Almost three years ago, I gathered the vice presidents of business services, one from each of the seven separately accredited colleges within the Dallas County Community College District (DCCCD), to discuss ways to cope with dramatic budget cuts.

I suggested we develop a change strategy based on an idea discussed by Dennis Jones, president of NCHEMS (National Center for Higher Education Management Systems) during one of his visits to Western Nebraska Community College, where I served as vice president of administrative services during the mid-1990s.

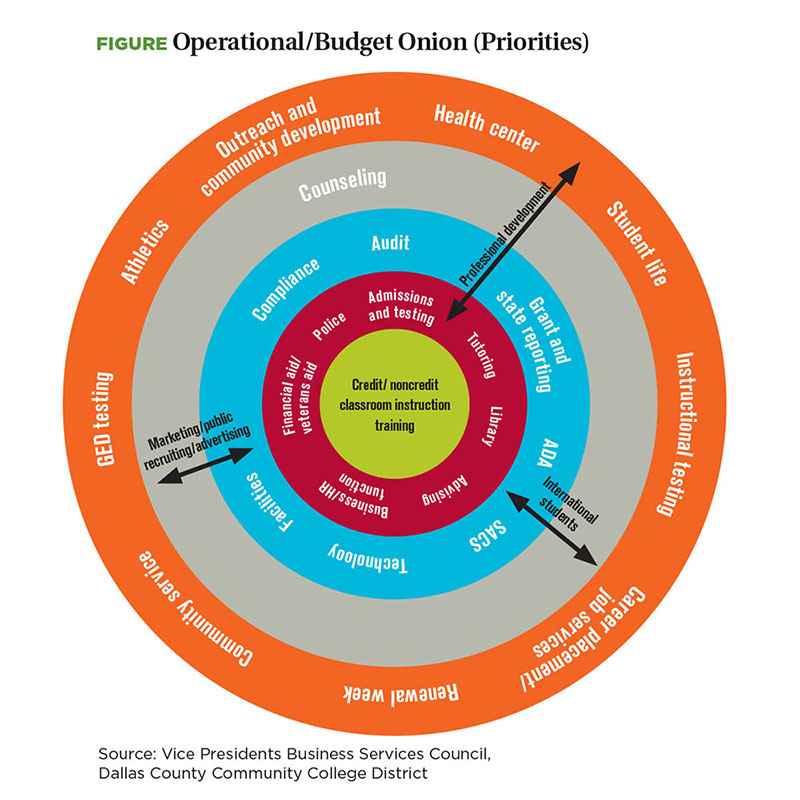

Jones likened an organization or higher education institution to an onion; peeling back surrounding layers can help identify the core activities that must be treated as priorities. In our case, we needed to adjust for budget cuts without touching our core- and mission-based activities.

The group of DCCCD vice presidents agreed that this might be a useful approach to arriving at budget goals. Initially, we cut $12 million from our FY11 budget. The following year, we cut an additional $18 million, for a total budget reduction across two years totaling $30 million, or roughly the 9 percent reduction in our general fund budget required by state shortfalls.

Removing the Wrappings

We met in August 2010 to identify the elements of our operational onion and its layers. Our efforts produced a graphic representation that incorporated the elements of our operational budget and the layers in which they seemed to logically fit.

As an alternative to across-the-board cuts in times of declining resources, we felt that college leaders should focus on, or establish, operational priorities, as we did via the information in the figure. For us, the core of the college operation is instruction. That’s why the community college exists.

If we then look at the basic elements of instruction, we first consider the students and the instructor. The classroom can be owned, borrowed, or rented; it can be bricks and mortar or virtual. The core of the college business exists in connecting students and instructors in pursuit of learning that leads to student success.

The first layer that wraps around the core represents those services required to connect students and instructors, create a safe environment, and attend to the basic business functions for maintaining the organization as a going concern. That includes the business and HR function, admissions and testing, advising, financial aid and veterans aid, the library, tutoring, and police or security.

Moving toward the outside of the onion, the next layer consists of functions that support what’s happening in the core and the first layer. This operational layer ensures long-term success of the college mission via activities and entities such as:

- Compliance with regional accreditation criteria.

- Compliance with state, federal, and grant agency requirements.

- Audit.

- Facilities.

- Technology.

The outer layers of another organization’s onion obviously will look different, based on institutional priorities, but the closer one gets to the core, the more similar these layers may look. As funding sources peel away layers of revenue and cut into budgets, colleges could also extract deeper cuts in their outer layers—to protect the core.

Keep in mind that the core itself is not always immune to reductions in resources. Instructional operations lend themselves to budgetary and priority stratification. Even though that may be happening in the classroom, the core can become an onion unto itself and be examined for layers of efficiencies and effectiveness.

Applying the Core Concept

While the core was easy to identify, we found that we had little “fluff” in our budget and few, if any, departments that weren’t somehow supporting student success. We found that some departments offered services that cut across various strata of the onion. For example, the international students office handles the I-9 visas required to get international students into the classroom—an extremely central activity. The same office also offers “softer” services, such as cultural awareness activities, an offering not so close to the core.

Another example is the organizational development department, which offers an array of staff-development programs, from facilitating mission-essential faculty development, to equipping faculty with tools, to better assist an increasingly challenging student body to dealing with topics that may be classified as “personal development.” Such departments’ budgets require extra time and analysis to disaggregate costs for services that traverse several departments.

The extent to which we used the onion concept to exact cuts in our district operations budget and the separate college budgets did vary. Here are a few of the decisions we made:

- Eliminated altogether the previously established districtwide budget provisions for salary increases.

- Put technology and facilities upgrades on hold.

- Reduced resources directed to student life activities and programs. We are a commuter college, and our students are not as dependent on such programs as are their peers at residential colleges and universities.

- Within the “district operations” administrative support unit, we reduced staff in the facilities management and planning department (with facilities upgrade projects on hold, we had reduced need for designers and project managers) and in the purchasing services department (since fewer budget dollars meant fewer requisitions and purchase orders).

One of our colleges used the onion approach to avert a knee-jerk reaction to its budgetary difficulties. David Browning, vice president of business services at El Centro College, reported that college leadership was considering an across-the-board cut in budget earmarked for adjunct pay, a measure that would have reduced enrollment. Instead, using the onion’s stratification as a guide, budget reductions were made in back-office staffing; student health center services (those that were available elsewhere in the community); and deferred technology, equipment, and facilities upgrades.

The onion is a tool, a means with which to weigh budgetary decisions. Like any such concept, the manner in which it is used depends on each college’s leadership team and its desire to employ such a process to stratify and prioritize budget layers.

Add Another Dimension

Fast-forwarding to 2013, we find that regardless of the prevailing currents of budgetary difficulties, the spotlight on higher education has moved to accountability issues, including, among other things, attendance costs; student success (in terms of completion, persistence to the next semester, graduation, and so on); student debt; and loan defaults.

In his State of the Union address in February, President Obama made mention of a “College Scorecard” that would provide transparency with regard to these same issues as well as details on graduate employment data. This scorecard will change the conversation about higher education, our resources, and the use of those resources.

Last fall, Sandy Shugart, president of Aspen Award–winning Valencia College, Orlando, addressed attendees at the Community College Business Officers’ 30th annual conference. In his presentation, Shugart asserted that business officers need to be delving deeply into analytics—spending less time watching and talking about enrollment levels and more time realigning budgets and operations to increase graduation rates and other critical student outcomes.

Paying attention to the right measures, he suggested, will enable us to (1) better control, if not reduce, student cost of attendance; (2) reduce transaction costs; and (3) place budgetary resources into the areas that most contribute to student success.

How does this relate to the onion? Do we still need it as we develop our budgets? I say, “Yes.” But we need to accompany it with an overlapping layer that helps us identify areas of opportunity. Business officers need to be part of that process, as we continue to streamline the right operations and priorities, while allowing our core mission to thrive.

EDWARD M. DESPLAS, executive vice chancellor, business affairs, Dallas County Community College District, Texas