprofit development foundation, or simply an expert consultant. “In many cases, we help provide guidance and equipment for the university to do things on its own,” Byrne says.

For instance, when Clemson University, Clemson, S.C., partnered with BMW to develop the Clemson University International Center for Automotive Research, it turned to TUFF to help with the planning stages. TUFF developed a business plan and a working model for the 250-acre automotive research park, and Clemson and its partners took it from there. After the park launched successfully, TUFF worked with its leaders on subsequent development.

- Take a long-term view. Today, universities are finding that research parks and economic development are powerful ways to create additional streams of revenue. In the future, there may be other more appropriate uses of university property. That’s why many universities structure their agreements with outside partners as long-term ground leases.

A number of building projects at university research parks are built on land owned by the universities, with an agreement to return the property, including buildings, to the university after a set number of years. For example, a typical TUFF project is designed and built on university land to the program requirements of the institution. The university leases the buildings or subleases them to other partners for 30 years; and at the end of the lease, TUFF conveys the building back to the institution.

Universities can often accomplish more by working with a partner to create or improve their university research parks. But to make those partnerships work well, university leaders should determine their own expectations upfront. “Universities see the need for research parks, economic development, and the creation of revenue,” Byrne says. “And the right partner can provide a place for the institution to bring together research, academia, and industry for collaborative environments and innovation.”

SUBMITTED BY Nancy Mann Jackson, Huntsville, Ala., who covers higher education business issues for Business Officer.

Like many institutions across the country, Pittsburg State University, Pittsburg, Kan., grapples with resources. During the late spring 2014 semester, staff members made a suggestion regarding the university’s summer schedule, as part of the strategic planning task force campus hearings. A modified summer work schedule could possibly build campus morale in today’s atmosphere of diminishing resources.

The strategic planning council then forwarded the concept to the president’s council for support. However, the provost’s leadership council and other administrative units provided feedback that the change would be difficult to effectively implement at such a late date.

To keep the momentum, campus officials agreed that a task force, made up of staff from business and academic units, would further study modified summer work schedules during fall 2014, and subsequently make a recommendation to the president’s council for a summer 2015 implementation.

A Deliberate Review

The group spent more than two-and-a-half months researching options. During the first phase of its research, the task force undertook a data review of existing summer schedules and past course offerings on campus—including building utilization—and conducted conversations with people representing all employee groups. It also reviewed existing schedules for institutions within the state, institutions in the same athletic conference, and those campuses that are close geographically.

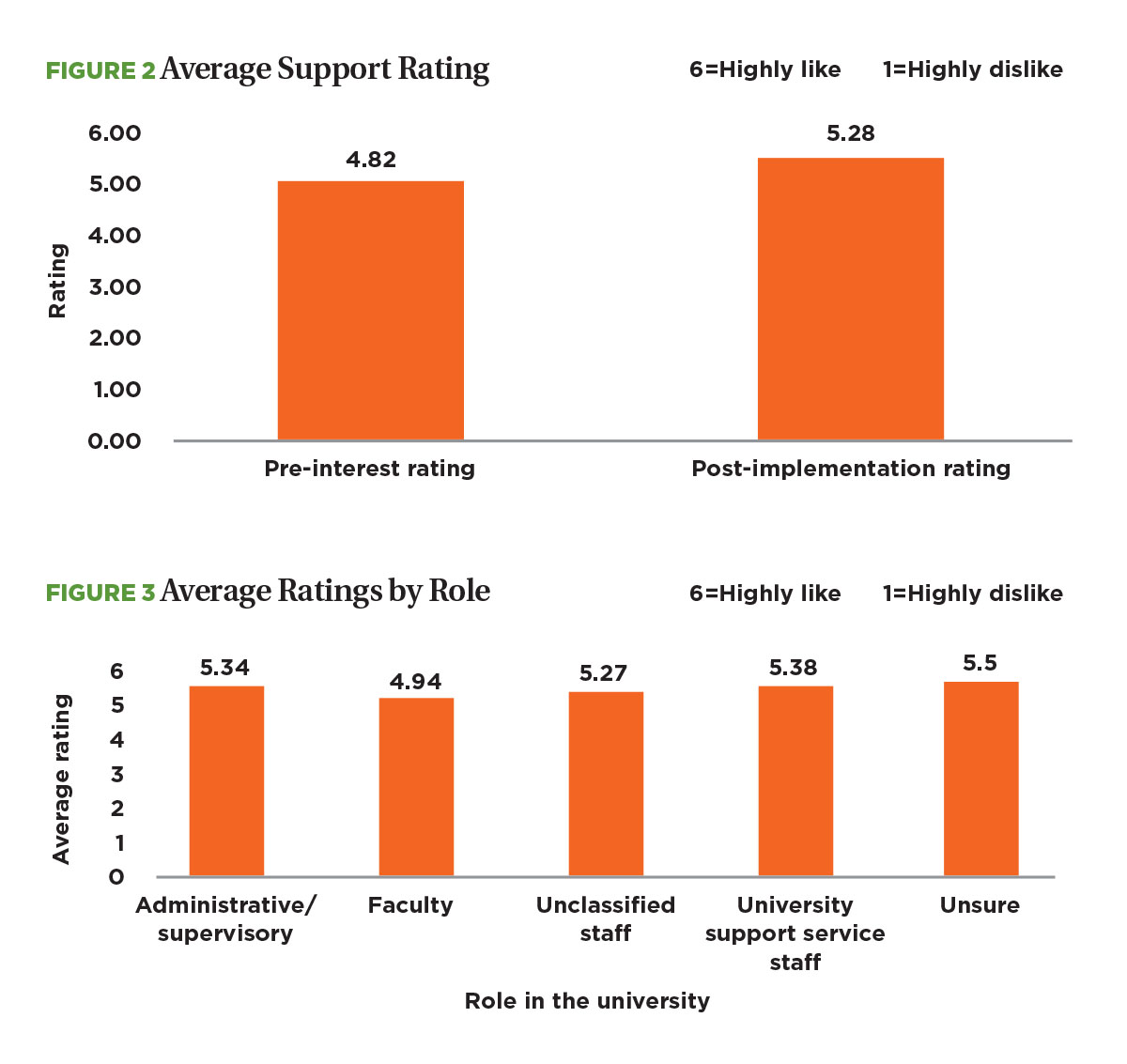

The group considered several options, including extended hours for a four-day workweek and flexible work schedules that met general office hours. As a result, the task force proposed a schedule concept that outlined regular office hours and developed a staffing plan that it presented to the campus for feedback.

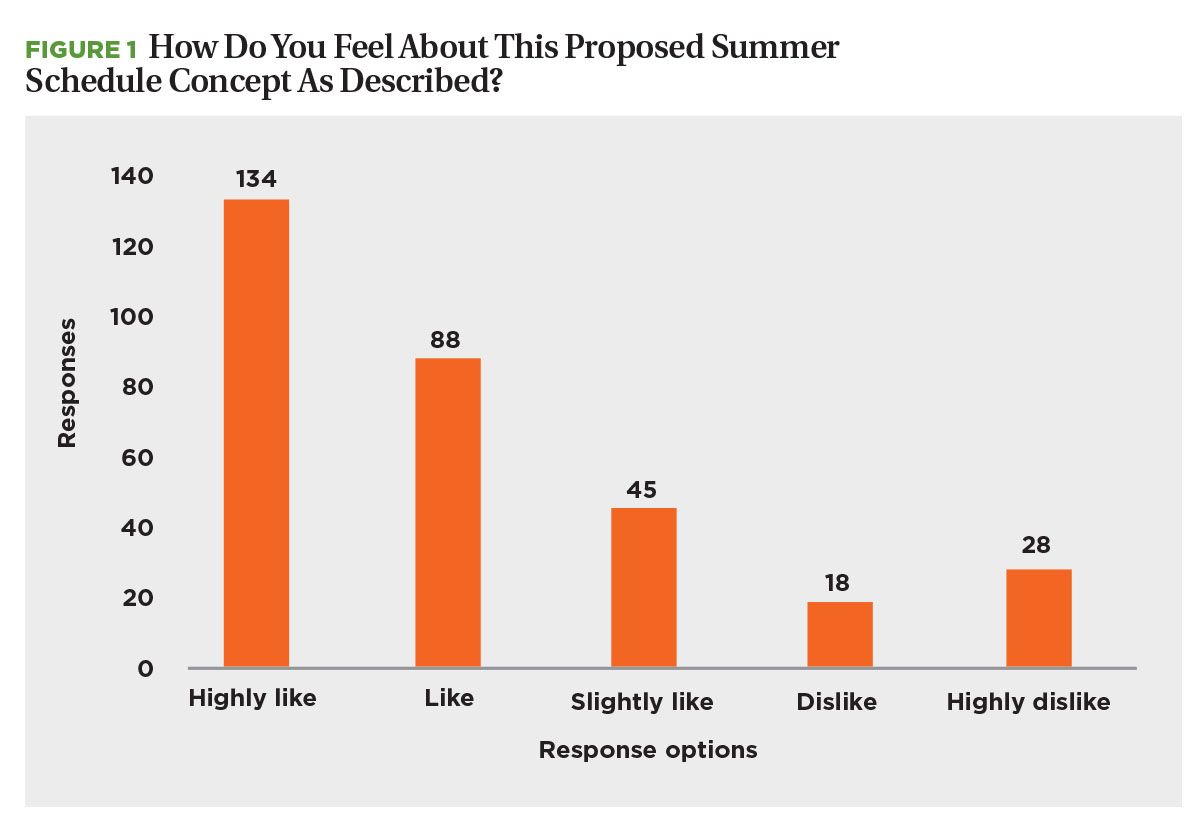

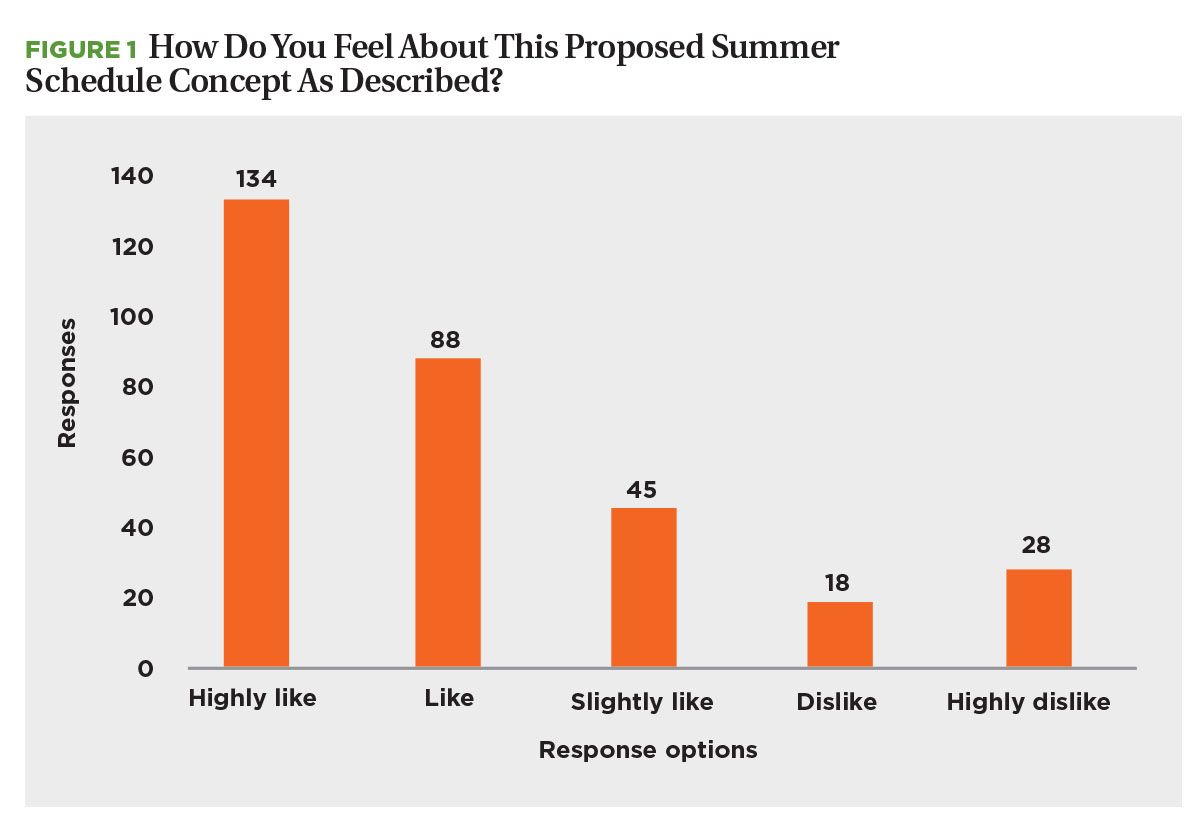

Next, we held three campus forums at varied locations and times to review data and provide as much opportunity as possible for valued in-person conversations. The group used the post-forum surveys as feedback (see Figure 1), which reshaped its proposal to reflect campus preferences for a summer schedule.

The final proposal was the scheduling of a four-and-a-half-day workweek, with two components: (1) maintaining regular office hours campuswide of Monday through Thursday, 8:00 a.m. to 4:30 p.m., with adjusted Friday hours of 8 a.m. until noon; and (2) each unit supervisor submitting a plan to the appropriate dean or director, indicating how the particular unit would maintain scheduled office hours while offering the flexible work schedule to its staff.

We implemented the plan in summer 2015, based on favorable responses to the concept. President Steve Scott said, “This is a great example of the power of open communication and the planning process. It’s an opportunity to provide our employees with a more flexible schedule without sacrificing service to our students or community.”

Results and Adjustments

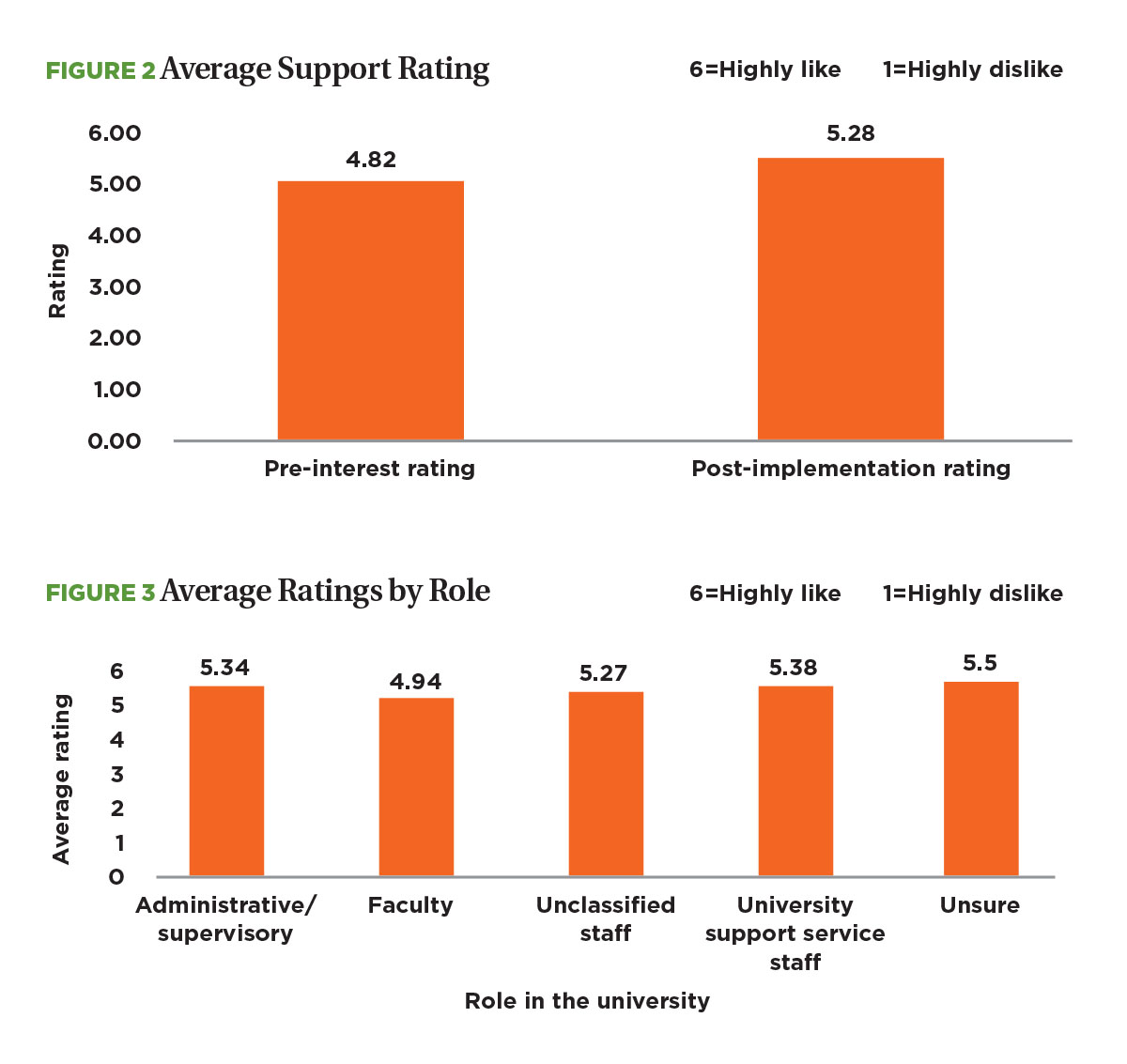

When the summer ended and staff returned for the fall semester, the task force initiated a post-implementation follow-up survey to learn what employees thought about the flexible summer schedule.

When asked if the schedule should continue the following summer, 90.4 percent of employees responded, “yes.” Answers to open-ended questions revealed that (1) most employees enjoyed the flexibility and extended weekends, considering them a good incentive; (2) several suggested a rotating schedule in which a different person covers Friday each week; and (3) clearer guidelines and more uniform hours across campus would reduce confusion.

Michele Sexton, director of human resources, notes: “Summer hours worked very well in 2015. We saw very few issues with employees on different schedules, including reporting hours worked and leave taken. HR staff enjoyed the flexibility as well, and it appeared that the rest of the campus also enjoyed the change.”

The details gathered from the survey serve as a basis for modifying and improving future plans for flexible summer work schedules, as part of a continuous improvement cycle.

Julie Dainty, then faculty senate president, says, “Having flexibility of hours for all individuals during summer operations seemed to increase overall morale. Adjusting to the variety of options was a learning curve, but I have heard many individuals already discussing with optimism their schedules for the coming summer. Personally, I feel a great benefit of the change was increased communication across campus.”

SUBMITTED BY Howard W. Smith, dean of the college of education, Pittsburg State University, Pittsburg, Kan.

Students, State Engage in Energy Talks

An educational event, “Power Dialog: Maine’s Energy Future,” held last month, engaged students, faculty, and staff at high schools, colleges, and universities throughout Maine in a weeklong discussion with state officials about the state’s energy and climate policy. Organized locally by Unity College, the University of Maine, and Maine Conservation Alliance, the Power Dialog is a nationwide, nonpartisan event aimed at bringing students face-to-face with officials in 30 states. Sponsored by the Center for Environmental Policy at Bard College, Annandale-on-Hudson, N.Y., the event focuses on what states can do to help meet the Paris Agreement (on climate change), without a legislative agenda, and without being an advocacy or lobbying project.

Showcasing the Path From High School to College

Merit recently announced the rollout of free accounts for more than 28,000 high schools in the U.S., enabling school officials to see, share, and promote the everyday outcomes of each of their alumni at colleges and universities nationwide. Since launching in 2013, Merit, which partners with colleges and universities that use its platform, shared those updates with high schools via a free weekly e-mail digest. Now, in addition, the digests will link to a free Merit account that is customized for every high school in the country. Principals, guidance counselors, and other administrators or teachers will be able to log in and see stories about former students’ current success at college.

![]()

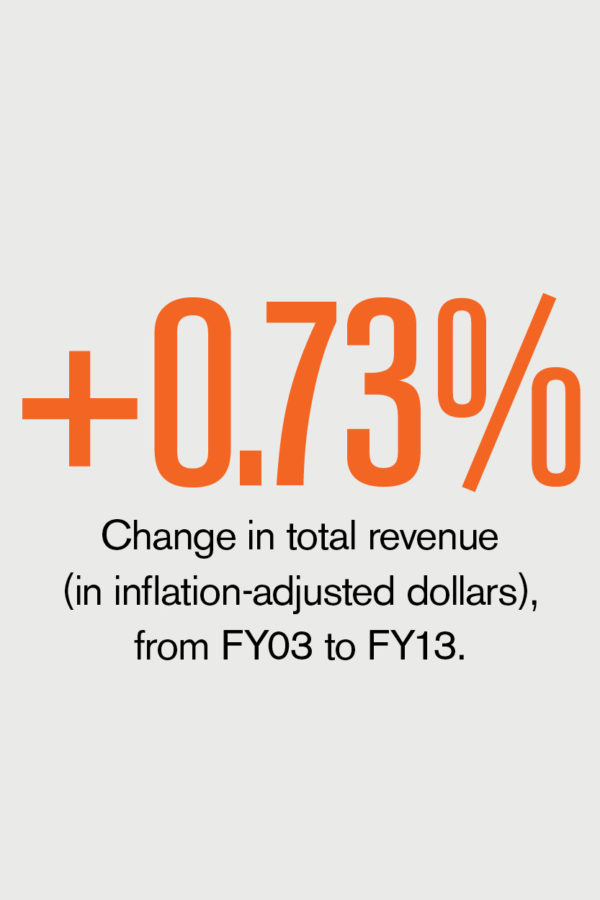

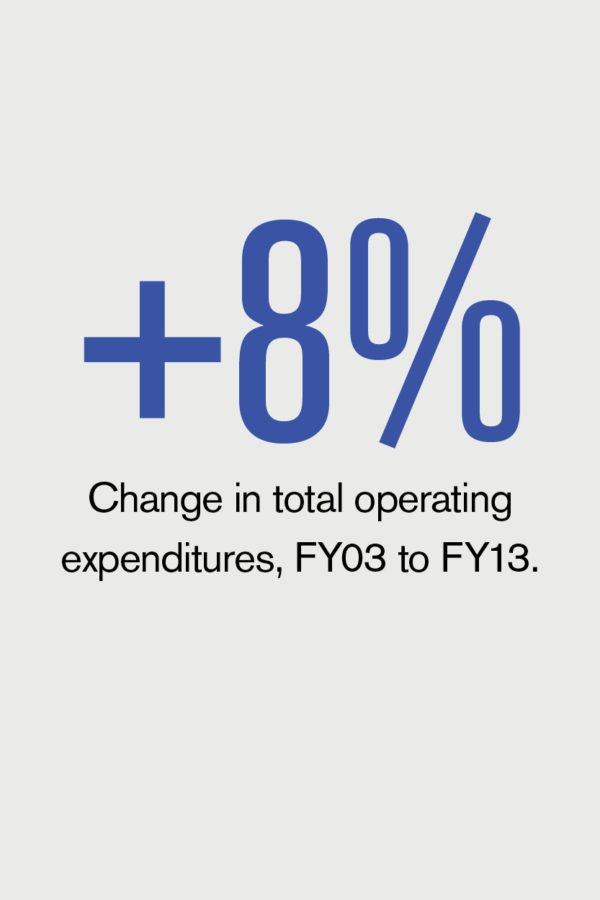

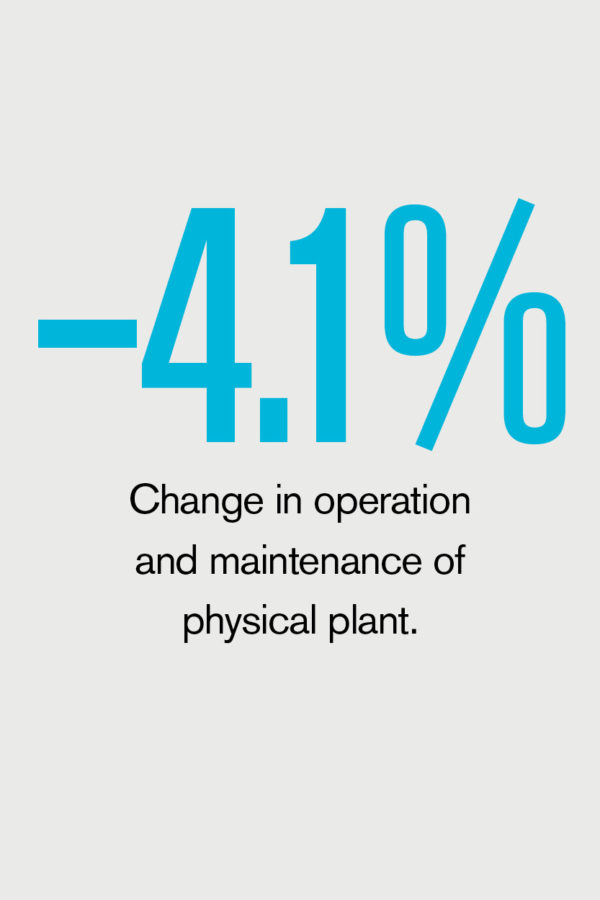

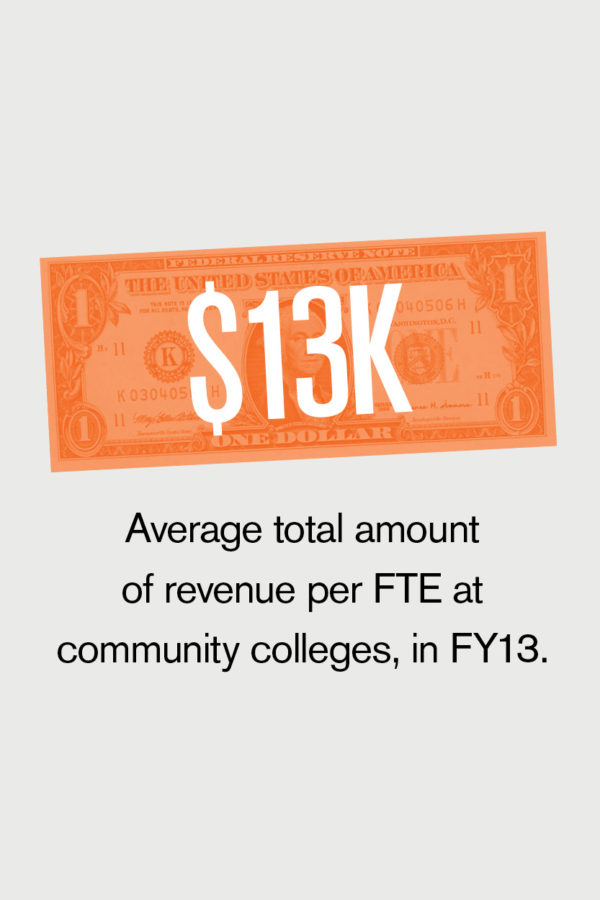

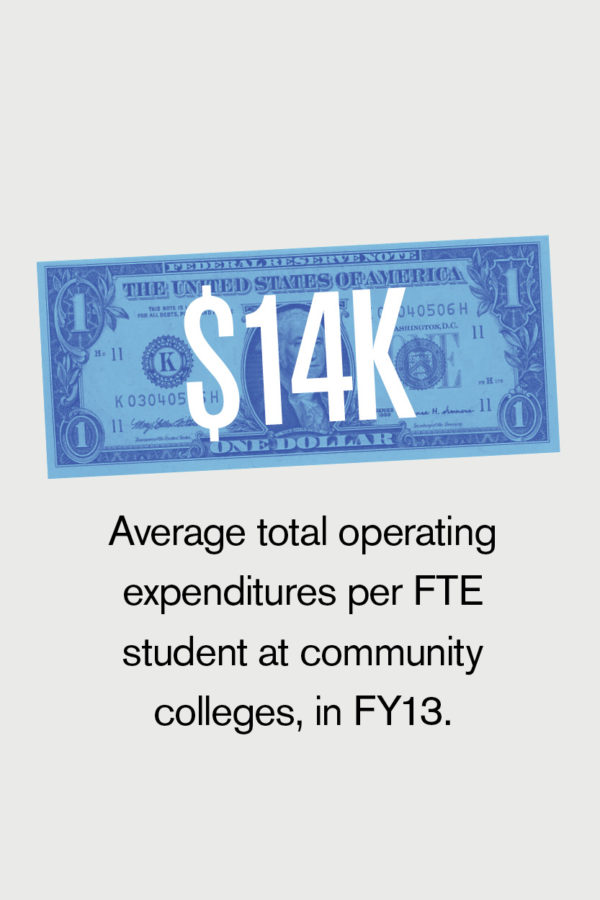

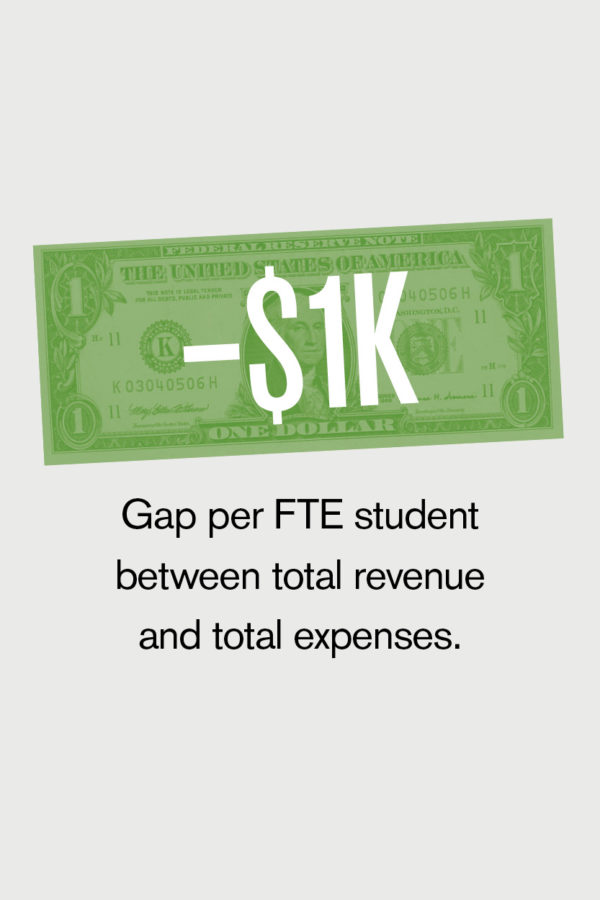

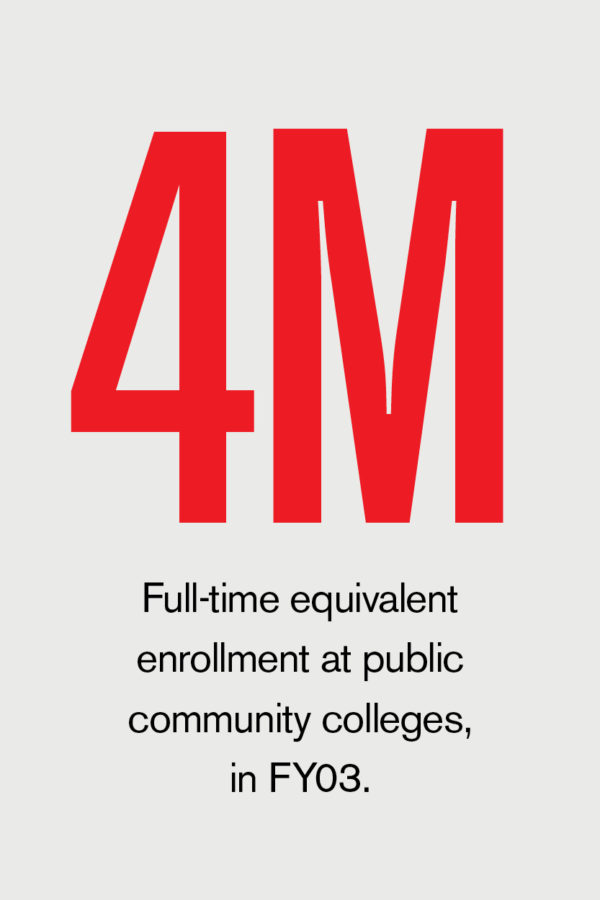

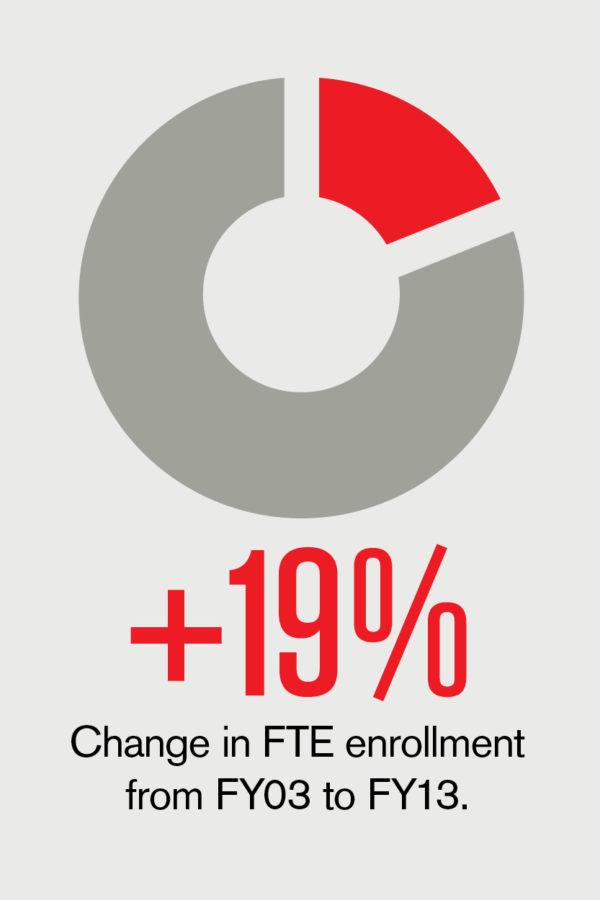

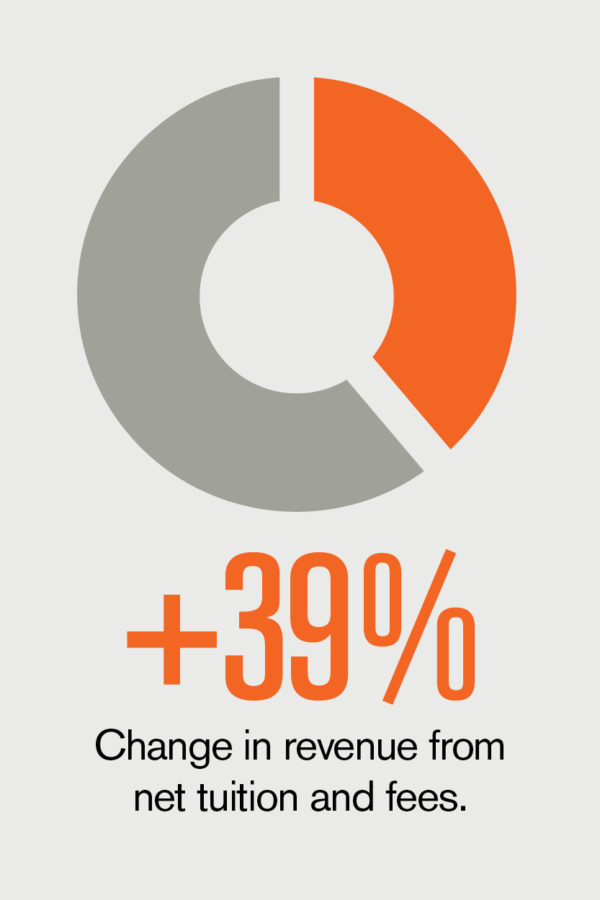

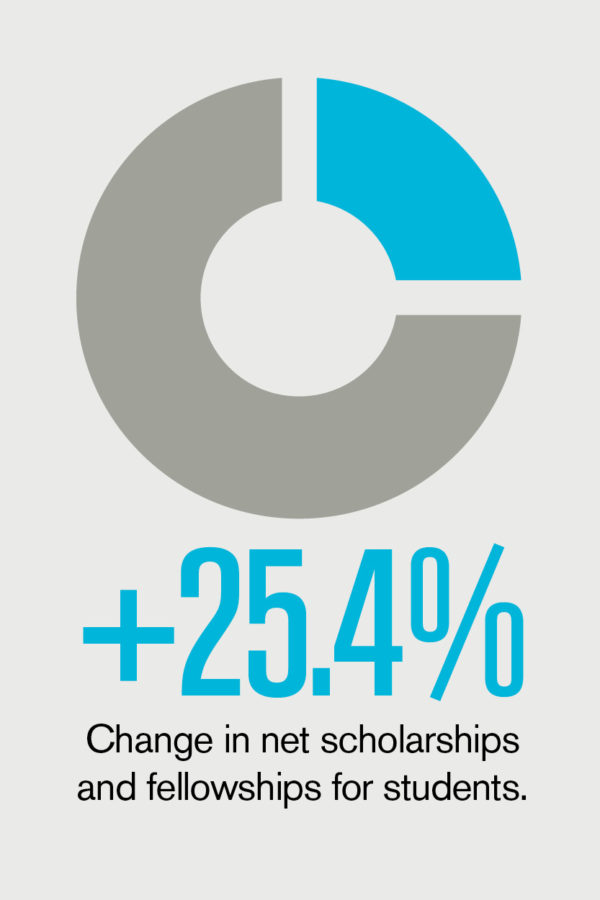

By The Numbers

Community College Revenue and Spending, FY03 to FY13

Source: Delta Cost Project at American Institutes for Research, Trends in College Spending: 2003–2013 Where Does the Money Come From? Where Does It Go? What Does It Buy?