The adage that you can’t determine what to do in the future unless you understand the past is true, in my observations. But, as higher education finance and facilities officers struggle with campus facilities strategies, analyzing past performance is not so straightforward.

Uncertainty surrounding energy-consuming operations is particularly problematic. What was true 10 years ago regarding energy costs was no longer accurate just 5 years ago. What was true 5 years ago is not necessarily true now—and what we project for the next 5 years or more may certainly be assumptions that become similarly suspect.

When calculating energy expenses, most managers understand that first costs may not be the biggest expense. Yet, lacking ways to predict energy prices over the next 30 years, managers plug in available assumptions and hope that the pricing structure turns out to be relevant.

A study conducted by researchers Carolyn Fischer, Evan Herrnstadt, and Richard Morgenstern, noted: “Based on analysis of the Energy Information Administration (EIA) 22-year projection record, we find a fairly modest but consistent tendency to underestimate the total energy demand by an average of 2 percent per year.”

Perhaps more important than cost projections are risk assessments related to different forms of energy. Thirty years ago, asbestos gained popularity as a facilities material because of its relatively low cost. After millions of dollars spent on litigation and cleanup efforts—and the toll taken on human health—it’s clear that the low-cost criterion was only one area of risk.

The same is certainly true for fossil fuels.

A Parallel Precursor

It’s useful to consider the asbes-tos issue from the 1950s as a unique analogy to today’s risks associated with fossil fuels. After World War II, campus managers faced a serious facilities problem: rapid campus expansion to meet the needs of the GI Bill. As building materials were assessed, asbestos became a product of choice, because it was abundant, naturally occurring, low-cost, and exhibited inherent fire-safety properties. In the following decades, asbestos was incorporated in as many as 3,000 building products.

For 30 years, asbestos was extensively used in pipe and building insulation, ceiling tiles, floor tiles, and even caulking materials. Then, in the 1960s and early 1970s, scientific research connected the dots between workers’ health and the presence of asbestos fibers. The most chronic cases of asbestos poisoning and related cancers were discovered in factory settings, but additional research also related asbestos exposures in buildings with asbestos products. In the early 1970s, asbestos became a substance subject to regulation by the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA).

Since that time, universities have spent millions of dollars on asbestos mitigation to negate a risk that was not included on anyone’s decision-making list when the material first gained popularity. Until science made the cause-and-effect connection, and the courts supported the findings, the risk was unknown.

It’s easy to see the risk similarities of asbestos and fossil fuel–based energy sources. For asbestos, however, we did not understand the exposure and risks for our institutions for several decades. On the other hand, with fossil fuels, science overwhelmingly agrees that carbon emissions are harmful to human health; the Supreme Court agrees—and as with asbestos—carbon dioxide is covered in the EPA clean air guidelines.

Policy and Politics

Few decision makers on campuses today can assess the extent of future potential risk related to carbon emissions. In fact, institutions could be at risk for adverse results spanning the life cycle of any energy-consuming facilities.

Our additional dilemma results from the lack of a national policy or consistent state policies that consider the cost-benefit relationships of energy options. Unfortunately, the results of both climate change and of our national and state politics are highly unpredictable and uncertain.

We do know that new energy-consuming buildings have a service life of 30 to 50 years. That is potentially 6 to 10 new administrations, congresses, governors, state legislatures, and governing boards.

So how do finance decision makers meet the challenges of keeping campuses safe, reliable, and cost-effective? We can take several actions:

- Commit to the same level of transparency in energy operations as we adopt in all other reporting processes. Any building that uses or emits potentially regulated carbon compounds should have a carbon transparency disclosure. This could take the form of a factual statement about expected performance of carbon-consuming and -emitting processes (rather than pros and cons of the energy source).

- As with asbestos, focus on what we know, and acknowledge there is more institutional risk in what we don’t know. Each institution needs to establish its own risk tolerance consistent with policies adopted by the governing boards.

- Require board approval of energy-consuming operations, with risk litigation as part of the planning process. Once the carbon transparency disclosure is understood, regulated compound off-ramps, fuel flexibility, and other elements might be part of the design process. As risks become quantifiable, energy operations may transition to less risky energy sources.

As institution leaders, we have an obligation to inform our leadership and governing boards. A carbon transparency disclosure should be part of that information process. Discussions among institutional leaders to arrive at such disclosures can lead to a more inclusive approach to the way risk assessment and energy management intersect with carbon emissions.

SUBMITTED BY Lowell Rasmussen, vice chancellor, facilities and finance, University of Minnesota at Morris

Owned by Rollins College, Winter Park, Fla., the Alfond Inn redefines higher education philanthropy. Established as a venue for the Alfond Collection of Contemporary Art for Rollins College, the hotel also serves as an extension of Rollins’ Cornell Fine Arts Museum. Both entities display some of their collections in the hotel’s public areas.

The 112-room boutique hotel opened in August 2013 and features rotating displays from the contemporary art collection. The property also features a restaurant, fitness center, and 10,000 square feet of meeting space. Earning a AAA Four Diamond status just eight months after opening, the hotel has become a hub for top-level association meetings.

- Strong educational funding component. The Alfond Inn was funded in part with a $12.5 million grant from the Harold Alfond Foundation. The additional $20 million was financed by Rollins’ cash reserves. The intent for the foundation’s contribution was that the net operating income of the inn would be directed to the Alfond Scholars program over the next 25 years—or until the endowment principal reached $50 million, whichever came later.

In fact, the inn has greatly exceeded expectations, with projected net income of $1.9 million in 2014 being far surpassed, with an expected end-of-year total reaching approximately $4.3 million. Following a loan payment, the inn expects to give back $3.2 million to the scholars program.

“This year [2014], $157,000 will be used for three full scholarships,” explains Jeffrey G. Eisenbarth, vice president for business and finance and treasurer at Rollins College. “It’s so much better than what we had projected.”

- Unique art showcase. Rollins’ Alfond Collection of Contemporary Art is a growing collection of more than 220 works of art conceived as a “visual syllabus” for the college—including paintings, photographs, sculptures, and mixed-media works by established and emerging artists around the world. “These artworks are a new and important chapter of our collection,” says Ena Heller, the director of the Cornell Fine Arts Museum.

To highlight the art component, the hotel offers complimentary guided tours of the art collection every Friday, and changes the installation every few months, as new acquisitions arrive. “I can’t think of another museum that uses a hotel property as an extension of its exhibition space,” says Heller.

Late last year, the Lumina Foundation awarded a grant to the National Student Clearinghouse to support the clearinghouse’s landmark project to provide the first, national, automated solution for exchanging reverse transfer student data. Leaders estimate that the initiative could result in as many as two million students becoming eligible for associate degrees.

Reversal Rules

The reverse transfer process involves four-year institutions identifying the number of credits a student previously earned at a two-year institution and transferring those credits back to the particular institution—thus providing the opportunity for the student to qualify for an associate degree. The program allows the latitude for the student to have (1) transferred to another associate degree-granting institution first, (2) transferred to a bachelors’ level institution, (3) attended a public or private institution, or (4) transferred across state lines. If eligible, under any of these circumstances, the student can be awarded an associate degree.

According to a Lumina-funded study, 78 percent of students transfer from a community college to a four-year college or university without a degree. Eligible students will now be able to change that, with the opportunity to be awarded a first associate degree that reflects educational achievement and allows them to compete more effectively in advanced higher education pursuits and in the workplace.

“The clearinghouse’s reverse transfer project is a major step in improving higher education outcomes, which will benefit us as a nation,” says Walter G. Bumphus, president and CEO of the American Association of Community Colleges. “More students will get the degrees they deserve. Community colleges will be recognized for the value they add to education. And—by granting more degrees—states will be better positioned to attract new business.”

“Our research shows that those transferring to a four-year institution, after having received an associate degree, are more likely to complete [college],” notes David Pelham, vice president of higher education development and client relations at the National Student Clearinghouse. This fact, along with other related benefits of degree completion, hasn’t gone unnoticed. Many states, including Texas, Missouri, Ohio, and Tennessee, are expected to adopt the reverse transfer.

Tailoring a Two-phased Process

The clearinghouse is creating a standardized, streamlined process to assist institutions in transferring credits more efficiently and securely. And, the project funds the work, so there are no fees.

Two major efforts will facilitate the detailed program:

- Data gathering. During the initial phase of the reverse transfer process, four-year institutions will send academic data files to the clearinghouse for students who have agreed to participate and have reached a specified number of credit hours. Upon receipt of the files, the clearinghouse alerts the appropriate two-year institution that the student’s record is available for downloading. At that point, two-year institutions can download all records from all four-year institutions in which their students have transferred, for consideration of a reverse transfer degree. Institutions in Missouri, Texas, and Wisconsin are already working on phase-one development.

- Transparency tools. Phase two will allow individual students to access from the clearinghouse all data that apply to their degree eligibility, and the means to resolve perceived discrepancies. In addition, the process includes a plan to roll out a nationwide data mart to enable enrollment records to be cross-checked against the student’s academic records, ensuring better accuracy.

Spreading the Word

Sponsored jointly by the National Student Clearinghouse and the Institute of Higher Education at the University of Florida, Orlando, the Reverse Transfer Policy Summit is slated for January 24 and 25. National, state, and institution-level higher education officials from all 50 states will gather to learn more about facilitating the reverse transfer of credits.

For more information, go to www.studentclearinghouse.org.

Business Officer’s Business Intel department offers increased publishing opportunities for ideas and initiatives your college or university is exploring. Send us a brief description of a project, product, process, or repositioning plan that is working or gaining traction on your campus. Don’t hesitate to include insightful professional development tips your colleagues and peers may find useful.

Here are a few topics you might consider writing about:

- Effective collaborations or shared services.

- Succession plans for the institution as well as for your division or department.

- Human resources initiatives that support faculty, staff, and students.

- A conference or professional development idea that you were able to bring back and implement on campus.

- A book that you’ve found particularly helpful.

Send your ideas to editor@nacubo.org, and you may see them in print!

“Who do you go to for candid feedback and advice? Who are you accountable to? It’s time to form your own board of advisers and let them hold you accountable. Identify three or four people who you respect in different facets of your life and invite them onto your board. Set expectations and let them know you need them on your journey through the year.”

—Shawn Parr, “Ten Steps to a Better More Productive You in 2015,” Fast Company, December 2014

Fast Fact

Professional Development Platform Goes Live

In December, the National Association of College Auxiliary Services, the largest support organization for higher education auxiliary and ancillary services, launched NACAS TV. The video platform features webcasts of NACAS events, features on industry best practices, and other professional development programming. “We are pleased to offer this new service to our members,” said the association’s CEO Ron Campbell. “NACAS TV is an important step forward in maximizing the use of technology to provide best-in-class professional development programs.”

Foundation Adds Online Accounting Facts

In mid-November, the Financial Accounting Foundation (FAF) announced its new educational portal to highlight the benefits of preparing financial reports according to GAAP. While many institutions regard GAAP as the “gold standard” of financial reporting for public companies and state governments, many other organizations are not as familiar with the approach. A section on the FAF site is dedicated to ways in which the FASB and the GASB are working to simplify and improve GAAP.

![]()

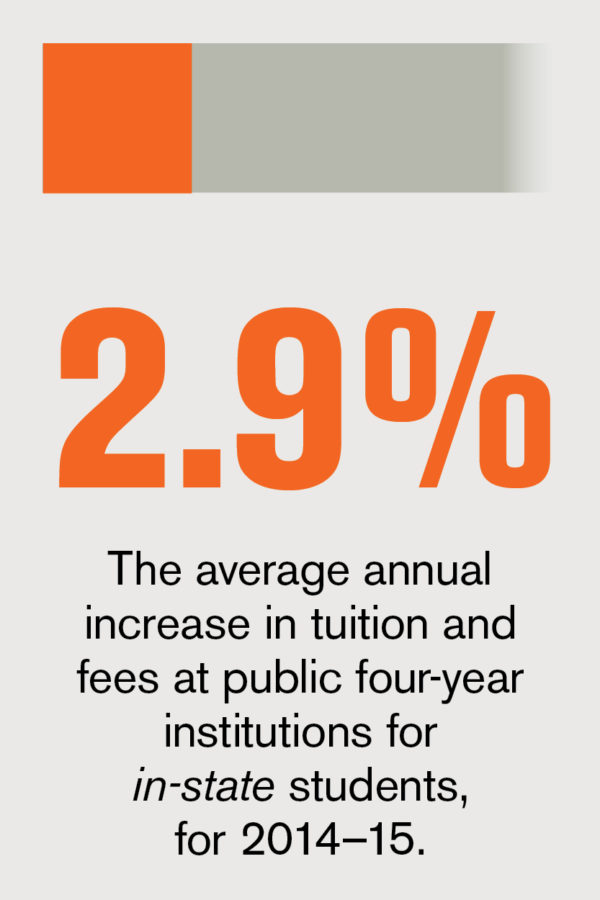

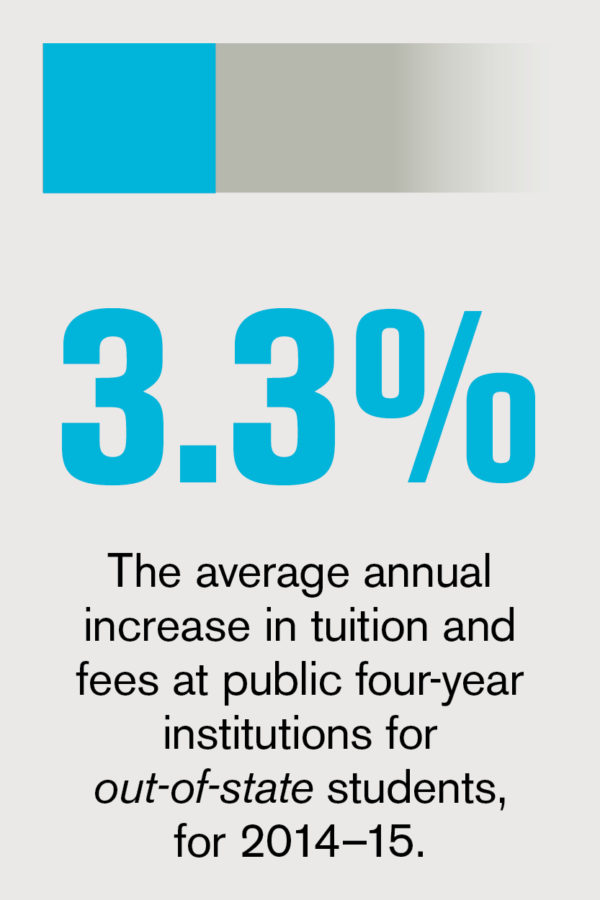

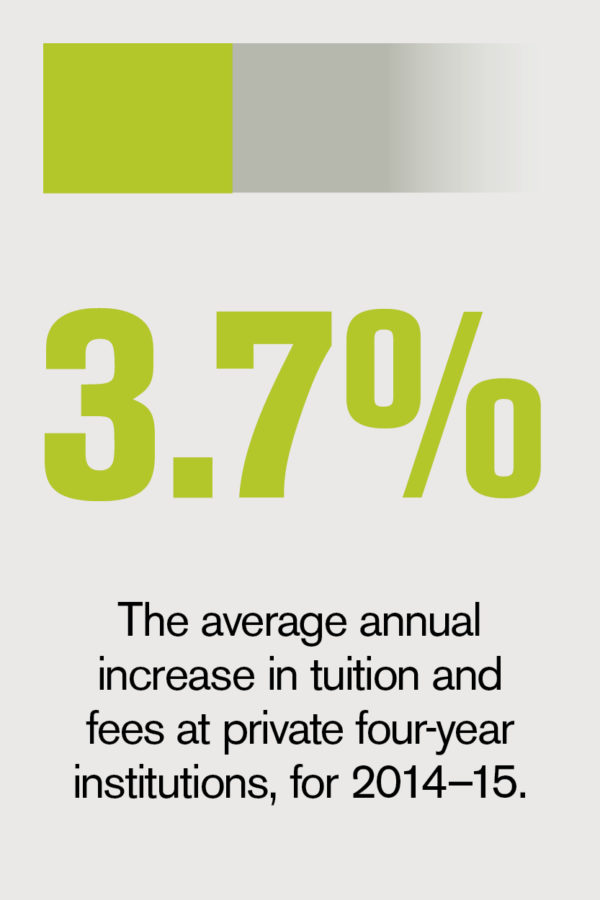

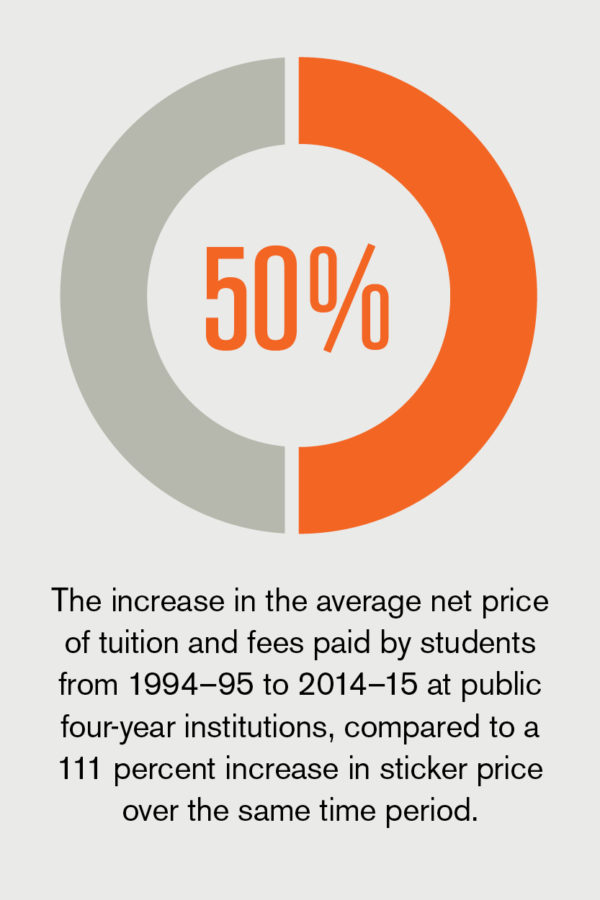

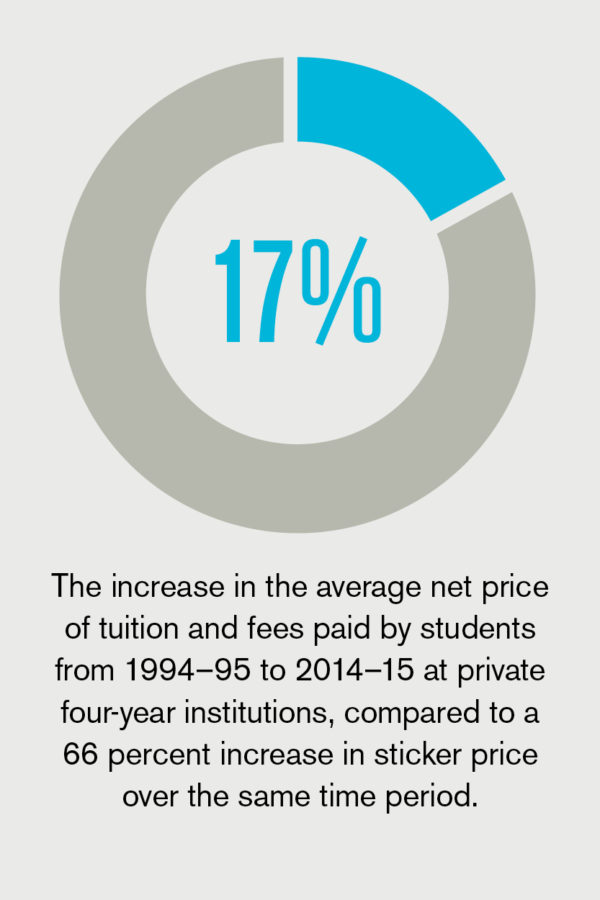

By The Numbers

Trends in College Pricing and Student Aid

Source: Trends in College Pricing 2014 and Trends in Student Aid 2014, College Board, November 2014, https://lp.collegeboard.org/trends