“What happens to a dream deferred? Maybe it just sags like a heavy load. Or does it explode?” These lines from Langston Hughes’ 1951 poem seem appropriate to describe the difficult place in which chief business officers at many institutions find themselves as they begin to take a more strategic approach to addressing deferred maintenance.

Most hope for reasonable progress in addressing facilities—somewhere along the spectrum between “heavy” maintenance on academic and residential spaces and “an explosion” or other serious event, resulting from heating and cooling systems in serious need of repair. For a multitude of reasons, many institutions have deferred for too long their dreams of upgrading, renovating, or replacing campus facilities and space.

According to the State of Facilities in Higher Education: 2015 Benchmarks, Best Practices, and Trends (Sightlines), “The distribution of space across age categories is an important indicator of long-term facilities risk and therefore capital needs. When too much space is concentrated in a specific age category, such as 25 to 50 years old, campuses are challenged to find the money to address the preponderance of needs coming simultaneously.”

Often faced with the choice of having to “catch up” on the 1960s and ‘70s aging space or having to “keep up” with the younger space built since 1995, “there is evidence that campuses overall have achieved a level of success to date on resetting the clock on the oldest buildings.” The report indicates that while 37 percent of the buildings in the analyzed database were constructed more than 50 years ago, only 24 percent of those remain in need of renovation. “Maybe more important,” the survey notes, “is the lack of change in the group of buildings that are 25 to 50 years of age.” … “Samples of work order data … also show that these 25- to 50-year-old buildings drive more and higher cost work orders than any of the other age groups on campus, including the over-50-year-old buildings.” The typical question remains: Is the best strategy to demolish and replace those buildings—or even live without them?

To continue to meet the needs of their major current stakeholders—faculty, staff, students, and alumni—and attract new ones, it’s high time for institutions to make tough decisions like this. Some are just beginning this process, and others are well into it.

Sally Grans Korsh, NACUBO’s director, facilities management and environmental policy, encourages “the understanding that deferred maintenance is a continuous and incremental process that links directly to an institution’s strategic plan. I like to call this ‘responsible deferred maintenance,’ which includes the recognition that there will never be sufficient funds to pay for every single maintenance project, but that smarter practices can stretch budgets much further.”

A number of higher education leaders have taken various approaches to developing such deliberate strategies, becoming more efficient and securing funding in order to address on a planned basis the deferred maintenance on their campuses.

The Downside of Deferring Maintenance

In the past two decades, NACUBO and the Association of Higher Education Facilities Officers (APPA) partnered twice, first in 1988 and again in 1995, on landmark research that initially documented facilities challenges. Research results from the second effort, A Foundation to Uphold: A Study of Facilities Conditions at U.S. College and Universities (1996), showed estimates of $26 billion in accumulated deferred maintenance, of which $5.7 billion constituted urgent needs.

Since that time, the problem has only grown. For example, in a 2013 interview with the American Council of Education, California State University, East Bay, President Leroy M. Morishita estimated that the California State University System had $1.7 billion of deferred maintenance, with $100 million at his campus alone. Other institutions report similar financial backlogs.

According to Cuba Plain, assistant vice president, budget planning and development, for the University of Missouri System (UMS), the facilities needs backlog on its campuses increased from $838 mil-lion during FY10 to $1.4 billion in FY14. “We’ve reached the tipping point, and we have to address this problem,” Plain says.

To better catch up with runaway maintenance and renewal projects, the University of Vermont (UVM), Burlington, established a dedicated maintenance fund during the 1990s to which approximately $7 million is allocated annually. According to Michelle M. Smith, the university’s green building coordinator, the fund was created because the administration recognized the need to allocate specific financial resources to support this critical area.

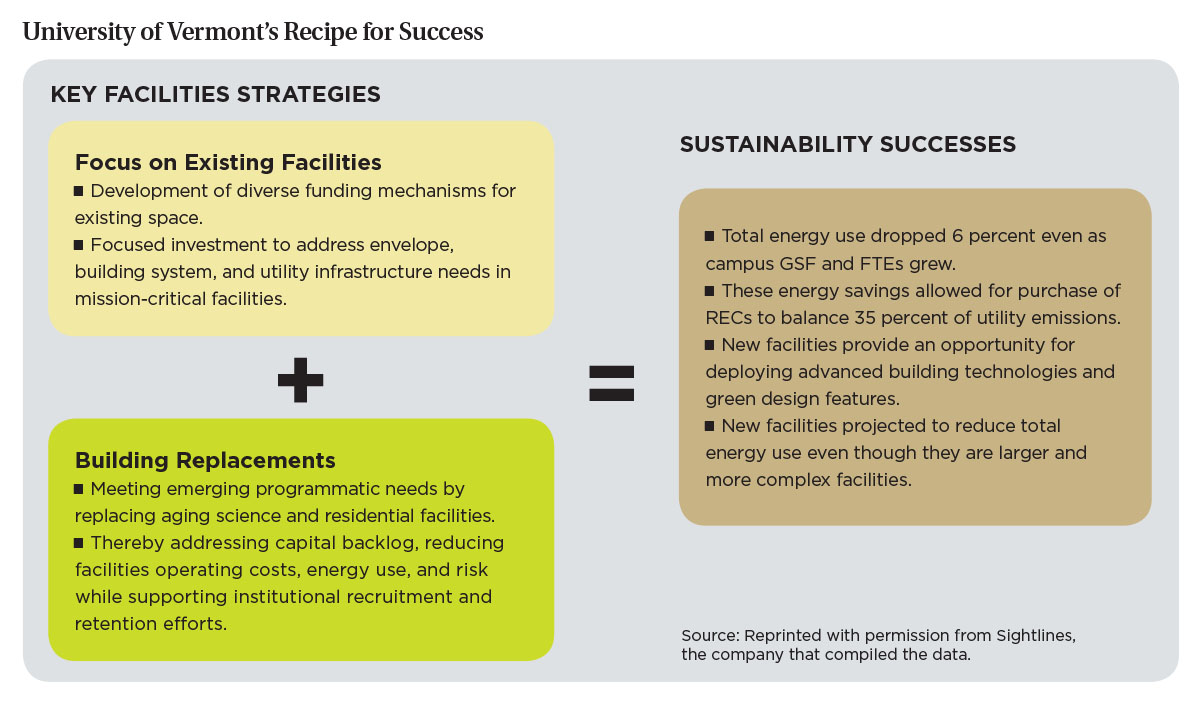

Smith also emphasizes that by focusing on investments that improve the building envelope, HVAC systems, and utility infrastructure the campus has reduced energy costs, even while square footage and student enrollment grew. Improving existing building needs, along with strategic replacement of aging facilities, results in sustainability success.

In the recent NACUBO webcast, Turning Deferred Maintenance Challenges Into Savings, Smith captured UVM’s strategy in an illustrative equation (see figure, University of Vermont’s Recipe for Success); to view the webcast, go to www.nacubo.org and click on the “Distance Learning” tab.

When he arrived at UVM in 2001, physical plant department director Sal Chiarelli lobbied to have some of the needed funds obtained through a bond issue and set aside deferred maintenance. “Everyone wants nice, new shiny things,” he says, “but you’ve got to take care of the old ones as well.” Bond issues have become a part of the overall plan for funding maintenance of the physical plant.

During Chiarelli’s tenure at UVM, the university has revised its perspective on deferred maintenance, adopting what it calls “planned renewal and replacement”—the systematic replacement of building components and systems to extend the facilities’ useful life. This included an annual “Facility Renewal Fund” of $2 million annually, for approximately 20 buildings. This was in addition to the $7 million that Smith identified.

Put Plans in Place

From her vantage point as APPA’s executive vice president, E. Lander Medlin has long held that it’s critical for colleges and universities to implement long-term strategies for managing deferred maintenance. “When we don’t have all the funds that we would like, we have to prioritize,” she says. “Campus leaders must make strategic decisions about which new facilities they are going to bring online and which ones they are going to renovate. It’s true that not all facilities are equal.

“Without having their arms around a long-term strategy,” Medlin notes, “leaders will have to deal with politics on steroids. It’s very difficult politically at nearly any institution to address these issues among stakeholders with strong and differing opinions.”

As far back as 2003, Medlin encouraged institutions to take a more strategic approach to addressing “The Deferred Maintenance Dilemma,” the title of an article she authored for Business Officer. Her advice: “Become much more effective in tying [their] facilities needs and issues to the core strategies and goals of the institution.”

While she believes institutions are doing a better job of this than they did more than a decade ago, Medlin says too many institutions still operate with a run-to-failure mentality: “We run our facilities until they absolutely fail, instead of managing their performance based on established business goals and objectives.”

Although there is no one perfect or preferred approach to managing, refurbishing, or replacing facilities, Medlin suggests that an institution’s guiding values should be the foundation for decision making. “It’s about considering your mission and vision first and foremost, and then developing a strategy based around this key question, ‘How do my buildings and facilities perform, based on these principles?’”

She acknowledges that many CBOs will face “a huge uphill battle” at their institutions, but knows it’s one they must wage to secure a viable future. “I believe in conscious deferred maintenance,” Medlin says. “If I know that I am going to renovate a building within three to four years, I might take more of a duct-tape approach to maintenance. For example, why would I pull up all the carpet now, if I am going to redo the whole building?” she asks. “Deciding to keep the carpet until it’s time to refurbish the building—that’s consciously deferring maintenance.”

Strategies for Reducing the Building Backlog

Whether or not it was a conscious decision on their parts to defer maintenance in the first place, CBOs at institutions of all sizes across the nation are aware, sometimes painfully, that the situation must be contained. Here are some examples of the ways CBOs and other campus officials are taking a more deliberate approach to reducing the number of failing buildings and systems, while factoring in realistic forecasts for maintaining future facilities.

Centralizing campus operations. “We have not had a deferred maintenance strategy until recently,” says Barry Swanson, associate provost for campus operations at the University of Kansas, “but we have one well underway.”

For Swanson, a key element of developing the university’s strategy is looking at current and future needs. “Any new building has to be taken care of from Day One, and we need to put a ceiling on the problems we have now,” he explains. One way the university is better managing existing facilities, is the implementation of processes in which all work orders and project requests are consolidated under the campus operations unit. “This list is reviewed against certain criteria, and some projects won’t get done because they don’t represent a good use of money,” Swanson says. “Before making a commitment, we need to decide what’s appropriate and get the right eyes on projects, before the work proceeds.”

For instance, projects that support research funding will likely get first priority, because they improve the visibility of the university. Coordination and collaboration between and among the departments is very important, notes Swanson. “We are quite aware that our planning process must encompass research, academics, and facilities.”

As part of its process for evaluating multiple priorities, the university has completed approximately 250 system audits to determine what level of maintenance will be required based on the life cycles of buildings. “This will be a continuous process that we’ll probably complete at least every two years to determine our priorities,” Swanson says. “Audits give you a good factual starting point as to where to begin spending your monies. They help turn a nebulous deferred maintenance issue into facts that justify certain investments.”

Developing design standards. “When I came to UCI in 1991, I saw that there was a growing deferred maintenance backlog and also that some of the buildings on campus from the 1980s were already showing signs of the need for major maintenance,” says Wendell Brase, vice chancellor for administrative and business services at the University of California, Irvine.

Based in part on Brase’s observations, the university put in place a set of physical design standards to avoid the need to do major maintenance on any new building for 20 years. “We sought input from all the tradespeople who were facing problems that were surfacing prematurely in relatively new buildings,” Brase says. “From there, we developed the standards and created a quality control unit to apply them to any new construction projects.”

According to Brase, between 1993 and 2013, UCI’s campus has almost doubled in size, making it imperative to build excellent structures with good systems, or what he describes as “the bones of the building.” He says, “In the 1980s the emphasis was less on the life-cycle performance of buildings and more on distinctive design; so the need for major maintenance on those buildings is still growing.

“However, once you have design standards in place, you don’t use them only for new buildings,” he says. “We also apply them to renovations. In particular, when we complete whole-building ‘deep energy efficiency’ retrofits, 10 percent of the investment addresses deferred maintenance problems in mechanical and electrical systems. And those projects save so much energy, the result is that those savings actually pay to fix deferred maintenance problems that had been unfunded.”

Overall, says Brase, “Addressing deferred maintenance is a win-win. It can improve academic spaces, save energy costs, and reduce the institution’s carbon footprint.”

Specifying space management. “We’re in the process of developing a real strategy,” says University of Missouri System’s Plain. “Twenty years ago, the strategy was to set aside recurring budget dollars to handle ongoing repair and maintenance. “However, when hard economic times and changes in administration came along, it ceased to be the most important strategy,” she continues. “It became much more about using whatever funds were left, if any.”

Plain acknowledges that this strategy was not sustainable and contributed to the backlog of deferred maintenance. Moving forward, the university system has turned its attention to more carefully evaluating space utilization.

“We want to examine how we’re using space on campuses, with a goal of reducing net overall space,” Plain explains. “If we have less space to manage, we can do a better job of taking care of it. One way to reduce deferred maintenance is to take a building down. If the level of required repair or refurbishing is significant, it’s better to tear down the existing facility and build another one that will be more efficient to maintain.”

The university opted for objective space utilization studies of all campus buildings. “We wanted a third-party perspective,” Plain says. “From a communications standpoint, it was important to have an arms-length opinion, so that we could be effective in making the case for the benefit and necessity of reducing our overall space footprint.

“We also wanted to communicate with staff, faculty, and students about how much it actually costs to maintain different spaces on campus,” she explains. “People just want more, without understanding how much it costs to maintain space.”

While their approaches vary, all these CBOs agree that the long-term benefits of addressing deferred maintenance outweigh any initial downside of tackling the problem.

“Deferred maintenance impacts the entire university in all its different aspects,” Swanson says. “For instance, by addressing it, you’ll be able to attract and retain students and enhance their academic performance by providing upgraded facilities, which also helps with faculty recruitment. You want to show that you offer competitive facilities.”

Says Plain, “We have to be more efficient and effective and do more with less. We’ve been saying that for 20 years, but now it’s come to fruition. Without space, we are not a research institution. Students and faculty need labs and facilities that are up-to-date. We can’t just go along with business as usual in terms of facilities.”

Funneling Funds to Facilities

There’s no one “formula” for paying the maintenance bills. Funding tends to be quite complex, with institutions tapping into a mix of public and private sources.

- Tax credits. Swanson identified projects on his campus that qualified for tax credits that were then sold to generate funds. “We have two historic districts on campus, and any work we do in those areas is eligible for tax credits that we can sell on the open market for 90 cents on the dollar,” he says. He estimates that the sale of tax credits will generate between $1 million and $2 million.

Others sources of annual funding include the state of Kansas’ education building fund ($9 million), the university’s infrastructure fund ($2 million), and donor funds.

- Dedicated budgets. “There is never enough money for strategic maintenance renewal and mitigation,” UVM’s Chiarelli says. “You have to look at the master plan and try to fit in what you can, based on limited funds.” The university has an estimated $3 million to $4 million to spend, which is only about 25 percent of what’s needed to address maintenance issues in the older buildings on campus.

Chiarelli also notes that maintenance and repair applies not only to the central plant but to all “the other stuff that’s not attached to a building—and that people are less interested in funding. I look at the campus as my big house,” he says, “and others on campus are trying to tap into my budget. You have to stay on task in managing the available financial resources.”

Fortunately, the university created a facilities renewal fund in the early 1990s, which requires that 1 percent of construction costs are set aside for renewal and renovation, to help ensure that funds would be available for maintaining newer facilities, as they were constructed. “The fund was created because administration knew that the pool of funds available might not be enough to address ongoing needs,” Smith says. “Of the more than 300 buildings on UVM’s campus, 20 have facilities renewal funds (totaling $2 million annually) and, therefore, will add to deferred maintenance costs much less quickly than will existing facilities without such funds.”

- A mix of resources. For her part, Plain also recognizes that a variety of funding sources will be needed to fully address the ongoing upkeep of UMS’s campuses and its other facilities, which include a hospital and several clinics. Internally, to help contain and better manage deferred maintenance costs, UMS revised its facilities needs funding and reporting policy in 2012. Each campus is to follow “an industry best practice [requiring] an annual investment that supports the maintenance of a Facilities Condition Needs Index (FCNI) of .30 or lower.” FCNI is the sum of the total cost of capital renewal, deferred maintenance, and plant adaptation divided by the estimated cost of replacing the buildings.

Externally, while the overall level of state appropriations has declined over time, UMS has been effective in advocating for additional funds. “We recently completed a state bond issue,” Plain says, “that included a $200 million funding package financed over 15 years, with $95 million specifically appropriated for maintenance and repair. The state legislature also passed a 50-50 program, in which private gifts will be matched against state funds. To date, $28.6 million in general state funds were appropriated and leveraged against $29.7 million in private gifts, to build four academic buildings.

“We know that the state can’t solve our problem, but we need them to be a partner,” Plain says. “Donors won’t solve our problem either, but they have to be a component. We realize that we are not going to receive a massive infusion of funds to address this problem. We have to bail ourselves out; and I think we can do it, but it’s not going to be easy or painless.”

APRYL MOTLEY, Columbia, Md., covers higher education business issues for Business Officer.