One of UMass Amherst’s permaculture gardens is located just outside Franklin Dining Commons. Credit: Keith Toffling

One of the first signatories of the Real Food Challenge Campus Commitment, the University of Massachusetts (UMass) Amherst has pledged to serve at least 20 percent “real food” (local, sustainably grown, and humanely raised) by 2020. Chancellor Kumble Subbaswamy signed the commitment in 2013, with the additional goals of finding creative ways to build partnerships, support regional growers, and serve more sustainably sourced food in the dining commons. (For further details on campus dining trends, read “A Method to the Menu.”)

These plans fit right into our Permaculture Initiative, originally proposed in 2009 by a group of passionate Amherst students, who presented their idea to Ken Toong, executive director of Auxiliary Enterprises. The term “permaculture” (coined by Australians Bill Mollison and David Holmgen) combines the concepts of permanent and agriculture).

At UMass, we’ve applied this new approach to our campus, planning edible and ecological landscapes, because they are replicable, scalable, and can be adapted to almost any climate. For our campus, the plantings would provide nutritious food to the dining commons in an environmentally conscious manner and create learning opportunities for students and volunteers.

Since its inception, the initiative has expanded to form partnerships with three different entities within the UMass system: the Permaculture Committee, the Stockbridge School of Agriculture, and UMass Dining—all working together to provide not only healthy food but to create a more sustainable community and improve health and lifestyle.

Local Food, Redefined

A number of permaculture gardens give new meaning to the term “local,” as they grow within feet of the campus dining commons. The plantings were so well received that the university has committed to adding at least one new garden on campus each year, with another being installed in spring 2014 outside the newly renovated Hampshire Dining Commons.

The permaculture landscapes visually demonstrate community resiliency, promote bioregional food security, and strengthen community partnerships. In March 2012, the university’s Permaculture Initiative was recognized by President Obama as a winner of the Campus Champions of Change Challenge, hosted by the White House.

Specific benefits to the community include:

- Offering hands-on education about regeneration—and specifically how to convert unproductive grass lawns into edible, low-maintenance, aesthetically pleasing gardens.

- Engaging local K–12 schools and nonprofits, such as Big Brothers and Big Sisters organizations, in the garden- planting process.

- Supporting local businesses through purchasing of plant material as well as other items for educational workshops and meetings.

- Creating beautiful spaces where students can gather, faculty can teach, and visitors can learn through garden tours and descriptions.

- Providing fresh, local, and organic food for all to enjoy.

Ecology Economics

Growing food directly on campus offsets the cost of purchasing conventional foods of similar quality. The savings and revenue earned through grants and awards as a result of the Permaculture Initiative also represent financial opportunities associated with this kind of sustainability program.

Purchasing locally can also work to our economic advantage. We recently shifted from conventionally raised eggs to local, cage-free eggs—and saved money in the process. We also factor in the idea that environmental and social responsibility have unmeasured value. Overall, the university has increased local produce purchases from 8 percent to nearly 30 percent in less than a decade.

The learning curve has taught us creative problem solving as well. We are discovering ways to source additional portions of our food locally. For example, one large farm two miles from UMass serves as a broker for 25 other local farms throughout the year, streamlining the supply chain and making it possible to source more products from the local economy.

Because the student body is so attuned to the sustainability movement, UMass Dining sources locally, even when purchasing from small producers proves slightly more costly than sourcing from large-scale distributors. Interestingly, fulfilling these kinds of student demands has coincided with an increase in our meal plan enrollments.

In addition, the cost of transporting dining waste to a local farm for composting is actually cheaper than landfill or incinerator alternatives, making this reciprocal partnership between rural community and the university both financially and environmentally sound.

Continuing the Commitment

One of the first steps toward reaching our new goal of achieving the Real Food Challenge Campus Commitment is to use the “real food calculator,” a tool created for campuses to evaluate their current purchases and research ways to shift purchasing to more “real food.” Each semester, UMass Dining and Stockbridge School of Agriculture will sponsor students who will receive academic credit to run the calculator, research food distributors, analyze data, and provide recommendations for strategies to source more real food.

As one of the largest foodservice providers in the nation, UMass Dining recognizes its vital role in setting examples of healthy, delicious, and sustainable eating.

With the signing of the Real Food Challenge Campus Commitment, the university will be redirecting nearly $5 million of our food budget to sustainable purchasing over the next few years.

SUBMITTED BY William O’Mara, Marketing and Communications, UMass Auxiliary Enterprises, University of Massachusetts, Amherst

In its business program, Paul Smith’s College, located in the Adirondacks Lakes region of New York, boasts a mere 30 business majors, along with the 110 students who are minoring in the subject. Yet, the small, private college reports 90 percent job placement for its business school graduates. Why the high success rate? “It’s all about the real-world experience,” says Diane Litynski, the college’s director of business. One of the projects the college’s business students are working on now is a plan to help grow the restaurant business on campus.

The college’s programs in hospitality, resort management, and culinary arts include a series of hands-on learning experiences, which are an integral part of most coursework. Campus facilities offer experiences in six commercial-quality food laboratories, a baking lab that supplies its A.P. Smith’s Bakery, and two upscale on-campus restaurants open to the public. The St. Regis Cafe offers lakeside dining, while The Palm features a menu inspired by the legendary Palm steakhouses—of which Wally Ganzi, a Paul Smith’s graduate, is co-owner.

The practical work is further reinforced in a semester-long series of hotel, culinary, and food service jobs, with students working off-campus with a variety of industry professionals. The experience often provides students with paid employment opportunities that support individual career goals.

South Dakota legislators have provided $300,000 in start-up funding for new projects that address the nation’s most pervasive counterfeiting and security problems. The South Dakota School of Mines and Technology, Rapid City, will serve as the lead institution for a newly created Center for Security Printing and Anti-Counterfeiting Technology (SPACT). The University of South Dakota, Vermillion, and South Dakota State University, Brookings, are collaborating on the project.

Earlier research at the School of Mines has already led to the creation of quick response (QR) codes that remain invisible in ambient lighting but are readable with a near-infrared laser and can be scanned using a smart phone. This is one type of technology that could be used to thwart counterfeiting, detect national security breaches, and be used in many other applications. Over the past three years, this particular research has resulted in several patent disclosures as well as negotiations for commercialization.

Other SPACT research and development includes creating nontoxic fluorescent inks for printing on pharmaceutical packaging, developing techniques to determine the source and authenticity of pharmaceuticals, and security printing of covert markings and labels.

Another grant to the School of Mines consists of $200,000 to encourage research innovation, upgrade existing laboratories, and develop new state-of-the-art labs for large-scale production and manufacturing.

“Our researchers are at the forefront of advanced manufacturing and anti-counterfeiting technology,” says Heather Wilson, president of the South Dakota School of Mines and Technology. “We hope to use these awards to continue to grow the research done at [the School of] Mines, and transfer technology to industry to create better products and more high-paying jobs.”

Emerging data from a study done by the University of Pennsylvania Graduate School of Education show that massive open online courses (MOOCs) have relatively few active users, that user engagement falls off dramatically over time—especially after the first one to two weeks of a course—and that few users persist to the end of the course.

Fast Fact

Impact of Student Grants on Sticker Price

The most recent report by the National Postsecondary Student Aid Study (NPSAS), “Price Estimates for Attending Postsecondary Education Institutions,” is based on a nationally representative survey of 95,000 undergraduates and 95,000 graduate/professional students. Study participants attended 1,500 different U.S. postsecondary institutions, anytime between July 1, 2011, and June 30, 2012. In part, the study looks at “list price” of the institution; the “net price,” which is the total price of attendance minus any grant aid received; and the “out-of-pocket” price, which is the difference between the list or sticker price and the total financial aid from all sources (grants, loans, and work-study).

Obviously, the charges paid by undergraduates vary greatly by institution type. While sticker prices ranged from $34,400 at four-year private colleges to $8,700 at two-year public colleges, the effect of student grants and other funding reduced the average out-of-pocket expenses to $9,600 per year for four-year public schools, $15,000 per year for those enrolled at four-year private institutions, and $6,000 at community colleges.

Higher Ed Reaps Rewards in the Long Run

“How Education Pays Off for Older Americans,” released in January 2014 by the Institute for Women’s Policy Research, indicates that higher education results in higher pay for women—and men—50 and older. Those with at least some education beyond high school work more at older ages and earn more per hour, relative to those with less education.

The report examines differences in work and wages among women and men age 50 and older at different levels of educational attainment, and includes information about the most common occupations for men and women by age.

Findings of the study include the following:

- Women in the two highest education groups earn about the same salaries as men who have attained one educational group lower. In other words, women with bachelor’s degrees earn about what men with some college or an associate’s degree earn.

- Women with advanced degrees lose more earnings with age than men do.

- Estimated earnings for older Americans, from age 65 until retirement, are three to nearly five times higher for those with advanced degrees compared to those with only a high school education or less.

![]()

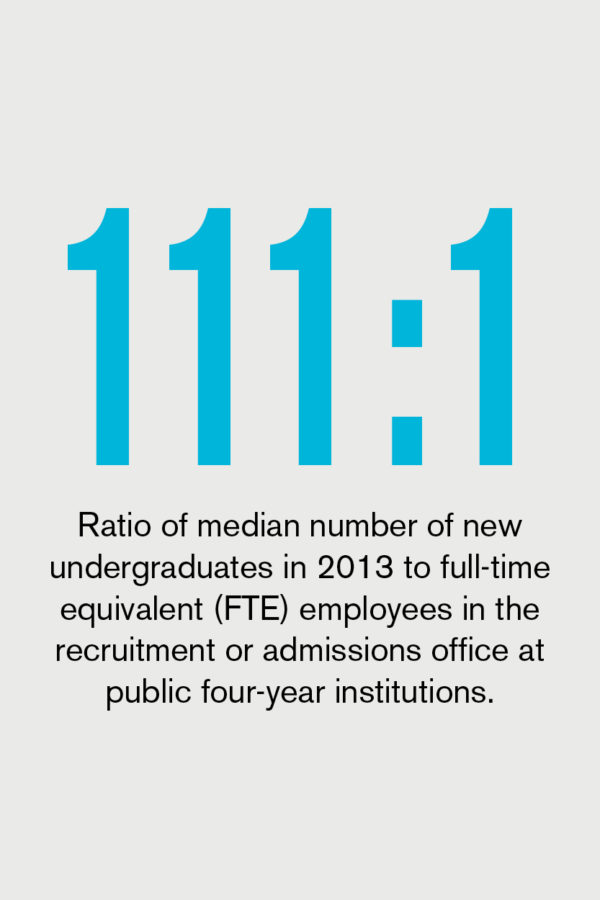

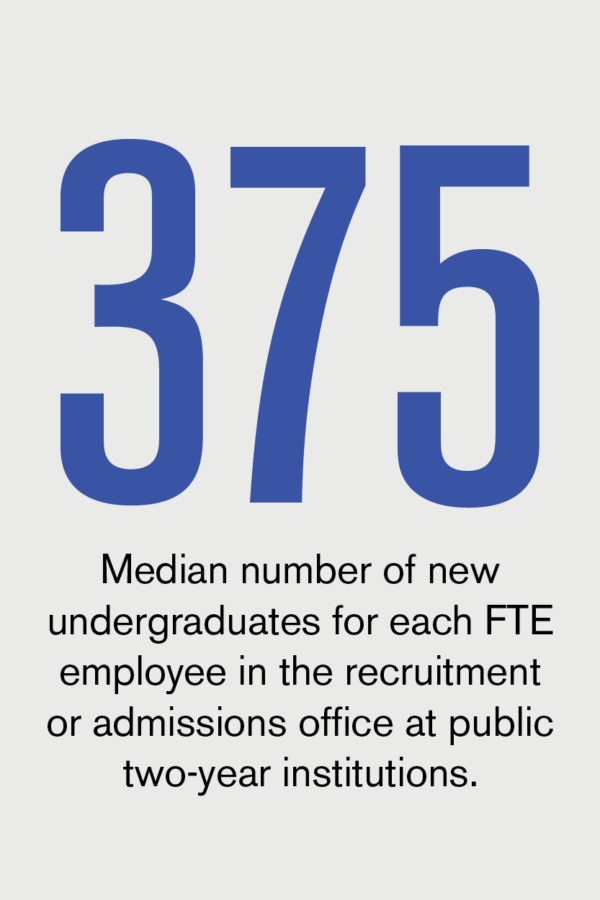

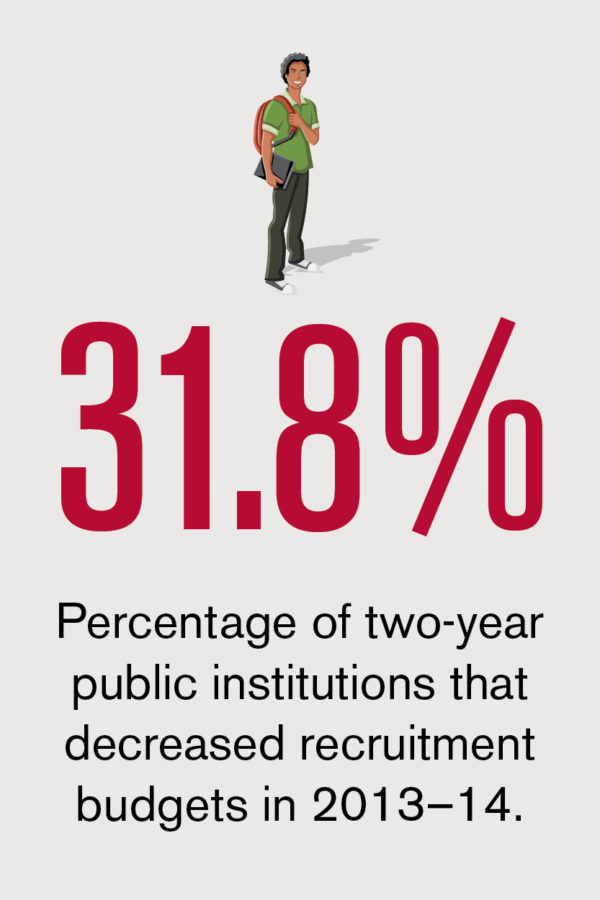

By The Numbers

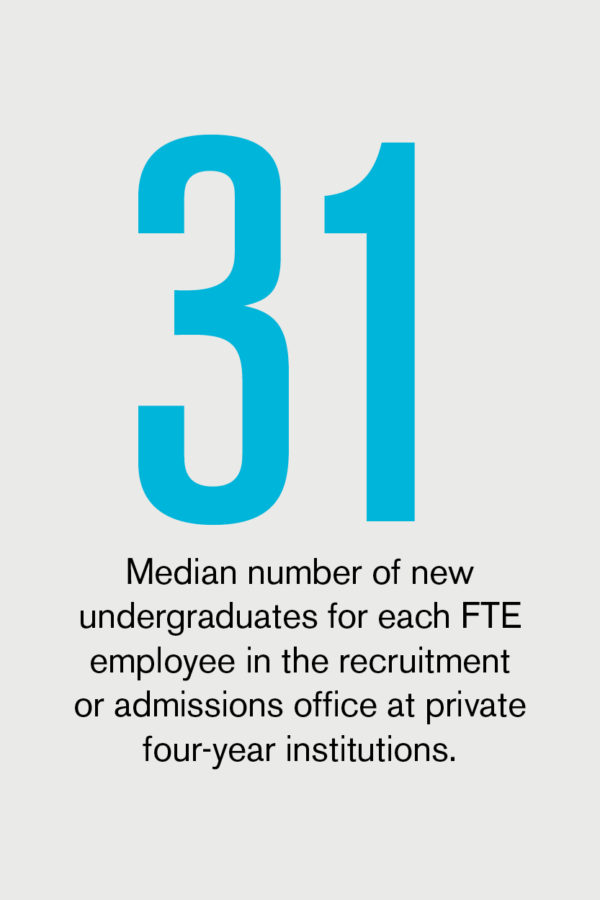

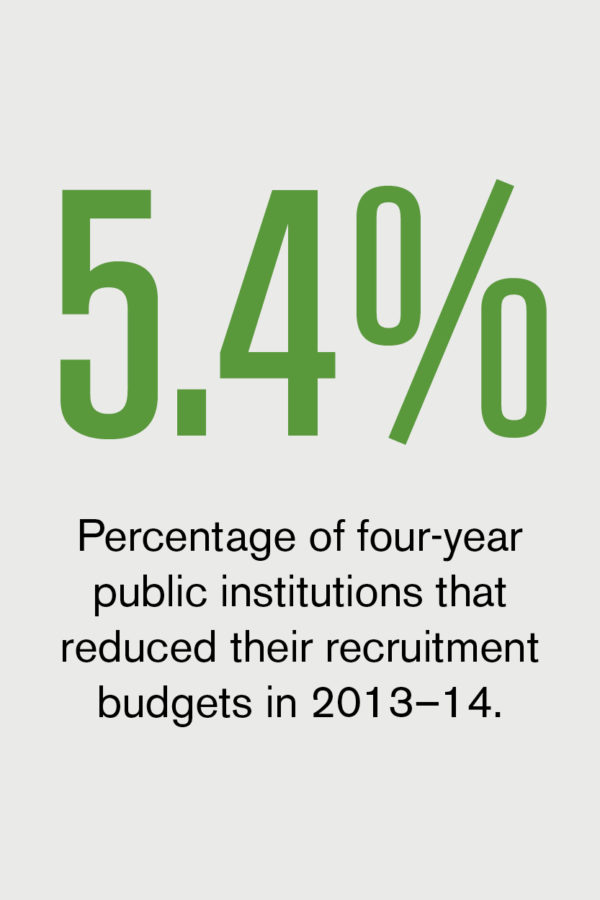

2013 Cost to Recruit Undergrads

Source: “2013 Cost of Recruiting an Undergraduate Student, Benchmarks for Four-Year and Two-Year Institutions,” Dec. 13, 2013, Noel-Levitz; www.noellevitz.com/documents/gated/ Papers_and_Research/2013/2013CostofRecruitingReport.pdf?code=42810179201453