![]()

![]()

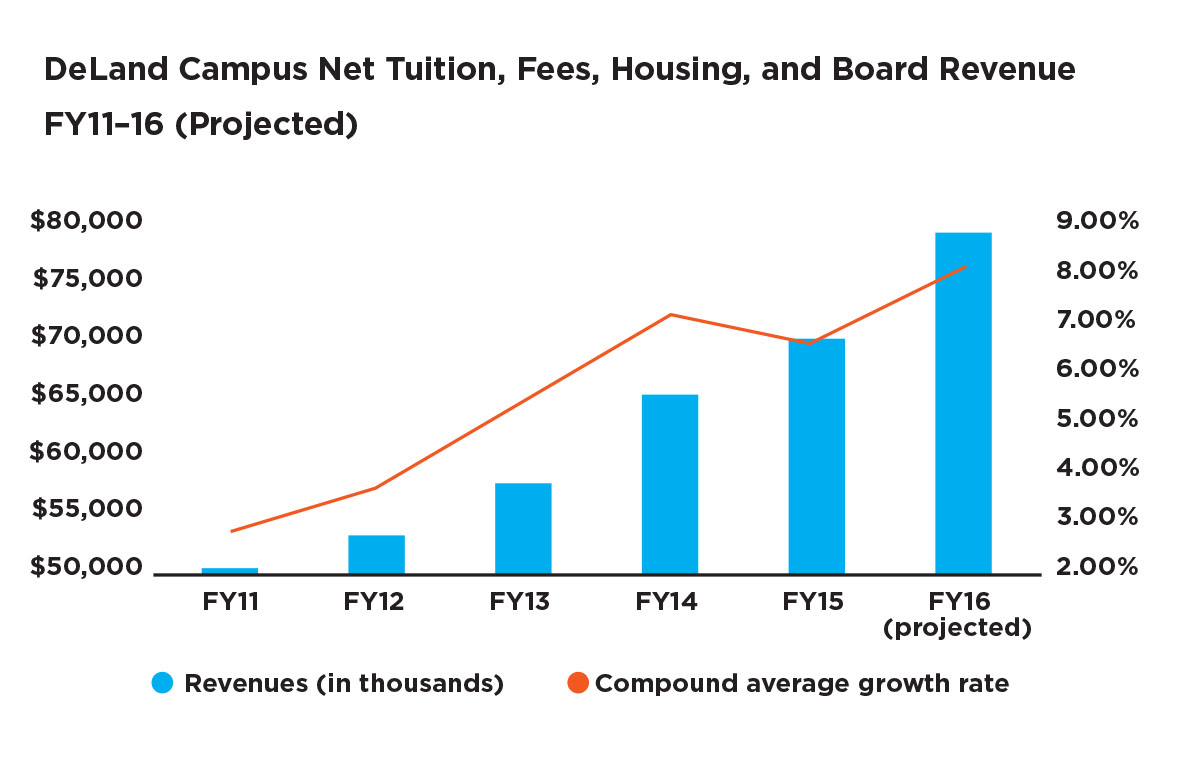

In 2011, after several years of enrollment declines at Stetson University, Deland, Fla., student net revenue generated from tuition, fees, housing, and board failed to provide sufficient operating resources to support budget needs. Only 80 percent of the 2,600 undergraduate capacity was utilized. Five years later, net revenue generated from undergraduate enrollment—Stetson’s largest revenue stream—has skyrocketed.

This growth has provided Stetson’s undergraduate campus with the operating resources to:

- Increase faculty compensation from the 10th percentile to within 3 percent of achieving median.

- Improve staff compensation to achieve local, regional, and national benchmarks.

- Add approximately 40 new faculty lines.

- Fund an annual $5.6 million renewal and replacement reserve (2 percent of building replacement cost) by FY15–16.

This did not occur serendipitously. Strategic planning is a necessary exercise to maximize institutional progress, but without execution it can be a waste of time. A strategic plan needs to be communicated so that the entire institution can be on the same page, working individually and collectively to achieve defined goals.

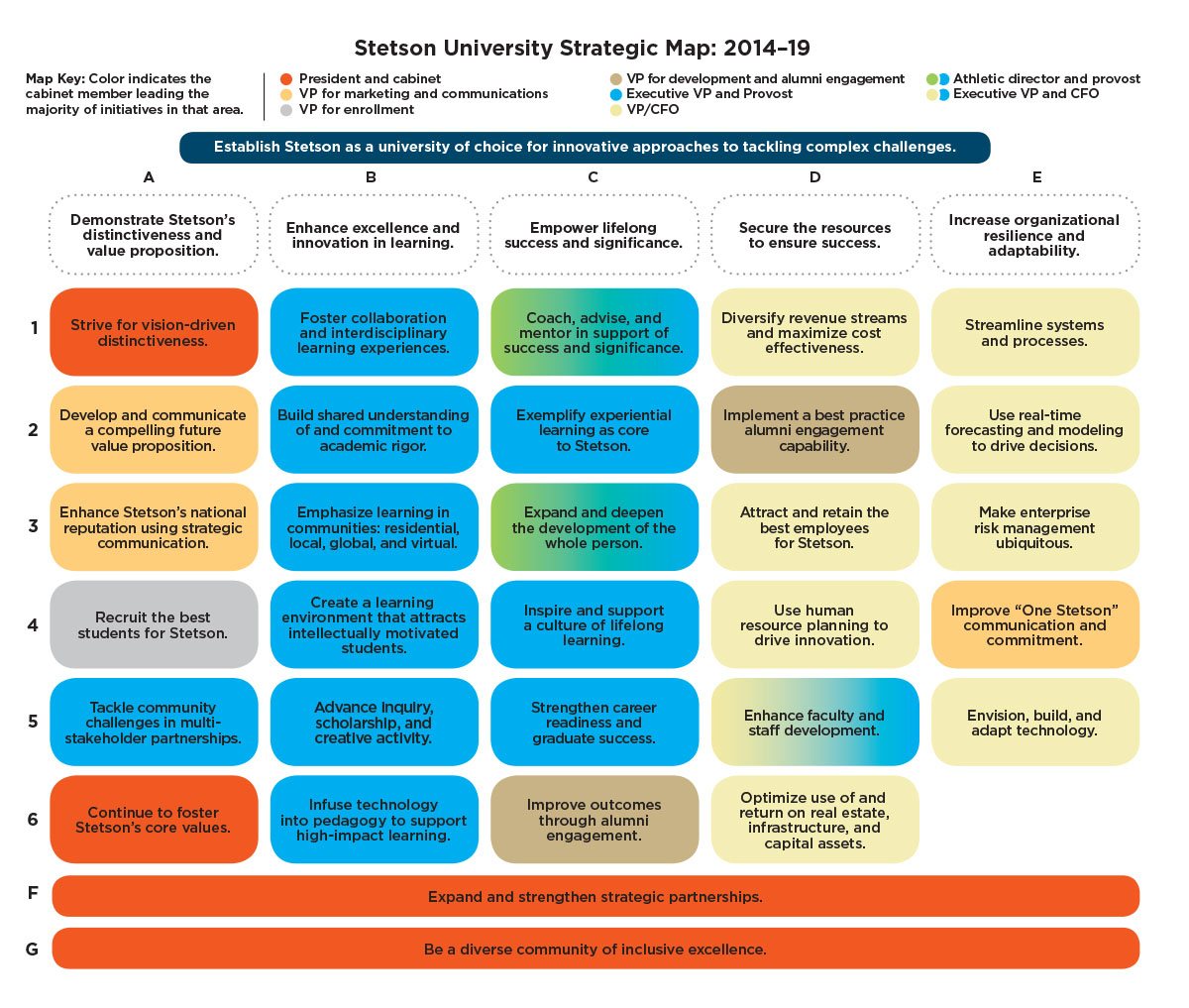

At Stetson University, we threw out the book and reduced the strategic plan to a single page—what we call the strategic map. It cannot comfortably stand on a shelf, but works rather well taped to a wall or a desk where it is seen daily, referenced often for ad hoc decision making, and readily available to guide annual budget planning. Budget administrators know that initiatives must relate to the plan and help accomplish a strategic goal to survive the prioritization process for limited resources.

The First Plan and Map

Wendy B. Libby became Stetson’s ninth president in 2009 and immediately recognized the need for an action-oriented strategic plan as well as an overall culture of planning. With fall 2009 undergraduate enrollment at 2,100 students on Stetson’s campus—500 under capacity—she needed to make a decision: either grow enrollment or reduce capacity.

At that point, Libby notes, Stetson’s overall strategy “was to begin to become strategic in how we made choices and not let the environment force us into things or surprise us; as best as we could, we were determined to avoid surprises.” She created five “quick turnaround” committees for the undergraduate program at the DeLand campus. Chaired by faculty members, these committees evaluated areas such as enrollment, student life, facilities, and athletics.

When the committees issued their reports and recommendations several months later, significant changes began to take shape. The biggest decision was to not only fill Stetson’s existing capacity, but to increase the undergraduate enrollment to 3,000 by fall 2016. This number of students could potentially provide Stetson with the resources needed to improve the market position of compensation; add new faculty for greater interdisciplinary breadth; and significantly reduce deferred maintenance.

But the questions centered on how and what: How could Stetson do this, especially in an anemic economy where other private liberal arts institutions were struggling to maintain enrollment and even keep the lights on? What process and communication tools would keep the plan simple, alive, and engaging?

After identifying the direction to grow, groups met to build Stetson’s first strategic map with the guidance of Tim Fallon, president of TSI Consulting Partners Inc. The three-year map (2011–14) was organized around a central guiding challenge to “focus innovation to drive Stetson from success to significance” and rested on two foundational goals: increasing financial health and sustainability, and deepening the way Stetson’s core values are lived out. Six overall (or “uber”) goals were identified, including: increase the excellence of the academic program; renew and build critical systems and infrastructure; and be a great place to work. In turn, five or six directional goals supported each uber goal, to help identify achievement mileposts along the way.

Helping Set Priorities

Stetson’s strategic map prioritized several goals for attention in the first year by highlighting them in color. “Uber” leaders—vice presidents and deans—were assigned the foundational and overall goals, and they worked with faculty and/or staff in their areas to develop the directional goals through initiatives. This helped the plan benefit from the early identification of low-hanging fruit.

Supporting only new initiatives that aligned with the strategic plan and were prioritized against other proposals sent an important message and reinforced the culture of planning. Regular reporting to the board through budgets, status reports, and progress reports helped the community stay focused. For example, reports such as the Enterprise Risk Management dashboard not only included risks and mitigants, but also associated them with the appropriate strategic goals.

Unlike many strategic planning processes, less time was spent upfront with detailed planning by a core group of administrators, in favor of sharing the one-page map with the community to enable, drive, and support progress.

Fallon observes that condensing a strategic map to a single page offers the benefits of:

- Forcing the planning team to focus on the most viable and important opportunities and outcomes, which keeps the plan from becoming too aspirational and outstripping resources.

- Requiring the planning team to narrow down hundreds of comments, suggestions, and documents into an actual strategy.

- Providing a powerful visual tool for communicating the strategy across many different constituencies.

- Having the ability to be easily updated to reflect progress made, obstacles encountered, and changes in both the university and the wider world.

The Next Iteration

With the success of the first strategic plan well underway and a fundraising campaign forming, the next round of strategic planning started in fall 2013. This iteration was much more encompassing than the first and had the added benefit of strengthening connections with current donors and creating relationships with future donors.

We began with a series of four open discussions, during which we invited the Stetson community—faculty, staff, students, trustees, alumni, and friends—to examine major trends in higher education and assess the opportunities ahead. These discussions coincided with focus groups and an online survey that gathered feedback on the university’s strengths, critical issues, and key priorities.

Drawing on all this information, a vision team and a mapping team produced guiding documents to be vetted with the university community and further refined by feedback. Given the success of the first map in making strategic goals ubiquitous, creating a new map for the new plan was an easy decision. Other than a subtle change to color-code the campus leaders responsible for particular initiatives, the one-page format has remained essentially the same.

The 2014–19 strategic map was approved by Stetson’s board of trustees in May 2014 and reflects a new central organizing challenge to “establish Stetson as a university of choice for innovative approaches to tackling complex challenges.” It also includes new foundational and directional goals to keep the institution on the road to continued strategic success.

BOB HUTH is executive vice president of finance and chief financial officer, Stetson University, DeLand, Fla.

SMALL INSTITUTIONS: