Let’s say you work for a complex institution that conducts a lot of sponsored research, engages regularly in public service initiatives, and includes a medical school and teaching hospital. Do you classify the costs associated with medical students working in the hospital as hospital expenses, or are they, in part, applicable to the institution’s educational function?

Now suppose those medical students also accompany faculty members to an area reeling from a natural disaster, to provide emergency assistance and basic medical care. Are the resulting expenses related to the university’s research, public service, or education mission—or some of each?

In the business office, even at smaller institutions, we grapple with such questions frequently, if not daily. The answers often take an autopilot approach: We assign an expense, based on where the cost was budgeted, to one of the long-standing functional expense categories and move on without further thought. If the business office replaces an air conditioner, for example, the cost is probably assigned to the institutional support category, not operation and maintenance of plant, even though the latter appears most applicable.

For decades, NACUBO’s Financial Accounting and Reporting Manual (FARM) has served as the definitive guide for assigning expenses to a primary function. Those categories have not only shaped the organization of our general ledgers and audited financial statements, but they also form the basis of institutional reporting to the U.S. Department of Education’s National Center for Education Statistics (NCES). And, while they are certainly useful, the functional expense definitions in FARM reflect how institutions of higher education were organized decades ago; they don’t necessarily accommodate the complexity of programmatic functions within our institutions today.

Campus security, for example, now encompasses far more than the protection of institutional property. IT functions, which didn’t really exist when FARM first appeared, now permeate all other functions. The existing functional expense definitions, however, don’t consistently reflect those realities.

Outside Interest Up

Perhaps because the definitions haven’t changed in years, colleges and universities have developed their own ideas of how to group and report functional expenses. That “creativity” has led to an inconsistency throughout higher education. For example, similar types of expenses may be reported by one institution as academic support and by another as instruction.

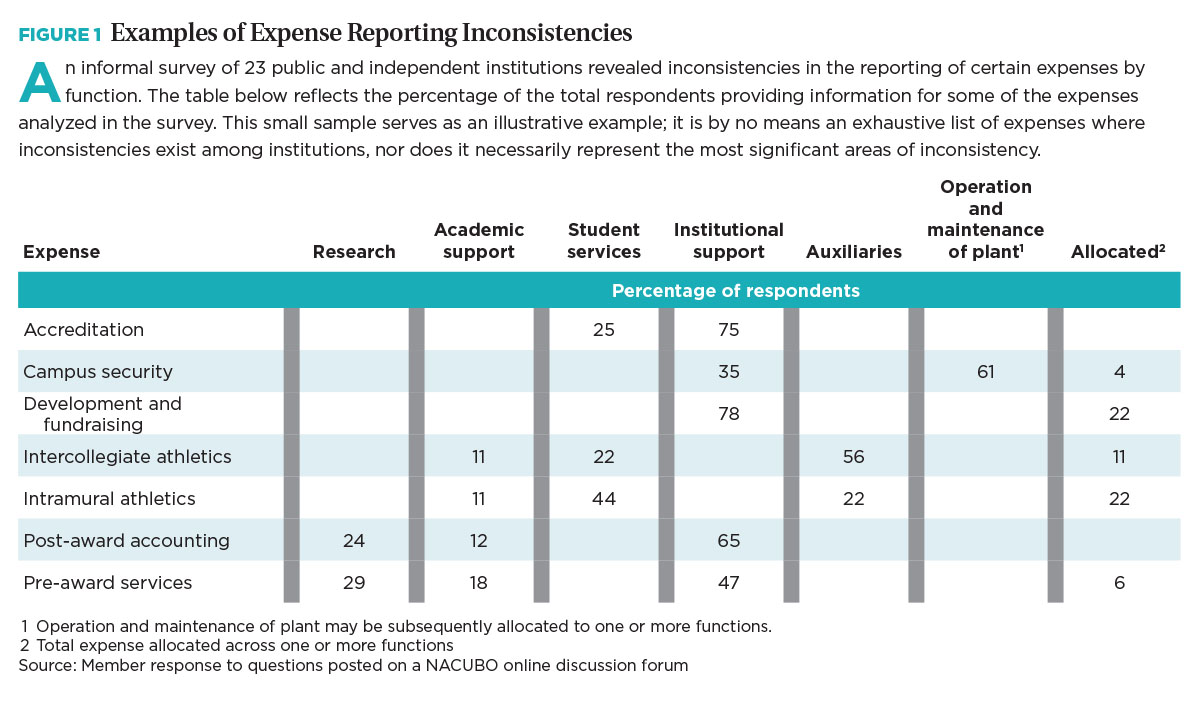

Such inconsistencies became clear when NACUBO recently conducted an informal survey on the current state of expenditure reporting in higher education financial statements. The results showed significant variances in how expenses were categorized in activities ranging from departmental research to allocation of plant maintenance, and from athletics to depreciation and interest (see Figure 1, “Examples of Expense Reporting Inconsistencies”).

Some institutions create a separate function for every programmatic activity, rather than grouping the activities under a traditional and encompassing definition. Others report functional expenses that aren’t truly expenses, such as gain or loss on disposable property.

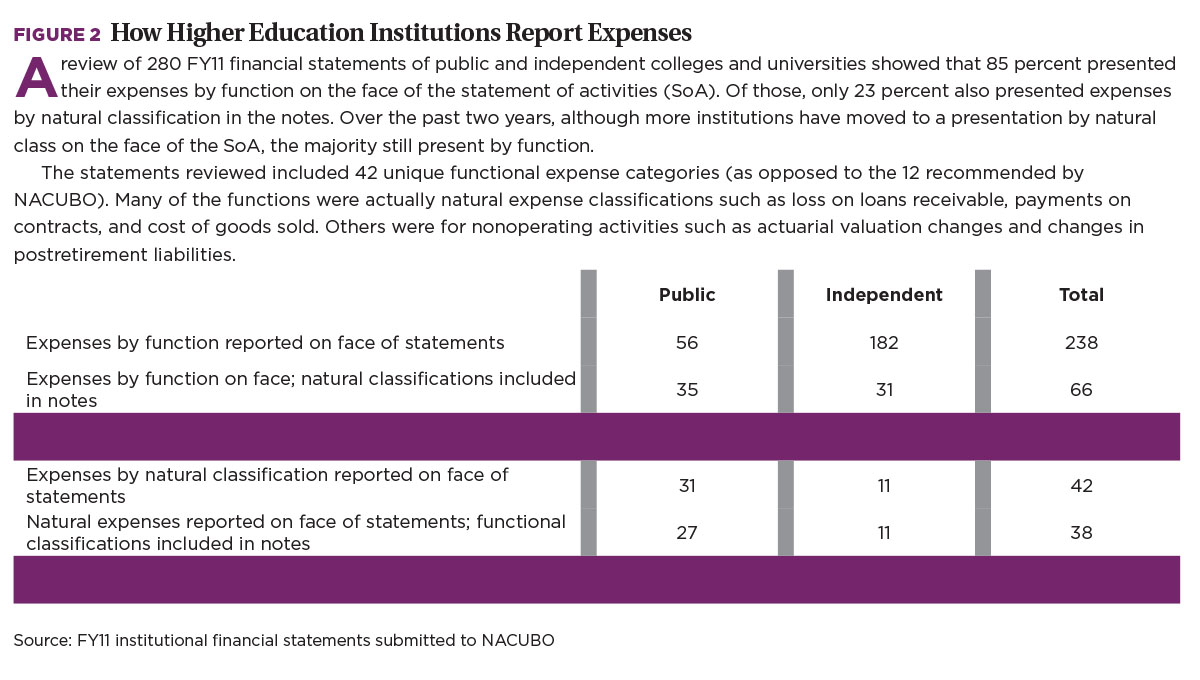

One might argue that natural classification of expenses, when shown on the face of the financial statements, proves more useful than functional classification. Board members, who have a fiscal responsibility to the institution, more readily understand natural classification, the language of the for-profit world. But higher education institutions operate within the not-for-profit (NFP) world, which has its own requirements—one of which is reporting functional expenses in the financial statements. In fact, most colleges and universities report functional expenses on the face of their statements (see Figure 2, “How Higher Education Institutions Report Expenses”). And, all independent NFP and public institutions must report expenses by function annually on the Integrated Postsecondary Education Data System (IPEDS) Finance Survey, which is administered by NCES. Finance survey information is publicly available through the IPEDS data center.

Like it or not, media outlets and increasingly, public officials, turn to the IPEDS data to gain a sense of how much colleges and universities spend on, say, administrative overhead or educating students. Thanks to the detailed breakdown IPEDS provides within the overall education and general category, users zero in on one particular function rather than looking at the bigger picture of the many functions that, taken together, support an institution’s educational mission.

Various stakeholders also use the data to compare the cost of obtaining a degree at different institutions, typically by dividing instruction expenses by the number of full-time-equivalent students. That calculation omits other functions necessary to deliver a college education, including student services, academic support, and central administration. In short, it doesn’t tell the entire story. Inconsistent functional expense classifications used by the schools skew cost comparisons as well.

Functional expense reporting is also used by research and program funders who look at the ratio of program expenditures to total expenditures when evaluating a not-for-profit’s effectiveness in fulfilling its mission. Even the Financial Accounting Standards Board (FASB) has taken a keen interest in this topic and may require an analysis of natural expenses by function in the future (see sidebar, “Preliminary FASB Decisions on Functional Expense Reporting”).

An Updated Structure

With the White House calling for greater transparency from colleges and universities, probably in the form of a financial report card, expense data will undoubtedly come under even greater scrutiny. Seemingly everyone wants to know what it costs to educate a student, and functional expense reporting can help an institution answer that question accurately—especially if higher education redefines the categories.

After reviewing the widespread usage and current limitations of functional expenses, NACUBO’s Accounting Principles Council (APC) has begun discussing the best way to update, consolidate, and streamline reporting categories. For instance, in place of the 12 categories introduced decades ago, the APC is considering recommending these six:

- Education (related activities and instruction).

- Research.

- Auxiliaries.

- Independent operations (if applicable).

- Medical centers and hospitals (if applicable).

- Public service (if significant).

With fewer categories, the expenses within each become more meaningful and contribute to greater comparability. Expenses typically included in the traditional categories of institutional, academic, and student support would be included in the function they actually support. Similarly, for public institutions, operation and maintenance of plant and depreciation would be included in the functions that those expenses support. For example, the costs associated with maintaining and operating a library would be included in educational activities. Each institution would determine how to allocate its overhead expenses to the various categories and explain its rationale to stakeholders.

Using this suggested structure, the lion’s share of expenses would rightly end up in the education category. Showing all the functions that relate to educational activities and instruction will give college students and their parents a truer sense of everything that contributes to an education, and why an institution charges the tuition and fees it does. As you’d expect, the education category for a four-year college would contain higher residential and student services expenses than those of a commuter-focused community college.

This clarity becomes possible only when an institution’s accounting and financial professionals use logical definitions for the various functions and apply them consistently. Sometimes that may mean digging into the specifics of a particular transaction and making a judgment call on how best to allocate the expenses among the functional categories.

Using the earlier example of an institution’s medical mission to a disaster area, the business office might refer to a time study done during the trip, or talk with a faculty member. Depending on the information received, the expenses might be divided among public service, education, and research activities. Although the resulting division of expenses may not be precise, it isn’t arbitrary—it’s based upon informed judgment.

As the higher education community in general considers how to change functional expense categories, NACUBO is committed to providing direction for the industry. Industry guidance will enable a coherent response to FASB’s recommendations and encourage consistency in the way both independent and public institutions approach telling their programmatic story through functional expense reporting. To better reflect the complexity of today’s operations and assist NACUBO with future guidance, individual institutions can implement the following recommendations now:

- Acknowledge the importance of functional reporting to external audiences. Numerous stakeholders have an interest in IPEDS data, which each uses in a different way—often for purposes of comparison among institutions. Because of this widespread usage, the functional expenses reported to the Department of Education should be both accurate and clearly explained.

- Use NACUBO’s FARM as a starting point. Although the expense definitions the manual offers haven’t been updated to reflect pure core program functions, FARM still provides guidance to any institution seeking to define or refine function codes. Does it make sense, for instance, to combine instruction, student services, academic support, and departmental research into one functional category of education, plus an allocation for maintenance of plant, depreciation, institutional support, and so forth?

- Explain your institution’s definitions in financial statements. Because combining a number of existing functions into one may hamper comparability, a clear explanation of what’s in the functions is critical. Use footnote disclosures to communicate the types of expenses within each category, including the allocation of overhead. For example, the category of independent operations might include a power plant at one university and a hotel at another. You might spell out how plant maintenance and depreciation are allocated to the auxiliaries category—say, based upon square footage of the auxiliary facilities. Provide enough detail that readers understand how your institution’s categories differ from those of other institutions.

The functional categories may be the same for all institutions, but each one can customize those categories to tell its unique educational study.

KARL TURRO is controller, Northwestern University, Evanston, Illinois.