Reality is rapidly catching up with prior predictions of topsy-turvy population change. The most recent U.S. Census indicates that by 2019, minority children will become the majority; and by 2043, whites will no longer make up a majority of Americans.

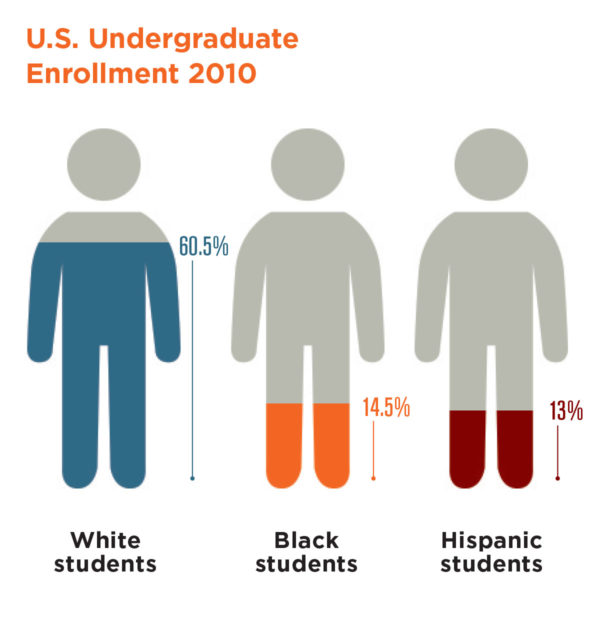

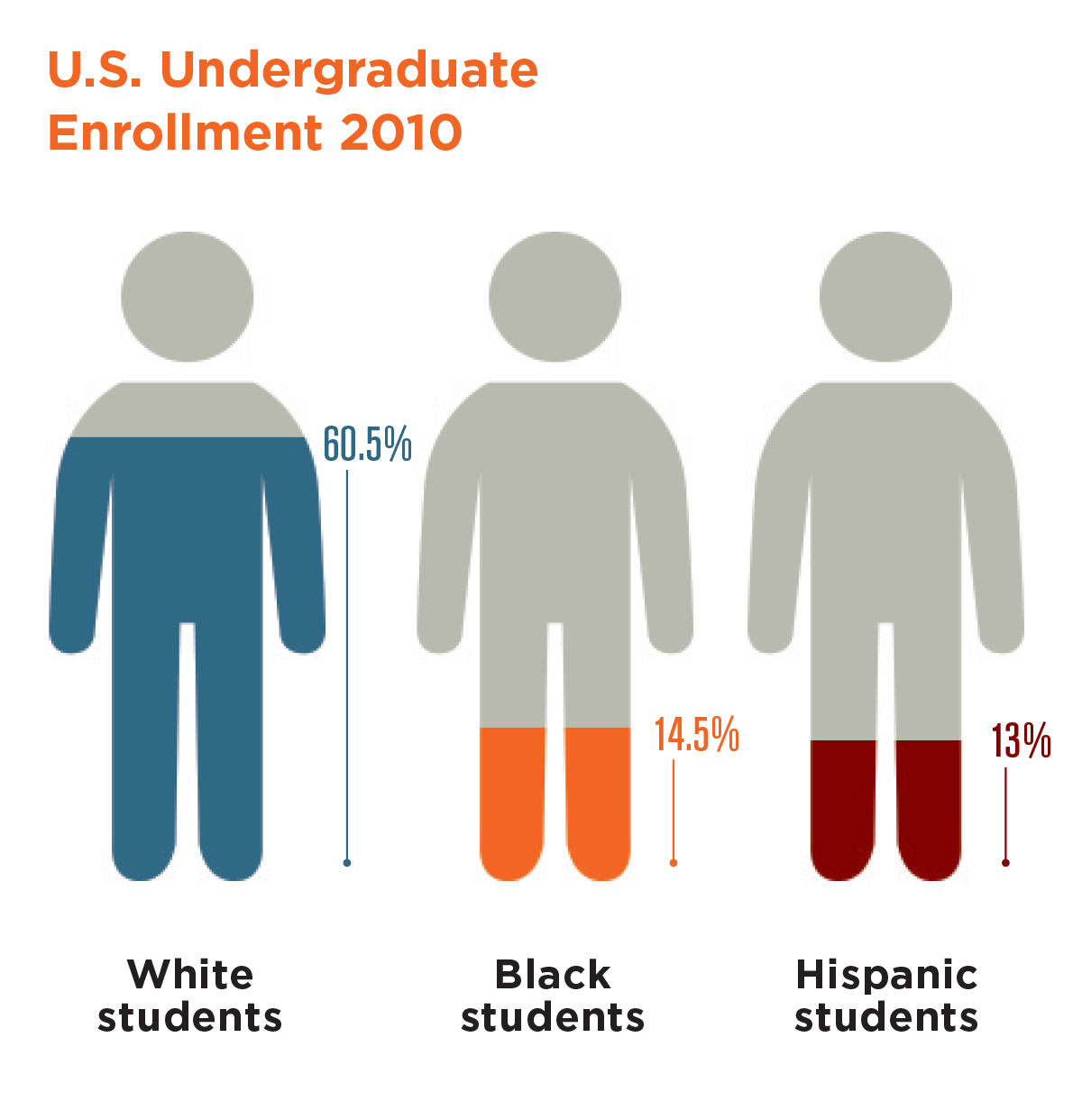

According to the National Center for Education Statistics (NCES), undergraduate enrollment of U.S. residents in degree-granting postsecondary institutions has decreased for white students from 68.3 percent in 2000 to 60.5 percent in 2010. However, enrollment of black (from 11.3 to 14.5 percent) and Hispanic (from 9.5 to 13 percent) students increased during the same time period. Clearly, much like the country as a whole, college campuses are becoming more diverse.

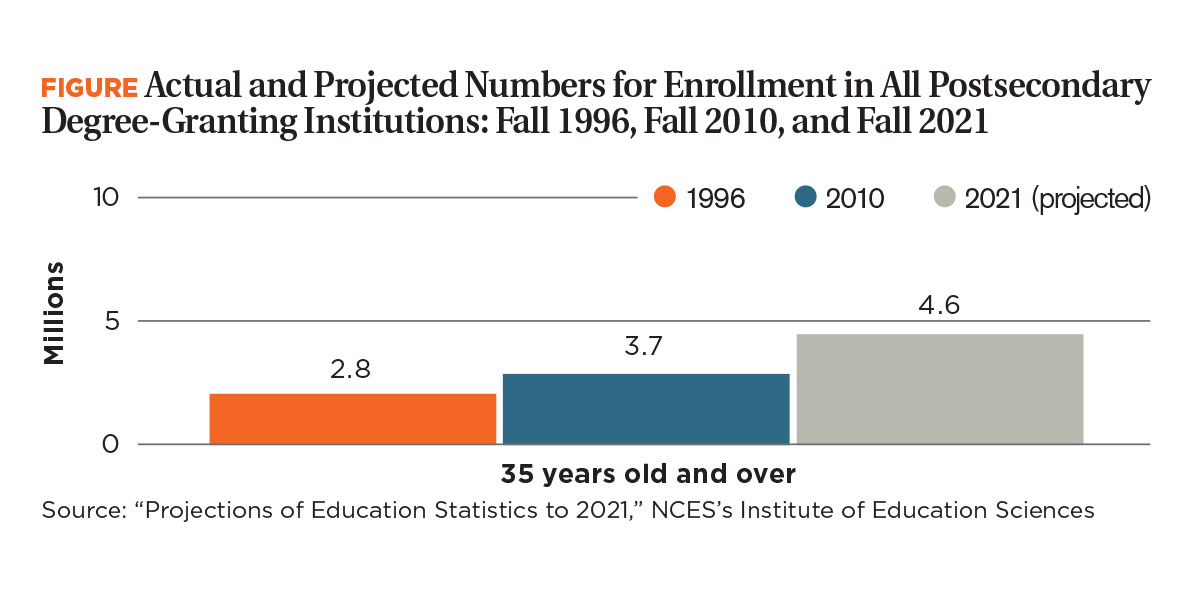

Race and ethnicity are not the only elements of the changing student mix. Prolonged unemployment has led to increasing numbers of adult learners returning to school to complete their degrees or be retrained in new fields. “Projections of Education Statistics to 2021,” published by the NCES’s Institute of Education Sciences, reports an increase of 32 percent in enrollment of students 35 or older between 1996 and 2010. That number is projected to increase by another 25 percent between 2010 and 2021.

Many adults returning to school are military veterans. In a recent report, the Council for Adult and Experiential Learning (CAEL) indicated that “since May 2009, the Department of Veterans Affairs has spent approximately $18 billion under the Post-9/11 GI Bill to provide education benefits to nearly 720,000 veterans.” However, while financial support is available for veterans’ education, according to the CAEL report, members of Congress and others have raised concerns that far too many veterans do not earn degrees.

Veterans are not the only group experiencing difficulty in degree completion. In general, the number of Americans actually completing degree programs has been decreasing. According to the National Information Center for Higher Education Policymaking and Analysis, just over half of students who start four-year bachelor’s degree programs full time finish in six years. Further, the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) reports that in 2012 the U.S. ranked 14th in the world for the percentage of young adults (25–34) with college degrees.

As these trends illustrate, degree completion has become more difficult for all students, including those from nontraditional groups. According to NCES data for 2010, 61.5 percent of white students who attend four-year colleges full time complete their bachelor’s degrees within six years, compared to 50.1 percent of Hispanic students and 39.5 percent of African-American students.

These overall changes in demographics and degree completion rates beg the question: Once nontraditional students come to your institution, how will you support them and ensure their success? Without a doubt, it’s challenging to be all things to all kinds of students. Still, some institutions have expanded their efforts to build integrated programs that—while they certainly benefit all students—place special emphasis on supporting specific groups of nontraditional students by focusing on enhancing both their academic and social experiences.

A warm welcome for veterans. The University of Nebraska Omaha (UNO) has a long tradition of supporting veterans and other students with military affiliations. Students led formation of the Pen and Sword Society, which was in existence from 1957 to 2004, and later the Veterans Student Organization, which became a recognized chapter of the Student Veterans of America in 2011.

In the Military Times’ “Best for Vets: Colleges 2013” survey, UNO ranked No. 6 among more than 60 four-year institutions. UNO received recognition for having a significant number of veterans on staff and providing comprehensive academic support services.

However, when the university surveyed its military students recently, “it was apparent that they wanted to go one place where the focus was on them,” says Jennifer Carroll, director, military and veteran university services office. “They wanted a one-stop office for admissions, Veterans Administration and Department of Defense education benefits, federal financial aid, degree programming, a veteran student lounge, and disability services.”

This was the impetus for opening Carroll’s office last April. Prior to that, the veteran services department was housed in the university’s financial aid office. As its mission statement indicates, this new office is “committed to providing high-quality, comprehensive student support services and student programming that ensure [veterans’] successful recruitment, transition, academic progress, and graduation at UNO.”

Countdown to completion. Cheyney University, a small historically black college/university (HBCU) in Philadelphia, is one of many institutions around the country that have invested in creating worthwhile adult learning experiences. Its newly renovated campus, Cheyney University City Center, is conveniently located downtown, so it is easily accessible to working adults starting or finishing degree programs.

Countdown to completion. Cheyney University, a small historically black college/university (HBCU) in Philadelphia, is one of many institutions around the country that have invested in creating worthwhile adult learning experiences. Its newly renovated campus, Cheyney University City Center, is conveniently located downtown, so it is easily accessible to working adults starting or finishing degree programs.

According to data provided by the university’s office of enrollment management, the majority of the students participating in degree programs at the City Center campus are working adults ranging in age from 26 to 42; the average age is 35. Most have children, 99 percent are African American, and the ratio of female students to male students is five to one.

“We want to offer the Cheyney experience to as many students as possible,” says Donna Parker, dean of faculty and academic schools. “With the 18- to 22-year-old demographic shrinking, expanding our outreach to adult students is key to the institution’s growth.”

Degrees of diversity. Georgia State University, Atlanta, has taken a comprehensive approach to supporting minority students, many of whom are first-generation college attendees. “The majority of our Latino and African-American students are first-generation,” says Linda Nelson, chief diversity officer and assistant vice president for human resources. “We’re so diverse, and we have been for a number of years.” For that reason, Nelson and others have focused on encouraging these students to be involved in campus activities across the board and to take advantage of the support services available to them.

“The reality is that we have to have systems in place not to lower the bar, but to support first-generation students who don’t have the advantage of knowing how the higher education system works,” says GSU President Mark Becker. “We have to show them how to thrive academically and meet their financial obligations, as well as offer them enriching experiences on campus.”

This question of how best to provide support in the right areas, grow student enrollment, and attempt to ensure degree completion constitutes one of the most critical issues facing higher education institutions, as they evaluate the manner in which demographic shifts across the country will likely influence their culture and sustainability. Here’s a closer look at the programs of these three institutions, which are taking a comprehensive and proactive approach to supporting nontraditional students.

At Your Attention

“Are you a veteran?” UNO’s Carroll, who served in the U.S. Coast Guard for a number of years of active duty and four years in the reserves, expects this to be the first question many military students will ask her when they visit the military and veteran university services office (MaV USO).

“Everyone in our office is a veteran or currently serving in the military,” she says. “The more experiences the employees bring to the table, the more comfortable the students will be. They’ve dealt with bureaucracy the whole time they were enlisted; now they want to be treated like people.”

Along these lines, she emphasizes that other than those using the GI Bill, students self-identify as to their military affiliations. Consequently, the office takes this approach: “We’re here. If you need us, come see us. No one is being targeted.”

Under Carroll’s direction, MaV USO currently supports 2,000 students who are veterans, active duty personnel, or otherwise affiliated with the military (i.e., spouse or child of a veteran). Nine hundred of these students are using the GI Bill, which means the university has to provide standard reports to the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs on the level of the individuals’ academic success.

“Veterans are a different breed of student,” Carroll says. “They’ve earned a benefit and want to be successful.” UNO is invested in that goal. Among other support services it provides, the military services office can put financial holds on individuals’ accounts to make sure students meet with academic advisers, or someone from MaV USO may phone a student to review his or her grades if it’s discovered that the semester performance wasn’t good.

In addition to these more administrative functions, says Carroll, one of the “most beneficial components of the office is the student lounge where students can congregate. When you leave the military, you leave that sense of camaraderie, which you rely on heavily while enlisted,” she continues. “Our office builds up students and gives them that sense that they are family here.”

Another primary objective is to make military and veteran students feel welcome by emphasizing the benefits of their real-world experiences. “Veterans bring global background and knowledge that can only improve the classroom,” Carroll says. “We see this as a positive influence on our typical students.”

This desire to have veterans on campus is evident in the university’s ongoing practice of giving academic credit for being in the service, attending military schools, or earning specific kinds of certificates. UNO began the practice in the 1960s when its Division of Continuing Studies developed a bootstrapping program designed to help active-duty students from nearby Offutt Air Force Base and other military organizations to obtain degrees.

One of the key takeaways the American Council on Education identified during its 2008 summit for college and university presidents, “Serving Those Who Serve: Higher Education and America’s Veterans,” was considering “the veteran experience as part of your [institution’s] admissions and transfer credit evaluation process.”

Even with institutional and campus commitment to this area, however, disconnects exist between veteran students and the faculty or staff—something MaV USO recently determined after surveying the students the office supports. While Carroll estimates that more than 100 UNO faculty and staff have military affiliations, she says it’s her office’s responsibility to conduct outreach and raise awareness of issues involving veterans transitioning to the campus.

As a result of the survey, MaV USO will launch military-awareness training for faculty and staff, conducting one-hour training sessions to convey unique details, such as differences in deployment policies for students on active duty versus those serving in the National Guard.

From Carroll’s perspective, efforts made possible through the launch of her office—along with an ongoing commitment to maintain UNO’s military students task forces—mean that you “get more support and more people wanting to participate, which sparks interest in developing similar offices universitywide so that we can expand the reach of our programs.”

She adds: “We’re involved in their success from start to finish. Once you’re at UNO, you’re not going to leave us before you get your degree.”

Adult Access and Achievement

“It never occurred to me that I could go to college.” Comments like this one made earlier this year at a Cheyney University forum on “Collaborative Solutions to Reduce Gun Violence” reaffirm Donna Parker’s belief that it’s important for the institution to capture the market for working adults. Events like the forum, presented as part of the university’s master of public administration program, provide an opportunity to recruit for programs held at Cheyney Center City where “the focus is on degree completion,” she says.

Concentration on this metric seems wise, given that, for example, on the Chronicle of Higher Education’s “College Completion” microsite, the state of Pennsylvania’s 2010 four-year graduation rate for public colleges and universities was only about 40 percent. Further, in Philadelphia alone, it’s estimated that there are more than 70,000 adults who have at least one year’s worth of college credits but have not completed their degrees.

Previously, the university’s primary degree program for working adults was designed to help teachers become principals. Parker says the move to the City Center location a few years ago “was designed to attract a larger audience of adult learners in other fields besides education.”

Curriculum collaboration. The university developed a revised enrollment management plan almost three years ago in response to recommendations from the Middle States Commission on Higher Education. The overall initiative included a new business plan for recruitment at City Center to more specifically attract graduate students, nontraditional students, and transfer students.

“We felt there was a market for us,” Parker notes, “and we wanted to make it easier for students to access the university.”

Cheyney is one of four institutions co-located in the Philadelphia Multi-University Center, spearheaded by the Pennsylvania State System of Higher Education (PASSHE) and officially opened in March. Pennsylvania’s Millersville, East Stroudsburg, and West Chester universities also have a presence at the center.

According to Parker, each of the institutions agreed to an exclusivity clause, outlining the specific programs that they would offer without competing with one another for students. “We tried to vary the offerings among the participating institutions,” she says. “We worked together to provide the best possible array of programs. The idea is that students can come to one location and have access to more than one institution.”

For Cheyney’s part, the university offers undergraduate degree–completion programs in communications, business, psychology, and business administration, as well as graduate programs in educational leadership, urban education, elementary education, and public administration.

All the institutions also receive marketing support from PASSHE that supplements their own promotion and recruitment efforts, which include outreach to local employers. While Parker expects enrollment to increase at the Center City site, she says “the university will continue to evaluate the vitality and relevancy of all academic programs as reflected in enrollment and graduation rates.”

Involving industry. This kind of cooperation among institutions supports Graduate Philadelphia’s overarching mission to increase the number of adults with college degrees in Greater Philadelphia. Founded in 2005 and funded by United Way, Lumina Foundation, Texas Guaranteed, and the City of Philadelphia, Graduate Philadelphia reports that it has helped 1,900 people go back to college—and a retention rate of more than 90 percent.

Placing emphasis on degree completion not only serves the region well, but it can also be a selling point when local institutions pursue partnerships. “We definitely showcase the Center City site when meeting with potential business partners,” Parker says. “We’re trying to forge a cooperative relationship based on the needs of local industry and the needs of the institution.”

To that end, Cheyney recently enlisted Wawa Food Markets, a national company with headquarters in Wawa, Pennsylvania, to review its business curriculum and “help us identify any gaps,” Parker says. “One of our key goals is meeting the needs of industry in the region.”

Advice and Affirmation

“The starting point for us was not to assume that we knew what the problem was,” says GSU’s President Mark Becker of the university’s efforts to improve degree-completion rates and enhance support services for minority students. In 2010, more than half the student population represented minorities (32 percent African-American, 6 percent Hispanic, 10 percent Asian, and 3 percent multiracial); in 2012, the dropout rate for first-year students was 18 percent.

“We actually called students who had dropped out, and asked, ‘Why aren’t you here?’” he admits. “We’ve been humbled by talking with real students about what was keeping them out of school.”

Finances a big factor. Becker says that through such contacts, the university learned that the majority of students had left GSU because of financial reasons, rather than academic issues. That led to redesigning the institution’s financial aid structure “to give small amounts of money that can make a big difference.”

At GSU, 87 percent of students qualify for financial aid, and at least 40 percent are first-generation college students, which means they often lack the “cultural competency” to navigate the higher education system. To help them better manage the financial aspects of obtaining their degrees, GSU launched a financial literacy program last January focused on educating students about personal finance and debt management.

Programs like this one became part of a suite of support services designed to help struggling students regain their footing, understand possible funding sources, and remain at the university. For example, many of GSU’s students are eligible for the state of Georgia’s HOPE (Helping Outstanding Pupils Educationally) Scholarship, which covers a large share of their tuition costs—close to 90 percent for GSU students (percentage determined annually)—as long as they maintain a 3.0 grade point average.

“Students were losing their scholarships and dropping out,” Becker says. To mitigate this problem and help students regain their eligibility for the scholarships, GSU launched its “Keep Hope Alive” initiative, which provides students with $500 scholarships per semester and requires them to attend financial literacy and study skills classes. These scholarships are funded through unrestricted donations to the universitywide scholarship fund.

Students also receive extensive academic counseling and must complete GSU’s Academic Coaching Experience, which guides them in planning a realistic strategy for staying at the university. Academic advising is an integral component of GSU’s plan for student success. The university recently hired 42 academic advisers.

“Part of our goal was to get some consistency in how we were advising students and what we were advising them about,” says GSU’s Linda Nelson. “We wanted to make sure that even though there were various places for students to go for advising, they weren’t falling through the cracks.”

Receiving extensive counseling along with these small grants has helped hundreds of GSU students remain in school while working to regain state funding. For students in the program, more than 60 percent regain their funding. But, for students who lose HOPE funding and are not in the Keep Hope Alive program, only 8 percent regain it.

While this initiative was not specifically geared towards minority students, it serves as a model for the way GSU has approached other programs targeted on nontraditional students.

Responding to rapid growth. One particular of area of success has been improving graduation rates for Latino students. Timothy M. Renick, GSU senior associate provost for academic programs, says the university identified Latino students as one of the fastest-growing demographic groups in the region. According to the College Board’s “College Completion Agenda, Latino Edition,” Georgia ranks 10th in the top 10 states for percentage of total U.S. Latino population. Renick estimates that 11 percent of this year’s freshman class was Latino. “Some of our very first learning communities were for Latino students,” Renick says. “We’ve had these for over a decade, they’ve shown good results in student retention, and they are fairly low-cost.”

To form learning communities, GSU takes cohorts of 25 freshman students and puts them together in groups where they attend orientation programs together and build personal connections. For students who have self-identified their ethnic backgrounds, specifically joining Latino learning communities is optional, but has proved helpful.

“Our Latino students had the lowest retention and graduation rate of any minority group on campus; now they have the highest,” says Renick. “Ten years ago the graduation rate for Latino students at GSU was 22 percent; currently it’s 66 percent.”

Five years ago when the university began to focus on degree completion more strategically, the plan developed didn’t specifically target minority students. “When we committed to increasing degree completion rates, we had one plan for the university as a whole,” Becker says. “And the plans that have been adopted since haven’t been focused on race and ethnicity, but the side benefit is that we no longer have disparity in graduation rates between white students and minority students.”

A complete package. Renick credits GSU’s success in increasing the graduation rate to combining all of the university’s effective support programs into one package that evolved into the Latino Leadership Pipeline (LLP), which is designed “to recruit, retain, and graduate Latino students.”

The elements of the program include the following:

- Students from local high schools apply and compete for scholarships the program makes available.

- Once students arrive on campus, GSU’s approach to diversity includes encouraging Latinos and other minority students to be fully engaged in the culture of the campus as a whole. “I’ve seen broader involvement of students across all aspects of the university,” says Nelson, who led the development of the university’s Diversity Strategic Plan.

“Our very strong emphasis on student engagement has been effective,” she continues. “We’ve done a good job of getting minority students involved in all aspects of academic components beyond the classroom, such as our internship and study abroad programs.”

- In addition to a financial award of $10,000 per student, LLP scholarship recipients benefit from a number of support services that further increase their engagement on campus. For instance, the program includes financial literacy workshops because “these students will make financial mistakes that make it difficult for them to continue their education,” Renick says.

- Students are required to receive supplemental instruction from tutors. “We hire student tutors, as there is often reluctance to approach a professor and a better comfort level for working with a peer,” Renick says.

Those students with access to tutors eventually “sign a contract committing to tutor during their own junior and senior years,” explains Renick. “They tutor in GSU’s supplemental learning program or in local high schools with large Latino student populations.” Being the one being tutored and then becoming a tutor reinforces academic success and contributes to strong performance.

Toward the beginning of their senior year, students in the Latino pipeline are paired with alumni who serve as their mentors. Renick says, “The idea is that the graduates of the pipeline will become the next generation of mentors. We hope the pipeline will be self-replicating.”

Only in its second year and limited to 25 funded students per year, the program is designed to have an impact on a much larger group of students and has received funding of $5 million for five years from the Goizueta Foundation, which was established by Roberto C. Goizueta, the late CEO and chairman of the board of directors of the Coca-Cola Co.

At a recent luncheon honoring LLP scholarship finalists, GSU President Mark Becker said the program “helps the university advance its top strategic goal: becoming a national model for undergraduate education by showing that students from all backgrounds can achieve success.”

Thus, from his perspective, continuing to fund additional and necessary support services for students is challenging, but reasonable. “We have some increased state funding through Complete College America,” he says, “and if we collect tuition for four years instead of two or three, that puts money back into the system. Collecting more tuition dollars by increasing retention and degree completion makes sense economically; we’ve grown by 4,000 students.”

Given the changes in demographics that have resulted in greater diversity on their campuses, Becker believes GSU and other institutions must develop a different mind-set than the one baby boomers had when they were undergraduates. From his perspective, the whole “look to your left and to your right, one of you won’t be here in four years” scenario is a thing of the past.

“If we admit you, we’ve already determined that you can be successful,” he says. “The goal is that everybody will be here in four years. We expect everybody to graduate.”

APRYL MOTLEY, Columbia, Maryland, covers higher education business issues for Business Officer.