The University System of Georgia (USG) is one of the largest and most complex higher education systems in the United States. Our 30 public colleges and universities enroll more than 312,000 students. Five years ago when asked, “What keeps you awake at night?” USG’s then–chief administrative officer Rob Watts’ responses became the impetus of a systemwide talent management initiative.

His first response was related to the budget and the ubiquitous effects of the 2008 recession that lingered in 2010. He then revealed additional concerns about the impending retirements of a significant number of our incumbent CBOs. Since his assessment was that the system lacked a cadre of leaders that was prepared to assume these critical positions, he suggested that we deem this issue as an institution priority. Given the predicted mass exodus from higher education and other sectors, it was clear that we needed to focus on the development and preparation of executive leadership within all parts of our institution.

The demand for all organizations to value and focus on people is rapidly increasing. Research by E.E. Lawler, in Talent: Making People Your Competitive Advantage (Jossey-Bass, 2008), indicates that decisions about people should be made with rigor, logic, and precision, and to do anything less jeopardizes the effective performance of the enterprise. And, like many other public and private institutions, USG continues to encounter challenges to attract, develop, and retain talent at a time when skilled staff are most needed. We knew that we needed to develop and institute a strategic approach to talent management, particularly in identifying and preparing emerging leaders to transition into the CBO position.

It was also obvious that we could align such work with USG’s strategic plan goal “to increase efficiency working as a system by promoting from within the system to fill leadership positions and by reducing expenses associated with external recruitment at each institution.”

Consequently, we set out to create a formalized talent management plan to fill our leadership gaps from within our own system. Early results are positive, but it has taken a huge amount of effort and fine-tuning along the way.

Facing the Facts

The University System Office of Human Resources Organizational Development has been responsible for spearheading talent management and leadership development initiatives in the USG, since the department’s inception in 2008. In 2010, systemwide retirement data indicated that nearly 40 percent of our incumbent CBOs were eligible to retire within the next five years. This anticipated turnover was the impetus to further focus our efforts on the CBO position.

This trend was particularly disturbing to senior leaders for several reasons:

- Some of our institutions are located in geographic areas of the state that pose a challenge for recruiting and retention of top talent. Additionally, research indicates that finding leaders with the right cultural fit and requisite skills is difficult.

- Our hiring processes were reactive, cumbersome, and transactional. This resulted in vacant CBO positions, a trend that threatened business operations and leadership continuity on our campuses.

- Expenses related to the use of external search firms averaged $20,000 to $30,000 per executive position.

These factors called for a strategic approach to talent management and supported the system’s ongoing effort to build a culture of leadership excellence. A strategic and integrated approach to talent management would help develop a diverse internal pool of committed leaders prepared to ascend to the CBO role. Furthermore, such processes would ultimately engage and retain the system’s top talent.

Senior management commitment is critical to such systemwide change efforts. Chancellor Henry Huckaby and the chief administration officer, Steve Wrigley, championed the effort by communicating key messages and milestones, as well as by allocating resources and recommending best practices to support the progress of the talent management initiative. A new vice chancellor, Marion Fedrick, came aboard in 2012 and fully supported a strategic approach to enterprisewide talent management and employee development. Other senior leaders, such as vice chancellors of planning, academic affairs, internal audit, and legal affairs, engaged in the study and provided helpful feedback at various points during the process. Internal conditions were ripe for the vital change necessary to institute a strategic and integrated talent management system.

Interest in this initiative gained momentum when we contacted chief human resources officers (CHROs) from each institution group—all of whom possessed extensive management and human resources experience—to discuss the issue and to extend an invitation to participate on a team to address talent management issues, in particular the CBO position.

Prior to our initial meeting, we requested recommendations of CBOs who could advise the team of CHROs and invited three incumbent CBOs to participate as advisers. With a knowledgeable and highly enthusiastic team and advisory group established, we planned the first of many meetings to begin tackling the CBO talent crisis in the USG.

Where to Begin?

Recognizing that we could only effectively bite off one piece at a time of this enormous task, we initially sought to define a reasonable and feasible project scope. Given the size of the USG, we decided to work initially with CBOs who were geographically accessible; willing to take on additional responsibilities associated with this study; and represented different institution groups: research universities, comprehensive universities, state universities, and state colleges. We ultimately identified 13 CBOs who participated in the pilot phase of this study.

The team conducted a benchmark study of higher education systems and institutions, and findings suggested that few higher education institutions had implemented comprehensive talent management processes. This finding was consistent with our team’s general knowledge that higher education had been slow to adopt management practices, such as talent management, that had proven effective and efficient in businesses. We also acknowledged that management practices that work well in private companies do not unilaterally apply in higher education. We intended to invest resources wisely due to industry criticism that talent management practices in general were time-consuming, expensive, and disruptive.

Because of the increasing complexity and evolution of the CBO role, the team agreed to examine the CBO position to learn more about the leadership complexities and nuances in relation to future demands of the position. (For more details on the expanding CBO role, see “Skill by Skill,” in the November 2014 Business Officer.) The team also reached consensus to pilot a talent development process for potential successors to the CBO position and measure the impact of the process on CBOs, as well as their successors.

We endeavored to surface issues, challenges, and benefits of designing and beginning to implement a strategic talent management system in the unique higher education environment. Therefore, we developed an “action research study” to understand which talent management strategies would be most effective in the unique ecosystem of public colleges and universities.

This research method involves those who are affected by a problem to collectively and collaboratively engage in solving the problem as well as to bring about change in the organization. One of the benefits of this approach was the ability to improve our understanding of strategic talent management in higher education and share our findings with other higher education institutions and organizations to inform their work in talent management.

Action research methods prompted our team to systematically take action to resolve the problem and reflect on the impact of the action, then make adjustments as we proceeded with the study. Specifically, the action research process involved collecting data; sharing the data with the team and our stakeholders; analyzing the data; planning and implementing solutions; evaluating the solution; and taking further action to resolve the problem. The overarching goals of our study were to:

- Create a culture of leadership excellence throughout the system.

- Develop a program that drives the development of a pool of leaders that is prepared to transition into the role of a CBO.

- Design a process and tools that facilitate communication and integration of internal candidates into the selection process.

- Engage incumbent CBOs in selecting and developing high potential successors.

- Achieve return on investment and decrease external recruitment costs per institution by 33 percent.

- Minimize the costs of external search firms, develop a pipeline of leaders to ensure leadership continuity, and increase retention in the USG.

Elements of Program Design

The team collected data from various sources to construct a comprehensive model of the CBO role. Initial efforts included gathering the following data:

- CBO job descriptions and organization charts from each institutional group in our system (research universities, comprehensive universities, state universities, and state colleges).

- Position description questionnaire data.

- NACUBO’s 2010 Profile of Higher Education Chief Business and Financial Officers.

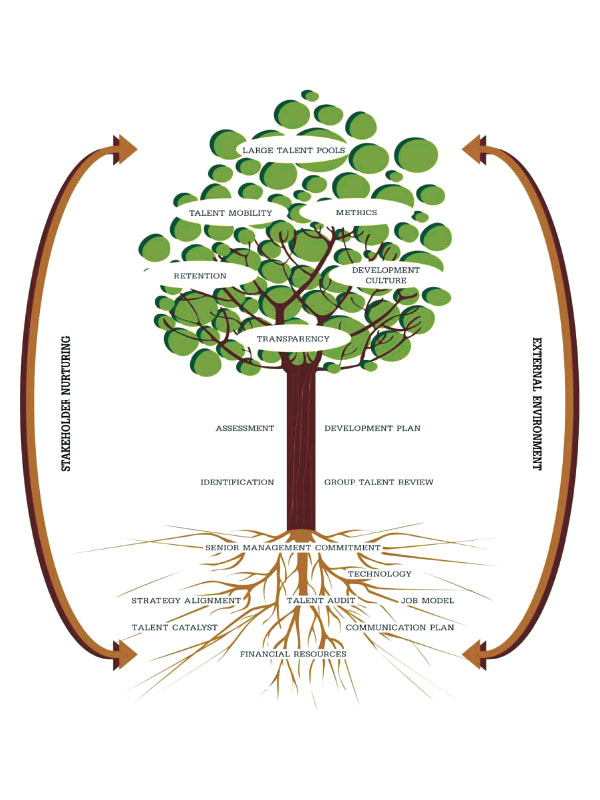

The team also reviewed human resources, succession planning, and talent management literature spanning 20 years. One find was the work of authors Rob Silzer and Ben Dowell. The Talent Stewardship Model, described in their book Strategy-driven Talent Management: A Leadership Imperative (Jossey-Bass, 2009), contains six components of an integrated talent management strategy. These seemingly aligned with our culture and needs: strategy, identification, assessment, development, retention, and talent stewardship.

Using the Talent Stewardship Model as the foundation, the team developed the initial strategy for CBO talent management: (a) design a CBO job model, (b) implement a process to review and identify talent, (c) assess and coach potential successors, (d) develop a talent review database, (e) and facilitate career dialogues and individual development planning.

During the initial team meetings, we conducted a stakeholder analysis and identified critical stakeholders as the chancellor, chief administration officer, vice chancellor for fiscal affairs, vice chancellor for human resources, presidents, chief business officers, and chief human resources officers. One of the primary responsibilities the team identified for these critical stakeholders was to help drive the implementation of the communications strategy to provide timely and updated messaging throughout the development and implementation of the project.

The chancellor distributed the initial announcement via a series of white papers to the presidents of our various colleges and universities. The chief administrative officer distributed memoranda to presidents’ cabinets. Project team members frequently presented project overview, goals, and timelines at internal systemwide conferences and departmental meetings; the project team charter was shared with CHROs, and the chief administration officer distributed project updates to presidents and CBOs regularly.

Crafting a Job Performance Model for CBOs

It was clear that in order to effectively select high-potential talent for the CBO role, we needed a succinct job model that would encapsulate the primary responsibilities and desired competencies of the CBO. We initially planned to use job descriptions to develop a job model; however, we polled the CHROs and learned that CBO job descriptions were either nonexistent or outdated.

After a team member described the job analysis process in progress at her institution, we began considering the benefits of conducting a job analysis for the CBO position. The team found that a legally defensible job analysis is costly, time and labor intensive, and requires a certain level of subject matter expertise and credentials. We then considered the development of a job performance model based on Human Performance Technology theory, as it would assist the team in identifying job factors—such as performance results, competencies, metrics, and optimal work environment—and would produce an overall higher-quality profile of a CBO in behavioral terms to meet the future demands of the role.

- Go to the source. We developed an interview script using a performance consulting template adapted from authors Dana Robinson and James Robinson in Performance Consulting: Moving Beyond Training (Berrett-Koehler Publishers, 1995). We interviewed a sample of CBOs from each of the four institution groups that were in close proximity to the CHRO’s home institution. The CBOs who participated in the interviews averaged 18 years of experience in higher education and seven years in their current positions. Given that the interviews were recorded with the CBOs’ consent, we subsequently transcribed the interviews and provided a copy of the transcript to allow the CBOs to clarify their responses, if desired.

- Do data analysis. We used a useful book chapter that delineated a four-stage process for analyzing qualitative data, using word processing software that we subsequently used to analyze the interview data. We adapted the Performance Consulting Model template to include essential position information from a traditional job description to create a template for our USG Job Performance Model. The team met extensively to review and modify the job model, until we agreed that the model included an accurate synthesis of the position data we collected from various sources.

- Capture and distribute details. After drafting the initial job performance model, we e-mailed copies to the CBOs who participated in the interviews, their presidents, and their chief HR officers to validate the model. We solicited feedback concerning their overall perception of the accuracy of the model, how effectively the model could serve as a developmental tool for CBO successors, ways in which they envisioned using the model, and any suggested changes.

The responses were overwhelmingly positive, and some reviewers provided feedback that the team used to enhance the model and clarify meaning in certain sections. The complete USG CBO Job Performance Model takes up 16 pages, which may be considered lengthy. In an effort to allay potential concerns about the length of the model, we summarized essential information in the first four pages and included detailed supplemental information in an appendix.

The model includes the following sections:

- Purpose.

- Summary.

- Critical performance results.

- Essential duties.

- Knowledge and skills.

- Competencies.

- Environmental factors (supportive and inhibitive).

- Career dimensions (derailers and developmental activities).

- Appendix (competency definitions, best practices, quality criteria, and supporting data).

Identifying and Assessing Internal Talent

The goal of the talent identification and assessment processes is to identify emerging leaders, whose current skills, performance, and leadership potential align with the CBO Job Performance Model. Selected high-performance employees would participate in a talent assessment and other developmental experiences according to their specific learning and development needs.

The USG Talent Review Process, conducted by senior level supervisors, includes five successive steps:

1. eview the CBO Job Performance Model.

2. ssess potential and performance of direct reports and other key talent.

3. alibrate talent pool with institution leaders.

4. otify employees in the key talent pool.

5. onduct a career dialogue with key talent.

While this looked fine on paper, the next challenge the team encountered was to effectively communicate the steps of the talent review process to the incumbent CBOs. We considered a webinar as a way to leverage technology and enable asynchronous learning; however, due to the time requirement and need for clarity of communication, our stakeholders advised the team to meet face-to-face with the CBOs to explain the process and to conduct the initial talent review.

Consequently, we developed a Talent Review Guide, a 15-page primer outlining the steps in the talent review process (see sidebar, “Talent Review Defined” for more details). We forwarded the CBO Job Performance Model and Talent Review Guide to the CBOs with whom we were scheduled to meet to conduct the initial talent reviews. These documents, along with the performance potential assessment, served as the organizing documents for the talent review meetings.

CBO Perceptions of Their Leadership Roles

As mentioned, the CBO position is increasingly complex given the expanded roles and responsibilities that fall under the CBO’s purview. In an effort to depict the essence of the position, the team analyzed (1) CBO job descriptions and organizational charts from each institution sector; (2) results from a position questionnaire each CBO was asked to complete; and (3) data from interviews of 13 incumbent CBOs, which had resulted in 90 pages of transcribed data.

Themes related to CBO responsibilities, competencies, critical performance results, and other position factors became the foundation of the comprehensive job performance model. This model served as the centerpiece of the CBO talent management process.

CBOs were asked during interviews to respond based on their perception of current and future needs of the CBO position concerning institution goals/strategy, environmental factors affecting the position, behaviors that would derail a CBO, critical performance results, competencies, appropriate developmental activities for successors, and effective performance metrics. It is well known that leadership responsibilities in different institution groups vary significantly; therefore, the team was not surprised to learn that CBOs were concerned that attempting to create a single job model that encompasses the position scope for four institution groups would be problematic and beyond the scope of phase one of this initiative.

For this reason, the team designed the model to include general responsibilities relevant to all CBOs and suggested that users adapt it as deemed appropriate to fit the specific needs and conditions of their institution. Overall the CBOs’ perceptions of their leadership roles consist of being a strategist, forecaster, influencer, collaborator, adviser, and operations leader, as portrayed in the CBO Job Model position summary: “The Vice President for Business & Finance serves as the institution’s Chief Business Officer (CBO) and reports to the President. The CBO is responsible for supporting campus operations and the overall management of functions, which may include Accounting, Physical Plant, Human Resources, Student Accounts, Purchasing, Materials Management, Public Safety, Information Technology, Library Services and Auxiliary Services, and Budget. This position is the primary advisor to the President on all fiscal matters relating to the institution and assists the President in the preparation of the annual institution budget.”

Major focus areas for CBOs include communicating and collaborating with multiple diverse internal and external constituency groups to forecast the institution’s needs; then developing multiyear plans to align the institution’s resources (human, facilities, and financial) with goals and initiatives; actively advocating for institutional resources; navigating the political landscape, including increased shared governance; and ensuring excellence in audit performance, rankings, budgets, and certifications.

Critical performance results align with the most important duties reported in NACUBO’s 2013 National Profile of Higher Education Chief Business Officers.

1. Manage institution resources (financial, physical, and human resources) to meet the strategic goals of the institution.

2. Work collaboratively with the president’s cabinet to drive the development and execution of the strategic plan.

3. Attract, develop, support, and retain high-performing talent.

4. Establish and maintain communication for mutual understanding and cooperation with various constituencies.

5. Collaborate with president’s cabinet to promote initiatives that raise the awareness of the institution locally and throughout the state.

Accordingly, USG CBOs may need to give more attention to other needs of CBOs, such as becoming more in tune with the academic and information technology sides of the institution. The critical performance results are listed in the model and in the appendix of the model to include best practices, competency definitions, and supporting information derived from CBO interviews.

CBOs reported that the following environmental factors challenge their goal attainment and job satisfaction:

- Inadequate funding of critical resources.

- Loyalty to an outdated, traditional model of education.

- Limited time and funding for professional development.

- Slow approval processes.

- Campus fragmentation and operating in silos.

Additionally, they reported that CBOs will not be effective in the role if they fail to build relationships with key constituencies, lack deep understanding of the system, lack interpersonal skills, and demonstrate tunnel vision.

Chief business officers, presidents, and chief HR officers who reviewed the draft job performance model unanimously agreed that if future CBOs were developed in accordance with the job performance model, they would be sufficiently prepared to lead effectively in that role.

Overall, the chief business officers viewed the job performance model as a comprehensive, high-quality model that clarified their role within higher education—grounded in rigorous qualitative data that sought to deeply understand the role, responsibilities, and performance required of excellent CBOs in the system.

CBOs Speak Up About Experiences, Successors

We piloted the Talent Review Process with CBOs who volunteered from seven USG institutions. Upon conclusion of the pilot, we interviewed the CBOs and the leaders they identified as potential successors to understand their experiences. Here are some findings:

- The process is thought-provoking and supportive. Overall, the CBOs reported that the process was effective and prompted thoughtful consideration of providing career path opportunities and support for developing future CBOs. One CBO stated, “The process made me think about my staff’s career in a manner to provide opportunities to learn more than the task that they are charged with every day.”

- Morale and relationships are upbeat. Interactions between CBOs and their direct reports were enhanced, as supervisors engaged in candid conversations with their key talent about their strengths and developmental needs. CBOs also reported a high level of excitement among individuals selected to participate in the talent development process. Talent management literature indicates that employee morale increases when talent pools are established.

One USG CBO stated, “I think it’s very helpful from a variety of perspectives. It certainly moves it in a very formal and organized way with things that should be done regardless, which is trying to mentor and bring along those people who are particularly well suited for promotion and for more responsibility and authority. I think it’s really good for the system, university, and individuals in terms of their morale and being considered the up-and-coming leadership.”

- Talent mobility sparks different takes. A few CBOs indicated that they did not want to lose their key talent to other USG institutions. They were concerned that by including their high potentials in a systemwide database of high-potential talent, other institutions would launch recruiting processes targeted at those individuals.

Other CBOs indicated little concern, stating that it would be a disservice to their employees if they did not promote their growth and development even if it resulted in their transfer to another USG institution. One CBO stated, “I will say that is never, ever a worry for me. I believe you should provide the best opportunities for the people who work for you. If they are able to improve their working position in the world, I am 100 percent supportive.”

Key Talent Respond to Training Experience

Overall, leaders identified to participate in the program reported feelings consistent with increased employee engagement. Their feedback concerning the experience conveyed positive emotions and an improved view of the USG as an employer, which ultimately results in increased commitment to the organization and increased confidence in their ability to achieve their career goals. One leader stated, “I was pretty happy. I felt it was kind of an honor to be selected.”

Another leader identified as key talent stated, “It’s extremely reassuring. It sort of renews my commitment to the institution to know that I am thought of in this con-text. This is a significant development opportunity. It took a fair amount of time for my CBO to sit down and work through this with me and I’m honored at that, and that only redoubles my commitment to meet our goals here.”

A key talent pool leader from a state university noted, “It really demonstrated that [the CBO] and the institution are confident in my ability, and that they foresee a future for me in the system. It was really encouraging, and that really impacts my decision in the future—whether I want to continue to stay in the system or look to other options.”

Preliminary Results—Where Do We Go From Here?

This action research study began with a critical review of the current and future state of CBO talent in the USG. This review served to raise the collective awareness of a critical talent gap and prompted leaders to take ownership and provide funding for intentionally developing talent in our system.

Numerous factors affect the total cost of replacing an employee. However, recently the Center for American Progress study (www.americanprogress.org/wp-content/uploads/2012/11/CostofTurnover.pdf) reported the cost to replace an executive is 213 percent of his or her annual salary. Given the average USG CBO salary of $157,000, our estimated savings so far on replacement costs is roughly $334,000.

Other less-quantifiable results are beginning to appear:

- Talent on the move. Upon the completion of phase one of the talent management initiative, a CBO at a USG state college was promoted to CBO at one of our regional universities, creating a vacant CBO position for which there was no heir apparent. The institution’s chief HR officer contacted our office to request access to the talent report for potential CBOs in the system. We recommended a high-potential leader who at the time occupied the assistant vice president of fiscal affairs role. The chief HR officer contacted him and, following a series of interviews, offered him a stretch assignment as CBO. He served as the interim CBO for approximately one year, and then accepted the position full time.

- The word is out. USG presidents and CBOs are beginning to contact our HR office to request names for assistant VP and/or VP of fiscal affairs positions. Recently, a CBO at a state college was promoted to assistant vice president at a research university, saving the USG additional replacement and training expenses. Internal candidates reduce the time to high productivity, because they are already familiar with our culture, policies, and procedures. Institutions may reduce advertising, candidate screening, and certain onboarding costs when hiring an internal candidate. Moreover, internal candidates are, most likely, familiar with other USG CBOs and may already possess the internal social capital to seek assistance with initial problem solving and training associated with the CBO role.

- Patience along the way. Higher education will benefit significantly from a comprehensive shift of the cultural mindset toward talent development. Culture change does not usually occur within a short time span. We recently observed that all final CBO candidates at one of our state universities were external to the USG. Communication of talent management processes and benefits, as well as accessibility of talent pool data, are paramount to effective culture change.

Final Thoughts

Establishing an internal talent pool of future CBOs is certainly a step in the right direction for higher education institutions, considering that 40 percent of externally recruited senior level executives are deemed to fail in their first 18 months, by not performing at the expected level. Studies, including J. Yarnall’s 2011 review of case study literature in Leadership & Organization Development Journal, indicate that strategic talent management can contribute to efficiency and profitability; however, higher education has been historically passive concerning implementing integrated processes to develop and retain talent.

As a Chinese proverb states: “If you want one year of prosperity, grow grain. If you want 10 years of prosperity, grow trees. If you want 100 years of prosperity, grow people.” The University System of Georgia adopted the mantra “Developing the Talent Within,” as we deliberately and proactively identify, develop, and retain leaders to ensure a prosperous future for the system.

TINA WOODARD is assistant vice chancellor for organizational development, and WENDY RUONA, is assistant professor, at the University System of Georgia, Atlanta.