Will you have enough income to support a comfortable retirement?

A majority of Americans (59 percent) say they are “very” or “moderately” worried about their level of retirement savings, according to Gallup’s 2014 poll on the economy and personal finance. That finding has topped the annual poll’s list of financial concerns, in both good and rocky economic times, every year since 2001.

Even college and university business officers, who spend their careers dealing with finances, worry about their personal cash flow once the regular paychecks stop. “My husband and I had prepared well, and I was rationally confident that we would be well-positioned in retirement,” reports Mary Jo Maydew, who retired as vice president for finance and administration at Mount Holyoke College, South Hadley, Mass. “But, however comfortable the numbers suggest you will be, it’s still daunting to leave the security of a salary.”

Facing the Uncertainties

Working with a financial adviser to review payment options from your institution’s retirement plan can bring some peace of mind, notes Douglas Rothermich, managing director of wealth planning strategies for TIAA-CREF. You might be pleasantly surprised to see what resources you have accumulated.

Ideally, throughout your working years, says Rothermich, you and your adviser focus on financial planning related to investments, retirement savings, and estate planning. He adds, “Then, a year or two before you’d like to retire is the right time to get down to specifics, such as lining up your anticipated expenses in retirement against your likely sources of income, and looking at each detail for your postretirement financial life.”

That’s exactly what Tom Kingston did, sitting down with a financial and life planning adviser about five years before he thought he’d like to retire. “With the adviser, I charted cash flow over the coming years, identified all the sources of income, estimated annual expenses over time, and looked at the risks and benefits of investing in certain asset classes—just like we would for a university’s financial plan,” says Kingston, vice president for finance and administration, emeritus, at Franklin & Marshall College in Lancaster, Pa.

In addition to working with an objective, outside expert, Kingston recommends giving yourself the benefit of your own expertise. “Plan ahead for yourself like you would for your institution, and don’t try to do it out of your back pocket,” he suggests. “Take a day off, with no one around, and plan as if you were buying a business or entering a new career—which you are.”

Two years before he retired, for example, Kingston sequestered himself at home for a few days to review assets and plot out potential retirement income and expenses. For the most part, he assumed that he and his wife would maintain the same lifestyle, with the addition of more travel for the first 10 years after retirement.

“I pushed and shoved those numbers, just like we do for our institutions: What if this happened? What if that happened instead?” recalls Kingston. He ended up with a seemingly workable plan that met his goals of not taking Social Security or drawing heavily on retirement savings until the age of 66. And the plan did work, even though Kingston retired at age 63 in 2008, just as the bottom fell out of the market.

The recession also gave a bit of a scare to Carol Campbell, who had planned her retirement for 2009, from Arizona State University (ASU), Tempe. Throughout her career she had run many retirement planning simulations, and not one had anticipated the events that unfolded in 2008. “What kept me on track for retirement in 2009 was knowing we could live on Social Security and my husband’s pension for another five years, which would give the market time to stage a recovery,” remembers Campbell, who had served as ASU’s executive vice president and chief financial officer. “Fortunately, here we are six years down the road and our overall plan has worked.”

Easy Does It

Campbell admits the decision to retire was difficult. “That’s probably true for all business officers, because we love our institutions and we love our jobs. Plus, we tend to have a bit of ‘control freak’ in us,” she observes wryly. In fact, NACUBO’s 2013 National Profile of Higher Education Chief Business Officers reports that the overwhelming majority of CBOs, approximately 90 percent, are either “satisfied” or “very satisfied” with their current position.

Nevertheless, Campbell’s husband had been patiently waiting for her to join him in retirement, and she realized the time for doing everything they had dreamed about, while still in good health, could start slipping away. “Also, I knew from the four career moves I had made that I certainly was not irreplaceable and that the institution would thrive after I left,” Campbell adds. “The last transition—to retirement—was far more flexible than the others and actually the easiest for the institution, because I wasn’t going anyplace right away.”

Campbell made her ‘soft announcement’ to ASU’s president about one year before she planned to retire and agreed to stay until the search for a new CFO had concluded. In the end she worked an additional 18 months, several of them after her successor had arrived on campus.

“I’d been working on some projects that needed somewhat of a heavy hand, and we all agreed it would be best if I stayed on to complete them. Then my replacement didn’t have to do some potentially unpopular things right off the bat,” says Campbell. “That transition time also worked beautifully for me because it became like a phased retirement.”

Maydew took a similar approach at Mount Holyoke, although her gradual transition to retirement spanned about eight years. A serious health crisis in her mid-50s had prompted Maydew to improve her work/life balance. In 2004, with the president’s full support, she had begun working four long days per week and blocking out a fifth day to be out of the office—and she remained disciplined about not working on that day off.

As a result, Maydew had already moved mentally and professionally toward retirement several years before it occurred. “I had taken a hard look at my schedule and how I was spending my time. Then I off-loaded anything I didn’t need to be doing and became more efficient when I was in the office,” she says.

At the time Maydew retired in 2011, Mount Holyoke had not only a new president but also was in the midst of a major strategic planning process. The president asked Maydew to work one day a week for the next year, primarily to complete her work with a task force and some policy development initiatives. When Maydew’s successor was hired, he asked her to take on several additional tasks, including writing the narrative to the financial report.

“In our meetings, I’d talk through the history and politics of various issues, which helped him get up to speed,” recalls Maydew, who also sorted through piles of files dating back several decades. “That was a luxury,” she says, “because it gave us the opportunity—which you usually don’t have with a transition—to make sure all the files were in good order, organized, and up-to-date.”

During her one-year extension of service to the college, Maydew intentionally worked from home rather than on campus, pulled back from role-based relationships, and went only to meetings that pertained to her projects. “Because I wasn’t a constant presence on campus, the staff did not have the temptation to turn to me instead of my successor—which would have been completely natural but not a good thing,” says Maydew, who had spent 25 years at Mount Holyoke.

Filling In

Before retiring, Maydew thought she might like to work as a consultant or interim administrator. After trying the first option in retirement, she decided not to pursue either path. “While I enjoyed the individual consulting assignments, they were too much like work—other people’s timing, other people’s deadlines,” she says.

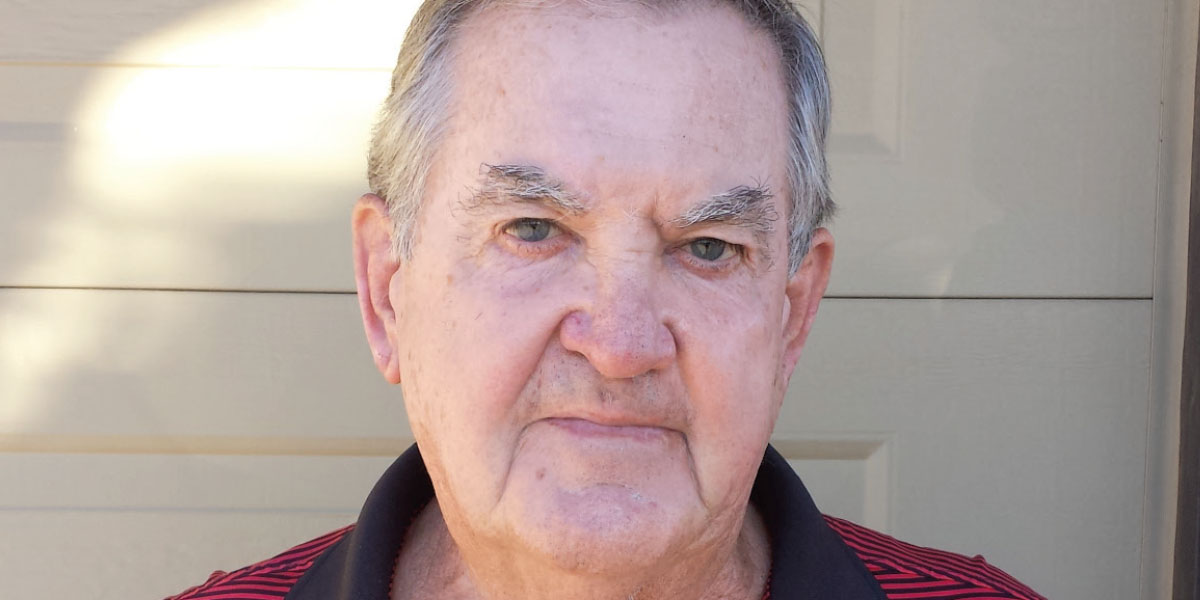

In contrast, Bob Lovitt has enjoyed consulting work, as well as two interim assignments, in retirement. He first retired as senior vice president of business affairs at the University of Texas at Dallas in 2005 and then, three years later, as executive vice president for finance and administration from Texas A&M University–Corpus Christi.

“Higher education has been very good to me, and I wanted to give something in return,” says Lovitt, who focuses his consulting work on organizational structure. He recently completed a stint as interim vice president for administration and finance at California State University, Dominguez Hills. For Lovitt, the nine-month interim assignment entailed working four days per week on campus and commuting to his home in Texas for a fifth day of work and the weekend.

“Interims are exciting positions because, if the president gives you the authority, you can make the changes in personnel or operations that are best for the university and really see the progress,” observes Lovitt, whose responsibilities at Dominguez Hills included serving on the search committee for the new CFO. “As an interim, I have made some drastic changes and then taken the heat so the new person coming on board didn’t have to deal with so much.”

“Being an outside person,” adds Tom Kingston, “you bring a whole new perspective to the president and other people in the cabinet. That can help an institution know what it wants in a new VP while the search is going on.” He has held three interim positions as vice president of finance in the past five years, the longest lasting 12 months. From the personal perspective, he adds, “Interims give you the opportunity to immerse yourself in a place, become a part of it, and use your years of expertise to be an idea facilitator.”

Kingston accepted interim positions at institutions located within a 90-mile drive so he could always spend weekends in his own home. Such geographic proximity is a key consideration if you might like to serve as an interim administrator in retirement, says Joseph Johnston Jr., senior consultant for administration at AGB Search, Washington, D.C. Otherwise, you might spend a lot of time commuting or even need to relocate.

Johnston, who conducts cabinet-level interim searches on behalf of institutions, offers other factors for retirees to consider before accepting a short-term position. For example: What specifically does the institution expect you to accomplish? Are proposals for transformational change welcome or reserved for the incoming CFO? Will you have the full support of and access to the board or president?

“You also need to be alert to the political realities, such as people who may be skeptical about your knowledge of or commitment to the institution,” notes Johnston. Even so, serving as an interim can provide you the satisfaction of helping an institution needing leadership continuity—and of generating additional retirement income.

Countdown to the Big Day

Whether your target date for retirement is two years or 10 years away—or still undecided—these tips can help you prepare for the transition:

- Work with a financial adviser. Many institutions offer advisory services through their retirement plans. If your institution doesn’t, hire your own adviser to raise all the financial issues you’ll need to consider, including income flows, asset allocation, health-care coverage and directives, and estate planning.

Lovitt began meeting periodically with a financial adviser about 10 years before retiring. “I relied on my adviser to present options and suggestions because he makes a living doing financial planning,” notes Lovitt, who had a defined contribution plan. “I followed his recommendations, and it worked out well for me.”

- Ready your real estate. “Five years before I thought I might retire, we started renovating and updating our house. With all those big projects done, including the kitchen and bathrooms, we could enjoy them and sell the property for more, later on,” says Kingston. In addition, Kingston refinanced his main residence and vacation home to 15-year mortgages so they would be paid off before his anticipated retirement date.

- Take a test run. Once you have estimated your income and expenses in retirement, try living within those means. “While the paychecks are still coming in, act like you’re retired—see how you can live off the income that would be generated in retirement,” suggests TIAA-CREF’s Douglas Rothermich. “If it’s not working smoothly, then restructure your plan. With this approach, you won’t have as sudden or abrupt a financial transition when you do retire.”

- Start with a clean slate. Mary Jo Maydew deliberately organized many of her professional and charitable commitments to conclude about the time she retired. “That gave me a chance, in the first few years of retirement, to try some new things and see if I liked them,” she explains.

- Change it up. What have you always thought about doing that’s unrelated to your career activities? Once retired, Carol Campbell started hiking more, reading through the stack of books she had accumulated over the years, and catching up on the past 20 years of Academy Award–winning movies, to name just a few items on her “bucket list.”

Maydew had always thought about teaching, so as a retiree she jumped at the chance to co-teach a course on nonprofit business at Mount Holyoke. While she thoroughly enjoyed the classroom experience, Maydew was not as enamored of the rigid, three-days-a-week teaching schedule, which began to conflict with other activities that she wanted to pursue.

In addition to coordinating a mentoring program for EACUBO, for example, Maydew serves on the boards of the local hospital and two institutions of higher education. “Governance work is a way for me to stay connected to higher education and continue being useful, just in a different role,” she observes.

Kingston, too, serves on a private school’s board and on the investment committee of a community foundation. “The best part of being a volunteer,” he jokes, “is that if you don’t like your boss you can just leave!”

- Revise as retirement unfolds. In retirement, your income may have limits but your freedom doesn’t. “If something doesn’t work out or you get tired of it, just do less of it or try something else,” advises Campbell.

Maydew, for one, is learning to say no more often, especially if she feels that volunteer commitments are pulling her life out of balance. “Sometimes activities overlap and I’m busier than I want to be,” Maydew says, “but I’m trying to be disciplined about looking at my priorities and easing out when necessary.”

You’ll probably need to adjust your financial picture, too, because retirement has its own economic cycle. As Rothermich explains, “Early on, you may have a lot of discretionary expenses related to things you’ve wanted to do for a number of years, such as traveling and perhaps purchasing a vacation home. Over time, as we age and become accustomed to a retirement lifestyle, those expenses often decline—usually to be offset by increased costs of health care and day-to-day living.”

With six years of retirement now behind her, Campbell points to only one thing she would have done differently to prepare: She would have worried less.

“Your planning is never perfect because there are so many things you can’t know in advance,” Campbell observes. “In retirement, you just get more comfortable with the fact that you still don’t know how everything will work out—and in the meantime, you enjoy life.”

SANDRA R. SABO, Mendota Heights, Minn., covers higher education business issues for Business Officer.