Today’s challenges confronting higher education are stretching the role and responsibility of the chief business officer beyond that of the traditional finance and operations guru. Tomorrow’s CBOs will be greeted with greater demands for enterprisewide innovation and progressive leadership responsibilities on increasingly diverse campuses that are redefining the higher education model.

According to NACUBO’s 2013 National Profile of Higher Education Chief Business Officers, considerable turnover of this key leadership position is anticipated over the next several years, with 40 percent of CBO survey respondents reporting that their next career goal is a transition into retirement—and with most of those citing plans to retire within the next four years.

With a growing number of prospective retirements in the forecast, what is the state of the higher education CBO talent pool for 2020 and beyond? A lack of concerted succession planning in recent years and the resulting pipeline shortages from within higher education point to underpreparedness of the next-generation CBO that will likely necessitate expanding the search for future CBOs outside the academy.

More should and can be done to build a stronger pipeline of CBO talent from within. This must happen through a combination of sitting CBOs identifying up-and-coming leaders to cultivate, and emerging leaders taking charge of their personal and professional development needs within the context of a higher education environment that is continually changing and increasingly demanding higher-level leadership acumen.

To establish a data-driven approach to CBO professional development, I conducted research that became my dissertation, A Leadership Competency Study of Higher Education Chief Business Officers, which established quantitative evidence specific to CBO meta-competencies. I have continued to build on that research to better understand the competencies and leadership development required to fill the CBO role (see sidebar, “What Aspiring CBOs Should Know”). The research efforts included a supplemental survey instrument in the NACUBO 2013 CBO profile study, along with qualitative focus groups conducted with NACUBO constituent councils and a focus group of college and university presidents at the American Council on Education’s 2013 annual meeting.

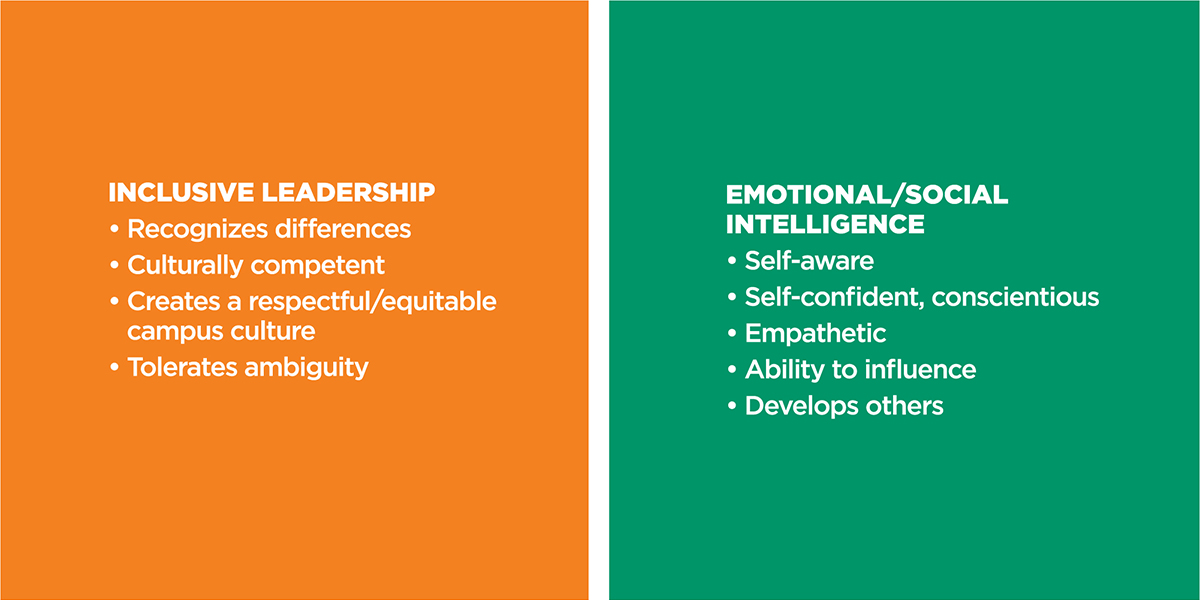

The empirical results providequantitative and qualitative evidenceabout competencies and professionaldevelopment needs of the CBO rolethat are further discussed in thisarticle. The leadership competency study concludes that the most effective CBOs rise beyond threshold competencies oftechnical proficiency and knowledge of accounting, financial management, and budgets. These skills, while important, minimally qualify tomorrow’s CBO. In fact, findings of the study suggest that the emergent CBO must focus on broader meta-competencies consisting of: (1) strategic leadership, (2) organizational engagement, (3) inclusive leadership, and (4) emotional/social intelligence.

Mastering the Meta-Competencies

Chief business officers, arguably more so than other key positions, are continuously responding to changing external requirements and to internal stakeholders. Changing expectations have catapulted the CBO from the back-office, numbers-only, technical expert to a key strategic spokesperson and campus advocate. The growing expectation that CBOs must progressively add value to every aspect of their role is daunting, and necessitates a continual focus on self-awareness and learning.

The willingness to learn, apply, adapt, and continually build on individual competencies eventually leads to the development of meta-competencies. This happens as individuals come to understand themselves and embrace the continual evolution of skills, behavioral characteristics, and traits that transcend mere proficiency and effectiveness to achieve sophisticated expert knowledge. Prior on-the-job experiences and focused competency development serve as preparatory training and an entree to a higher performance level. Multifaceted competency proficiency, professionally mature judgment, and sophisticated leadership expertise prepare the CBO to successfully oversee comprehensive facets of campus activities that are complex and robust.

Because the CBO’s portfolio of responsibilities is progressively growing into other areas such as campus innovation, economic development, and the creation of entrepreneurial business models, mastery of the meta-competencies is invaluable to an institution’s president and other campus leaders.

Strategic leadership. Effective business officers are strategic campus leaders. Strategic leadership competencies suggest a focus on the entirety of the organization, such as the development of institutional plans, complex problem solving, leveraging resources, creating teams to execute strategy, and leading or guiding change. Strategic business officers portray a wide realm of institutional thinking such as broad and forward-looking perspectives, overall demonstration of effectively leading people within and outside the organization, and the ability to build relationships and create or guide long-range vision.

Additionally, a differentiating comp-etency is strategic communication, which deepens the breadth of leadership by engaging various audiences and stakeholders through listening and collaboratively sharing information. Strategic business officers recognize the importance, and practice the mobilization of communication and use consistent messaging to drive results.

Organizational engagement. Business officers must possess a comprehensive institutional knowledge supported by fostering relationships and partnerships across a range of institutional stakeholders. A three-pronged approach is most effective: (1) understanding and adeptly communicating the campus culture and subcultures that exist across the organization; (2) understanding and advocating the president’s vision of the institution within the local, regional, and statewide environment; and (3) understanding the impact of national and global trends on the institution’s current and future state.

Chief business officers enhance their effectiveness by demonstrating a broad understanding of all higher education systems, including the legislative context in which their institutional Carnegie classification exists. These interconnections establish a rich perspective and understanding of the campus mission within the context of the entire higher education sector and with emerging trends impacting institutional mission.

CBO effectiveness is further enhanced through advanced knowledge of all campus segments such as academics, student affairs, technology, research, advancement, and athletics. A comprehensive knowledge of the contemporary higher education sector combined with broad internal perspectives informs the CBO’s role and serves to foster organizational engagement.

Inclusive leadership. Business officers who practice inclusive leadership possess the skills to navigate a diverse society, and they inherently understand that organizational excellence stems from recognizing and respecting individual and group differences. Inclusive leaders project a willingness to practice open-mindedness by creating open dialogue, listening to different perspectives, and welcoming backgrounds different from their own. Inclusive business officers have the ability to create campus systems that support an institutional culture that others recognize as welcoming, respectful, and equitable. Inclusive business officers are committed to being culturally fluent, leading equitable practices, and guiding respectful campus operations.

As university citizens, a CBO’s daily activities should include outwardly visible communication and actions that demonstrate that it is every employee’s responsibility to promote a workplace that fosters inclusion of its entire people and their respective ideas, and that encourage everyone on campus to perform at the highest level.

Emotional/social intelligence. Effective business officers practice the ability to manage themselves and others using what psychologist Daniel Goleman refers to as emotional intelligence (Emotional Intelligence at Work: Why It Can Matter More Than IQ, Bantam, 1995). This includes the capacity for self-awareness and self-management and the ability to manage others using relationship awareness and relationship management.

Self-awareness includes an ability to practice self-reflection and develop a realistic self-knowledge of strengths and weaknesses and an awareness of leadership self-image or impact. Self-management builds on self-awareness by noticing what is happening around you and attentively managing yourself via emotional self-control, conscientiousness, initiative, drive, outlook, and adaptability to complex situations or obstacles.

Relationship awareness includes an ability to empathetically tune in to others across the campus, relate to their emotions or concerns, and act responsively to their needs. Relationship management is the practice of relationship skills such as influence, persuasion, motivation, and team building.

Extensive research concludes that IQ and technical skills are insufficient predictors of leadership and that emotional intelligence is the most effective driver for leadership effectiveness.

Leadership Acumen

These four meta-competencies in fact represent a host of subcompetency characteristics and traits, some of which can be seen above in the fact boxes above. A wide body of academic and business literature, including the results of the CBO leadership competency study, concludes that a deep understanding and study of leadership is paramount to the overall effectiveness and success of the chief business officer.

CBOs must demonstrate leadership knowledge, principles, practice, and role-modeling at all times. Furthermore, they must possess high ethical standards and integrity, proficient knowledge of leadership concepts, and the innate ability to represent themselves as leaders.

Creating a shared vision and guiding others to buy in to the institution’s leadership direction with appropriate goal-setting and execution of the campus strategy is a key component of being an effective cabinet-level leader. Leadership savvy includes inspiring and influencing others to lead and to follow with innovation, creativity, and aspiration for organizational excellence.

The most effective CBOs possess leadership presence and style and, when combined with other emotional intelligence skills, facilitate collaborative partnerships and teams that likewise spur creativity, innovation, and overall positive energy for the institution. Effective leaders are also able to recognize emerging trends that impact higher education and manage those trends to drive change throughout the campus and beyond.

The President’s Perspective

With this high level of leadership acumen described thus far, it should come as no surprise that campus presidents rank strategic leadership as one of the most important leadership competencies of an effective CBO.

The qualitative evidence collected in this study suggests that CBOs are strategic partners not only to the president but also to the board, cabinet, and various professions or academic disciplines across the institution. Institution presidents need CBOs to add value at every touch point, act with integrity, and embody characteristics, competencies, and traits that portray them as trustworthy campus and community leaders.

Examples of strategic leadership statements and themes that emerged from the presidential focus groups indicate that the CBO is expected to:

- Provide historical perspective (where applicable) and look across the institution and weigh conflicting pressures and tensions in developing options that help implement and execute the vision.

- Deeply understand the core mission of the institution and play an important role in leading strategic change.

- Collaboratively identify the life-cycle costs of innovative and viable solutions (such as technology enhancements, innovations, new service models).

- Teach campus stakeholders about complex cost models, financial information, and operational plans.

- Think strategically with an entrepreneurial mindset and serve as an “early warning signal” to preserve the long-term health and viability of the institution (regarding revenue diversification, less reliance on public resources, new business models, and so on).

Additionally, presidents agree that organizational engagement is essential. Engaged CBOs demonstrate leadership and political savvy by establishing and maintaining effective relationships with the entire cabinet. In particular, presidents overwhelmingly suggested that CBOs must have a stellar relationship with the chief academic officer. The CBO and the CAO are both empowered and most effective when they work together and are perceived as a team. In building relationships with faculty, one president suggested that effective CBOs are seen as “bicultural”—that is, they demonstrate an understanding and ability to communicate with and operate effectively among the varied administrative and academic entities that exist within the academy.

Specifically, they exhibit not only an ability to teach the complex inner workings of campus operations and technical data to a community of scholars, but also a capacity to graciously learn from the expertise of their academic colleagues. They also embrace shared governance and consultative decision making.

Furthermore, presidents indicated that CBOs must effectively champion the mission-driven, distinctive academic and student-centered culture of the institution and must educate others about the institution’s complex role within its own region and globally. These important responsibilities require the CBO to effectively blend information from across each segment of the campus community, and to support and/or deliver the institutional story to the board and a broad range of communities at large.

The CBO as Change Leader

“The situation in which colleges and universities find themselves at the moment is indeed different.” This statement, taken from an article by Rita Kirshstein and Jane Wellman (“Technology and the Broken Higher Education Cost Model: Insights From the Delta Project,” EDUCAUSE Review, September/October 2012), reflects a higher education sector in the midst of dynamic and unstoppable change.

There is no doubt that disruptors and transformation are occurring in all dimensions of education including the business model, service delivery mechanisms, pedagogy, learning methodologies, transportability of credits, and time to degree. Increased regulatory pressures, growing governmental demand for accountability, and impending environmental changes necessitate that business officers evolve to meet rapidly changing institutional needs.

In The Innovative University: Changing the DNA of Higher Education From the Inside Out (Jossey-Bass, 2011), authors Clayton Christensen and Henry Eyring argue that to survive and flourish, strong and stable universities must build on, not abandon, what they do best; however, leadership must confront the escalating disruptive innovation and strategically drive change. Now more than ever, CBOs have an increasingly important role in anticipating the future and advising the president and other senior leaders about business models and complex administrative activities that must guide tomorrow’s campuses.

Some research suggests that to address the internal and external demands placed on contemporary postsecondary institutions, there is a high sense of urgency needed for institutions of all sizes to develop diverse and qualified CBOs who possess the leadership skills necessary to effectively lead wholesale change. Presidents, governing boards, and accreditors are demanding more from senior leaders as the higher education sector faces pressure to enhance institutional accountability and transparency in areas such as the fiscal impact of changing student enrollment patterns, capital and operational budgeting, and endowment management, to name a few.

Many campus strategic plans infer that the current state of higher education is more competitive and complex, and the operating rules, culture, and expectations for CBOs are markedly changing, creating new expectations at the senior levels. In her book On Being Presidential: A Guide for College and University Leaders (Jossey-Bass, 2011), Susan Pierce suggests: “To be effective, presidents need colleagues in senior positions who do in fact think institutionally, not functionally, and who think and act strategically rather than just tactically. In other words, these vice presidents and deans need to approach all problems as if they were the president, charged with the well-being of the entire institution and not just the areas for which they are formally responsible.”

Opportunities for Those Aspiring to Be CBOs

Cumulatively, the current state of the higher education sector suggests that increased leadership from within the academy is necessary to move postsecondary education beyond these disruptors and to usher in a new period of innovation. The data suggest there are important evolutions in the ecosystem of a CBO’s professional learning that can enhance value-added contributions to the campuses they serve.

For instance, consider that NACUBO’s 2013 CBO Profile found that the average sitting CBO is a 56-year-old white male, married, with an advanced degree and an average eight-year tenure in his role. An overwhelming majority—approximately 86 percent of respondents—self-identified as white and only 11 percent as people of color. One obvious implication these CBO demographics suggest is that there are growth opportunities for women and people of color in particular to prepare for CBO roles.

Likewise, CBO learning models and campus succession plans must cut across talent pools in order to build a stronger bench. Leaders within the academy and organizations that support professional development are at an opportune time to identify and cultivate a diverse pool of prospective CBO talent that can champion and lead the future of higher education. This suggests that future CBOs may increasingly come from other disciplines beyond the traditional finance and accounting professions.

While the leadership competency study suggests that there is significant commonality for CBOs across a variety of technical competencies and leadership concepts, among the various constituent groups that comprise the American higher education sector, there does exist some nuance based on institution type. The following summarizes themes expressed by 40 percent or more of the CBO respondents within the study focus groups.

- Small institutions. CBOs in this group were focused on future thinking and long-term sustainability. These CBOs suggested that they must ably forecast with new market considerations such as growing competitors from the for-profit higher education sector and with the new product offerings of other institutions such as robust online models.

- Community colleges. CBOs in this group were focused on flexibility and adaptability with an emphasis on having the capability to act quickly. This constituency suggested that CBOs must have the ability to evaluate and assess multiple situations and/or problems, and promptly prioritize and resolve matters without overreaching.

- Comprehensive-doctoral and research institutions. CBOs in these groups had similar perspectives, as they were focused on operational management across a wide breadth of services and expertise, including a wide range of enterprise units such as professional schools, hospitals, and research centers. This cross-sector of CBOs suggested that they must have a broader knowledge base about a larger number of areas, consistent multimodal communication, and the capability to manage operations comparable to small and midsize cities.

All CBO groups agreed that communication about business operations using terms and comparisons that campus stakeholders can understand is a critical common factor. However, sophisticated strategic communication was more readily expressed by CBOs in the research and comprehensive-doctoral groups.

In the near term, there will be a growing number of CBO vacancies within each constituent group, and the adaptability and experiential base of the prospective candidates will influence their success to cross over to other institutional types. One president referred to this as “glass partitions,” suggesting that some silos exist that may make it more difficult for a CBO to move from one type of Carnegie-classified institution to another.

The Bottom Line on Competency Development

Foremost, CBOs are strategic leaders capable of collaboratively developing progressive financial plans, managing complex operations for a wide span of critical activities to ensure that institutional functions advance the goals of the president and the mission of the institution. While CBO leadership will never be an exact science, neither should it remain a mystery to those higher education leaders who are in or who aspire to fill this essential role in the life of the institution. Research has helped identify the competencies, behaviors, and skills that affect job performance. Through this research and a growing body of evidence, higher education leaders also have an enhanced understanding of what competencies are necessary to lead effectively within the future state of the academy.

The alignment of personal learning plans with competency gaps and the development of mentor-protege relationships or pursuit of professional sponsors can be useful for aspiring CBOs. Sitting CBOs must likewise reassess their professional development to respond to a higher education environment that is continually changing, even as they are identifying the next generation of talent to cultivate and mentor.

The CBO of tomorrow is a resilient, continually learning, campus leader who will help guide and steer the viability of our institutions well into the future. Day to day, week to week, and from one academic year to the next, effective business officers must continually hone their leadership competencies and adjust their leadership styles to employ the right one, at the right time, and in the right measure.

CYNTHIA TENIENTE-MATSON is vice president for administration and chief financial officer, California State University, Fresno. As a former NACUBO Board of Directors chair, she explored CBO competencies in her doctoral work and continues research pursuits in CBO leadership and diversity.